Audio Equipment is the Servant of the Music

"The driving force in what I've always done up until now, and that won't stop, is that I really see the equipment as being the servant of the music. Equipment should really be invisible to the music, but it never will be, the best you can do is reduce its influence on any given recording as much as possible."

"What you cannot do is remove it completely from the equation, because then you are back to live music, and who the hell can get an orchestra in their front room. Not many people can do that."

"So, what we get is miniature versions of very large events, and when they are well recorded they will give you a believable and musically authentic representation of what was there. In many cases they don't, but that doesn't mean you don't like the performance, you may not like the sound, but then again, the sound is really the packaging of the performance."

Public domain photo of the Dohnanyi Orchestra Budafok courtesy of Wikipedia.

"Just like the idea the soundstaging, imaging, and so on, is somehow an important ingredient, and it is one of these things that is very difficult to get customers to understand—particularly with modern recordings—there really isn't any of this on the recording, because the recording was done with each member of the band, or with an orchestra it is done with thirty-seven microphones, with one microphone over each section of the orchestra. Then it is all put together, so you have these fragmented bits that are all put together in the mixing and mastering process."

"The idea that this somehow is an important part of the performance, is that in my modest opinion is just nonsense. It is completely utter nonsense, and what it does, and particularly what it has done in the high-end industry, is that it disqualifies the entire musical heritage from pre-1955 before stereo."

"Certainly, in classical music, and to a large extent with jazz, the vast majority of the really valuable part of our musical heritage sits in the mono catalog, and in the 78 catalog. It seems absurd for an industry to favor ways of listening, and ways of evaluating quality, that nullifies some of the most important and interesting documents in the musical catalogue."

"… discussions that took place from when we went to the original Edison roll to the flat disc 78, or what happened between from when we went from the acoustic recordings to the electric recordings in the mid-1920s."

"Those discussions are very important to understanding what our view of music is and how it should be reproduced, and what is important in how music is viewed as a cultural artifact, if you can call it that."

"I think there is a problem with the vocabulary which we use to describe audio, it really misses the point. 'Accuracy'—what the hell does that mean? 'Neutrality'—what does that mean? I prefer words like 'authenticity.'"

Comparison by Reference Versus Comparison by Contrast

"I've developed the philosophical foundation of how I've evaluated—with a piece of equipment, or a resistor, or a capacitor, or an entire system—how well it does its job."

"Basically, the idea there is quite simple, that we do not know what is on the recording, because at the end of the day we don't know what was picked up by the microphones. We know what the piece of music is, we know who the artists are, but we cannot with any certainty say that the microphones or the rest of the equipment in the recording process did the job we expected them to do. Therefore, from that it follows that the only thing we do know about recordings is that they must have a different sonic signature, that has little to do with the music, it has to do with the way the recording sounds."

"So instead of using an evaluation system which by and large you can call comparison by reference - comparison by reference is where you sit down with a number of known recordings, and you then play those on an amplifier, pair of speakers, etc.—but the mere fact that you use these records as a reference means that you assume that you know what is on those records, but you can't possibly know that. There are a lot of things you can know, the music, the artists, and so on, you can know one recording is better than a lot of other recordings in the presentation, but what you cannot know is precisely how the recording sounds."

"This is where comparison by contrast comes in. If you take, which is how we tend to develop these products we make, all the parts that we make and design, by listening to 5 or 10 random records, then we listen to them to see if a given piece of equipment, circuit, or component, is whether that makes the recording sound more different, more individual, from the other equipment, circuits, etc., that we are developing."

A Music Lovers Versus Audiophile Style of Presentation

"That's easy to do, but you have to unload so much of this audiophile nonsense that is so dominant, most of which comes out of the US. You have to get rid of this idea that "Oh I know what the violin sounds like on this record," or "I know what the piano sounds like on this record." Or "I listen more in the sound field where the instruments are," in spite of the fact that you don't really know where they are. The mere fact that you use more microphones actually creates a problem in the timing of how the instruments sound together."

