BACK IN BLACK

The vinyl is back for good. If there are people who haven't noticed this yet, they are clearly the sort that have no interest in music, know nothing about the younger generation, don't pay attention to the changes in design and don't understand the changing contemporary society. In other words, people completely detached from what's "here and now". Moreover, they don't cherish the past, either. Because vinyl is a bridge between what's "old" and "new"; on the one hand, it's an artifact of the past, related to the nostalgia for the "good old days", but it's also an ultramodern reflection of various movements in the music industry, which go along with the mainstream but are quite distinct at the same time.

For the informed, experienced audiophile, the deal is simple: flagship turntables are still the best method of music playback in a home environment. A reel-to-reel tape recorder is even better, but only if we have access to early-generation copies from the master tapes. Transferring the material from the LP or CD onto the tape is completely pointless. Even transfer from the DSD file seems a bit suspicious to me. I believe that recordings should be played back in the same format they have been recorded in. This might be an idealistic approach, but I just can't help it—being an audiophile is all about being an idealist anyways.

The biggest part in the resurrection of the vinyl was played by DJs, meaning the general mainstream (even if they themselves believe otherwise). They were the ones who woke up the awareness of an "analogue sound" within the youth, something commonly associated with a "warm", "soft", "human" and "pleasant" sound. This isn't audio magazine terminology, but rather quotes from newspapers and radio shows, and I hear them every time a musician talks about this "new" medium. It immediately becomes obvious that they have no idea how much more vinyl has to offer, but the intentions are good and so is the general direction in which this has gone. This is crucial, since they are the trend-setters for the fashion we're dealing with now, the fashion for the "black disc".

It's worth keeping that in mind when we listen to the pimped-out, refined vinyl re-releases from the companies like Analogue Productions, Mobile Fidelity, Audio Fidelity, ORG (Original Recordings Group), Pure Pleasure Records as well as many other, smaller record labels. They are not the ones behind the vast majority of record sales; they are—like our entire branch of audio—perfectionist companies and therefore they operate within a very small niche. They are certainly a reference point, and they set out the directions as well as display the possibilities in the audio world. A crushingly large proportion of the vinyl LPs currently bought by music lovers, young people as well as nostalgic "greybeards", are released by large companies that up until recently firmly believed that digital media are the only possible direction to go to within the audio world.

MUSIC ON VINYL

The 7-inch singles' press.

Yesterday, when I visited Saturn - a Polish electronics megastore with computers, video games, pots, pans, and cheap hi-fi systems—I ran my fingers through a rather large shelf displaying the store's vinyl records. It's a retail store with possibly the largest selection of records, some of them even from limited editions, like those specially made for Record Store Day. The presence of the black disc in a store that is oriented to mass, quick retail sales, is a total surprise to me. We aren't talking about discreetly hidden album sleeves with outdated technology inside, but rather a huge jewel in the crown of the entire music aisle. It's something truly unbelievable in the day and age when the shelf space for CDs dwindles from day to day.

If you take a closer look at the records displayed, you can notice the very same sticker on most of them: "Music on Vinyl". This brand, unknown in the "golden age" of the analogue, is currently one of the biggest, if not the biggest supplier and promoter of the black discs.

One of the 33 presses for the 12-inch discs.

The story begins in the mid-1950s. As Robert Haagsma writes in his book Passion For Vinyl, the brothers Casper and Will Slinger were jazz lovers. They usually bought their records in a little store called Glorie, in Amsterdam's old city center. That's where they befriended John Vis, a worker at the store. The result of their conversations was the idea to start their own record label. Artone was founded in 1956, their slogan being "C'est l'Artone qui fait musique", or (loosely translated) "(Ar)tone makes music”. Initially, the discs were pressed in Germany, but by the end of the 1950s they built their own record press.

In the mid-1960s—largely due to label's manager, Peter Bouwers—the company rapidly grew and in addition to local artists started also releasing those from across the Big Pond. It became the biggest independent record label in the Netherlands. Artone got licenses from ABC Paramount, Cameo-Parkway, Hickory, Chess, Motown, Reprise, Roulette and CBS Records. It therefore signed deals both with small companies as well as with the giants of the music industry. When they bought their own printing plant in 1966, the entire production could be carried out "under one roof".

