It is the story of birth of digital audio, as well as a journey through the 1970s and 1980s, the best period in the history of digital recorders, and finally the story of their unique representatives; reel-to-tape recorders from Mitsubishi. (Part 1 can be found HERE)

DIGITAL SOUND RECORDING

method of preserving sound in which audio signals are transformed into a series of pulses that correspond to patterns of binary digits (i.e. 0's and 1's) and are recorded as such on the surface of a magnetic tape or optical disc. ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA; accessed on: 09.04.2020

In the first part of the article, we looked at the first digital audio tape recorders—reel tape recorders from Denon, Soundstream, 3M and Decca. Finally, we recalled Sony as the one that ultimately won the battle, which was about the emergence of a common, digital mastering system, i.e. the final medium used to deliver recorded material from studio to an LP pressing plant and later CD. As it turns out, these systems were only an introduction to what took place in the 1980s, that is, to the rivalry between Sony and Mitsubishi. Both companies have argued that their digital recorders should be used in every modern recording studio. Who won? What is left of it?—let me invite you to the Part 2.

One of the first Decca albums digitally recorded—this one is an SACD version released by Esoteric

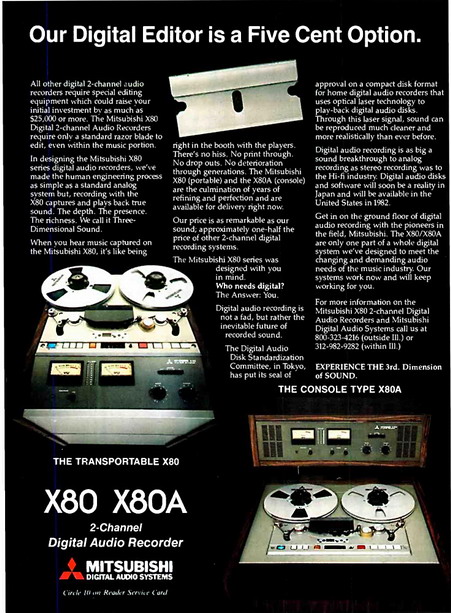

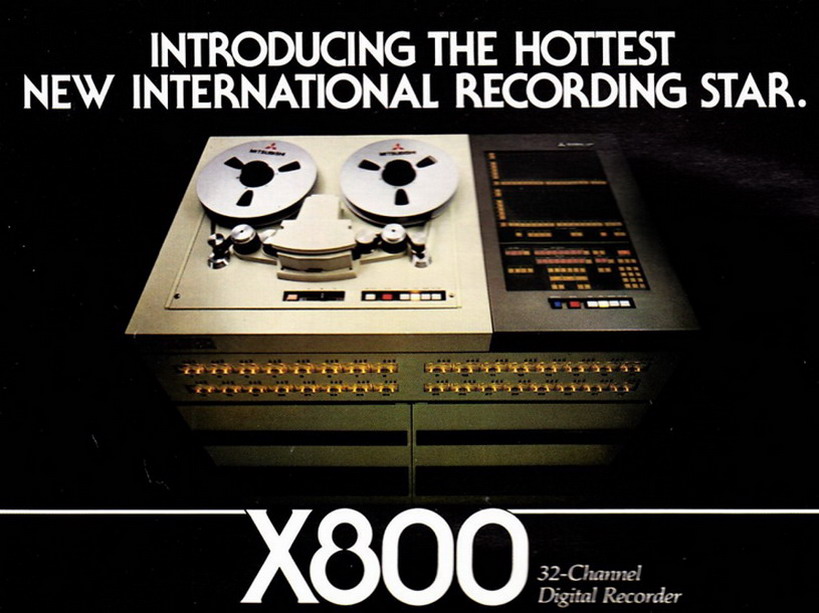

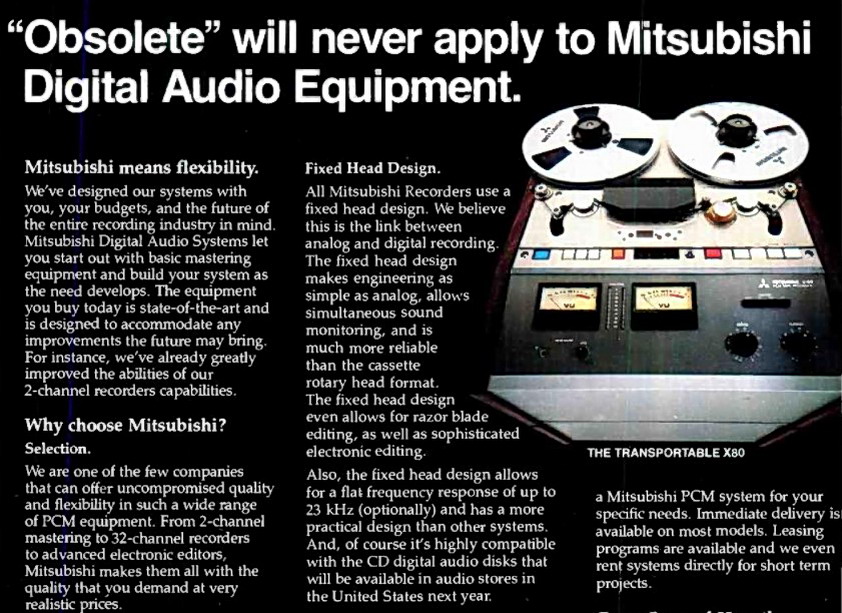

In the issue of June 12th 1982, then the bible of the professional music world Billboard announced the official launch of the 32-track Mitsubishi X-800 reel-to-reel digital tape recorder, accompanied by the XE-1 electronic editor. The presentation took place at the A&R Recording Studios—located in the former Columbia Records headquarters, Studio A. The show was led by Lou Dollenger, national sales director of Mitsubishi Digital Audio Division, responsible for the US market. He claimed: "I think our system can coexist with Sony's." What was he talking about? What did he mean? As usually, about the money.

SONY's PERSPECTIVE PRIOR TO THE STRUGGLE

Sony has already presented the first digital recording device in 1974. It was a prototype based on video tape transport using a 2" magnetic tape. However, it wasn't until 1977 that a commercial product was ready that had almost nothing to do with the prototype—it was a digital processor PCM-1, working with an external cassette recorder U-matic (it was a video recorder). This is how the mastering tape recorder was developed that was used until the 1990s by most major recording studios.

What the company needed still was a multi-track tape recorder. The 70s was the peak period in the field of multi-track recordings, made using analogue tape recorders, usually designed by Studer. The basis was 24-track recordings, but after synchronizing two tape recorders, one could prepare recordings with forty-eight "tracks." And this is what the music industry needed.

