Or, why recordings don't always sound the same.

We listen to music in various conditions, sometimes loud, sometimes quietly. However, in order to hear what is really there, we have to take into account, how it was mixed and mastered.

I don't know if you pay attention to the fact that a given album sounds sometimes better, sometimes worse—one day we listen to it with pleasure, and some other days we find it difficult to enjoy. It does happen to me, and I assume I'm not alone in it. There are several reasons for this. Among them the most important are: our mood, whether we are rested or tired, the quality of the power from the grid, as well as external noise.

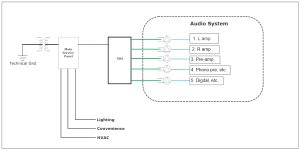

Listening to the Ayon Audio S-10 II during the Krakow Sonic Society 129th meeting

It is all important, real listening conditions. But it turns out that the most important thing is something else—the volume level we listen to a given album at. An album listened to louder usually sounds better than when listened to at much lower volume level, this is obvious and that is why it is so important to equalize the levels when comparing two different audio products, even down to 0.1 dB. Some recordings, however, do not allow the volume knob to be turned up a lot and sound better at low levels, while others sound better when played back loud.

What is it all about? Why is this happening? And finally—how LOUD should you listen to the music. Let me try to answer these questions. Let's start with the basics, i.e. what a dB is.

WHAT IS A DECIBEL

0 dB (zero decibels) is the standard atmospheric pressure. It is assumed that this is the threshold of what a person is able to hear (silence). It is also a reference point all other sounds are compared against. In music, a dB is used to measure the sound pressure, or the so-called Sound Pressure Level (SPL). This is how you usually determine how loud the music sounds - both at home and at a concert hall.

Contrary to popular belief, a dB is not a unit of measurement, but a ratio, a ratio of one value to another. This is an incremental LOGARTMIC, not LINEAR value. Thus, a +3dB gain in sound intensity corresponds to a two-fold gain, +10dB gain is a ten-fold gain, +20dB is a 100-fold gain, and +30dB is a 1000-fold gain. So if we want to increase the volume of the sound by only +3dB, we have to "ask" the amplifier to deliver TWICE as much power.

On the E-Home Recording Studio website you will find useful examples of the intensity/level of different sounds (ehomerecordingstudio.com; access: October 25, 2020). And so:

- Breathing sounds: 10dB

- Whispering: 20dB

- Normal conversation: 40dB

- Background noise at a restaurant: 60dB

- Listening to radio or watching tv: 70dB

- Garbage disposal: 80dB

- Jack hammer: 100dB

- Threshold of pain: 130dB

- Jet engine: 150dB

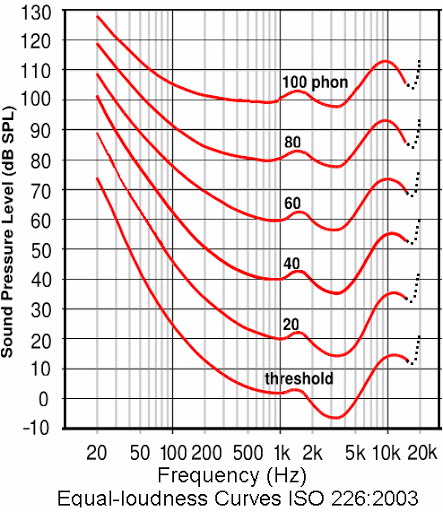

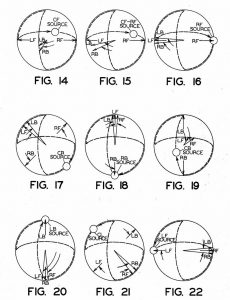

The given values are useful, but also subjective. Note that the listener's distance from the sound source is not stated. And yet every additional 1 m means a decrease in sound pressure by +3dB. Moreover, the subjective volume—let me remind you that it is not the same as the SPL—also depends on the frequency. This means that frequencies above 1kHz are perceived as louder by us, and those below as quieter. The relationship between loudness and SPL is described in the Fletcher-Munson Curve

Isophonic curves are defined by the international standard ISO 226: 2003 fig. Wikipedia.

In 1933, research on the subjective volume of sounds was carried out at Bell Laboratories under the supervision of engineers Harvey C. Fletcher and Wilden A. Munson. In the October issue of the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, they published a paper in which they presented how our perception of volume level changes with frequency. These studies were later specified several times, most notably in 1956 by Robinson and Dadson, but are still valid today. Nowadays, they are called EQUAL-LOUDNESS CONTOURS, and in Polish it is 'isophone' or 'isophonic curve.'

Oh, by the way Harvey Fletcher is the author of the oldest surviving stereo recordings, which he made in the 1931-1932; more at www.STOKOWSKI.org (accessed on: 25.10.2020).

HOW LOUD?

So we already know that how we perceive volume level is subjective. And that's why recordings sound differently depending on how loud we listen to them. So how loud should we play them?