Cutting a copper stamper – "DMM Cutting".

These were times in which CBS Records grew strong. A logical step forward for them was buying Artone's shares, which happened in 1966. Three years later, this giant label, which released albums by Bob Dylan, The Byrds, Janis Joplin, and Simon & Garfunkel (to name a few), bought out the whole Artone. The record label was still called Artone (although the publishing company wasn't), but the name disappeared in the 1970s.

During these years the company experienced another growth spurt, to the point of owning their own dedicated trucks for distribution. At the same time, the pressing plant in Haarlem, the part of Amsterdam where Artone had its headquarters, was chosen as "the best CBS producer in Europe". In a very short time it turned out to be the best CBS record producer in the whole world, beating the two pressing plants in the USA as well as the one in Japan, which was obviously very difficult to surpass.

In the 1970s, it was artists like Miles Davis, Paul Simon and Neil Diamond, with Bruce Springsteen and Michael Jackson in the 1980s, which made things even better for the Dutch branch of CBS, which was called CBS Grammofoonplaten at the time. Jackson's album Thriller was sold in the unbelievable number of 110 million copies, of which 35 million were pressed in Haarlem. At the time, the label was annually pressing around 50,000,000 discs. But the years of prosperity were numbered, and cut short by the appearance of the CD. This wasn't immediately visible, though, and initially many people didn't believe that this format could earn the general public's approval.

The positives and negatives are made here.

In 1988, CBS was bought out by Sony. As Robert Haagsma says, it wasn't just about changing the logo on the albums. The new owner was, after all, the co-owner of the Compact Disc patent. According to Peter Bouwens, it was obvious that Artone would eventually start pressing CDs, too. The transition seemed natural and unavoidable.

At that moment, however, there happened something that had been impossible to predict, or actually someone, to be precise: Otto Zich from Austria. He had very good relations with the local authorities and, at the time, he travelled several times to Japan to convince Sony that he was the only person capable of ensuring the highest-quality digital disc production for them. Things started happening lightning fast. The "Austrian" option was supported by the Sony representative for the USA, Dick Asher; the "Dutch" option was supported by the European Sony representative, Bob Summer.

At the meeting with Sony's management board, Bob showed up empty-handed because he forgot to bring the contract, putting all his faith in the value of the huge, experienced record label. Dick, on the other hand, arrived with a ready contract, and—as it turned out later—nothing but a "hole in the ground." He didn't have a place, people or any experience in disc pressing. Sony's management made their decision very promptly, however, and handed the keys to their treasury to a man who was ready to sign the contract then and there. And they weren't disappointed. Otto turned out to be an excellent entrepreneur and the company he ran developed into the biggest pressing plant of its kind in Europe, and one of the biggest in the world. Until this day, most silver discs, as well as SACDs, come from Austria—you can check out the laser engraved details on the inner side of the disc. The good, old Artone was thus sentenced to its downfall.

How positives and negatives are made.

In the 1990s, Sony didn't know what to do with their Dutch pressing plant. And just as previously Otto Zich had turned out to be the greatest disaster, Tom Vermeulen now came to the rescue. He was one of the biggest customers for the discs pressed at Haarlem, and together with Marcel Nothdurf and Omca Vastgoed, in 1998 they signed a contract with Sony and became the owners of the whole plant. This way, Record Industry was born on June 1st, 1998.

At the time, founding a company that had anything to do with vinyl seemed like a completely pointless idea, because everything seemed to suggest that the CD was going to be the only widespread consumer format. In Passion for Vinyl you'll find, however, that Ton Vermeulen had an ace up his sleeve—the contract stated that Sony had to press their black discs in Amsterdam. He was convinced that sales were going to rise—the complete opposite of what Sony's management was expecting. In their yearly reports, the Japanese syndicate predicted that in the year 2000, no more than 10 million black discs were going to be sold worldwide. In reality, anywhere between 200 and 250 million were sold (the sources vary). The black disc was saved by DJs and 12-inch EP discs.

