Everything you want to know about the recording of Blue Train's behind-the-scenes and which of the digital reissues of this jazz masterpiece are the best.

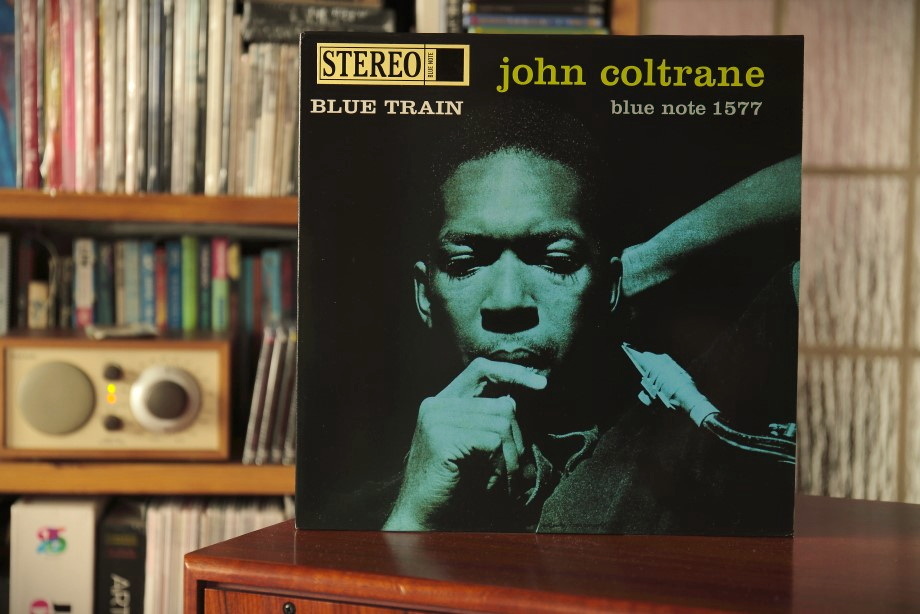

On September 15th 1957, John Coltrane walked into Rudy Van Gelder's studio in Hackensack and recorded a masterpiece album: Blue Train. It was the only album by a saxophone leader recorded for Blue Note Records.

To celebrate the 65th anniversary of Blue Train, Blue Note presents it in the latest Kevin Gray remaster and Joe Harley production, both in mono and stereo versions; it was released as part of the "Tone Poet" series. For the first time ever, we got a version with seven bonus tracks, none of which had previously been released on vinyl, and four of them not at all, in any format.

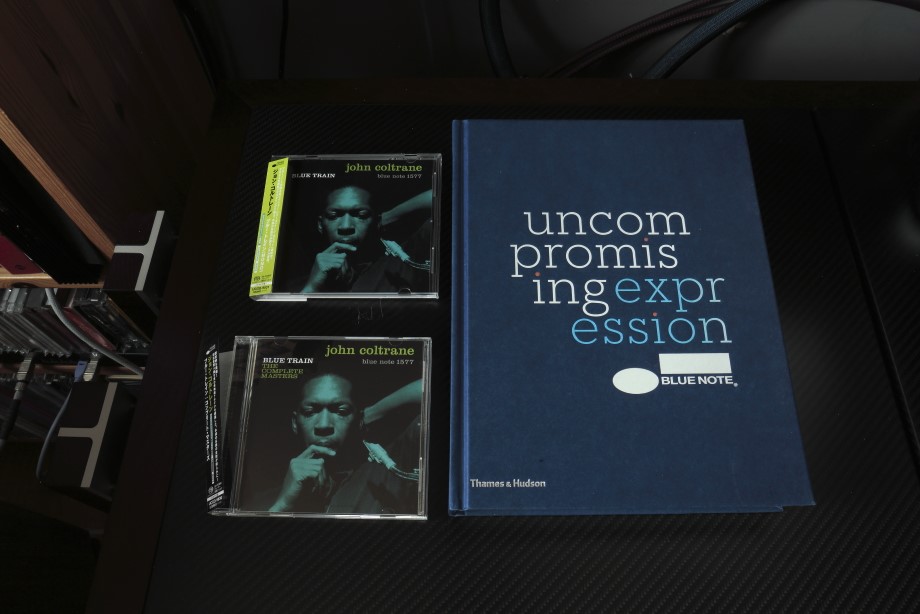

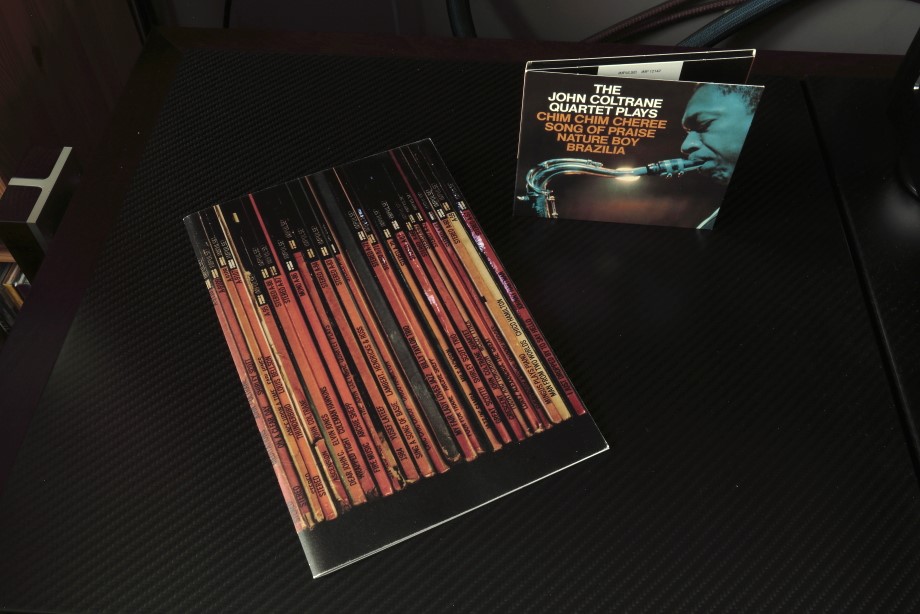

Two latest remasters on SHM-SACD, mono (top one) and stereo

This version is officially titled Blue Train: The Complete Masters. LP and CD discs hit the stores—the former as single-disc and double-disc issue. Also part of this edition are previously unpublished photos by Francis Wolff and an essay by Ashley Kahn an expert on Coltrane lore. This is a good time to take a look at all major digital reissues of this title. It will give us an opportunity to talk about different types of releases, formats and versions, from Compact Disc, through Copy Controlled Disc, Gold-CD and Super Audio CD, to UHQCD, SHM-CD, Platinum SHM-CD, and SHM-SACD.