One of the things Gerhard Hirt once told me about the workshop of highly regarded Dirk Sommer, the editor-in-chief of HIFISTATEMENT.NET, was that Dirk sets the volume really high during audition and testing. And that's quite normal—I do the same myself. But it is important to know that it is not always the same level. Each time when I reach for a disc, when I start to play a file I am looking for the level where everything "clicks" into place and when I can hear everything that is needed without getting tired and irritated.

And yet, at least in theory, each disc should sound optimally within a similar range of volume level. Why is it not so? The answer is very simple, on the one hand and complex on the other. Let's start with the former. The simple answer has to do with signal compression and the latter with the way the musical material was mixed and mastered.

Marcin Bocinski mastering (and mixing) Legato Mastering Studio. Photo press materials.

Excessive compression is the curse of the last dozen or so years. By itself it is useful and in most cases necessary, when used carelessly it massacres every recording. It is because of the so-called "Loudness War," or the pursuit of radio stations to play music as loud as possible, you can rarely listen to recordings from the so-called mainstream, because the labels insist that the album sounds as loud as possible, especially in a car. Such compression causes the dynamics of the song to disappear and the sound to become hard and irritating. Very often the digital signal is not noxiously distorted, which causes irritation and fatigue for a listener.

However, compression doesn't explain everything. The second, much more important reason for need of the volume being adjusted to each recording separately is the reference SPL principle (reference SPL). It is no coincidence that I started my editorial by recalling the relationship between loudness and SPL, as well as between SPL and timbre. It is so, that when mixing and mastering audio material, you should always do so with the same reference SPL level. Which is not always the case.

You can find information that mixing and mastering should be done at an SPL level of 85dB—it's very loud. The thing is, this is true for cinemas. This is reflected in the THX standard, for which cinema halls are measured at this sound level. This was due to the fact that the point of reference in the cinema are dialogues, and these were mastered at a level of 20dB lower than the maximum level, which was assumed to be 105dB.

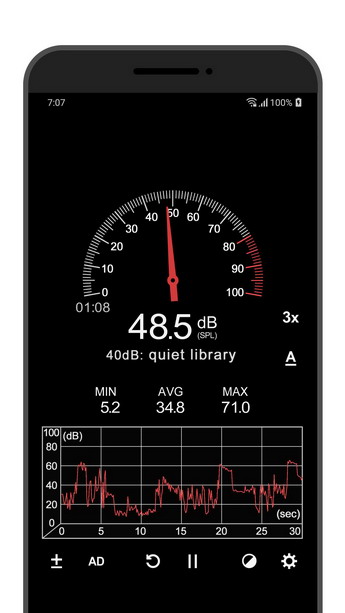

Sound Meter APK Pure app for Android devices apkpure.com. Photo press materials.

In recording studios that process sound, most specialist talk about 75dB. It's still loud, but it is bearable. If we listen to music louder we get more bass, if quieter—less of it. Unfortunately, this is a non-linear relationship, so it is difficult to "calibrate" it. So it would be ideal if a mastering engineer worked with the sound material at this level, and we listened critically to it at the same SPL. In home conditions, this level can be determined by playing a CD (or a file) with the so-called pink noise and measuring it with the meter. It could even be an app on your phone. It is important to apply a C "slow" filter.

But it's not that simple, unfortunately. Sound engineers listen to music with varying levels of intensity, but rarely the right one. Therefore, one should choose the listening level "by ear" during the listening session, using the value of 75 dB as a reference. In fact, it would be ideal if we would get information on the discs, what was the reference point for mixing and mastering. This would make our lives easier and allow us to evaluate devices and recordings with greater precision. And yes, all we have to do is believe that someone on the other side did a good job. And with faith, as it is with faith—there is never a certainty...

MORE ABOUT SPL

The Best Listening Level for Mixing, www.RICKALLENCREATIVE.com; accessed: 26.10.2020

The Musician’s Guide to Understanding Decibels, EHOMERECORDINGSTUDIO.com; accessed: 26.10.2020

The Perfect Monitoring Levels For Your Home Studio, www.MASTERINGTHEMIX.com; accessed: 26.10.2020

What Is The Reference Level? www.THX.com; accessed: 26.10.2020

What SPLs do you mix at? www.GEARSLUTZ.com; accessed: 26.10.2020

CRAIG ANDERTON, How to Mix at the "Right" Volume Level, www.SWEETWATER.com; accessed: 26.10.2020

DAVE MOULTON, About Playback And Mixing Levels: Levels Management II, Moulton Laboratories, April, 1996, www.MOULTONLABS.com; accessed: 26.10.2020

Hasło sound pressure level or SPL w: Audio Engineering Society, Pro Audio Reference, www.AES.org; accessed: 26.10.2020

HUGH ROBJOHNS, Establishing Project Studio Reference Monitoring Levels, Sound On Sound, maj 2014, www.SOUNDONSOUND.com; accessed: 26.10.2020

thegeeke, The Concept of Sound Pressure (SPL), www.INSTRUCTABLES.com; accessed: 26.10.2020

Text: WOJCIECH PACUŁA

Images: press materials own