In 1981 (according to www.mixonline.com magazine, and in 1982 according to Wikipedia) Sony had prepared a prototype of a digital tape recorder PCM-3324. It was a device based on a tape transport and offered 24-digital tracks. The tape recorder recorded PCM signal with 16-bit and 44.1 / 48kHz parameters, weighing 250kg and it cost USD 150,000. The ½" (13 mm) tape could record up to 65 minutes of music and it was possible to synchronize two devices which resulted in 48 tracks altogether.

The Sony solution, however, differed significantly from almost all such devices from the past—because it featured a stationary head (all previous ones had rotating heads). Sony called this system Digital Audio Stationary Head, in short DASH. The advantage of this solution was low failure rate and much easier operation. The advantages of the system were quickly noticed by musicians and early users of the PCM-3324 tape recorder were Stevie Wonder, Frank Zappa, OMD, New Order, Dire Straits, Jeff Lynn with the ELO and others. The option of renting these devices also contributed to their popularity.

The DASH system was scalable. Company offer two-track tape recorders using ¼ tape called PCM-3402 and PCM-3202 (as well as Studer D820x), 24-track - models: PCM-3324, PCM-3324A, PCM-3324S, and later also 48-track ones, such as PCM-3348 and PCM-3348HR. Studer and Tascam also joined the Sony's "camp", and these brands produced their own DASH tape recorders. Almost all offered 16-bit recordings with a sampling frequency of 44.1 or 48 kHz (selectable). The only Sony model that recorded a 24-bit (44.1 / 48kHz) signal was the PCM-3348HR (and Studer D827), so it was used for many years, for example by Deutsche Grammophon studios, even when hard disk recorders were already available.

Sony was not the first company to offer digital recording, because Denon, Soundstream and Decca had done it before them (as described in the first part of the article), but thanks to the DASH system Sony was back in the game. However, the company had a problem and they couldn't find a work around for it—at the time of the presentation the PCM-3324 tape recorder was not yet ready for serial production, and it was not sold until 1984. One of the first units were tested by the Dire Straits on the Brothers in Arms album. In the year when this system was presented to recording studios, there was already a competitive tape recording system on the market, also based on a stationary head, called ProDigi, developed by Mitsubishi.

Mitsubishi ProDigi

Mitsubishi Group (三菱グル ープ, Mitsubishi Gurūpu), also known as the Mitsubishi Group of Companies or Mitsubishi Companies, is a group of independent Japanese international companies sharing the Mitsubishi brand and its trademark. Mitsubishi was founded in 1870, two years after Meiji Restoration, and its main business was shipping.

Diversification in later years mainly concerned related fields. The company invested in coal mines, using this raw material to power its extensive steam fleet, bought a shipyard from the government to repair the ships it used, founded an iron mill to supply iron to the shipyard, and a maritime insurance company to handle shipments. Let's add that during World War II, Mitsubishi produced aircrafts under the direction of Dr. Jiro Horikoshi. Mitsubishi A6M "Zero" was the main Japanese naval fighter during World War II.

Stereo

One of the areas that the company dealt with in the 70s was the pro-sound. The company already presented a prototype of a multi-track tape recorder in 1977, but like Sony, the device was ready for production only a few years later. The first digital tape recorder that came into production was a stereo device, which happened in 1980, and the tape recorder was named X-80.

This is one of the most interesting digital recorders in history. It was designed by the Mitsubishi engineer who also happened to be an audiophile, Mr. KUNIMARO TANAKA. It featured matching transformers in the inputs and outputs, and discrete electronics and it operated in A class. On a ¼" tape spinning at 38 cm/s one could record up to 60 minutes of material. It was to be a mastering tape recorder, i.e. one used fr recording already mixed material intended for LP pressing, and then also for CDs. In later years, it was also used as the main recorder during "direct-to-two-track" recordings.

The device had a fixed head, but nominally it was not a ProDigi tape recorder yet. Its special property was the sampling frequency of 50.4kHz (the 44.1 / 48kHz standard was adopted only in 1985), which at 16-bits of resolution resulted in dynamics greater than 90dB, frequency response from 20 Hz to 20 kHz (+ 0.5 dB / -1dB) and distortion below 0.05%. Thanks to the use of high-class, analog output filters, the frequency response reached up to 24kHz. From a technical point of view, these were much better parameters than those of any analogue tape recorder. And that was the whole point—improvement. The tape recorder cost $5000 and 200 units were produced by 1986.

Mr. Tanaka's tape recorder was designed to look like an analog device and to be operated in a similar way. Thanks to the stationary head, the tape could be edited similarly to classic tape recorders - by cutting and gluing it back together. What's more, most of the sound engineers thought that the sound quality of the X-80 was excellent. The device quickly found a place in many important recording and mastering studios, and one of its early promoters was TOM JUNG, the founder of the DMP label.

In an interview for Stereophile he said:

[X-80] was unique in that it was designed by a Japanese engineer who happened to be an audiophile, knew about discrete class-A electronics, and used them in the X-80. He was also aware that there were inherent problems in the PCM format, so he compensated for them, correcting phase errors created on the record side in playback. To a large extent, he was successful. We'd record and play back in the studio, and musicians always liked the way the X-80 sounded.

But it had the god-awful sample rate of 50.4kHz. By the time I got to the mastering stage and had to convert that 50.4kHz to 44.1kHz in the digital domain, the mathematical formula led to significant losses.

Two SACDs in our catalog, Flim and the BB's' Tricycle and Jay Leonhart's Salamander Pie, were made directly from Mitsubishi masters. When I made the SACD versions and couldn't go from 50.4kHz to 1-bit DSD in the digital domain, I remembered that machine had always sounded good playing tapes that it recorded. So I used that same machine and the original master tapes, the ones that actually had razor-blade splices.

DAWID LANDER, Tom Jung of DMP: Making Musical Sense, www.stereophile.com, accessed: 11.05.2020