Article has been divided into two parts. In the first one, we will introduce the musician, talk about the sound engineer Rudy Van Gelder and reveal some secrets of his trade-craft. We will also take a look behind the scenes of the recording session from which the material for the Blue Train album comes from. In the second part, we will discuss the fourteen most important releases of this album on digital discs, culminating in the new 2022 remaster on SHM-SACDs, and we will point out the best ones.

John Coltrane

Born September 23rd 1926 John William Coltrane was an American musician, saxophonist, one of the most important jazz figures. After graduating from high school, he moved to Philadelphia to study music. Originally playing bebop and hard bop, he was one of the pioneers that created modal jazz, and then free jazz and avant-garde jazz.

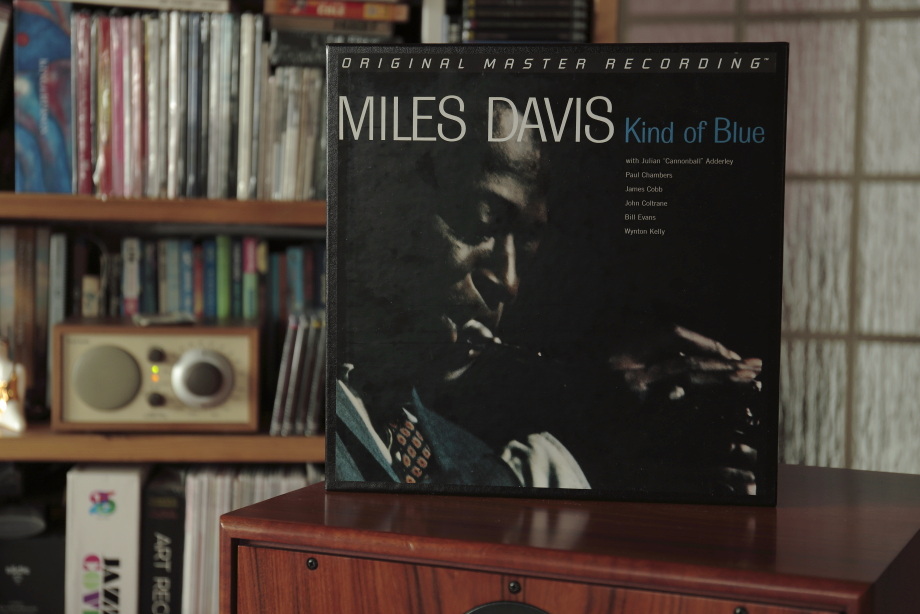

He has recorded over fifty albums, both solo and as a sideman, but his position was solidified by playing in bands with Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk. He met Davis in 1955. In a quintet called the "First Great Quintet," with Davis, Red Garland, Paul Chambers and Philly Joe Jones, he recorded albums entitled Cookin', Relaxin', Workin' and Steamin'. The quintet was soon disbanded, largely due to Coltrane's heroin addiction.

One of Coltrane's greatest works, Giant Steps, released by Atlantic Records

In the second half of 1957, the saxophonist was a resident of the New York's club Five Spot Café, where he played with Thelonious Monk. During this time, he was asked by Alfred Lion, head of the Blue Note label, to record a solo album for him. The following January, Miles Davis readmitted him to his band, then a sextet. He remained a member until 1960, recording with him such masterpieces as Milestones (1958) and Kind of Blue (1959).

At the end of this period, Coltrane recorded his next solo masterpiece, Giant Steps, released in 1960 by Atlantic Records, the label Coltrane was working with at the time (HERE). The quartet he assembled at that time released the album My Favorite Things in 1961. This was the first time Coltrane played a soprano sax on an album, having previously played a tenor saxophone.

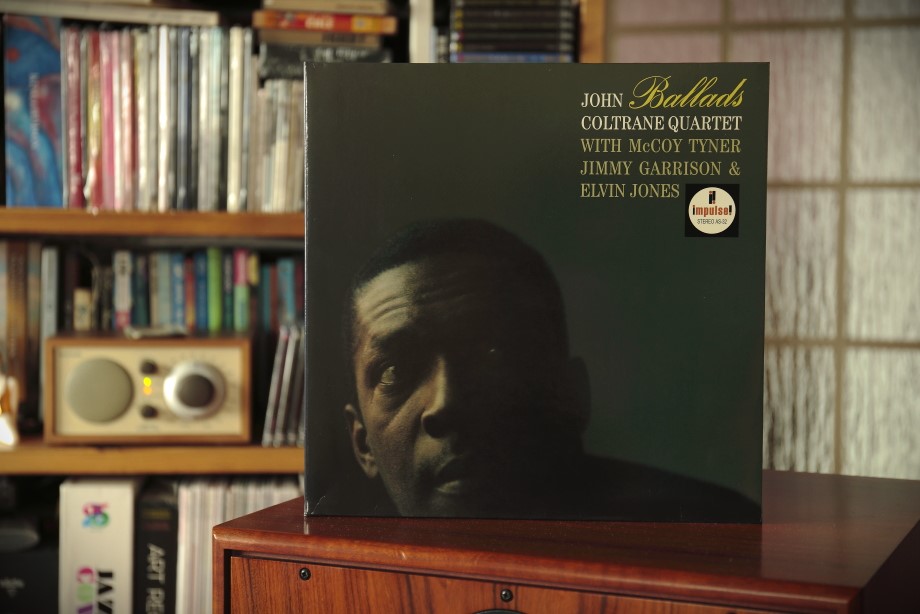

In May 1961 Atlantic buys Impulse! and since then Coltrane's albums were released with a distinctive stamp on the records. The years 1962 - 1965 are called the period of the Classical Quartet. This is when A Love Supreme (1965) is created. In July of the same year, John enters Van Gelder's studio with, among others, Pharaoh Sanders to record a 38-minute solo suite of young avant-garde jazz musicians for the Ascension.

