This post excerpt comes in part from an email response to my friend Harold in the Netherlands. He was curious about our discussion related to my early MP3 work as an online musician through the '90s into 2000s, and how and why my MP3s could have sounded so good back then to literally everyone who heard them. At the same time in another email to audiophile Dez in LA how the audio gear available today has removed ‘computer' from the delivery of ‘computer audio.' Of course smartphones are all computers too, but what we usually mean by computer is a desktop, laptop, or even tablet. The network is becoming transparent. Music libraries can exist in many places, and a single playlist can reference any or all of them at will. The quality of the audio delivered to headphones and speakers can be streamed at studio master DXD quality using little more than 1mbps (1024kbps), which even my iffy satellite connection in Hawaii can support. This unfolds to 24/352.8k on my MQA Masters via TIDAL, and also on 7Digital, Deezer, Qobuz and other streaming lossless services.

If you can listen to studio masters from anywhere at anytime, there's no need for a sweet spot in a single room to go to when you want to hear your good sounding music. You don't have to lug it around on computers with you either. It is a new audiophile armchair-less world in these ways these days.

There are too many ways to hear music today. It creates lots of confusion and uncertainty about what any music listener should buy for equipment or should subscribe to for service. How much does good sounding music matter? How much does convenience in listening to the music that you like matter no matter where you are, including the BART or car or plane or hotel or work? How much does it cost to do either or both (have good sounding mobile music)? These are the questions of the day.

In the past 2 years I've observed huge gains towards a convergent path for these things that has never existed before. One can even look back at the introduction of CD in the consumer market at the beginning of the 80s, with the clear intent by Sony to disable and destroy the vinyl LP market it hoped to capture with new digital audio. It was cleaner and didn't hiss like tape or skip and pop like vinyl. Boo hoo. It also made the listener mobile with the first CD Walkman.

20 years later, the masses at all age levels particularly young generations have flocked back to vinyl as something that actually sounds good, so they produce it as artists and buy it as listeners. The production for vinyl can't keep up with the demand to print the good old 12" discs. Despite the fact that cassette was born along with early FM radio and lived with vinyl through the 70s and long beyond, it has stayed a huge favorite for younger generations making music through the Bandcamp explosion and many other outlets. Vinyl and Cassette win there. Analog wins! Sound Quality wins! CD is the dinosaur. Downloads and streaming are necessary conveniences and work when they need to.

Good sounding music always wins. That's what I say. Convenience comes in second after the thrill is gone, which can take a decade or more, no doubt. Still, sound quality wins.

When I started working with DSD as an independent artist and was invited and treated kindly beyond words by some of the Sony SACD Project team to participate with their newly evolving DSD gear, I was able to record and hear what my natural acoustic singer-songwriter material really sounded like on excellent digital recording and reproduction setups. I'd been doing things with my songs as recordings from the early 4-track Tascam cassette players in the 80s to the then-current mid-90s 16/44.1 and 16/48k PCM multi-track (usually up to 8) recorders. I had cut my teeth on this approach with four self-produced and self-released home studio CDs in the market on CDBaby (I was one of first 50 artists signed up there), and online via my websites since 1995, where I was handwriting HTML to code the pages using Windows Notepad because Dreamweaver and the rest of the WYSIWYG tools hadn't been invented yet.

DSD instantly solved everything I didn't like about recording digital; I was even not thrilled with results from some 24-bit leading edge workstations I was able to test things on, like the early Waveframe. It was always a compressed-sounding result, and lacked natural sustain on notes and breath released, and didn't have any warm cozy acoustic ambient cushion to place the real song and real performance onto for listening to the playback, no matter how much work was done trying to fix that in the mixes using EQ or effects like compression, reverb, delay, and the rest.

So DSD was the instant magic sauce for me. I heard it first used on early Sony legacy jazz and folk/rock archive tapes transferred from analog masters to DSD64. It was played from a prototype Sony archive workstation into my home studio setup, which of course I knew the sound characteristics of. And what I heard through my speakers then changed the way I listen to music to this day. It's been elaborated on and compounded more than I ever imagined, and I'm still working on the art of listening, which in a large part involves unlearning a lot of old habits for listening based on compressed sliced-and-diced CD and other digital recordings since the 80s. It's hard to unlearn how to listen, but one has to to let really good recordings seep into our ears and brain's recognition of sounds correctly to enjoy fully. Spatial and temporal issues are at the heart of much of the problems with standard PCM recordings, rendering them unnatural sounding and hard to listen to for hours and hours and hours without getting fatigued, and maybe suddenly hating having any sound in your ears at all. DSD, MQA, and now iFi Audio's GTO filter (along with other earlier minimum phase and apodized filters) all address these big problems in different ways.

