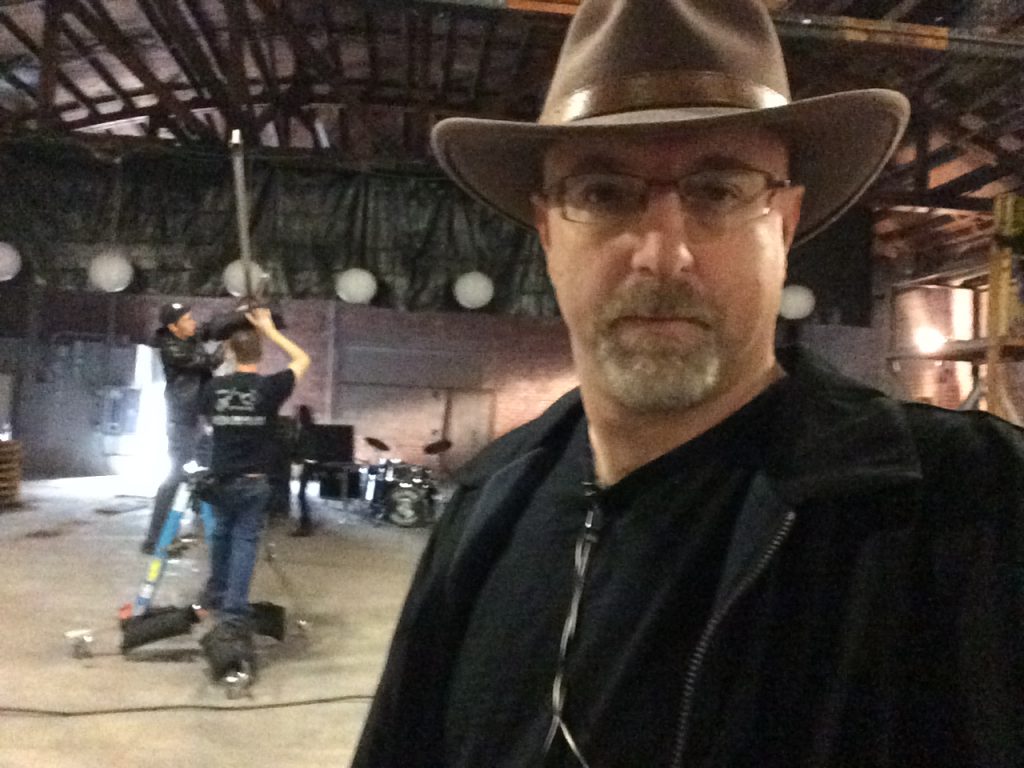

Twenty questions with an audiophile who is also an artist. For this Audiophiles as Artists, we feature Adam Goldfine who also writes for PF.

What's your background?

My interest in film and photography began around the age of 10. I loved going to the movies, started taking photographs, developing film, and making prints. I studied photography in high school and took several communications classes where we made shorts on super 8 film and reel to reel video. After high school I attended the Rochester Institute of Technology where I received an incredible education in the science and aesthetics of photography then graduated from New York University's film and television program where I studied film production and screenwriting.

After NYU the first film I worked on was Crocodile Dundee. It was an eye opening experience. Film production at that level was nothing like film school. The logistics alone were enough to keep you awake at night. Forget trying to marshal that many people to create a singular vision. It was the beginning of my true film making education which for better or worse, is best learned through a master/apprentice dynamic.

What's integral to the work of an artist?

Being able to create, to fulfill a vision as a filmmaker requires mastering a number of disparate skills to the point of their becoming second nature. You don't have the luxury of analyzing every choice, rethinking every decision. There is an enormous amount of planning and preparation that goes into mounting even a modest project, but then you have to be able to take whatever you are given on the day, (and there are so many variables and personalities involved there is no telling what that may be), and make it work.

There are some exceptions of course and that doesn't apply to every type of film making. With certain commercials for example, every element is so tightly controlled, story boarded, pre-visualized, that literally nothing is left to chance and the outcome is a foregone conclusion.

In either case you must have a vision. You must know what you are after and how to accomplish it whether you are improvising or working from advertising agency storyboards. There are times when, despite your best efforts, nobody has the full picture, can see the end you have in mind but you. It's okay. You just have to keep steering each element until it fits the whole that you have in mind.

Why do you do what you do?

I love film making. It's a constant challenge, to envision something exquisite and then work with teams of people, sometimes for weeks or even months to bring that to life, to see how close you can come to the original inspiration.