In the same year, the saxophonist began experimenting with LSD and founded the so-called The Second Quartet with whom he recorded several live albums. John Coltrane died of cancer at the age of 40 on July 17th 1967.

There wouldn't be the characteristic Coltrane sound if it weren't for personal musical and spiritual explorations, but also if it wasn't for Rudy Van Gelder, a sound and mastering engineer and one of the most important innovators of this profession.

Rudy Van Gelder

Rudy Van Gelder passed away unexpectedly in 2016. He had been ill for several years, but there was no sign of his passing soon. Optometrist by trade, active in the profession long after his name became synonymous with high-quality sound, he developed a set of techniques that allowed his recordings for labels such as Savoy Records, Prestige Records, Impulse!, Verve, CTI, and Blue Note being considered exemplary in many cases.

However, he is known primarily for his work for Blue Note, for which he recorded almost all sessions in the years 1953 - 1967. He collaborated with "all the saints" of the jazz world, such as: John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Sonny Rollins, Art Blakey, Lee Morgan, Joe Henderson, Freddie Hubbard, Wayne Shorter, Horace Silver, Red Garland, Herbie Hancock, Alice Coltrane, Grant Green, and many, many others.

A man, one could say—from nowhere, outsider, without money and connections, operating outside the network of large studios, which was a sensation at the time; the time for independent studios will come only in the 1960s. Maureen Sickler, who currently manages the master's studio, when asked about what attracted musicians to him in the early stages of his career, said:

I think that many factors contributed to this. (…) Rudy always was one hundred percent dedicated to the mission of achieving the best possible sound for the musicians who came to him. It made them feel comfortable because they believed he would capture their music in the best possible way. He worked alone, keeping his overhead costs low. So it was attractive to labels and to the artists themselves. There was never a corporate mindset in his work, it was always an individual approach and full focus on the album he was about to record.

Barbie Bertisch, Heavy Sounds: Rudy Van Gelder Studio, Impulse! 60 Collector's Zine, p. 19.

He developed an interest in sound recording as a teenager, using a rather primitive 78 rpm Home Recordo recorder. The sound was captured by a tube and immediately transferred to a blank cardboard disk covered with lacquer. He was also a radio amateur, and in high school he started building his own mixers and amplifiers. He played the trumpet in the school orchestra, but—as he says—he played "terribly." It turned out, however, that he had a knack for recording and in a furniture store owned by his friend's parents, he recorded both the orchestra in which he was supposed to play and other musicians.

His other passion, photography, influenced him to undertake optometry studies. It stayed with him for a long time - it is thanks to it that we know exactly what the stages of building his house and recording studio in Englewood Cliffs looked like. The breakthrough moment for him was a visit to the WCAU radio station, based in Philadelphia, where he studied. According to the author of Van Gelder's biography on the RVG Legacy website, he recalled this moment in many interviews, emphasizing its importance for his career choice: "Seeing engineers working on futuristic-looking hardware gave him a strong sense that this is where he wanted to be (HERE).

Credit for Miles Davis' masterpiece from 1959 has also be given to Coltrane

After college, Van Gelder moved to Hackensack, New Jersey and built a recording studio in his parents' house. He not only convinced them to record in their living room, but also to build a house around it. The salon, although large, had nothing to do with the contemporary recording studios of major labels. Almost without reverberation, this interior had "dry" acoustics. In order to master it, he developed several techniques that not only allowed him to deal with it, but also built his legend—the sound that is called "Van Gelder Sound."

We don't know everything, not everything is clear. The owner of the studio was almost obsessed with his choices and protecting his secrets. He came up with everything himself, he was the first to introduce many solutions to the studio. So he didn't want others to copy his solutions. What is interesting is that he willingly took advantage of such opportunities, watching others at work, and even asking a friend to smuggle a camera to the Capitol Records studio and take photos documenting the equipment used in them. As he later said, it was "Operation Navy SEAL" (Sickler).

The most important thing about what is described as "Van Gelder sound" is the intimate perspective from which we "see" the instruments. He achieved this by placing the microphones very close to the sound sources. Today it is a natural thing, but then it was almost a revolution. Jazz was still being recorded back then, just as classical music is recorded, i.e. with microphones placed away from the musicians. We don't know exactly what it looked like at Van Gelder's, although we know a lot of photos from recording sessions—the sound engineer moved the microphones for the photos.

Moreover, he had an extremely emotional relationship to microphones and recording equipment, because he chose everything himself and often co-designed it. He didn't have much money, so purchases had to be well thought out. In 1987, producer Alfred Lion said that Rudy had "top gear and was going to make better LPs." If there was any new, interesting piece of equipment on the market, “Rudy had to have it, no matter how much it cost. In this respect, he is still a pioneer and tries to be one step ahead of others" (Fox, p. 67). One of his most important devices was a tape recorder. The way he worked with it was the second factor, after the close positioning of the microphones, that defined the sound of his recordings.

