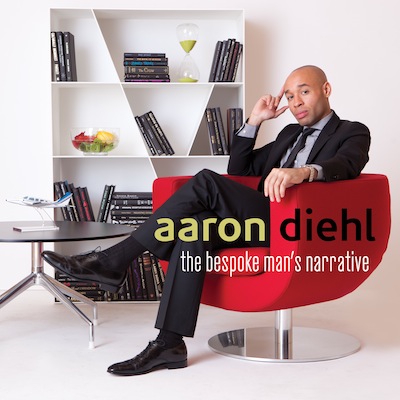

Aaron Diehl's 2013 CD The Bespoke Man's Narrative, his début on Mack Avenue Records, fell like a thunderclap upon the jazz landscape, reaching No. 1 on the JazzWeek Jazz Chart.

Something about the advance publicity must have caught my eye or ear, because I asked for a pre-release press copy of the CD. Upon playing it, I was so gobsmacked that I asked my friend and colleague Steve Martorella to come over to listen to it. Steve was a protégé of Leonard Bernstein's, and his principal piano teacher was Murray Perahia, so I think that it is fair to say that Steve probably knows a little about piano playing. While he was listening to the climax of Diehl's piano-trio version of "Bess, You Is My Woman Now," Steve was definitely getting tears in his eyes. His comment: "I didn't know that there was anyone new who could play like that."

In due course my comments on The Bespoke Man's Narrative appeared in Stereophile magazine. Since then, Aaron Diehl has released another small-group recording as well as a solo project. Next weekend (October 19 and 20) he will appear with the Rhode Island Philharmonic (under the direction of Bramwell Tovey) playing Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue. Mr. Diehl graciously agreed to answer a few questions.

Questions, answers, and a sound sample can be found after the jump.

What I wrote in Stereophile a few years back remains entirely valid (indeed, I am patting myself on the back for prescience):

Talk about a fascinating personal history. Rising-star jazz pianist Aaron Diehl's father ran a funeral home in Columbus, Ohio, with a largely African-American clientele. Diehl started at the piano with Bach, and not long after was playing in both the funeral home and a nearby Catholic church. I think the significance of those early experiences is not so much that a young teenager was already playing for audiences, but rather that he was playing in the context of rituals and, in the case of the funeral home, emotionally fraught major life transitions. I suspect that Diehl's unusual backstory is a large contributing factor in his musical maturity and poised artistic approach.

By age 13, Diehl had joined a jazz youth orchestra; by 16, he was playing solo piano in a hotel lounge; at 17, he toured Europe as part of the Wynton Marsalis Septet; that fall, he started studying at the Juilliard School, with Oxana Yablonskaya. In April 2011, the American Pianists Association awarded him (at age 26) first prize in the Cole Porter Fellowship in Jazz competition. That career-development grant provided the means to produce Diehl's first studio recording, The Bespoke Man's Narrative (CD, Mack Avenue MCD 1066).

This is one very self-assured recording. Diehl is joined by bassist David Wong and drummer Rodney Green on all tracks, and on all but two by vibes player Warren Wolf. Todd Whitelock recorded the album at Avatar Studios, and Mark Wilder mastered it at Battery Studios, both in New York City. Of particular interest is that Diehl plays a Fazioli 228 grand piano. If another studio jazz recording has been made with a Fazioli, I have not heard of it. The piano sound is exceptional—a combination of the Fazioli's bell-like clarity, Diehl's cool, every-hair-in-place pianism, and good engineering.

At times, Diehl's playing calls to mind Keith Jarrett's, and his group's sound is reminiscent of Brad Mehldau's trio. Diehl designed the CD as an integral program, with a "Prologue" and "Epilogue." Standout tracks include "Moonlight in Vermont" (sounding rather like an updated Modern Jazz Quartet), and trio settings of the Forlane movement of Ravel's neoclassical Le tombeau de Couperin and the Gershwins' "Bess, You Is My Woman Now"—the latter is a knockout, with some very impressive tremolo playing by Diehl.

There are risks in trying to assess an artist on the basis of a single CD, but I think that Diehl is more of a musical intellectual than a dispenser of emotional self-indulgence or of empty keyboard pyrotechnics. I think he is not so much detached as disciplined, and lacking in the eagerness to please the greatest possible number of listeners—not bad things, if you aspire to be a serious artist. Highly recommended.

(End quoted material.)

And now, for the Q&As.

Aaron, thanks so much for being willing to answer a few questions in advance of your appearance with the Rhode Island Philharmonic, October 20, details here.

Q1. I loved your first studio album The Bespoke Man's Narrative. What a self-confident and joyful record, with affectionate nods to the past—most of all, I think, to the Modern Jazz Quartet. Do you like that record as much as I do?

A1. Thank you! To be honest, I do not really listen to any of my records. I don't enjoy listening to myself unless it's necessary.

Q2. In 1942, the British Broadcasting Corporation began an interview feature called "Desert Island Discs." In 1965, Dmitri Shostakovich asked a variation on the "Desert-Island Disc Question" when he asked what musical score—what printed sheet music—fellow composer Rodion Shchedrin would bring to a Desert Island.