When I was able to take some of the early DSD recordings I had (2002 – 2006) and convert them to a format that I could deliver to some of the online musician forums I was participating in to share my work in its best sounding quality, it was of course not in the native DSD format they were recorded in. This was in 2000. The world had barely advanced to the wonders of 33.6k and 56k dialup modems to get to the internet. ISDN tests on the public network by the phone companies had already all but come and gone. What was left was early ADSL (DSL) at max. around 1.2mbps in the US for download, and far less upstream speeds, and the early cable modems at maybe around 5mbps. But the cable modems were then—as they are now—shared, so you couldn't rely on any fixed throughput for downloading anything when your neighbors or coworkers were online nearby.

There wasn't much audio streaming then. It was all about new ideas of how to download music for a price per song or album (iTunes) onto your PC or Mac to play later at will. You built a CD library by ripping yours and your friends' CDs, and downloading MP3s or AACs at 128k or less from Apple and a few others, or wherever you could find a Napster or the like. Crappy sounding music for the most part, yes, at rates up to 128. Pandora was, and still, I believe, streams at 64kbps. Very crappy sounding, which is not a knock against MP3, just the low bit rates used by almost everyone even today except Bandcamp, Spotify, and a few others not serving lossless streaming. How so many others using the same old low MP3/AAC streaming bit rates get away with it, I have no idea. Maybe their customers have never listened to anything better, and expect it to be the way it has always been. MP3 sampled at 256kbps and 320kbps on the other hand is often hard to distinguish from CD quality, and in fact may have fewer errors in the sound file and could even sound better than the source. Another subject for another day. I'm not a a big fan of either high sample rate MP3 or Red Book CD, but what I mean to say here is that a lot of much worse quality has been clogging the ether pipes for a good 25 years now and still is. Shame on some.

So with my 4 released CDs (Lost in the Green, Time Forgets, Half An Hour Away, and The Blue Planet) and lots and lots of unreleased songs as digital masters, I wanted my stuff to sound as good as it could online in the forums. A good example of the forums (before Myspace—don't get me started) was a place called Mixsposure. I think a version of Mixsposure may still exist, and for all I know some of my songs might still be up there. I really don't know.

But it was a great collection of musicians from all countries sharing their original work and getting listened to and reviewed and rated to some extent through the forum. Those were days of truly constructive (not destructive) criticism, with common interests in self-producing good-sounding albums with good songs. Lots of music to hear and some really nice friendships made long distance in those early music online days. I enjoyed it and participated quite a bit. It wasn't the only site I went on over those years, there were tons coming and going and I tried to try all of them to see what I preferred. But Mixposure kept its cool while others crashed and burned or got nasty as in Myspace.

So my DSD conversions to MP3-128 and MP3-256 were uploaded slowly slowly slowly over DSL to Mixposure et. al. and posted for everyone to take listens to. The results were always surprisingly and even embarrassingly strong and forward. Musicians online in 2002, 2003 heard things I'd created for my The Window SACD release using DSD and simply converted to MP3 using PCM converted test mixes of my DSD 2-track and multi-track to stereo projects, along with PC tools like Audiograbber and others to create the MP3s with the LAME encoder. Then early versions of Audiogate from Korg appeared in 2006 which I used as a main tool for lots of DSD mastering and exporting to other formats including MP3. Audiogate was also the way I worked with Gus Skinas at superaudiocenter.com to create the first Sony DSD Disc download (as a zipped ISO image for DVD burning) in 2009. The Window DSD stereo master was then getting downloaded into a Sony Playstation3 for native playback, as well as on some special Sony and Onkyo players with USB inputs.

These ~2GB album files were no easy match to download for many people, as the cable modem world hadn't expanded greatly beyond some of the same early 5-10mbps limits. But hell, we had to wait an hour for a CD to download 10 years before at 33.6k dialup, so fair is fair, right? Netflix had the same problem with their early streaming in 2009 as well, when they begged their customers to make sure they had at least 5mbps download speeds at home so the movies would not hiccup and stall and stutter in the middle. (Does any one else get the little chime going off in their head for audio that points to MQA's design to stream at often under 1mbps and still deliver a 24/384k studio bit perfect master unfolded and decoded at the listener's end — I do. They are a killer vending machine of their own with their design.)