The first projects created in his studio were made on 78 RPM acetals, and then on the amateur Presto PT-900 tape recorder. In June 1951, he bought one of the first tape recorders on the market—the monaural Ampex 300-C, costing $1600 (about $17,000 today). This was an unusual move for an independent sound engineer, as it was a huge amount of money he had to borrow from his parents. But that's exactly why he was such an attractive partner for recording labels—everything was top of the line with him. By the end of 1953, there were two more Ampex in his studio. He used them differently than usual, at least by the standards prevailing in recording studios at the time.

The thing is that he saturates the tape to the maximum using signal limiters. He didn't care that the VU-meter's arrow was constantly wandering into the red field, well beyond the "0 dB" mark. As long as he didn't hear obvious distortion, he maintained a high level of drive. Anyway, even if something was slightly distorted, he did not pay attention to it—that's why in many of his recordings some phrases are not entirely clean. The classical theory said that one should beware of this, which was cultivated primarily by classical music producers. In Poland, in the 1960s, the studios of Polskie Nagrania strictly adhered to it.

Released in 1963 by Impulse! The album Ballads was recorded by Rudy Van Gelder

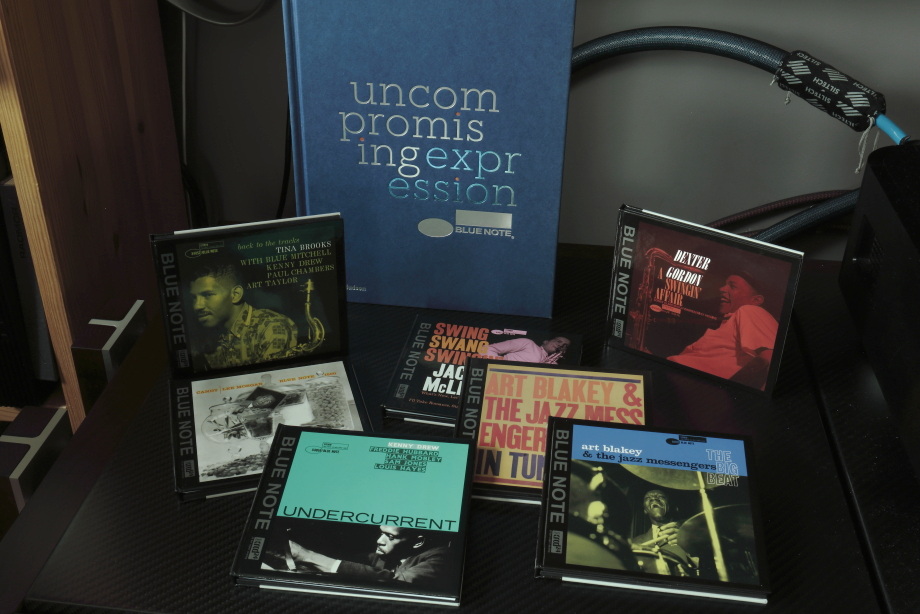

Percussion benefited most from this technique. As we read in the monograph entitled Blue Note: Uncompromising Expression, Van Gelder was a "recording master" of this instrument, "notoriously—the author writes—a difficult instrument to record, as any modern sound engineer will confirm." Tape saturation leads to mild compression that cannot be achieved with classic compressors. And Van Gelder liked to compress, which is confirmed by Joe Harley, the producer of the latest reissue of Blue Train, describing the process of its preparation.

This approach also resulted from Van Gelder's experience as a listener and a music lover. Producer Michael Cuscuna explained it this way:

Rudy loved the way the music sounded live - he would come home after a concert and feel that [his] recordings didn't really sound like a performance. He believed he could improve their sound […] He changed the way jazz music sounds on LPs by bringing them closer to the concert experience (Schaffer, 2010).

Perhaps it was a side effect of the sound engineer's pursuit of something else - to minimize noise. Because Van Gelder truly hated tape noise. And by raising the average sound level, it automatically improved the signal-to-noise ratio. No wonder that as soon as digital recording devices appeared on the market, the hero of this story immediately bought them for himself, becoming an ardent advocate of this technique. Some of his statements are extremely surprising, if we know how perfect his analogue recordings sound. The Wikipedia entry ends the description of his career with a quote from the "Audio" magazine, he gave an interview for in 1995:

The biggest distorter is the LP itself. I've made thousands of LP masters. I used to make 17 a day, with two lathes going simultaneously, and I'm glad to see the LP go. As far as I'm concerned, good riddance. It was a constant battle to try to make that music sound the way it should. It was never any good. And if people don't like what they hear in digital, they should blame the engineer who did it. Blame the mastering house. Blame the mixing engineer. That's why some digital recordings sound terrible, and I'm not denying that they do, but don't blame the medium.

Wikipedia, en.WIKIPEDIA.org, accessed: 1.02.2023.

In the "digital" period, Rudy Van Gelder first bought a Sony U-matic PCM-1630 stereo mastering tape recorder, and then a Mitsubishi X-80 stereo reel-to-reel tape recorder, which he replaced in the 1990s with a Sony DASH PCM- 3402. Both of these devices were stereo machines, because the sound engineer believed that multi-track recordings work to the detriment of the music. And yet, the requirements of the market prevailed and in the 1970s he started recording music in multitrack on an analog tape recorder, and then bought a 24-channel Sony DASH PCM-3324 reel-to-reel digital tape recorder.