And all was well, the Dutch pressing plant was working at a steady pace. Unfortunately, after some time, part of the clubbing world moved on to audio files, and the vinyl production began to dwindle. This didn't break the spirits of the owners of RI, though. After a few weaker years, Ton, together with the Dutch dealer Bertus, opened in 2008 their own record label called Music For Vinyl, part of Records Industries, believing that it would be the answer to their problems. As it turned out, the idea of founding their own record label was a bulls-eye hit and it began an exponential avalanche of orders for them.

Cutting the centering opening in the stamper.

The company started off with the mindset of dealing with re-releases of Sony Music, Universal, and Warner albums. The pressing is being done on machines that may often be several decades old, but have been kept in very good condition. The records are released in series, such as: "Classic Album", "Available For The First Time On Vinyl", "Exclusively Remastered", but also "New Album"—these are albums that are being currently recorded, whose vinyl edition is released simultaneously with the digital one. Aside from classic black discs, Music On Vinyl also presses discs on colorful and transparent vinyl. They also release limited, individually numbered collectors' editions.

The small, specialist companies I talked about at the very beginning, which deal with re-releasing classic albums, are the salt of this earth. They offer perfectly-prepared, fantastically-sounding albums, which have been available for years, for thousands of dollars, on eBay, for example. This is but a drop in the sea of needs, however, and it's a very expensive method of enjoying your hobby of listening to music on black discs.

Music On Vinyl offers something incomparably larger, which could support the entire industry. The number of albums in their store is huge, and their prices aren't prohibitive. To be able to do something like that, you have to give up doing the most basic things a record label does—you have to use ready-made remasters and press the discs from digital files, as well as pay far less attention to the ideal conformity of the cover and center label to the original album. The scale we're talking about here doesn't allow for anything else, though. Such is life.

Negatives waiting for further processing.

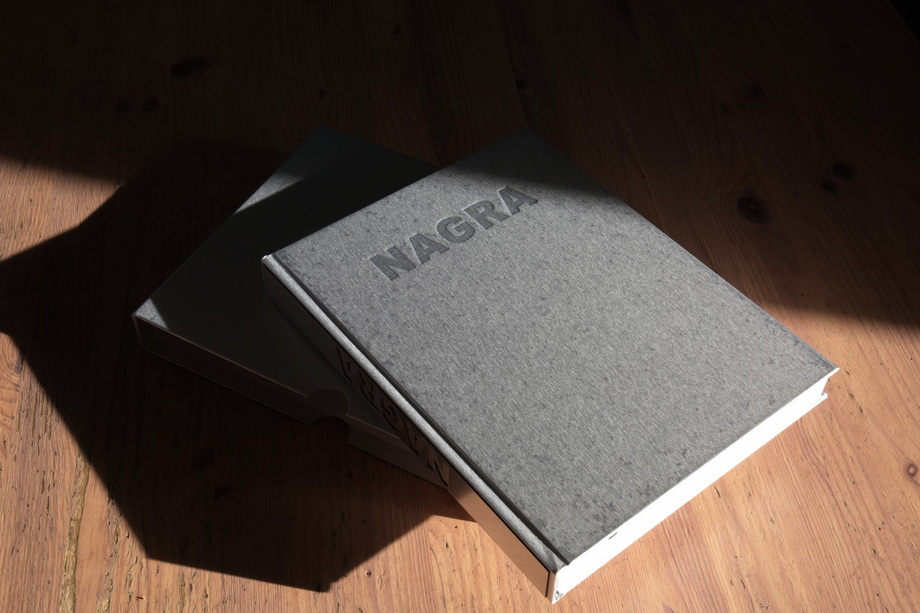

In Passion For Vinyl, which I relentlessly used as a reference while writing this article, Robert Haagsma paid tribute to Record Industry; I reviewed the book HERE. In an attempt to introduce it to "High Fidelity" readers, I asked Robert a few questions, and you can find the answers to them below. A follow-up to this story are the interviews with Anouki Rijnders and Erik Guillot, a sales manager for Music On Vinyl and a marketing manager for Record Industry, respectively.