It's also a unique form of self expression, both in the creation and consumption of it. There is very little in the art world as complex as making a movie (large buildings considered as art aside) and there is nothing quite as involving for the viewer. So much can be expressed in a film.

I also love the collaborative nature of film making. It's both the challenge and beauty of it. I love working with people, inspiring people and being inspired by them, their ideas, their contribution, their enthusiasm.

How do you work? The process.

I like to do a lot of research first. Look at images, get ideas, consider possibilities. Little flashes of inspiration will come to me and I put them down, like building blocks. Here's something for the middle, this would be a good way to end, what about starting with this. Not everything will work for the whole so once I've gathered enough pieces I start to assemble them, ideas, see what starts to take shape, and then add anything that is missing while discarding anything that doesn't fit. There's a lot of instinct and intuition involved. It all starts with a blank page, with a question, what do you want to say, what do you want to create? An idea here and there begins to become an anchor piece on which other ideas are built. Eventually you end up with something complete. Then you have to communicate it to others, organize it, and execute the actual production of it. It's a bit of a nightmare to be honest.

What has been a seminal experience?

Attending NYU film school opened my mind to the possibilities of film making in ways I don't think I would have achieved any other way. Even though, after graduating, I lacked the mechanical and organization skills to be consider a true film professional, as I learned the craft and built my career, what I had been taught at NYU, how to think about a scene, how to create tension, and drama, to express ideas with visual efficiency, started to click until, and this was years later, I felt I had begun to master what I had been taught.

There were some excellent professors there. One in particular, Leonid Alekseychuck, who had immigrated from the Soviet Union with his family, had an enormous influence on me. I had grown up in suburban NJ so my experience of films was limited to Jaws, the Bond films, the Irwin Allen disaster movies, the Rocky Horror Picture Show, etc. I knew nothing about Fellini, Antonioni, DeSica, Bunuel, Truffaut, the French New Wave, Italian Neorealism. Alekseychuck had come up in a film making tradition that couldn't have been more different than what I had experienced up until that point. He was brutally honest. The film making world is incredibly competitive and his feedback was honest. If what you were doing sucked he would tell you it sucked. And I loved him for that. Sadly, some of the other students didn't like his honesty, wanted to be coddled, petted, and told that everything was okay. I could never understand that. I came for an education, to be trained, not to have my ego spared and told I was a good boy. He was among the best professors I had ever had and NYU let him go. Sad day.

What's the best piece of advice you've been given?

Good ideas are borrowed, great ideas are stolen. That was Alekseychuk. What he meant was that it was okay to be influenced by other filmmakers but don't just copy them. Make those ideas your own, build on them and turn them into something new. If the audience can see the influence, you've borrowed, if they can't, you stole it. Some of the greatest filmmakers of our time stole, and in some cases borrowed heavily, from the previous generation or generations. Some of the battle scenes in Star Wars are modeled directly after scenes of heavy artillery battles from World War II. Hitchcock was a master of suspense and is among the most widely studied filmmakers. Martin Scorsese's student film, It's Not Just You Murray is heavily and obviously influenced by Fellini, borrowed not stolen. But it also foretells the cinematic genius that was to become the hallmark of his later work.

Professionally, what's your goal?

I have a few. One of my goals is to be known as an auteur, a filmmaker who influences their films so much that they rank as their author. I feel I have a lot to say and while film is a collaborative art, part of why I do it is for my self expression. I absolutely have that control as a writer but it's a lot more difficult in film due to the collaborative nature. That's where having a vision and holding true to that vision come in.

Another goal is to be known as someone who is uncompromising in my commitment to quality and authenticity. Without honesty, art serves little purpose, in my opinion.

Where would you like to see yourself in 10 years as an artist?

Doing what I'm doing now, with one or more of my children.

In looking back, anything you wish you had done differently as an artist?

As an artist I don't think so. But I always advise anyone who wants to go to film school to get some professional experience first. School provides resources that you probably won't have available again for years. It's difficult for most people to take full advantage of those resources without the logistical and operation skills film making demands. And that's where a lot of film students fail. Organizing the people, equipment, locations, and other resources alone is mind boggling.

A couple of years in the industry, learning the craft, and you will come to film school fully armed to create something that is an expression of your artistic potential. It's impossible to express that potential if you can't figure out how to get the paint on the brush, so to speak. I would have worked for a few years first if I had it to do over.