WHY DID MY ARTIST TRACKS ON MIXPOSURE SOUND SO GOOD AS MP3

There is a word that the industry has come to use called "provenance." I don't know where its use in audio came from, and don't particularly like the word's implications and confusing context definitions in Websters, but for audio it simply refers to the quality and care used in making the source studio or live recording. It's what goes into making a good master. Provenance is completely agnostic to all the media types and equipment types used. It (the recording) just has to be done well.

Provenance has always been at the top of my list, regardless of the term used to refer to sound quality or the media used. (I made one CD "Voice Memo: Songs From Hawai'i" in the past few years, with 30 tunes all recorded on my iPhone using the smartphone's stock Voice Memo app. Then I mastered it all on PC and released it on CD and download. I used provenance including the phone's mono mic proximity for voice and guitar, levels, upsample, and mastering on PC using Audacity, to the maximum capabilities of the environment I chose to make that album in. The album idea was to capture the process of songwriting, as since 2007 I often record new songs I'm writing onto my iPhone to capture the true original song, and remember how I wrote and played and sang it as I was writing it.)

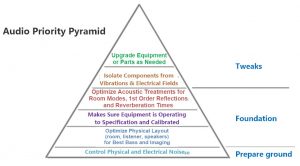

Anyone can make a terrible recording using DSD, just as they can do so using an iPhone. As I've written before online, the things that make all the difference to what the listeners end up valuing are in my mind staged in a very particular order of precedence:

First is the performance of the musicians

This trumps all else in my opinion. Along these lines but much more subjective is the quality of the song itself. Good songs sound better, kind of a no-brainer, but what constitutes a good song is of course up to everyone to decide for themselves. Still there are many commonalities the public has had about what good songs are, otherwise there would be no Billboard, or Grammys, or CMAs, but don't get me started there. Suffice to say that finding good songs is not always as easy as looking up Billboard, or lookup up the Grammy or CMA winners, or reading a magazine's best-of. It never was that easy and never will be in today's exploded-quantity-of-music world.

Next important is the quality of the engineering used in whatever setting the music is recorded in (studio, field recording, concert, kitchen table…)

Proper selection and use of microphones and any preamp or other gear in line to the recording device is an incredibly important factor on delivering a good result. Setting up these devices properly, which includes things like proximity (where to place the microphone and how to angle it), are all tasks for qualified sound and recording engineers. Anyone can do it but not everyone can do it well.

Third important is the gear to record the music

This includes analog tape machines including reel-to-reel (R2R), cassette, and digital machines like MP3 or CD/HD portable, studio quality PCM/DXD or DSD workstations. This has to be done correctly without clipping and all the other problems that can arise.

Fourth is the art of mixing and mastering

This is critical as it can both destroy a perfectly perfect recording by doing things (to my ears) like adding compression, unneeded effects, overdubs, and edits, and otherwise chopping apart the sonic values of the performance and turning it into something else much more manufactured sounding. On top of that, the nature of mixing is to literally create the environment (2D, 3D) that the listener will experience a multi-track recorded album in their setup. Good mixes are just that and vice versa. All art, no bull. Nearly all my recordings took just part of one day or just a few days to record, and then many months to mix and then master. I'm not saying my albums are automatically good because of that, I'm saying that mixing and mastering are no bull.