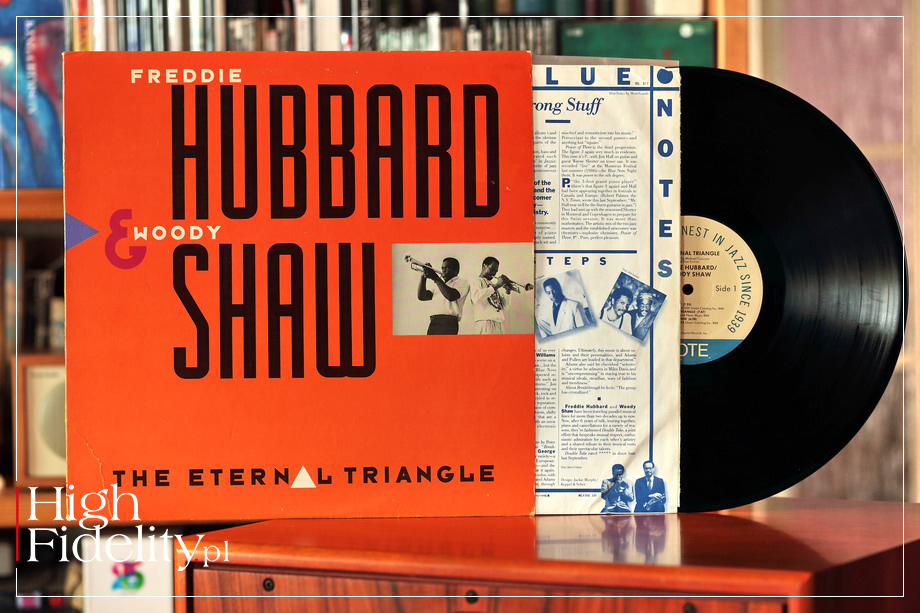

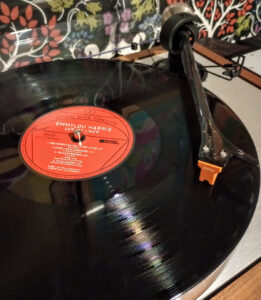

Opinions about the digital era in his work are divided, and I do not fully share his enthusiasm. Although I admire early digital recordings, including those made using the aforementioned Mitsubishi tape recorder, Van Gelder's "live" recordings using it are not entirely convincing to me. In the article about the ProDigi format, I reviewed the album by Freddie Hubbard and Woody Shaw entitled The Eternal Triangle. It was digitally recorded and digitally mastered by Rudy Van Gelder at his studio in Englewood Cliffs (more about ProDigi HERE).

Zin, which was released on the anniversary of the founding of Impulse! It is assumed that Coltrane "built" its brand

As I wrote then, the bass is too light on it, and the whole lacks the saturation that the sound engineer's albums had in the 1950s and 1960s. The explanation could possibly be something else. Rudy cut acetates himself, he had a top Scully cutter in his studio. So perhaps the problem lies with the LP itself, and not with the recording. It's just speculation, but with pretty solid foundations. In order to cut a digital recording, a signal had to be passed through a delay circuit—one signal was sent to the analog computer controlling the cutting, and the second (delayed) signal was sent to the cutting head after a while. And this may be the reason for particular sound of the mentioned album.

Be that as it may, Rudy Van Gelder remains one of the most important sound engineers, and few can match him, such as—recording for Prestige Records—Roy DuNann. His recordings arouse great respect, even if not everyone likes the way he recorded the piano—highly compressed, with microphones almost touching the strings. Van Gelder created his own, extremely distinctive sound he is associated with.

Almost everyone wanted to work with him - producers and musicians. Almost, because one of the few examples of lack of "compatibility" with the sound engineer was double bassist and composer Charles Mingus. As he told Downbeat magazine in 1960, the owner of the Englewood Cliffs studio was "changing the sound of the instruments" by positioning the microphones, putting his own vision ahead of the musicians'. "I saw," he said at the time," how he recorded Thad Jones and the way he positioned him at the microphone could change the whole sound that way. That's why I never go to him; it could ruin sound of my bass."

However, this is an isolated exception. There are many more of those who consider Rudy Van Gelder a genius. He earned this reputation with records such as John Coltrane's Blue Train, among others.

Blue Train

As we read in the Blue Note's promotional materials when asked in the 1960s in a radio interview about his favorite album, he participated in, Coltrane answered without hesitation: Blue Train. It's interesting because he recorded it right after he was fired from the Miles Davis' band due to his heroin addiction, and additionally he recorded it for the label where he released only this one title as a leader. So it could have been for him a kind of "souvenir" of worse times, and it became his favorite achievement. Billboard magazine wrote about the music on it:

A provocative element in a strong, modern idiom, noting above all the rousing continuity of Coltrane's solos. Clearly moved by the lively, creative rhythm—Paul Chambers, (Philly) Joe Jones, Kenny Drew, and trumpeter Lee Morgan and trombonist Curtis Fuller also had their best performances.

The material for the album was recorded in one day, on September 15th 1957, at Rudy Van Gelder's studio in Hackensack, New Jersey, and was released a year later—first as a mono LP, then as stereo. The move to a new purpose-built studio in the nearby town of Englewood Cliffs did not take place until June 1959. The album was released by Blue Note Records.

Alfred Lion met the inventiveness of Coltrane, who received permission to choose the accompanying musicians, which he willingly took advantage of, completing a wind section composed, unusually, of as many as three wind instruments. Lee Morgan played on trumpet, Curtis Fuller on trombone, Kenny Drew on piano, Paul Chambers on double bass and Philly "Joe" Jones on drums. John Coltrane worked with Lee Morgan only twice: first during the sessions for Johnny Griffin on April 6th and 17th 1957 (A Blowing Session), and a few months later on the album in question. Morgan was only 19 at the time and Fuller was 25; a year later they both became members of Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers.

Selected Blue Note albums produced by Rudy Van Gelder, remastered for XRCD24 issue

Kenny Drew played with Coltrane on March 2nd 1956, on the Chamber's Music album, which featured the same rhythm section as on Blue Train (Drew, Chambers & Jones) with Coltrane's saxophone as the only solo instrument. Coltrane's professional association with Chambers and Jones began when the three were members of Miles Davis' first great quintet (with pianist Red Garland as the fifth member). After the release of the album in question, they never recorded anything together again.