The remainder of the editorial includes reviews of a few selected albums, all of which come from different series, as well as A Second Perspective, an alternative opinion about a re-release of the Alan Parsons Project, written by Bartosz Pacuła, a 20-year-old representative of the younger generation.

A FEW SIMPLE WORDS WITH…

ROBERT HAAGSMA | Passion For Vinyl

Editor, author

Where did you get the idea that vinyl can be an interesting subject?

Vinyl has been making a comeback since a couple of years. I totally understand why. Lots of things have become invisible because of downloads: books, movies and music. There are still people who are willing to pay for music, but like to get something great in return: a vinyl record. For many people, playing a record or holding a sleeve in your hand truly adds to the experience of listening to music. People often have lots of memories attached to particular records. It's that love and passion that I wanted to capture. Not only from fellow collectors, but also from people who work with vinyl professionally, like musicians, record store owners, label managers, engineers and designers. They all have their own story, and I find them all very interesting.

What is the worst sin of vinyl?

In my opinion, high prices are a problem. Some records are 25 Euro which is ridiculous to me. I also don't like bad pressings or lousy reproductions of sleeves of reissues. But I have to say that lots of record companies put out great stuff. I rarely have to return a record because it's faulty.

Mastering studios, with active Genelec monitors.

Is this trend, I mean growth, something steady that will continue in the future? Or will it die out and when?

The revival has been going on for five, six years now, so I think it's more than a trend. I think it is important that young vinyl lovers invest in a good turntable and learn how to handle, clean and store vinyl. If not, many people will become frustrated about the vulnerability of vinyl and return to MP3's and streaming. Having said that, I think there is a healthy future for vinyl. People will always love music. And there is a collector inside many of us. Vinyl is the perfect collector's item.

What do you think of the digital revolution and high-res audio files? Is this our future?

Yes, this is the future. A small part of the music lovers will stick with vinyl. The masses have already chosen Spotify and other internet services. This will only increase. CDs are on their way out – fast.

Are you working on a new book?

Not for the moment. It's great to work on a book like Passion for Vinyl, but it also takes a lot of time. I am sure there will be more books down the line…

The lacquer disc cutter - the first step in making a vinyl record.

Could you give me a list of ten albums that High Fidelity readers should buy on the spot?

Whew, that's a tough one, because I don't know what music your readers like. Let me spread it out over various kinds of music:

• 60's garage: 13th Floor Elevators, Psychedelic Sounds of…

• 60's psych: The Zombies, Odessey and Oracle

• Folk: Fairport Convention, Liege & Lief

• Early hard rock: Black Sabbath, Black Sabbath

• Prog: King Crimson, In the Court of the Crimson King

• Great Dutch rock: Golden Earring, Moontan

• Punk: Ramones, Ramones

• Reggae: The Congo's, Heart Of The Congo's

• Metal: Slayer, Reign In Blood

• Avant Garde/Post metal: Ulver, Messe I.X-VI.X

What is your audio system to listen to the music?

I have three turntables: Linn LP12, Linn Axis and Thorens TD 160B. Densen amp, various phono amps (i.e. Primare), Nakamichi tape deck, Sony SCD 777 ES SACD player, Amphion Xenon speakers, Siltech and Vandenhul cables.

Do you think that sound quality is important part of a given album's artistic expression?

YES, I know many people disagree, but I think sound quality adds to the emotional experience. Artists and bands often spend thousands in expensive studio's to make great recordings of their music. It's sad when people play it on their iPhones or on cheap stereo sets. It's like watching a move with dirty glasses. When I play a well pressed Frank Sinatra record, he actually walks into my music room. Old, original Blue Note vinyl records have a similar impact. These recordings take my breath away, because of the beauty of the music and the love and skill that went into the recording. I recognize a good tune on a cheap radio, but to really enjoy music I need good sound quality.

ANOUK RIJNDERS | Record Industry

Sales Manager

These granules will form the vinyl "pancakes" which are then compressed by the stampers.

Tell us briefly the story about Record Industry.

Record Industry started in 1998, founded by Ton Vermeulen who took over the plant from Sony Music. Ton at that time had a few record labels of himself (in dance music) and Sony wanted to stop production and sell the plant. Both parties came together and Record Industry was a fact. (more detailed description can be found in the book Passion For Vinyl).