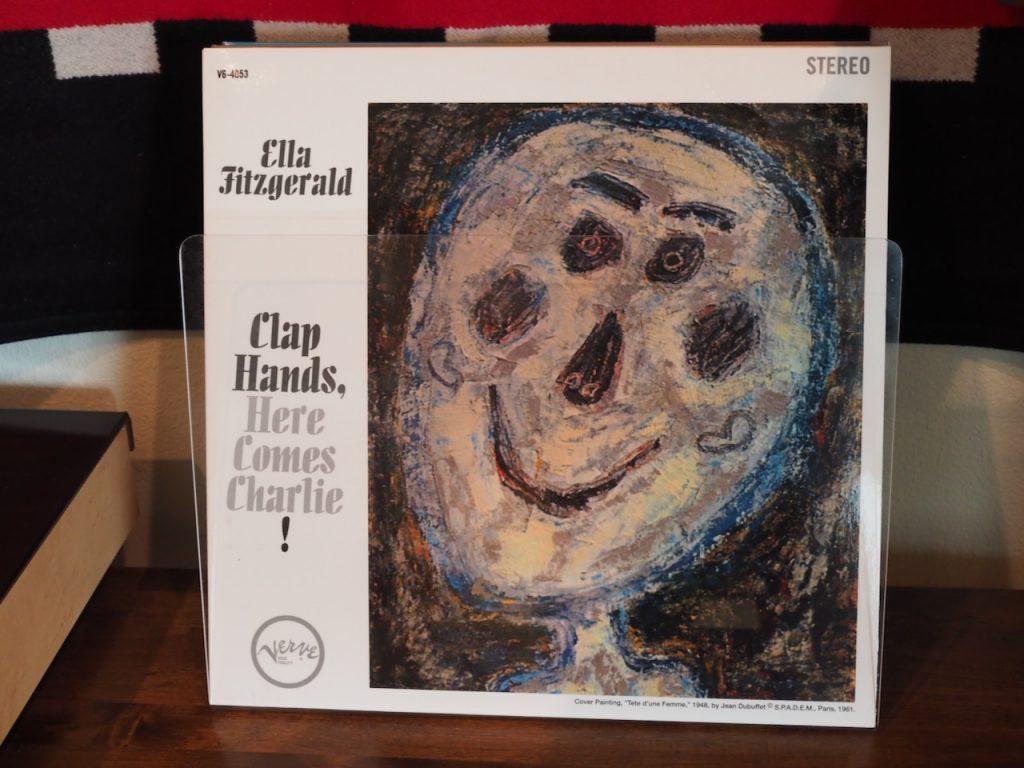

"There's a very famous test—I think Dick Olsher did this originally, but I'm not quite sure—where they took the latest re-release of Ella Fitzgerald's Clap Hands Here Comes Charlie, and they compared the Analogue Productions with the original stereo version, and then they compared it to the original mono. I have all three, so I can do exactly the same comparison."

"It is very interesting when you listen to the timing, it is quite a small band, and with the mono all of the sounds from the different instruments arrive around the same time. When you have several microphones on the stereo version you get a very subtle change in the timing in the way the instruments play together, and you can hear that. You have to listen closely, but you can hear that."

"That begs the question of "Why did we get stereo in the first place?" Because they knew this. I had early discussions from the technical department of EMI, where there were lots of discussions about this, and this was one of the points that the recording engineers made at the time. So, what they were saying was we need to stick with mono, but use two speakers, two amplifiers, but then play mono."

"I've done tests at shows over many, many, years, where I would play the mono version. I would have the stereo jacket for the record, but I had the mono version in it, and I would play the mono version. I would put the stereo jacket up so people could see what's playing. I have never had a single complaint that it didn't sound like stereo."

"If you study the comparison by contrast method in more detail, one of the things you'll realize if you hear a system that is good at presenting the contrasts, it becomes pretty obvious what you should be listening for."

"I've tested this on many people over the years, and what is very interesting is that most of the people that respond well to this, do not carry too much audiophile baggage. They are listening for parameters that they know."