Unusually, the musicians were paid by the label to practice before entering the studio; Coltrane, along with Thelonious Monk, was a member of a band playing at the Five Spot Café club at the time. So they went into the studio prepared. And this studio, as we said before, was Van Gelder's parents' living room. It was small, so the sound engineer placed the microphones very close to the instruments (element 1) and highly saturated the tape, and used a lot of compression (element 2). In the photos taken during the session by Francis Wolff you can see the microphone that Coltrane played into—it was Neumann U47. And this is the third piece of the puzzle that makes up the "Rudy Van Gelder sound."

MICROPHONES

To understand why this is such an important innovation, you need to take a look at what was going on in American studios in the 1940s and 1950s. At that time, US studios were equipped almost exclusively with domestic devices . It was similar with the British market, although there were Altec loudspeakers and Ampex tape recorders there. In the 1960s, these differences were so clear that one could talk about the "American" and "British" sound.

Americans benefited from the post-war economic boom, which saw companies such as Ampex, Altec and RCA dedicate large amounts of money to research and manufacturing of new music recording devices. These were quickly bought up by native recording studios. On the other hand, according to Howard Massey, the author of the The Great British Recording Studios monograph, until the 1960s almost all British labels had their own mixing consoles (p. 5). In Abbey Road (EMI) there were REED mixing consoles, in Decca studios a mixer designed by Roy Wallace, and in Philips Neumann, replaced only in 1966 by a transistor Neve mixer.

The differences between the two markets were also manifested in the design of cassette recorders, instruments, amplifiers and even microphones. American tape recorders used a correction curve called NAB, developed by the National Association of Broadcasters, and European - primarily Studer, but also BTR, EMI tape recorder—a curve called CCIR (Consultative Committee for International Radio, also known as IEC1). It was a German innovation from the 1950s, more recent than NAB. Later tape recorders offered switched values, but many engineers believe that NAB and CCIR differ not only in parameters, but also in sound.

Also in the case of microphones, the differences were more serious and did not concern only the appearance or functionality. Tony Visconti, producer of, for example, David Bowie and T. Rex albums in another Massey book entitled Behind the Glass Volume 1: Top Record Producers Tell how They Craft the Hits, says that British studios used mostly condenser microphones, characterized by stronger highs—implicitly: better ones.

In turn, the American studios were equipped with domestic microphones, primarily large, angular shaped, ribbon RCA-44 BR. The type of diaphragm was important, but perhaps something else mattered even more. The American microphones, due to their construction, worked with low output voltages, while the German ones—because this is what it is all about - with high ones. That's why US mixing consoles have high input sensitivity and European mixing consoles have low.

As long as everyone stuck to their "region", there was no problem with it. This came with the arrival in June 1948 of the Neumann U47 microphone. Van Gelder first saw it in 1951 while visiting Reeves Sound Studios in Manhattan. As the author of the biography of this sound engineer writes, it may have been the only such microphone in the United States (HERE, accessed: February 2, 2023).

Van Gelder immediately wrote to a friend stationed near Munich asking him to buy a unit for him. He did, but the microphone became the main one used for the recordings in Hackensack only from January 1953. And it was also used to record John Coltrane's saxophone. Initially marketed under the Telefunken brand, the U47 quickly became famous among producers and was bought by many studios in Great Water, including Columbia Records and Capitol Records.

Miles Davis, Musing Miles (1955), re-issue by Analogue Productions; photo presents Neumann U47 microphone

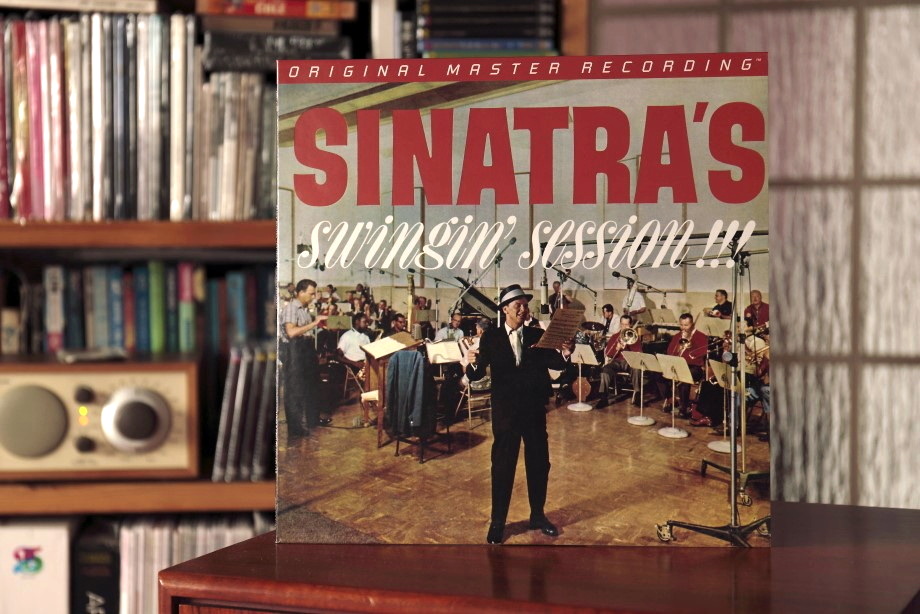

It has been immortalized on many album covers, for example Frank Sinatra's, and has also been used by Nat "King" Cole and other jazz greats. The tube type, originally with Telefunken tubes, with a large diaphragm, was perfect for this purpose. The author of Since Record Begin: EMI, The First 100 Years writes bluntly:

These [microphones] had gold-plated capsules and built-in amplifiers, and were invaluable in achieving optimal sound balance in recordings. They proved so good that they remain in daily use in Abbey Road studios to this day and are extremely desirable on the secondary market (p. 152).

The producer of the Blue Note albums, however, faced a problem related to the aforementioned high output level of the microphone. In large studios, Neumann was mainly used to record the orchestra, standing quite far from the instruments. The output level obtained from it was therefore relatively low. When a vocalist sang to it, special faders had to be used before entering the mixer. For Van Gelder, this was unacceptable. For one, in his microphone technique they were placed very close to the instruments, and two, he believed that attenuating a high signal in order to amplify it later made no sense.

