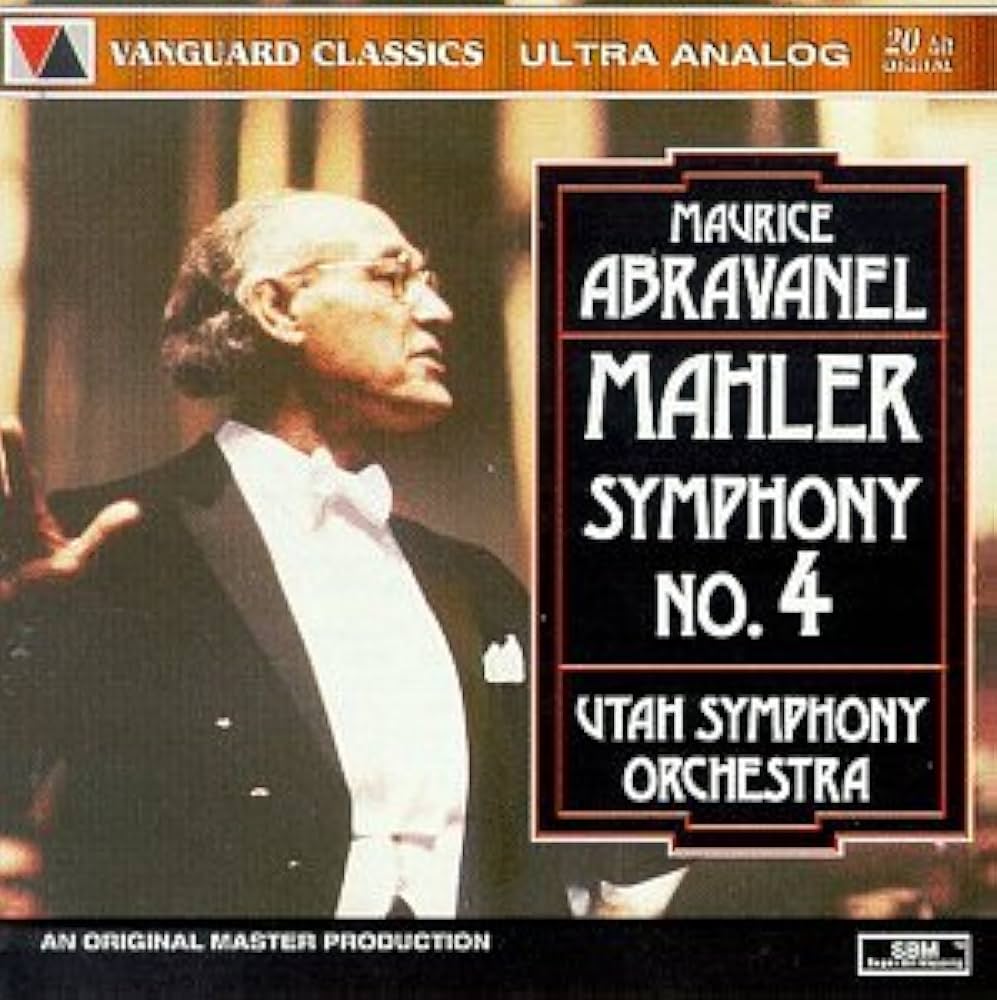

Gershwin, Rhapsody in Blue*; An American in Paris; Cuban Overture. Ivan Davis, piano*; Cleveland Orchestra/Lorin Maazel.

Copland, Appalachian Spring; Fanfare for the Common Man. Los Angeles Philharmonic/Zubin Mehta. London Jubilee 417 716-2. TT: 71.17

For me, as a professional musician and a professional listener, life doesn't always allow much time for repeat listening. But I find it instructive to revisit this or that older item as I can—the shift in my reactions can be instructive. Since I'd heard, and enjoyed, the vinyl releases of these Decca/London performances, I was curious to revisit them.

Lorin Maazel's Gershwin isn't as unlikely as you might think: that august, sometimes arrogant maestro led the first complete, authentic recording of Porgy and Bess, after all. I remember being impressed, long ago, both by these performances and by their vivid, souped-up engineering—though, pressed for particulars, only the crisp woodblock near the start of the Cuban Overture would come immediately to mind.

The big, plush sounds of the Cleveland Orchestra, with intensely vibrant strings and big-boned lower brass, are exceptionally high-octane for this music—the traditional "favorite sons," Bernstein and Fiedler, favored lighter textures and greater rhythmic snap. The "deep" sound brings a change of emphasis: if the Rhapsody is usually symphonic jazz, here it's symphonic jazz. Mr. Maazel's interpretation is mostly good, occasionally eliciting the odd buried detail, though he had a penchant for attention-drawing affectations: the famous clarinet glissando is absurdly drawn-out, and the passage after the first tutti goes at a bracing clip, simply because, with this orchestra, it can.

The surprise is pianist Ivan Davis. His Phase Four recordings of concerti by Rachmaninov, Tchaikovsky, and Liszt suggested a "power" pianist. Here, we get the power, as expected, but I was startled at the numerous quieter, more introspective inflections, even within some of the flashy cadenzas, and nicely complementing Maazel's expansive treatment of the "big tune." And his articulation! You rarely hear Gershwin's figurations projected with such a limpid tone and lapidary finesse. It's a revelation.

Maazel finds the reflective moments in An American in Paris, too—the English-horn episode is almost desolate—as well as an almost Debussyan emotional ambiguity (no surprise from so fine a Debussy conductor—check out his Jeux). At the same time, the jazzier bits make the right sort of racket, though I wouldn't swear that the busier passages are always perfectly lined up, and the final climax is a bit congested, with everything on top of you. (Interestingly, the first, more leisurely trumpet solo is relatively straight, but the second swings with Tin Pan Alley vigor.) The Cuban Overture rhumbas cheerfully along, as it usually does, though that woodblock no longer stands out quite as I remembered.

To fill out, or pad out, Maazel's LP program to CD length, the producers have added some very different Americana, from a very different conductor. Zubin Mehta's Appalachian Spring originally appeared in the two-LP set The Fourth of July!, issued in tribute to the U.S. Bicentennial; it's well recorded, in late-Decca analog style, and it's useful for a fine Ives Second Symphony. The Fanfare for the Common Man, which precedes the ballet, appears never to have been previously released.

The conductor's basically extroverted instincts serve Appalachian Spring plausibly, but juxtaposing Mehta's performances with Maazel's does the former no favors. Maazel's flair for detail could come off as self-conscious, but Mehta's more generalized approach, while suitably musical, seems generic: he's not probed far below the surface. His rhythms sound less solidly grounded, too: the faster dances, while suitably propulsive, sound skittish, or don't stay precisely aligned. And, after the high-powered Cleveland sonority, the capable Angelenos sound lightweight, occasionally underpowered.

Yet, it's the darnedest thing: for all of that, the performance actually works. You wouldn't mistake the level of commitment for, say, Bernstein's, but the wide open spaces of the broader music are wistfully reflective, the tutti reprise of the Shaker tune as triumphant as ever.

Overall, I'm glad to have this. Worth hunting down or looking into, especially for Davis's playing in the Rhapsody.

stevedisque.wordpress.com/blog