What wouldn't you do without?

Family, friends, travel.

Is there a food, drink, or music that inspires you?

Food, elevated to an art form, is always inspiring. There are certain restaurants that, in my opinion, are so dedicated to producing the most exquisite result possible that it's inspiring. I'm not much of a drinker but I enjoy an occasional beer and find the micro-brew industry that has been evolving over the last 40 or so years absolutely delightful. Sierra Nevada is the first one I can recall that really stood out from the status quo and is still one of my favorites to this day. Music? Forget it. I love music, I play music, I am moved by music, there is always music in my head. That would be a whole other interview.

Or something else that inspires you?

People inspire me. I have a number of truly inspiring people in my life who are, I guess you could say, a reference point. Like, that's what true integrity looks like, that's what courage looks like, that's what compassion and honesty look like. It's a way for me to true myself up to the qualities that are important to me for myself.

How has your practice (art) changed over time?

Technology has transformed nearly every aspect of film making, from image acquisition to exhibition. In the days of actual film, everything required considerable funding. The cost of a camera was well into the six figures, renting a camera was also incredibly expensive, a roll of film lasting a little over ten minutes was hundreds of dollars (over $700 today), plus processing, printing, editing, conforming, more printing, titles, etc. Costs would add up quickly and would be considerable for anything other than a very rudimentary project. Home video cameras changed things somewhat but the image quality was so inferior to film that they were basically good for home movies, surveillance, etc.

In 2007 everything changed with the introduction of the Red One digital cinema camera followed by the introduction of the Nikon D90 and the Canon 5D Mk II roughly a year later. Cameras that could produce cinematic quality moving images were now in the low to mid four figures instead of the mid to high six figures. Film, processing, printing, etc, was all but unnecessary. Then along came the software, accessories, ancillary equipment, distribution platforms, everything to support a newly democratized film making industry.

What hasn't changed is the need for quality writing, acting, knowing how to light, block a scene, edit a cohesive story. In the past you didn't get to play with the good stuff until you had put in considerable time and learned the craft. Those that didn't were selected out by the competition. Now you can run down to Best Buy and have everything you need for a couple thousand dollars, learn the software and some camera tricks but a lot of what gets made is all sizzle and no steak. The fundamentals haven't changed.

I'm fortunate to have bridged two eras of film making, one that required years of practice and putting in the time to hone my craft, and the other that allows me to go downstairs, turn on the lights and make something pretty incredible looking with the equipment I personally own. But the technology has its own learning curve. The better cameras are actually simple and mimic a film workflow as much as possible. However the manual for the post-production software I use is over 2,700 pages.

What do you dislike about the art world?

Some of the people involved can be a little, or maybe a lot, dramatic.

What do you dislike about your work?

It's the schlepping. Film making requires equipment that needs to be schlepped to a location, set up, torn down, packed up, schlepped home, and unloaded. I like working in my studio but that's a pretty limited world given the location demands of film making.

What do you like about your work?

I love when it all comes together, when I start to edit and see how the vision is translating into reality. I like working with people, and putting the whole thing together.

How did you get into audio?

I've always loved playing and listening to music. Since my early teens I always knew there was something better out there. It's like The Matrix, I knew it was there but just couldn't quite put my finger on it. Even the best audio store in my town, Tech Hi Fi at the time, offered sound that was ultimately disappointing. I slowly upgraded through some of the mass market mainstays and was never more than disappointed. One day, in my early twenties, I was walking down Broadway in NYC and came upon a sign for the Stereo Exchange. I hopefully bolted up a flight or two of stairs to find an LP of Tim Hardin singing "Reason to Believe" spinning on a Linn LP 12 played through a pair of Dahlquist DQ-20s. It was like meeting Morpheus in the flesh. I began digesting everything I could about the high end and before long had acquired a VPI HW-19 Jr, a Conrad-Johnson PV-5 and a pair of Thiel CS 3.5s. I've never looked back.

Is there a relationship between you as an artist and audio?

Absolutely. The rhythm of music often conforms to the rhythm of film, and vice versa. I love making music videos and having an intimate knowledge of music, being able to play instruments, has made me a better filmmaker.

Where can we find your work?

https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0325600/?ref_=nv_sr_1?ref_=nv_sr_1

IMDB is missing a bunch of stuff and lists me as the assistant boom operator on a TV movie for some reason, but it gives you some idea.

Anything else that you wish we had asked?

I don't think so.