So the only way out was to replace the entire mixer. As he said in an interview for the "Tape Op" magazine, he built the first device of this type himself, and only the next Altec 230B mixer, which was designed for a radio studio, was bought by him, serving him between 1954 and 1956. For U47, however, he needed something completely different. His good friend, Fairchild engineer Rein Narma, came to his aid.

Sinatra's Swingin' Session!!! from 1961 – Sinatra with Neumann U47 in the forefront, there is also another one in the back in front of the brass section

Van Gelder found out what kind of mixer he would like to have after looking at photos secretly taken for him in the control room of Capitol Records. Do you remember Operation "Navy SEALS?" It was its aftermath. Narma made a tube console himself, similar to the one he saw in the photo, but with an input circuit for high-level microphones (condenser). It featured ten inputs, each with three tone control points, an echo camera output and an input circuit with 20 dB gain.

A beautiful, large, with knobs instead of sliders, the mixing console arrived at the studio in January 1957, just early enough to warm up well and get settled before the Blue Train session. After moving to the Englewood Cliffs studio, the mixer went there as well.

SPACE

So there is close positioning of the microphones in relation to the sound sources, high saturation of the tape in the tape recorder and the use of signal limiters, the U47 high-level microphone and a mixer built for it. There was one more thing that was unusual for the "Van Gelder sound:" space.

The studio in his parents' house was really small (you can find a virtual tour of his studio on YT HERE, accessed: February 2nd 2023). Although ten people from Gil Evans's orchestra fit there, it was a challenge, as the owner of the studio himself said. The small room meant there was almost no natural reverb. And Van Gelder loved a large soundstage—deep in monophonic recordings, and extra wide in stereo ones. If we add two and two, i.e. what we are talking about, to the proximity of instruments and microphones, which eliminates reverberation to almost zero, and the pursuit of a sound with a large scale and power, we will understand that he had to use the reverberation device.

The Eternal Triangle by Freddy Hubbard and Woody Shaw (1987), a digital recording by Rudy Van Gelder

The name "reverberation camera" I used earlier came from the fact that the largest reverberation devices were built in the form of special rooms (Latin camera means room) in which microphones were placed on one side and speakers on the other. The larger the room, the longer the reverberation. All the major labels had their echo chambers, and the most important ones, such as those at Capitol Records and Columbia Records, achieved "cult" status.

At home, Van Gelder could not afford such extravagance. His early professional recordings, from 1951-1954, are characterized by a dry sound and are "squeezed", they lack development. One of the first recordings recorded there and broadcast on the radio was a session with organist Joe Mooney, released by Carousel; it was still a 78 rpm acetate recording. An album recorded on a tape recorder, but still without echo, was Progressive Al Cohn by Al Cohn Quintet, released in 1953 by Progressive Records.

Van Gelder was aware of the limitations of his workplace. He was also a perfectionist, in love—as we said—with the sound of jazz bands playing live. In the mid-1950s, tape-based delay circuits (see Elvis Presley and Heartbreak Hotel) and spring reverbs became fashionable. I remember working in the early 1990s at the Maszkaron Satire Theater in Kraków and having an old mixer from the American company Peavey at my disposal. It had a reverb installed that sounded just awful, as if the recording was suspended on a long rubber band.

Van Gelder thought similarly, which is why he never reached for these solutions. Fortunately for him and for us, music consumers, in 1957 a solution from another, after Neumann, German company appeared on the market. Dr. Walter Kuhl, working at the Hamburg-based Institute For Broadcasting Technology, invented an electro-mechanical reverberation device, the so-called plate reverb. It entered the market under the EMT brand—Elektro-Mess-Technik—and received the number 140; it was a mono device, for the stereo version we had to wait until 1961. It was one of the most important developments of the decade, and soon this reverb found its way into all good studios. Interestingly, Abbey Road found them later than Van Gelder.

The sound engineer received his unit with serial number 040 right after the device was released to the market and since the end of 1957 all recordings made by him have this characteristic sound. Interestingly, when Van Gelder bought a second reverb in 1962, it turned out that it sounded different from the original. The preserved correspondence with Kuhl shows that the sound engineer sent him several recordings with both reverberation plates for checking.

The inventor agreed with the thesis about their difference, but neither he nor his team could say why. What's more, it sounded completely different than all the others produced by EMT. The Blue Train album was recorded with the only such sounding reverb machine in the world. By the way, having two huge boxes (each weighing 275 kg) living in Englewood Cliffs, he had them placed vertically against the wall in the bedroom.

MASTERING

Finally, the mastering side should be mentioned. Rudy was such a "handy" man for recording labels because he did everything himself - from recording, through mastering, to cutting lacquer. For the latter, he used a Scully 60 cutter, which at the time cost a whopping $8,500 (in 2020, it would be around $80,000). The machine started working in 1955, and in 1962 a second one joined it.