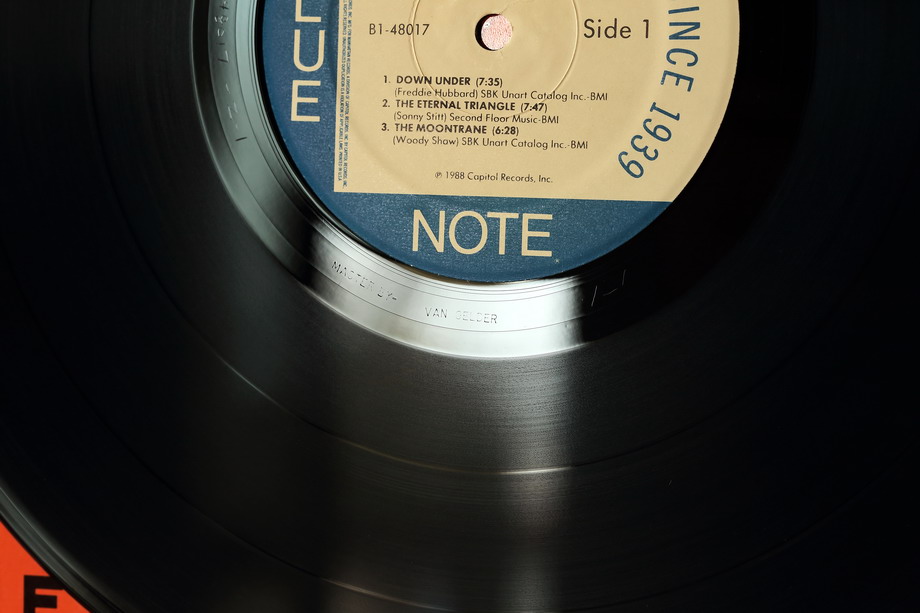

The A-80 was the first Mitsubishi digital cassette recorder featuring fixed head (the X-80A version featured an external module with VU-meters). In the following years further versions were developed, first the X-86 (1986), supporting 44.1/48kHz sampling frequency, and later the X-86HS, the first digital recorder in the world supporting a sampling frequency of 88.2 / 96kHz. However, they were stereo tape recorders. And although many studios performed live recordings directly on two tracks—among them Rudy van Gelder for Blue Note—although the Fantasy company used it to remaster their catalog, the actual battle took place in a different field—in a multi-track recording.

32-tracks

In 1982 Mitsubishi proposed a 32-track tape recorder designated as the X-800, working with 1'' tape. The series initiated in this way caused a short-lived but fierce "battle"—another one in this industry—between DASH and ProDigi systems. The industry split between these two camps—Sony was supported by Studer, Tascam, and Mitsubishi by Otari and AEG. In the mid-1980s, Billboard published an article titled Digital over Analog in Two Years, in which they talked about "war," which was in "full swing."

In retrospect, we know that no one came out victorious from this war, because systems using hard disk reconciled (beat) them all, but it is generally believed that Sony finally gained the upper hand. According to Samantha Bennett, "from the mid-1980s to their end, the DASH format became the first choice of many professional recording studios and in 1986 over 300 devices of this type were sold." This Pyrrhic victory was achieved in two ways. On one hand, Mitsubishi multi-track tape recorders were known for their high failure rate. On the other hand, it seems, Sony was better at promoting its system.

I do not know if I read the statements of sound engineers and producers correctly, but it turns out that in terms of sound quality, Mitsubishi devices were preferred. They featured a great system protecting against errors and very good electronics. In 1985, an improved tape recorder hit the market the X-850 with parameters similar to X-800, but offering greater editing capabilities. Its transport was borrowed directly from the Otari MTR 90 Mk II analog 24-track tape recorder. Therefore, on the market there were also Otari DTR-900 tape recorders, technically very similar to the Mitsubishi X-850.

It is known that further versions of tape recorders were planned—in 1988, the multi-track X-880 and the stereo X-96 production was supposed to begin. However, it did not happen. The company withdrew from audio, and only Sony remained on the battlefield. In the same year they presented the PCM-3348 and PCM-3348HR, which recorded 48-tracks on the ½" tape - the latter in 24-bit resolution (which is why the company used the DASH Plus name for it). Mitsubishi tape recorders, however, remained in many of the best studios in the world - most of them in Nashville, where in the 1980s the vast majority of country music was recorded and mixed on one of the ProDigi tape recorders.

Mitsubishi digital tape recorders were used both as permanent equipment for recording studios and as rental equipment. It was an extremely expensive piece of technology, because although the X-800 was initially to cost USD 240,000, and after the premiere its price dropped to 175,000 USD, it was still an unbelievable sum of money. Renting it wasn't cheap either—as DAVID HEWITT, a well-known sound engineer working with the biggest bands in the world, recalls, when he worked with the Pink Floyd group on the A Momentary Lapse Of Reason album, rent for a single day for this tape deck was $ 10,000:

We had been on tour with U2, recording for the film and album Rattle and Hum, and my Black Truck would be traveling between gigs on those dates. I had to find another truck fast! I knew Gary Hedden as an engineer and that he had built a new remote truck capable of meeting Pink Floyd's requirements: recording to a pair of Mitsubishi X-850 32-track digital tape machines along with two 24-track analog machines for the drum tracks!

I booked Randy Ezratty's Effanel company to record the N.Y. Pink Floyd shows. Randy had recently purchased the Mobile Audio remote truck out of Atlanta, and I had used it to record Prince on some of the Purple Rain tour, so I was confident with the package. In those days equipment rental companies provided the hyper-expensive digital tape recorders. The Mitsubishi X-850s were probably sourced from Audio Force or Jim Flynn Rentals at around $1,000.00/day times two, plus cartage! Effanel already had two Otari MTR-90 24-track tape recorders.

David Hewitt, Road Diaries, Entry 6, blog.audio-technica.com, accessed on: 11.05.2020

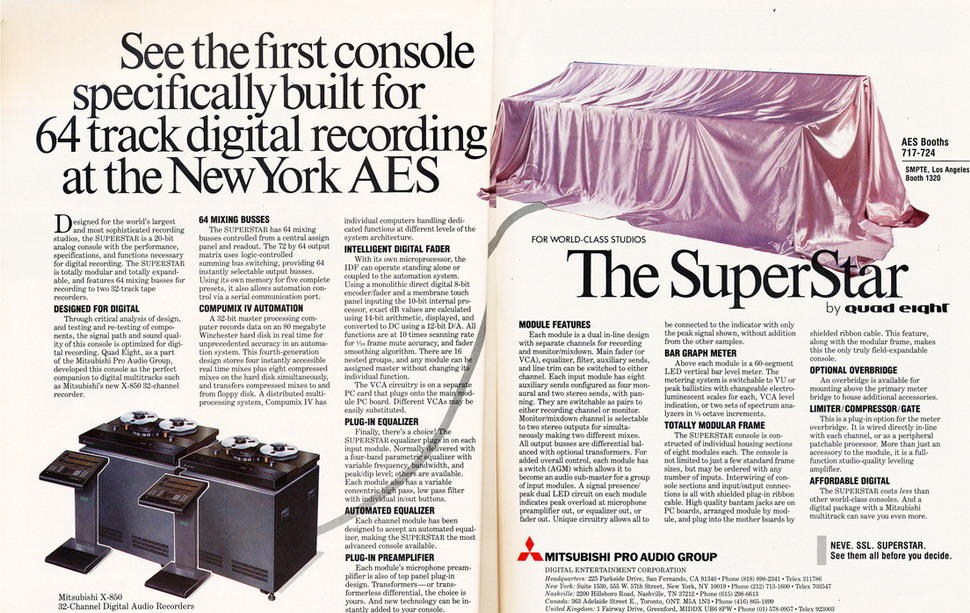

The X-850 has also become the basic tool in many of the most important studios. Do you remember the Brothers in Arms album and the confusion accompanying it? Located on one of the Caribbean islands, Montserrat Studios were heavily damaged by Hurricane Hugo in 1989 and most of the tapes stored there were destroyed. However, before this happened, in 1986 it was renovated and offered the following accompanying equipment description:

The recently refurbished studio with a 60-channel SSL automated console and TR, and 12 fully integrated Rupert Neve channels with Focusrite, two 32-track Mitsubishi X-850 digital machines and a 24-track Studer A800. Digital mix for two Mitsubishi X-86.

