Schumann, Symphonies 1-4. "Giuseppe Verdi" Theatre Orchestra, Trieste/Julian Kovatchev. Erresse RS 6367-72/73 (2 CDs). Timings: 75.54, 69.45

Dvorak, Symphonies 4-6. "Giuseppe Verdi" Theatre Orchestra, Trieste/Julian Kovatchev. RS 053-0134 (3 CDs). Timings: 40.59. 38.17, 46.33

The success of Naxos, circa 1990, showed that there was a market for newly recorded low-priced classical CDs. The result, as CD manufacturing ramped up to meet the demand, was a burgeoning of companies seeking to cater to it, producing a veritable flood of such records.

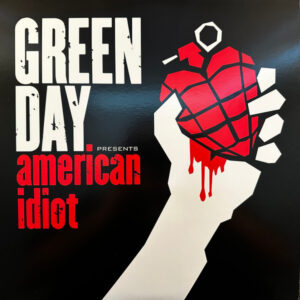

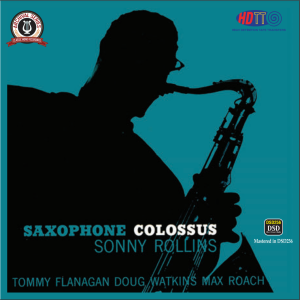

These two albums, appearing five years apart, represent one such strain, from a little-known Italian firm called "Real Sound"—though you only learn that in the fine print—hence "RS." ("Erresse," on the earlier release, is simply the Italian pronunciation thereof.) The artwork for most RS issues conforms to the template in the photos, with a solid background, a dominating photograph, and identifying text; most releases were tagged at midprice. The Bulgarian conductor, Julian Kovatchev, died in late 2023; the OperaWire obituary claims he was sixty-three, though he was born in 1955. (It's the New Math again….) The orchestra is based, not in a major arts center, but in Trieste, best known as an Adriatic "hot potato" between the World Wars.

The Schumann set, issued in 1995, isn't—well—bad, but let's just say everyone involved was experiencing growing pains. The slow introduction to the Spring (No. 1) is perhaps half the normal tempo, almost falling into individual notes. (If this'd been vinyl, I'd have checked the turntable speed.) I could have accepted this as a perverse sort of one-off, but exaggeratedly slow tempi constitute Kovatchev's besetting sin throughout the set.

The Second's slow introduction also crawls; the Adagio espressivo is too adagio to be espressivo. In the Fourth—arguably the strongest "symphonic" construction—the outer paragraphs of the Romanze simply droop, though much of what's in between approaches a more or less normal tempo. The Rhenish (No. 3) gets an extroverted, mostly straightforward performance, but, in the Ländler-Scherzo's home stretch, the conductor imposes unmarked tenutos on the horn proclamations. I assume Kovatchev was trying to prove something, but I'm not sure what.

Neither is the orchestra exactly a smoothly oiled machine here. In particular, running eighth-notes in the woodwinds or the interior strings turn skittish and push ahead. (The first violins, to their credit, maintain their equilibrium even in the long, unfurling runs of the Second's finale.) Perhaps the players were nervous, or perhaps Kovatchev's beat was unclear—or, perhaps, an unclear beat made the players nervous. In any case, the results are untidy.

The Dvořák box is also part of a complete cycle, issued in 2000 as three 3-CD sets. This sounds logical, but comes out less so. For starters, where RS fits the Schumann symphonies compactly onto two CDs, each of Dvořák's slightly longer ones gets a disc of its own, with no fillers. This avoids annoying disc breaks, but, even at midprice, it's uneconomical. Also, the scores offered here—the middle three of the composer's nine—constitute strange bedfellows, as a glance at the opus numbers will attest. The Fourth Symphony, an early work, gained canonical acceptance relatively late; the other two reflect the composer's fully mature style.

Still, the conductor seems to have made good use of the intervening five years. Kovatchev "gets" the quirks of the Fourth: the ambivalent lyricism of the Andante sostenuto‘s wind chorale—surely Tannhäuser was in the composer's ear—and the Scherzo's joyous "surprise" second-theme recap. And the Finale‘s obsessively repetitive opening motif—it really becomes a bit much—ultimately underpins the glorious final recap.

Wikipedia calls the Fifth "largely pastoral in style," and the chirping, duetting clarinets at the start certainly suggest as much; the Finale tends to ramble, but there Kovatchev has plenty of illustrious company. The Brahmsian Sixth also maintains an intermittently pastoral feeling; in the first movement's tuttis, it's nice to be able hear the whooping horns, buried in some of the higher-profile versions.

And the playing? The woozy, uncertain finger-tremolos that open the Fourth don't augur well; but, in fact, at the compact tutti, ensemble clears up immediately. The Sixth's active Furiant, sporting hemiolas (hemiolae?) to boot, is similarly insecure in a few spots. But, overall, the playing is much better than in the Schumann—clearly, the orchestra has "settled in" nicely. The well-focused ensemble sound and mostly clear balances carry the listener along—in the Fifth, I frequently stopped "observing" and just listened. A sonority that's slightly lighter than usual actually seems to help clarify Dvořák's rather busy developments.

It's odd that the CD boom should already be provoking nostalgia—and these recordings and their companions fulfill, at least in a minor way, the "documentary imperative." (The obligation to preserve artists' work for posterity was once treated as Holy Writ.) Whether you need to hear them, beyond their sheer curiosity value, is up to you—both sets are streaming on Amazon.

stevedisque.wordpress.com/blog