Last year, in May, the remarkable (truly without equal) Herbie Hancock gave the commencement address at Soka University, where I teach humanities and literature, as well as coordinating the "Jazz Monsters" concert series which I founded in 2005 after decades of teaching at Cornell, Brown, Stanford, Brandeis, and UCLA. Herbie's eloquent message to our graduating seniors was one-for-the-ages. Those who know his music, across his continually rising artistic career, know that his musical imagination and lyrical execution are deep and generous. To experience Herbie Hancock—the astonishingly gifted pianist and composer, as well as the peerless band leader and musical visionary—is to encounter the professional brilliance of an utterly unique and path-breaking musician. That, in itself, is a blessing. Of the musicians in his generation, none have attained his ongoing and lasting distinction.

But that experience and its enjoyable witness to Herbie's seemingly bottomless energy and talent cannot fully comprehend this man's innate educational and spiritual commitment. Many musicians who've adored Herbie Hancock over the years have spoken to me about his special qualities. John Hicks, my longest lasting, oldest friend from our mid-teens growing up in St. Louis, often told me of his abiding respect for his hero's illumination: "the strong vibe" of inner rightness, as John saw it. Until I met Herbie Hancock myself, and spent nearly ten hours in his company at his Los Angeles home, I could never intuit how thoroughly accurate John's insight genuinely was. The occasion for my visit several years ago was to audition recordings that I'd made of Herbie and his dear friend, Wayne Shorter. Adrian Butts, a talented speaker designer from Canada, asked the Maestro for permission to include me in his visit to adjust a set of expensive Tetra speakers at the heart of an excellent stereo system. The time we shared together was nothing short of a revelation that, to this moment, remains outside the boundaries of anything I've experienced before or after.

That statement sounds extreme, perhaps idealistic and misguided. It's not. My hours listening with and talking to Herbie Hancock can be thought of as effortless time with a brilliant companion whose warm hospitality was both gregarious and cheerful. However, something more extraordinary was underway. In seven-plus decades of life, I've spent many hours with exceptional friends and colleagues: Carl Sagan, William Arrowsmith, Arnold Toynbee, Albert Murray, Clifford Geertz, R. P. Blackmur, Benny Golson, Max Roach, Sarah Vaughan, A. R. Ammons, John Ashbery, Robert Creeley, Art Farmer, Red Rodney, Sweets Edison, Hank Jones, Stan Getz, Buddy Rich, Bob Florence, Joe Henderson, Red Schoendienst, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, I. O. Wade, Cecil Hannan, Max Black, Neil Hertz, R. O. Muether... a life rummaging across inspiration and wisdom. To spend focused hours in Herbie Hancock's company is to find yourself unknowingly lifted incrementally to a high interior place.

I realize that such testimony tugs at credulity, but such elevation as I experienced its accompaniment to my time with this one-of-a-kind man is precisely what occurred—so insouciant in its mysterious partnership as I left, escorted to Herbie's gate with an invitation to return, that I called my wife as I drove home to report that, with nothing but water as our day's libation, I felt stoned (spiritually boosted) without prosthetic aid or supplement. In truth, I can't explain the ineradicable uniqueness of all that except to assert (enigmatically, no doubt) that the subjective vividness of my experience was not illusory but a kind of contact high that one takes from proximity with a shaman or guru. That understanding, in turn, was given objective reinforcement last year, May 2013, when the Maestro brought the whole of his enthusiastic mentorship to one hundred-plus Soka graduates. I saw, from my seat on the stage, Herbie's magic touch upon others, gently, directly.

My bet is that Herbie has very little awareness or self-conscious concern for this apparently incidental influence that he bears with him as he tours the globe. But, in this old guy's congenitally skeptical outlook, the special man who will again grace the Jimmy Lyons Stage at Monterey this year, is no casual accomplice to the 57th iteration of the world's greatest jazz weekend. He is a beautifully abnormal and, thereby, iconoclastic example of that rare occurrence in the arts (presaged in the last century by those at their peak such as Duke Ellington and John Gielgud, Willie Mays, and Picasso) when sublime creative talent arrives at its mature fulfillment. This is a moment in jazz history when our too frequently renewed sense of loss for the disappearance of men and women who advanced and nurtured this great tradition deserves the affirmation of embracing its most profound iconic inheritors. For no other reason, a trip to the Monterey Fairground this year is authorized concretely by Herbie Hancock's welcome genius.

Several years ago I had enormous fun recording a mind-boggling trio, co-led by Christian Mc Bride and Geoffrey Keezer with Tereon Gully's spectacular percussion work. I've heard a lot of music. That trio accomplished things I've never encountered before or since. Christian and Geoffrey will be on hand this year. Grab your place for their sets early.

One of my all-time favorite musicians is the remarkable saxophonist-flutist Charles lloyd. Nine years ago Charles returned to the scene of his legendary 1966 festival concert to reprise that now immortal recorded performance, "Forest Flower: Sunrise, Sunset," with Jack de Johnette and Keith Jarrett. I was torn, in the days before that took place, by equal inclinations toward eager interest and wary concern. There was no reason for my concern. That 2005 performance was the equal of, perhaps in some way superior to, the original concert. Charles is well known for his deep sense of privacy. He is no less well-regarded for his intense dedication to what might be thought of as artistic perfection, but what I suspect is more akin to an ethic of utter energetic and aesthetic spiritual abandon. We're lucky to have another chance to be regaled by his evanescent power and delicacy.

A pianist who I look upon as subtle and surprising first, last and always is Billy Childs who rewards his listeners with his ability to find fresh harmonic and emotional registers. He has slowly become not so much an "elder" as, nonetheless, a sort of unofficial jazz statesman.

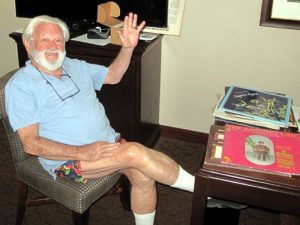

Finally, and I guess this truly may be a finale after so many long years (since the beginning at Monterey, in fact), Earl Newman, the pixie-like whirling artistic dervish whose posters and calendars each year reflect Monterey's headline musicians, is preparing to bid adieu to his fans and followers, giving up his prominent station outside the back of the Jimmy Lyons Stage. My dear pal and longstanding colleague, photographer-extraordinaire Michael Oletta, introduced me to Earl more than twenty years ago on my initial visit to Monterey. They are of like minds and outlooks: two visual craftsmen who seek startling images with lasting value—Michael by use of his ever ready Nikon and Earl with his indefatigable year-round work to bring strong graphic imagery that memorializes each year's endeavor. Although it's inevitable that we all move forward (think here of Spencer's Mutability Cantos; Ovid's Metamorphoses; Samuel Beckett's eternally about-to-check-out anti-heroes), some people have a greater, more tenacious hold on perennial expectations. In his genuinely quiet way, Earl is one of those. I know that I'll miss him on future jaunts to Cal Tjader's and Dizzy Gillespie's former romping ground. I'm certain many others will find Monterey, by his absence, less cheerful because no longer defined by his calm dignity, colorful imagery and the perpetually expectant, self-created innocent character who—merely being himself, like Charlie Chaplin's heroic silent figures—embodies a One-Man Carnival of noble delight.

[Images by Michael Oletta]