Billboard Aug. 9th 1986

There were many such places, but not all are remembered today. It is known, for example, that Peter Gabriel's Us album was recorded on Mitsubishi X-850 tape recorders in 1989, in a hybrid combination with the Studer A-820 tape recorder (recording director: Ian Copper, Townhouse).

Advertising photo with Kim Wilde, standing next to X-880, the photo is from 1989

Also known is an advertising picture of Kim Wilde, standing next to the complete X-880 system, and her album Close (1988) was created using the X-850 model. The same tape recorder was used to record individual tracks of such artists as: Tracy Chapman (Fast Car, more HERE, accessed: 11.05.2020), or Don't Worry, Be Happy by Bobby McFerrin (more HERE, accessed: 11.05.2020).

ECM

One of the most important places and one of the most important record labels that brilliantly mastered digital recording with Mitsubishi tape recorders was the Rainbow Studio, owned by Jan Erik Kongshaug (1944-2019), and the ECM.

In 1984, Jan Erik, together with a small group of enthusiasts, built his own recording studio in one of Oslo's districts, which he called Rainbow Studio. In 2012, he said in an interview for Tape Op magazine:

I've been working with digital recorders since 1986—first it was a 32-track Mitsubishi machine, then with a 48-track Sony machine and since about 1998 I've been using the Pro Tools. But I never mix the signal internally on a digital workstation such as Pro Tools or Logic. I like mixing on the console.

The German magazine nordische-musik.de describes this system in detail. Since 1986, the studio had the 32-track Mitsubishi X-850 tape recorder for multi-track recordings, as well as the X-86 as a mastering tape recorder. In 1990, Jan Erik bought a Sony PCM 3348 HR 48-track tape recorder, which gave him the ability to record a 24-bit signal. In addition, they had on hand analogue tape recorders—a 24-track Lyrec machine (a rarity) and stereo ones—Otari MTR-10 and MCI JH-110.

STRATEGIES

When the X-80, then X-800 and X-86 entered the market, there were no large digital mixers on available. There were small mixers of this type, but with up to eight channels. Digital systems were incompatible with each other, so Sony tape recorders did not work with Mitsubishi tape recorders and vice versa. Each company offered its own signal transmission protocol. We had to wait for a chance to complete a digital system consisting of a multi-track tape recorder, a mixer and stereo digital tape recorder. And even when companies finally offered suitable mixing consoles, hardly anyone benefited from this solution. The largest recording studios were dominated by analog mixers of two companies - Solid State Logic (SSL) and Neve.

Direct-to-two-track

Therefore, each studio has developed its own procedures, depending on the experience of their sound engineers, their predilections and belief in a given technology. Initially, mastering tape recorders X-80 and X-86 were used in analogue systems as—just—mastering tape recorders. Sound engineers thus avoided quality degradation that could happen when copying a glued together master tape to a production master tape, that was sent to pressing plants around the world.

You could use them in a different way—recording material directly to two tracks. DMP started to do it early, but soon others joined them. This type of discs were released, for example, by Blue Note, although they did not always inform about it in the description of particular disc. In later years (1990s), these tape recorders were also used as mastering ones in projects related to material remastering. Company called Fantasy has prepared a lot of this type of recordings, by remastering the material digitally directly on the X-80. Pablo, CTI and others operated similarly at that time.

Digital-analog

In the case of multi-track tape recorders, there were even more possibilities. For example, Peter Gabriel's live album Live in Athens 1987, that was part of the "anniversary" box So, Kevin Killen and David Bottrill recorded on a rented tape recorder Mitsubishi X-800 and mixed them to two tracks, but using analogue process, on analog tape. Same was done with the album of Patricia Barber Cafe Blue, recorded on X-850 and mixed in analogue to ½" analog tape on Studer tape recorder.

Hybrid systems

Finally, there is a group of albums that use a "hybrid" recording system—analog-digital. This was the case with the Pink Floyd album mentioned above—the percussion was recorded on a 24-track analogue tape recorder and mixed to two tracks on a digital tape recorder. Other instruments were already recorded directly to the digital tape, so one could copy tracks without any losses in quality. Although today it's a standard, every DAW system offers it, it was a state-of-the-art technology at the time. Yet another method was used when recording a Mark Hollis album. The whole band was recorded on two analogue tracks, then they were copied to a digital tape recorder and supplemented with subsequent tracks with instruments, vocals etc. And finally mixed again (in analogue system) to an analogue tape.

So it's hard to talk about one "sonic signature" of Mitsubishi devices—more depended on how they were used. The big problem was that the sound engineers operating them were just learning what a digital signal is and what to do to make the best use of it. Also mastering specialists cutting varnish in the pressing plants had minimal experience with the digital recordings. All this means that the discs recorded using Mitsubishi devices are very uneven. The best are DMP recordings and those the analogue technology was also used for.

SOUND

Below you will find a selection of several recordings, from different years and made using different technologies, by different sound engineers. I will try to briefly describe the way in which a given disc was made, and then I will listen to it, indicating the most important features of a given recording. Due to restrictions related to coronavirus (meaning: delays in deliveries and even some of them getting lost), not all discs arrived on time. As soon as they arrive, I will prepare an appropriate "follow-up" to complete the article.