"They have this expectation of imaging or soundstaging or whatever it is … I have a record, Bob Sharples' Dimensions in Sound, and is one of the more interesting records to own. What is interesting about this record is that it is clearly described in the text on the back, where in the sound-field the instruments are, how far back they are. This allows you a more effective way—all things being equal—of judging what your system is actually doing."

"It's quite easy to make, for example, a loudspeaker that presents imaging in a certain way on a multi-mic'd recording. All you have to do is have a slight raise in the energy band from somewhere between 2kHz and 5kHz, which is where a lot of this information sits, and the result is you get better imaging and soundstaging."

"But at the end of the day all of this is packaging of the sound, it is not the sound itself. That's where I think the industry has completely and utterly lost its way. It is incapable of prioritizing what it is that matters."

"When you speak to musicians—I have a number of quite well-known musicians on my client list—several of whom have become friends over the years. When you sit and talk to them they start out saying, yes, all of this matters."

"But then you play them systems, and you start playing them old recordings from 78s, particularly recordings from the acoustic era. Now what's special about those recordings is that the distance between the man singing into the horn, and the membrane with the pin that copies the sound into the lacquer, is very, very, short. So, the distance between the actual event and putting it down to document is very, very, short. Yes, there are issues with distortion and all kinds of other things, but there is an authenticity to recordings that are done this way."

"When you listen to people like Caruso, Martinelli, or any of the other great singers from that period, they were all recorded this way. They were not recorded using any kind of electronics. It was purely mechanical and acoustic."

"There is something about those recordings, they capture something that nothing we've done since captures. That begs the question, "What is that we are missing?"

"Why are we not, with all of our fancy technology, why are we not capturing this? Why are we not able to capture that? It is in the sort of phrasing, and the sort of emotional content, if you will, from these recordings. We don't pick that up with modern equipment."

"I've spent a lot of time in the studio, because I act as an acoustic advisor to a very famous conductor, a friend of mine. So, I've spent many hours at the recording venues listening to the downplay, back-play from the recordings, listening to the individual microphones, and all sorts of things like that, and the conclusion I've come to is we're really not doing a very good job of it. This is in spite of the fact that his readings of the particular pieces of music we are recording are quite phenomenal by any standard, historical or otherwise. It is just that the document we are creating does not reflect that."

"The question of subjectivity is what kind of music you prefer, not what the sound should be. If there's music I really like, but the recording is bad, I still listen to it. I listen to music that goes back to the 1890s. I can tell you one thing, it is not a great sound, but the performance is really worth listening to. Being able to listen to Edvard Greig play his own Papillon in 1903 shortly before he died, that is a form of time travel, the only form of time travel that any of us will ever do. Same as with Chaliapin singing The River Maiden, or whatever, that is what is so special about these old recordings, that we can delve back into and listen to people that have gone on many, many, years ago. These things have a value that goes far beyond this audiophile bullshit, to be perfectly frank with you."

"I see my job as to make my audience understand the value of this by producing equipment that allows them to access it in such a way as they get the core musical message rather than just the noise from the 78. Audiophile equipment will just give you the noise, which is why many people don't listen to recordings like this."

"If you listen to really early stereo recording, like Sonny Rollins Way Out West, on the original stereo version of that you have the saxophone on the left, and the drums and bass on the right – that is "stereo."

"The Electric Recording Company released what probably the finest re-releases of Way Out West, and they purposely released both the original tapes on stereo, and they re-released them in mono. These were done by different microphones simultaneously. The stereo is somewhat irritating to listen to because of the way it is recorded, and the mono is much preferable."

"I think again that history is important here. It is important to understand history. I study economic history as well. We are good at forgetting things that don't fit our particular set of biases, for example. That's very common, and I would say it is more common than not, but that doesn't mean we can't learn from history, and in fact we would probably be better off studying a bit more history and a bit less technology. To understand why things ended up the way they did. Once they started being able to record with multiple microphones, as we went through the 1960s, you can hear a very gradual degradation of the quality of the source material."

"This is one of my main interests in life, and I also happen to make it my living, so it mixes itself very nicely there."