Fifth is the media delivery

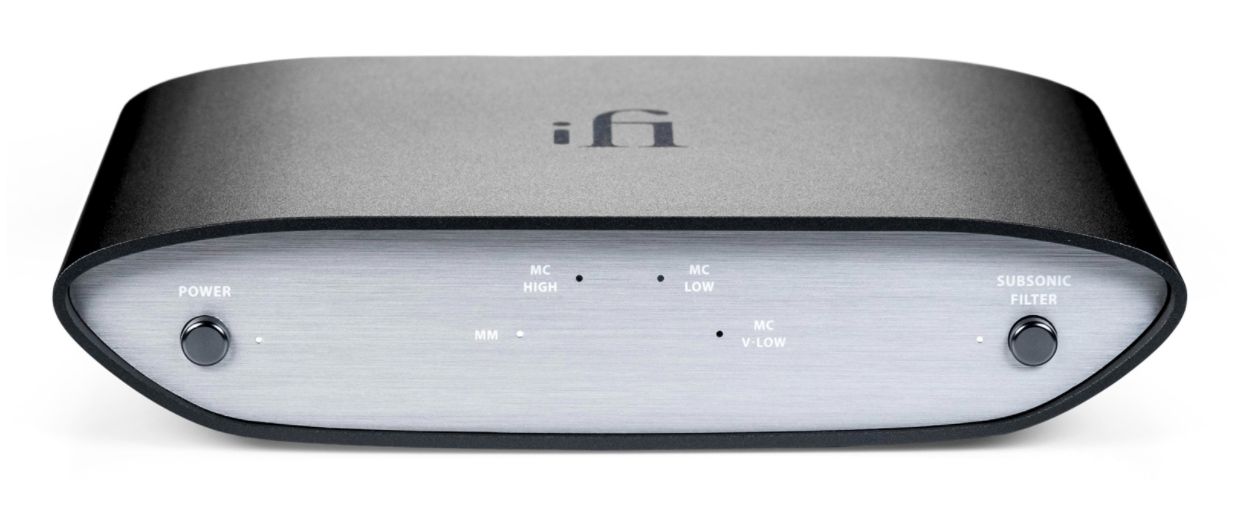

This can include streaming or downloads as lossy or lossless, with extra improvements in the proper circumstances such as MQA decoding at the listener's end, or gear like the iFi Pro iDSD to do such reconstruction on its own during playback in the forms of GTO filters and then DSD1024 upsampling to further allow the music to sound more analog-like in very very real and distinctive ways to the listener.

Those are the 5 steps in order that I think need to be addressed to result in a media portable recording that can literally be played or sprayed through the ether anywhere to any device and still sound very very good within the context of how it is being played.

Doing these things above correctly to the fullest extent allows low converted (downsampled) streaming or downloaded 128k MP3s, CDs, or anything else to sound better than any other low-quality 128 MP3 tracks, CDs, or anything else, as far as sound quality at least. It only gets better from there with the higher res formats for delivery. And if the listener is setup for hi-res reproduction in the native format of the source recording (say DSD64, 128, 256 or MQA 192, 352, 384), then guess what? They will be blown away every time.

So if a golden master is created with high degrees of provenance, then its good sound to all listeners travels from its source master (DSD64, DSD128, DSD256, DSD512, or DXD (352.8 or 384), MQA (DXD with MQA encoding, or MQA CD 16.44.1kHz PCM with MQA encoding) to any other downsampled format such as MP3 for say downloads, or streaming on Bandcamp or Soundcloud, or Garageband or LastFM, or Streaming on Spotify (which can use 320k and sounds very good) or any other use—even Pandora at 64kbps.

In my world MQA PCM always qualifies as significantly improved provenance to the source PCM without MQA so this applies equally to MQA CD and and 24-bit encoded PCM remaster at different bit rates 48kHz, 88.2kHz, 176.4kHz, and 192kHz.

Bandwidth, cost, OTG lilfestyle issues, are just some of the reasons music has to be available in many formats today. The transparency of the network itself is essential and critical. That includes gear, music players as apps on phones, tablets and computers, wires or wireless protocols (Bluetooth vs WiFi, Airplay vs Google Cast), and finally the output devices (wireless/wired speakers or headphones/earbuds) are essential and critical. The details of HOW and WHERE one listens to ONE'S MUSIC has to become less and less and less important, and eventually invisible, with the requirement to still have very very good-sounding music coming through to our ears.

So once again, my point for all of this post is in the paragraph above. With that becoming an advanced reality more and more each day, the armchair requirement of the dated audiophile of the 80s and 90s is becoming a non sequitur, and so the armchair audiophile in a single room with a limited library of music has all but faded into the past.

Amen to that, since it also means that the burden of finding a single sweet spot in a room to listen to great sounding music is not quite the burden it has been in the past for all of us, nor does it cost as much to find just about anywhere. This is just as true for diehard audiophiles as for anyone else.

Live Long!

~ DE, January 11, 2020

Cover Photo © 2020 David Elias, "Standing Waves

For more from David Elias, please go to https://davidelias.com.

To purchase his albums in DSD, go to NativeDSD.com at https://www.nativedsd.com/albums/SSP1661D64-crossing.

David's MQA recordings can be found at https://davidelias.bandcamp.com.