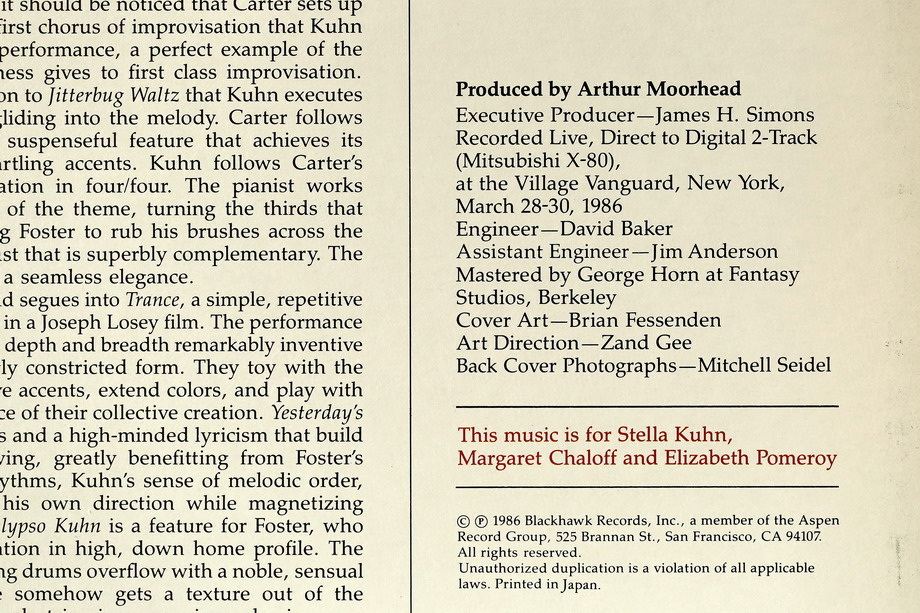

STEVE KUHN TRIO Life's magic. Blackhawk Records BKH 522, LP 1986

Life's magic was one of the first albums released by Blackhawk Records, founded in 1986 by Herb Wong. The album featured following musicians: Ron Carter (double bass), Al Foster (drums) and Steve Kuhn (piano). The material is a compilation of three consecutive evenings during which the trio played in the Village Vanguard. Recording was done by DAVID BAKER - from 1975 he was the chief sound engineers at the club. He also worked for the Japanese Eastwind label and collaborated with: ECM, Enja, Blue Note, Atlantic, Verve, Black Saint, Soul Note, and Amulet. The material for the Life's magic was recorded directly on two tracks using the X-80 tape deck.

Sound

The sound surprised me with its smoothness. Most of the early digital recordings, above all those available on CDs, were accused of graininess, brightness, and "glassiness" of the treble. And usually it was true. In retrospect, however, we understand that this was a problem of early CD players, not discs and recordings as such. On the other hand, LPs recorded digitally, if they contained a good recording and were properly produced, could surprise with their quality.

Like the disc Life's magic, which sounds fluid, smooth, pleasant. The sound attack is not sharp and the sound is not bright. I would even say that it is smoother than many analog recordings. I played the disc on the Air Force III turntable with the SAT LM-09 tonearm and two cartridges—My Sonic Lab Signature Platinum and Miyajima Lab Destiny, which probably benefited this recording. It "extracted" that smoothness from it. But also brilliantly presented outstanding dynamics, mainly the micro-dynamics, of this sound. The attack is very fast here, which gave the kick drum an amazing naturalness and I could almost heard the leather on it.

The problem that also repeated during the following listening session was a raised tonal balance—the main actor is the midrange here. The treble is brilliant in its vibrancy and natural decay, but the bass is too light. It seemed to me that the producers were afraid to emphasize it so as not to distort the recording (and in the case of digital recordings it is the death of a signal). Or as if they did not know this medium well enough to correct it during mastering and cutting the varnish.

However, it is a very natural sound, because it is dynamic, clean and fast. Just listen to the applause accompanying this "live" recording to see what I mean.

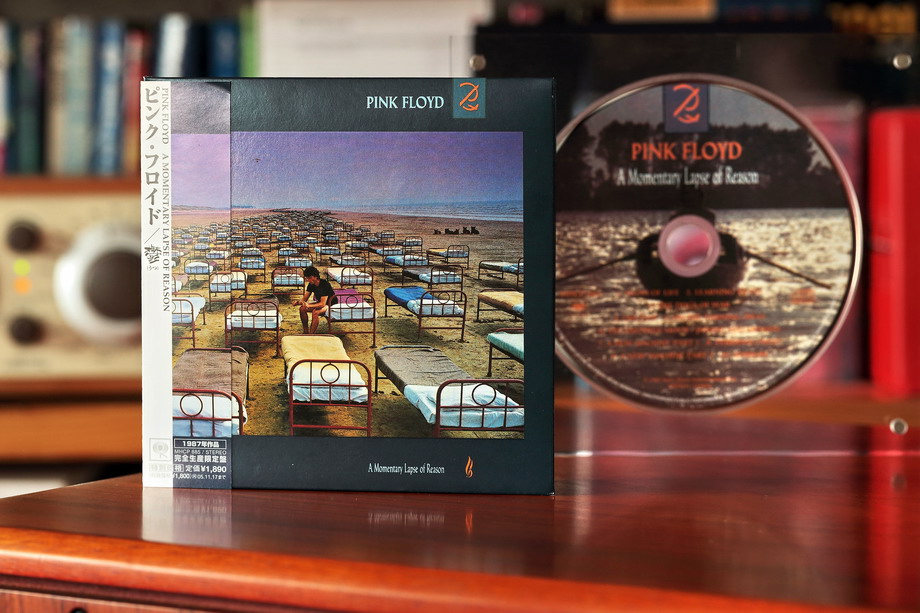

PINK FLOYD, A Momentary Lapse Of Reason. EMI/Sony Records Int'l MHCP 685, Compact Disc 1987/2005

A Momentary Lapse Of Reason from 1987 is the first Pink Floyd album recorded without Roger Waters, the band's longtime leader. The only permanent members of the band - which then fought the legal battle for the name—were Richard Gilmour, as the new leader (guitar, singing, keyboards, sequencer), and Nick Mason (drums, sound effects). Richard Wright also took part in the work on the album, but only as a session musician. Additionally one can also hear Tony Levin's bass and Chapman stick.

The album was recorded mainly on the Astoria residential boat belonging to Gilmour, that was adapted for the recording studio, and sessions lasted from November 1986 to March 1987. Additional tracks and mix were made in many other places. For us it is important that the drums - both Mason's, electronic drums (!) and three other drummers, were recorded on an analog, 24-track Studer tape recorder, and the remaining tracks on a digital tape recorder.

The album was released on September 7th 1987, and its sound engineer was ANDY JACKSON. He began working with Pink Floyd in the 1980s by assisting in recording of the album The Wall. In addition to A Momentary..., he is also responsible for the sound of the Division Bell. For the album we're talking about, he was nominated in 1988 for a Grammy Award.

Sound

Today, almost no one remembers that this album was made using digital tape recorders. Although its sound is more open than earlier Pink Floyd recordings, on the other hand the powerful, low tones coming in after the first minute of the opening recording Signs of Life would suggest an analogue tape recorder. And only in the sound of synthesizers one could hear a slight variation of tonality, which we already know from other discs recorded digitally on Mitsubishi (excluding the disc of Mark Hollis).

