Handel: Concerti Grossi, Op. 6 and Op. 3, Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin. Pentatone (Three Albums 2019, 2020 (DXD) [HERE]

This is big, bold, exciting Handel. None of your timid tinkly stuff. This music has drive! It has bass! It is energetic! Just have fun with it.

Yes, that was my first reaction listening to this new recording of Handel's Concerti Grossi, Op. 3, performed by the Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin. Part of the reason for my reaction is the recording (more about which later), but most of the reason is the playing by the members of the Akademie, or "Akamus" as they are commonly known. They drive forward with vigor under the direction of concertmaster Georg Kallweit.

With this introduction, I next had to go find Akamus' recordings of the Opus 6, available on two albums as Part 1 and Part 2. In these three albums, Pentatone and Akamus have created a delightful trilogy, all of which are available in DSD256 and DXD downloads from NativeDSD.

This music by Handel has been an important part of my musical life for as long as I can remember. For decades my go to performances were the classic Trevor Pinnock recordings with The English Concert on Archiv (1982, 1984) and the Neville Marriner performances with the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields on Argo and L'Oiseau Lyre (1964, 1968). The Marriner performances are with modern instruments played with a nod to historical practice. Both the Pinnock and Marriner continue to be wonderful performances and recordings.

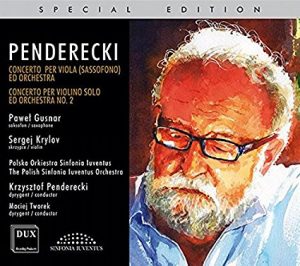

Cover photos courtesy of the labels and Discogs

But today I have a new personal standard for these works: the performances by the Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin recently released on Pentatone. With each additional listen, I find new rewards. Akamus reigns!

These performances are light, agile and energetic—and here I refer to all three recordings. These are historically informed performance (HIP), but without being extreme. Tempi are flexible, there's some moderate vibrato, but most importantly there is excitement and some adventurousness in the playing. These are musicians well versed in the playing style of the period, completely comfortable in the genre. And they give the music some lift that I find most engaging. But they still play it pretty straight—this is not avant garde Baroque.

Across all of this I am struck by the superb precision with which the ensemble plays. And did I say "ensemble?" Oh, yes, the ensemble playing it as tight and together as one might possibly wish to hear.

Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin (photo by Uwe Arens, courtesy Akamus)

The Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin was founded in 1982 in what was then East Berlin. With thirty core musicians, frequent guest conductors, and a hundred concerts a year, they’ve long been one of the better known period instrument groups. They perform under the leadership of their four concertmasters Midori Seiler, Stephan Mai, Bernhard Forck and Georg Kallweit, or guest conductors like René Jacobs with whom they have a deep and abiding relationship. In this trilogy of Concerti Grossi, the two albums of the Op. 6 are led by Forck and the Op. 3 by Kallweit.

All three albums were recorded at the Nikodemuskirche, Berlin in May 2019 and released separately in 2019 and 2020. The Nikodemuskirche is a frequent recording venue in Berlin with, I'm told, a very nice acoustic space for music recording.

Kulturkirche-Nikodemus Berlin showing coffered wooden ceiling and organ niche (photo by Bodo Kubrak, Creative Commons)

Kulturkirche-Nikodemus Berlin exterior (photo by Bodo Kubrak, Creative Commons)

In these fairly closely miked recordings, that natural acoustic environment that I greatly value is not so readily apparent. There is nice bloom to the sound of the instruments, but just not much sound of the hall. Nonetheless, this choice to record fairly closely pays off in the warmth, richness, and detail that we hear in the timbre of the instruments. The sound is more like we are listening as fellow members of ensemble, not as the audience—an artistic choice by producers and recording engineer. As Ann says, it is intimate music listening.

The positive tradeoff from the miking chosen is a more focused and detailed instrumental sound. Every instrument is heard, every detail of the playing of those instruments is heard. The strings have great bite and resonance, the winds are articulate, and the lute actually sounds!

I suspect it is this positive tradeoff to the miking that contributed to my initial reaction when first listening to the Opus 3 recording. With the closer miking, the resonance from the strings of the viola da gamba and double bass truly hold sway, giving the entirety an impact that one does not frequently hear in period instrument performances.

But please don't misread what I'm trying to say here. This is not "ram it down the throat of the instrument" close miking. This is more a matter of each instruments being captured and separate tracked so that the whole could be re-blending in the post production mix and each instrument delicately pulled out in the balance. Nothing heavy-handed going on. As Tom Caulfield observes, the recording engineering and post production mastering is "...ultimately a decision the producer is making to achieve a desired objective. It is, after all, a piece of art."

Recording session for the Op. 6 with concertmaster Bernhard Forck from the YouTube video posted by Pentatone. In this 2 minute video there are additional views of this session and an interesting conversation with Forck. (by permission Akamus)

Recording session for the Op. 3 with concertmaster Georg Kallweit, same venue, same dates. I always wonder what the musicians are listening for when I see such concentration around the session playback speakers. (courtesy Akamus)

The 12 Concerti Grossi of Opus 6 were written by Handel in a single month in 1739. They illustrate as well as any of his other compositions the incredible inventiveness of his musical talent. As I was listening to music by another composer (whose name shall not be mentioned), I commented to Ann that there clearly are reasons some composers' works are not as frequently played as Handel's. Her reply was simply, "Not everyone can be a genius."

So true, and how fortunate are we to still live with Handel's music 261 years after his death in 1769.

The Opus 6 Concerti are exceptionally varied, and they speak with the musical voice of many influences and a range of textures. One hears nods to Corelli and Scarlatti, and re-cycles from his own music. One hears overtures, dances, fugues, airs, variations, and trios. Handel wrote these for playing during performances of his oratorios. They were intended as interludes, not independent works—and certainly not as concertos as we know that term today. But, it is as independent works that we've come to know them.

Unlike the Opus 6, the Opus 3 Concerti were most likely assembled by Handel's publisher rather than by Handel himself. And, they do demonstrate somewhat greater variance among the different works. Yet it is this greater variance perhaps that draws me more to the Opus 3 set when I choose some music to enjoy for an hour. If you are familiar with Handel's Water Music and expecting something as stylistically and thematically coherent, you'll either be disappointed or very pleasantly surprised. These are all much more bits and bobs musically. And in that lies their charm for me.

So, here are presented three albums of Concerti Grossi—which to choose if you want to sample just one? My recommendation is the Opus 3 with Georg Kallweit as concertmaster. The playing by Akamus is as refined and polished on all three albums, so nothing to select from there. But the music in Opus 3 is, to my mind, just a bit more adventuresome and diverse for a first go into this music. And, the opening movement of Opus 3, No. 1, is a high energy romp with Kallweit leading. Ann says she finds it hard to catch her breath with everything driving ahead so furiously fast, and I agree.

It's also exhilarating!