Shchedrin's answer was prompt: J.S. Bach's Die Kunst der Fuge. When Shchedrin then turned the question on him, Shostakovich answered, "Das Lied von der Erde, by Mahler." Two years before Shostakovich died, the two composers had the same conversation again; but neither had changed his mind.

- (a) What do you think of those two choices, and of the fact that neither composer chose anything by Mozart or Beethoven?

A2(a). I'd be interested in hearing their explanations, if that's on record. As a lover of J.S. Bach's music, I certainly understand The Art of the Fugue's being a Desert Island score.

- (b) Do you have any musical scores you would want to bring to that Desert Island?

A2(b). Am I allowed to upload a ton of scores to my iPad? Bartók: Concerto for Orchestra, Ravel: Daphnis et Chloé, Ellington: Such Sweet Thunder, Faure: Requiem, and Bach "Brandenburg" Concerti are just a few.

Q3. About your own Desert-Island picks for recordings, rather than scores:

Please tell us about the records that most influenced you as you were growing up, and then please list six to a dozen Desert Island recordings.

A3. I'll be glad to:

- The Complete Art Tatum Solo Masterpieces (originally recorded by the Pablo label 1953-1955)

- Monk Alone: The Complete Solo Studio Recordings of Thelonious Monk 1962-1968

- Martha Argerich: Robert Schumann Kinderszenen

- Oscar Peterson: My Favorite Instrument

- Miles Davis: Nefertiti

- Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings

- Rosalyn Tureck: J.S. Bach The Well-Tempered Klavier (Books I and II)

- Marcus Roberts: Gershwin for Lovers

- Rachmaninoff Plays Rachmaninoff (RCA Victor)

- Duke Ellington: Piano Reflections

Since these recordings were highly influential in my early musical development, I think it would be important also to take them to the desert island. It would be a reminder of what excited me about music in the first place… I occasionally have to do that anyway.

Q4. Are there any recording sessions from the past that you really wish you could have participated in? Things like, The Blues and the Abstract Truth, or Kind of Blue… .

A4. I would have loved to play on the Miles Davis Birth of the Cool sessions. Just witnessing Duke Ellington's famous 1956 concert at the Newport Jazz Festival would have been spectacular. I always feel the energy of that crowd during Paul Gonsalves' solo on Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue.

Q5. I was also hugely impressed by Cécile McLorin Salvant's 2-LP set WomanChild (also available as a CD). I put the first LP on the turntable without reading the jacket, but there was something strangely familiar about her accompaniment. Then I read the notes and saw that you were her musical director and pianist. How do the challenges of working with a singer differ from working with musicians in a small group, or orchestras?

A5. Cécile is a rare soul. Her musicality is unparalleled, but her primary focus is simply storytelling through song (i.e., the lyric). She's taught me a lot about telling a musical story without oversaturating the performance. The most direct route of communication is typically the best.

Q6. I think what Rhapsody in Blue shares with Beethoven's Fifth Symphony is that nearly everyone can identify both works just by their iconic four-note phrases. What are your thoughts and feelings about playing Rhapsody in Blue? Is the pluperfect familiarity of that surging four-note phrase as much a hindrance as a help, in getting one's own interpretation across?

A6. As an improviser exploring the realm of jazz in the context of orchestral music, for me it's all about strong motives that can be developed, embellished, and reimagined. Gershwin was a master at writing memorable tunes, so the question is: How do I want to weave in and out of the various themes he establishes? For a pianist who might improvise cadenzas in Beethoven concerti, I'm sure the same principle applies. Beethoven's famous cadenza for his Piano Concerto No. 1 immediately comes to mind.

Q7. One of the multi-layered pieces that I think made The Bespoke Man's Narrative so compelling was your jazz-trio treatment of the "Forlane" dance movement from Maurice Ravel's Le tombeau de Couperin. Have you ever given thought to performing Ravel's concertos?

A7. I'm not sure if there is anything to add to the Ravel, and honestly there are people who have devoted their lives playing his music who are much more qualified than I. Maybe my opinion will change someday—and you're not the first person to inquire about this.

Q8. Finally, in the longer run, what are your thoughts about other classical works with orchestra, and about future recording projects? I could easily imagine your recording Shostakovich's 24 Preludes and Fugues… or early keyboard music such as Bull and Tomkins on a modern piano. The whole gamut.

A8. I'll be performing Florence Price's Piano Concerto in One Movement with the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra (Joshua Weilerstein, conducting), in November, in addition to the Rhapsody.

What's interesting about this pairing is on one hand you have a white composer writing for orchestra with a strong inclination towards jazz, and on the other you have an African-American woman who includes elements of black folk music, but also has a strong 19th-Century Romantic influence (à la Brahms, for example) in her piano concerto.

Something about that is intriguing. As a musician in the 21st century who grew up loving Ellington as well as Ravel, I'd like to explore the challenges of synthesizing these influences without diluting the content or sounding contrived. That's difficult. Ultimately it would be great to compose and orchestrate my own works in various configurations, including orchestra.

JM: Thanks!

Sound sample:

Excerpt from Gershwin, "Bess, You Is My Woman Now," from The Bespoke Man's Narrative (Mack Avenue MCD 1066). Aaron Diehl, piano; David Wong, bass; Rodney Green, drums.