The Floyd album has an incredible momentum and opens up a huge panorama for us. It seems that in its case sound engineers have mastered the tools better, I mean the digital tape recorders. Probably also using a "hybrid" recording method help, because Nick Mason's drums have momentum and are not at all bright. I would even say they have a flat attack. Interestingly, they also have a slightly "dirty" sound, just like in analog recordings. The only downside are the sibilants not quite eliminated from Gilmour's voice.

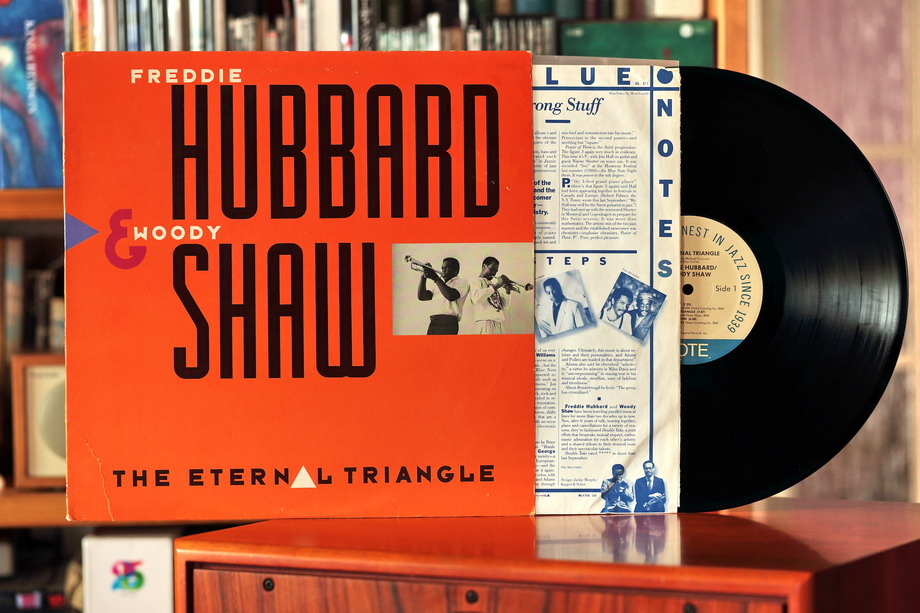

FREDDIE HUBBARD & WOODY SHAW, The Eternal Triangle. Blue Note B1-48017, LP 1988

1988 saw a decline of vinyl records—the CD "ruled" and publishers demanded DDD recordings. The Blue Note also headed in this direction. However, before the studios cooperating with the record label switched to DAW (computer) systems, Blue Note prepared several CDs using other methods. In their catalog, therefore, we can find several discs from the late 1980s digitally recorded directly on two tracks. Interestingly, they reached for the X-80 tape recorder, so for an "outdated" technology in the sense that there were newer tape recorders from this company available on the market, such as X-86 and X-86HS, as well as other, much cheaper systems. However, it seems that that its engineers preferred proven and trusted solutions.

On the The Eternal Triangle album in question, two brilliant jazzmen met for the last time: trumpet players Freddie Hubbard and Woody Shaw. In the late 1980s, they recorded three albums together, Time Speaks, Double Take and The Eternal Triangle, the last two of them were later released by Blue Note under the joint title The Freddie Hubbard and Woody Shaw Sessions. The Eternal Triangle was recorded and mastered by RUDY VAN GELDER in his studio at Englewood Cliffs.

Less than a year after the session for the album in question, almost blind, Shaw died. In turn, Hubbard, in the early 90s, started to have problems with the lips, which fatally affected his ability to play and ended his trumpeter carrier. Let me remind you that at the very end of his activity he still managed to play at the Warsaw Jazz Festival, where he recorded the Live at the Warsaw Jazz Festival album (Jazzmen 1992).

Sound

The Hubbard and Shaw disc is slightly different than the Life's magic by Steve Kuhn Trio. Its sound is no longer as smooth as the previous one, and in its sound a stronger emphasis was placed on high tones. But this is normal—the main actors are two trumpeters, the brass section also plays important role. But there is still no "brightness" or "shrill." I assume, and I'm probably not mistaken, that Van Gelder wanted to finally show the treble in all its purity, without any noise related problems. And he succeeded. It is not as resolving treble, or with such a good "weight" of cymbals as we usually get it with analog recordings, but it allows listener to feel the "weight" of the band playing in one room.

The other band's extreme is stronger than on the Steve Khun Trio's album, but it also isn't quite as rich. Generally the center of gravity is set in the middle of the band, rather in its upper part, which makes the sound of the album seem light and even bit shrill. The dynamics are very good again. There is no mass here, it is "here and now" presentation, so there is no tangibility either. But the sound image is really convincing. Except that other tools were used to achieve that than for analog recordings or good new digital ones (e.g. DSD).

However, by Blue Note and van Gelder's standards it is a step back. And, as it seems, it was caused not by the technology, but by lack of its understanding by the people who used it - whether during recording or when cutting the acetate.