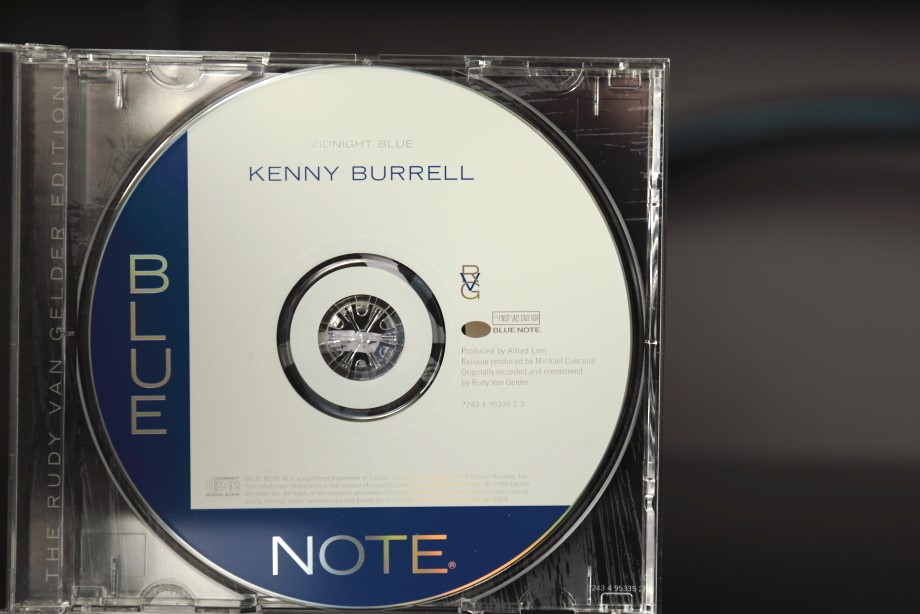

From 1999 Van Gelder started to remaster all his recordings made for Blue Note—they were releases as the RVG Edition series

Together with the cutter, he bought an amplifier for the stylus, Grampian B1/AGU, made in UK, also used by the British Broadcasting Corporation. As the author of the monograph on the RVG Legacy portal writes, his power was too small for the sound engineer. Let's remember that the signal on his tapes was very high, so he also wanted to be able to achieve similar results with the LP. He came up with what it would look like and went to Gotham Audio, which made a Grampian-Gotham Feedback Cutter System for him, working with a 150-watt Gotham Audio PFB-150 WA 150-watt amplifier.

How all this translated into the sound of Coltrane's album, what the people remastering it over the years got out of it, and finally which CDs and SACDs with this material are worth recommending—you will find out all this in the second part of the article.

Bibliography

Ashley Kahn The House That Trane Built: The Story of Impulse Records, W. W. Norton & Company, New York 2007.

Ashley Kahn A Love Supreme: The Story of John Coltrane's Signature Album, Penguin Books, London 2003

Lewis Porter, Chris Devito, David Wild, The John Coltrane Reference, Routledge, Abingdon 2013.

Havers Richard, Blue Note: Uncompromising Expression, Thames & Hudson, London 2014.

RVG Legacy. Preserving the Legacy of Rudy Van Gelder, RVGLEGACY.org, accessed: 2.02.2023.

Impulse 60! Collector's Zine, red. Barbie Bertisch & Paul Rafaelle, 2022.

Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, NJ - Virtual Tour, www.YOUTUBE.com, accessed: 2.02.2023.

Bert Caldwell, Simply Jazz with legend Rudy Van Gelder, YouTube 1994, www.YOUTUBE.com, accessed: 2.02.2023.

Jeff Forlenza, Rudy Van Gelder: Jazz's master engineer, "Mix" 254, 10.1993, p. 54-64.

D. Sicker, M. Sickler, K. Kimery, Rudy Van Gelder: NEA Jazz Master, Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Nov 5th 2011, AMHISTORY.si.edu, accessed: 2.02.2023.

SASHA ZAND, Rudy Van Gelder: Recording Coltrane, Miles, Monk, etc., “Tape Op", Jan/Feb 2023, TAPEOP.com, accessed: 2.02.2023.

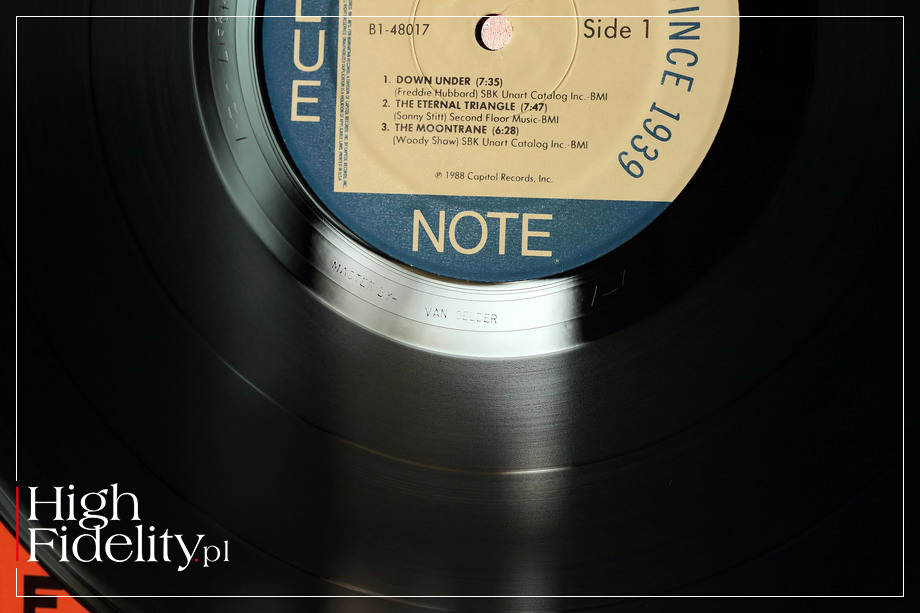

One of Van Gelder's hallmarks was his initials carved into the masters, like an artist's signature; in the photo there is a typewritten signature from the era of digital recordings

W. Clark, J. Cogan, Temples of Sound: Inside the Great Recording Studios, Chronicle Books, San Francisco 2003.

DaveDenyer: The Reel-to-Reel Rambler, THEREELTOREELRAMBLER.com HERE, accessed: 2.02.2023.

Peter Martland, Since Record Begin: EMI, The First 100 Years, Batsford, London 1997.

Howard Massey, The Great British Recording Studios

Howard Massey, Behind the Glass Volume 1: Top Record Producers Tell how They Craft the Hits,

John Pickfort, Vintage: EMT 140S Plate Reverb, MusicTech, May 28th 2014 , MUSICTECH.com HERE, accessed: 2.02.2023.

Blue Note Records

USA

text WOJCIECH PACUŁA

translation Marek Dyba

photo High Fidelity