Where did the idea of Music For Vinyl come from?

MOV is a collaboration between Bertus and Record Industry, a vinyl only label, started 5 years ago. It started with classic titles from the Sony catalogue but has now grown massively with a catalogue of over 1000 titles from several major but also smaller record labels. (In Passion For vinyl a detailed description can be found).

Who decides about pressing these and not other titles?

As far as MOV is concerned, it is the MOV team decided that, often inspired by suggestions from consumers.

How did you start working for RI?

I already knew Ton for a few years before I started working for Record Industry in 2000. It was really busy at the factory and he asked me if I wanted to help him out in the office with all kinds of work. It was not my intention to work for RI for a long time, originally educated to make documentaries and television programs, but I'm still here after 14 years... Vinyl is a great product to work on and I love the factory and all my colleagues.

Vinyl "pancakes", ready to be transported to the press.

You've already mentioned your background…

As written above, I come from television work. But music was my first love, my first job was in a CD shop and from a very young age I listened to music at home and bought my own records.

Record Industry has its own pressing plants, but who is responsible for lacquer disc cutting?

Record Industry is privately owned and has its own pressing machines, cutting studio's and mastering studio, Next to that we do our own DMM (Direct Metal Master) manufacturing and have an in-house galvanic department, packaging department and folding machines for sleeves. In the same building there is a printing plant as well, with strong ties to Record Industry.

Changing the stamper.

How does your pressing plant differ from others? And what about your pressed vinyl records?

As described above, we do almost everything in house, apart from PVC production, not many pressing plants can say that (if any). Our quality and the one stop shop are our unique selling points. Our CQ checks each new cut/development prior to pressing finished product and also in between the several production stages the product is checked.

What do the numbers look like—how many records do you press yearly, and how does that figure change from a year to year?

Last year we pressed 4 million records, the year before about 3.5 million. We expect to be pressing between 4.5 and 5 million records this year.

Changing the stamper.

Do you think that there is future for vinyl-oriented companies and labels?

Yes, there is, vinyl is a format which will last for a very long time. People want to have physical product, vinyl is value for money compared to CD or downloads. It's collectible and also an emotional product, it's a possession. And for the high-end/hi-fi audience vinyl is most preferred above CD.

ERIK GUILLOT | Music On Vinyl

Marketing Manager

Wojciech Pacuła: Tell us a few words about Depeche Mode rereleases.

Erik Guillot: The idea comes from the band and its record label to issue high grade 180 gram audiophile reissues through a partner like MOV for Europe, as we are known to put the highest standards in quality vinyl products.

A vinyl "pancake" on the stamper.

Have you used the same master as the 2008 edition?

The masters used are the same as the 2008 edition. The cutting took place in Haarlem at Record Industry by Rinus Hooning, a master cutter with 40 years of experience working for the CBS record plant that used to be in the same location

Tell us the process of record preparation.

When obtaining the audio from the label (in this case 24-bit 192kHz digital files) the test pressing is made in DMM (Direct Metal Mastering) by Rinus, after which we and the record label (perhaps the band as well) are checking the reviews for the desired sound quality. If anything is wrong, the test pressing/master cut is made all over again. After the test pressing is OK-ed by all parties involved, we'll start up the press making vinyl from a negative (mould) of the metal cutting (with 'mountains' instead of 'valleys', by pressing those into vinyl the 'mountains' will create the groove. Every so many copies are checked for mistakes or pressing errors. The vinyl records are automatically packed into plastic lined inner sleeves and stored / cooled until packaging.

The label-sticker machine.

Meanwhile, the artwork has been printed by the printer (in the case of Depeche Mode these are gatefold sleeves) and the insert is printed as well. When the records have been sufficiently cooled, they will be packed by machine into the gatefold sleeves along with the inserts and wrapped in plastic and stickered, and packed in protective boxes for shipping.

Automatically packaging the discs in protective paper envelopes.

The machines are several decades old

Text by Wojciech Pacuła,

Images by Bert Treep | Wojciech Pacuła,

Translation by Andrzej Dziadowiec