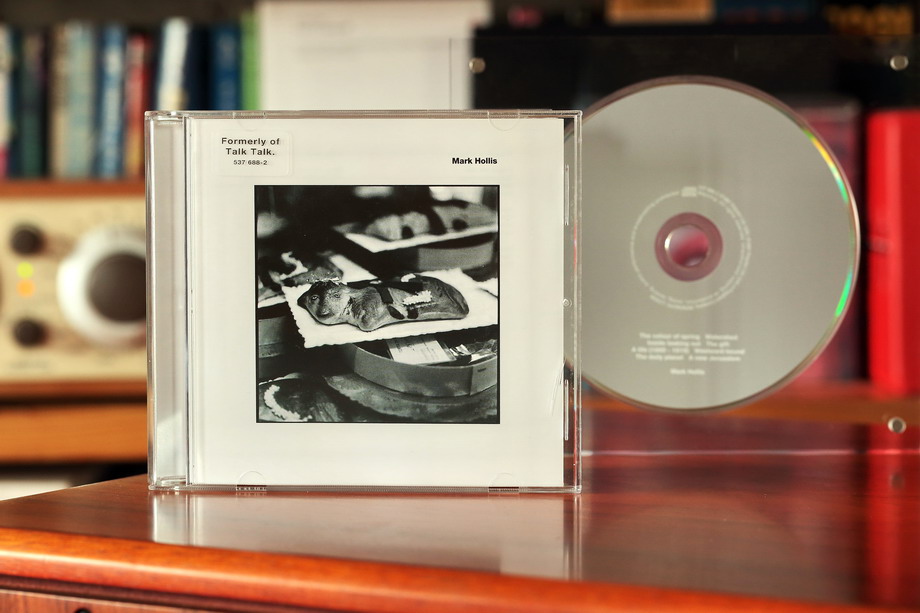

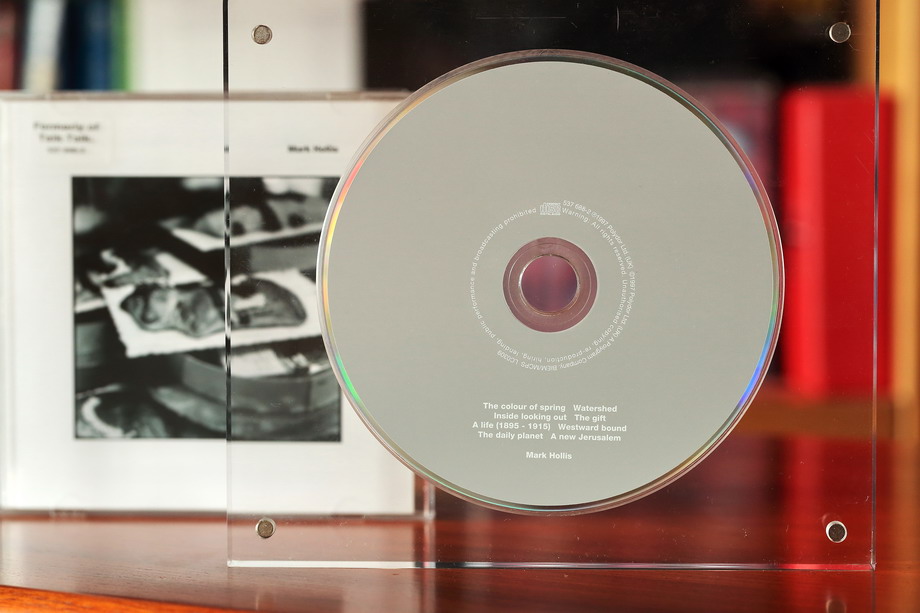

MARK HOLLIS, Mark Hollis. Polydor 537 688-2, CD 1988

Mark David Hollis (1955–2019) was an English musician and songwriter. He became famous along with the Talk Talk band. He released his only solo album seven years after the band was dissolved—the album was released by Polydor Records on January 26, 1998. It contained minimalist and stripped of all ornaments music, close to classical, experimental and jazz music. A recording session and, above all, the production process became legendary.

The basic instrumentation was recorded using two Neumann M49 microphones and Studer stereo analogue tape recorder. Only the Urei 1176 compressors operated in the path, with low compression levels. The whole band was set in a semi-circle in the studio and it was recorded the same way as jazz bands in the 1930s and 1940s. Then this stereo signal was copied (or only synchronized—it is not clear) with the Mitsubishi X-850 tape recorder, on which some tracks were added in a similar way as when using a sampler. As it reads in the musicians memoirs, it was a slow and tedious process. While mixing only spring reverb, EMT reverb and DDL's were used; the mix was made on AIR Lindhurst. PHILL BROWN was the man responsible for the recording.

Sound

If I were to point to the best, in my opinion, recording that Mitsubishi digital tape recorder participated in, it would be this particular album. Its sound is extremely natural, tangible and has a beautiful timbre. You can hear bass and brilliant treble, depth and fantastic foreground. The dynamics is flawless. There is a lot of noise in this recording, in the previous ones there was no noise at all, but it is a derivative of the original recording made on Studer's analog tape recorder. It also adds "flavor" to this album.

The disc surprises with dynamics during every listening session. It is emotionally credible, transporting us directly to the recording studio, with the musicians arranged in front of us in a circle. The most surprising is the purity of the high tones played by cymbals. It is placed in front of us, slightly away, that is in perspective. The tambourine, usually placed in the left channel, seems to have been recorded on the Mitsubishi tape recorder, just like the trumpet. But I can be wrong... It is a coherent whole with an amazing atmosphere.

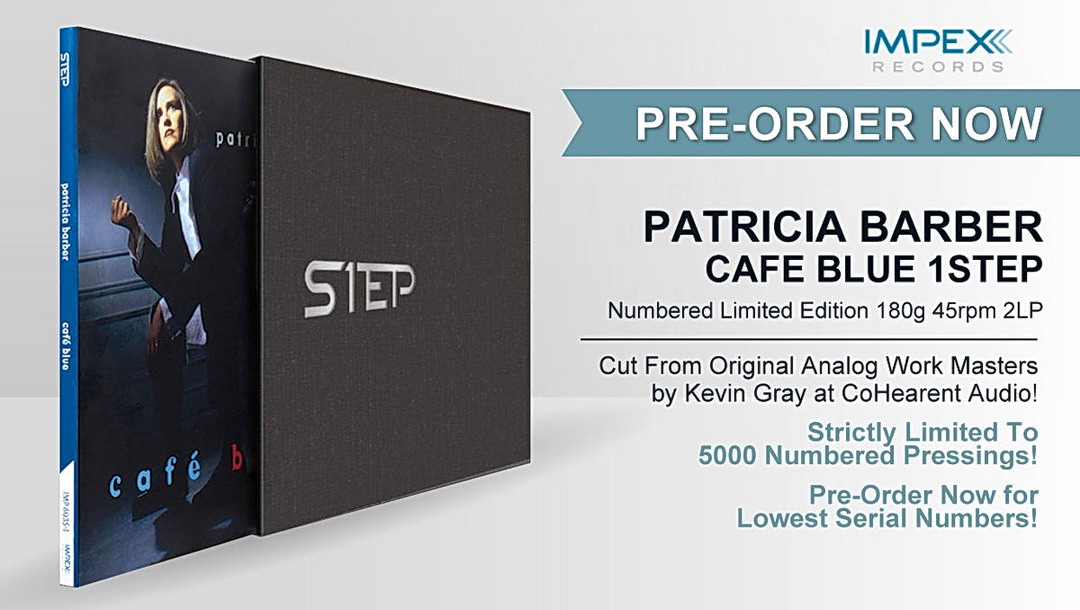

PATRICIA BARBER Café Blue. Premonition/First Impression Music FIM CD010, Gold HDCD 1994

Born in 1955 in the USA, the jazz and blues singer and pianist is one of the icons of the audiophile world. Her discs have been used for years during auditions, both at home and in public (exhibitions, shows). Most of her albums have been released on LPs and SACDs by Mobile Fidelity.

Cafe Blue is her third album and it was recorded with John McLean (guitar), Michael Arnopol (bass) and Mark Walker (drums). The sound engineer was JIM ANDERSON, and the producer was Michael Friedman; Gus Skinas was responsible for mastering. Anderson is one of the best known sound engineers today - he's a winner of ten Grammy Awards.

The material was fully recorded on a 32-track Mitsubishi cassette recorder (unfortunately it is not known which model) and mixed to analogue ½" analog tape. In 2016, its "raw" version "UN-mastered" was released, with so-called "Studio mix", i.e. without any additions. The new master was again prepared by Gus Skinas.

Sound

Everything I talked about on the occasion of LPs, to some extent returns with recordings from the Patricia Barber album. Its sound impressed me with the incredible clarity and richness of the vocals. This is for songs such as "Romnesque" or for just 57 seconds long "Wood is a Pleasant Thing to Think About" people are changing their systems, buying more and more expensive devices, trying to get even closer to the "truth." And this is because the sound is clear—it comes to mind first. But it also has a huge scale—the soundstage is huge.

Due to the fact that the digital material was mixed to analogue tape, Impex could write in the advertisement of the top 1 Step version: "Cut From Analog Work Masters"

Unlike previous recordings, this album has a lower tonal balance. Which does not mean that is actually low. It is still the midrange and its upper part that is most important, but the kick drum has a nice kick too. I heard there similar modifications as with the discs of Steve Khun Trio and the Freddie Hubbard & Woody Shaw duo. The thing is that the lowest bass is not very powerful, but the attack of the double bass and the drums are fantastic and they give the mass to the whole recording. Let me say that analogue recordings can rarely show such a thing, if at all—it's one of the features that put digital recordings from that time in a good light. Unfortunately, I can't find it in contemporary hard disk recordings.

IF EVERYTHING WAS SO GREAT, WHY DOES NO ONE WANT TO REMEMBER IT?

Mitsubishi tape recorders were the ultimate achievement of audio technology, both in terms of mechanical and electronic design. Designed by an audiophile-engineer, backed by the huge funds of a large corporation, they still surprise with brilliant sound today. The stereo versions offered the sound engineers something that no other digital tape recorders could—the ability to edit the material by simply cutting and gluing the tape back together, just like in the case of analogue tape recorders.

It is also important that the quality of these devices allowed for durable and precise recording. In comparison, all other mastering systems—like U-matic, CD-R, as well as DAT (Digital Audio Tape) were just remnants of former splendor. The only system of this type that could compare with Mitsubishi devices was the Sony's magneto-optical disc (MO), which was used in XRCD remasters.

So why was it so quickly forgotten?

The first reason was the fact of Mitsubishi's withdrawal from ProDigi format. They left the studios, which spent a lot of money on this equipment, without technical support. And Mitsubishi tape recorders often broke down. Thomas Bårdsen, head of the audio department at the National Library of Norway, described it well when he spoke about his efforts to copy library collections onto digital media:

The first stereo machine was the Mitsubishi X-80, appearing in Norway as early as 1981. For servicing and upgrades, it had to be shipped back to the factory in Japan. Certain upgrades meaning older tapes would no longer play. Only 200 machines were ever built, and Mitsubishi never got round and made a proper service manual. Even in their prime years, servicing was quite a challenge.

Digital Music Production MK I, www.dpconline.org, accessed on: 12.05.2020

The author ends the text by recalling an advertisement from November 1981, which shows a photo of the X-80 model that in January of the following year it was no longer produced and the 1986 X-86 model was not compatible with it.

The library stores over 1600 ProDigi and DASH tapes in 15 different configurations. Because lack of compatibility not only between the tape recorders of competitors, but even within a given company was another reason for "forgetting" it. In the case of analogue tape recorders, you could record a tape on one model, mix it on another, and master it on yet another—they were all (generally speaking) compatible. This was never the case with digital reel tape recorders. But the most important thing is that soon everyone became passionate about computer systems, where editing material was much easier than with reel-to-reel tape recorders.

CONCLUSION

John Goldstraw, technical manager at London Metropolis, where two 32-track Mitsubishi tape recorders worked in 1992, told Billboard that he liked the ProDigi system, and that the Otari DTR900II tape recorders are one of the best digital tape recorders in the world (Mitsubishi Ceasing Pro-Digi Sales). What's more, leaving the digital recording in the hands of one company—he meant Sony and the DASH system—is dangerous for the industry.

Goldstraw did not know or did not want to know that the world of pro-audio and recording methods at the time he spoke these words had already been changed forever and would never be the same. The reason for the changes were the inexpensive RADAR hard disk systems, as well as the inexpensive ADAT digital tape recorders, and the lead was soon taken over by DAW (Digital Audio Workstation—Digital Audio Workstation—for example the popular Pro Tools). But this is a completely different story. Many believe it is its dark side.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- "Richard L Hess—Audio Tape Restoration Tips & Notes," Instrumentation, richardhess.com HERE, accessed on: 19.03.2020

- Mitsubishi Bows Digital Units, Billboard June 12th 1982

- High Density Digital Recording, ed. Ford Kalil, Nasa Reference Publication 111, September 1985

- Sony PCM-1, www.thevintageknob.org HERE, accessed on: 07.04.2020

- Tape or disk and a manufacturer's solution, Studio Sound, March 1986, s. 114 (magazine in PDF format accessed HERE)

- en.wikipedia.org HERE, Digital recording, accessed on: 19.03.2020

- ntrs.nasa.gov HERE, accessed on: 07.04.2020

- www.sony.net HERE, accessed on: 19.03.2020

- BARRY FOX, Bits of sound give a better beat, New Scientist, No. 6, August 1981

- CHRISTOPH MEINEL, HARALD SACK, Digital Communication: Communication, Multimedia, Security, Heidelberg 2014

- HANNA JAMES, The promises of Sony PCM U-matic 1600, My Library Cosmos HERE 2017; accessed on: 07.04.2020

- JOE CLERKIN, Digital Aids The Video Stars, www.muzines.co.uk HERE, accessed on: 0719.03.2020

- JONATHAN SAXON, Jan Erik Kongshaug: ECM Records, Pat Metheny, Jan Garbarek, tapeop.com HERE, Sep/Oct 2012, accessed on: 12.05.2020

- MARVIN CAMRAS, Magnetic Recording Handbook, New York 1988

- SAMANTHA BENNETT, Modern Records, Maverick Methods. Technology and Process in Popular Music Record Production 1978-2000, Bloomsbury Academic, Londyn. New York 2019

- STEVEN DUPLER, Digital over Analog in Two Years, Billboard, 9 August 1986

- STEVEN E. SCHOENHERR, Tom Stockham and Digital Audio Recording, Audio Engineering Society

- THOMAS FINE, The Dawn of Commercial Digital Recording, ARSC Journal, Volume 39, No. 1, Spring 2008

- THOMAS BÅRDSEN, Digital Music Production MK I, www.dpconline.org HERE, accessed on: 12.05.2020

- ZENON SCHOEPE, Mitsubishi Ceasing Pro-Digi Sales Marks 1st Stage Of Pro-Audio-Biz Pullout, Billboard, Nov. 28th 1992

Text: Wojciech Pacuła

Images: press materials: Wojciech Pacuła