Herb Reichert (left) and Lynn Olson at RMAF 2015: a moment (photograph and image processing by David W. Robinson)

Although some of you may know me as the sometime Tech Editor of PF (and that only occasionally, when the mood strikes me), and the designer of the Ariel loudspeaker and Amity and Karna 300B triode amplifiers, I did have a prior life in audio, back in the early 1970s. Those were my days at Audionics (later renamed "Audionics of Oregon" due to a trademark conflict with an obscure company back East).

After I flunked out of Pitzer College, in Claremont, California, the only job I could find was as a salesman at a local stereo store in nearby Pomona. This was a high-pressure commission sales job: there was a chart in the back of the store, next to the warehouse, where all of the salesmen (and it was all men back then) were ranked by profit margin combined with gross sales that month. The salesman at the bottom of the list was fired at the end of the month. (This is still the system used in a lot of car dealerships, so buyer beware.)

The pressure of just surviving was getting to me… every day, sell, sell, sell and shade the truth as much I could stomach and still keep the job. Surprisingly, many of the customers made that easy … all they wanted was a big discount, and we had just the system for them: an ultra-high-margin setup with 100% house-brand "components" with an astounding 80% profit margin, so we could discount as much as the customer demanded and the store still made a profit. My idealism educating the public about the wonders of "good sound" evaporated in the first four weeks of that job. Remarkably, I was able to stay there for eight months, but I was slowly losing my mind (and certainly any moral sense) with every day on job. I had to get out… NOW. (Anyone's that's ever worked in commissioned sales will know the feeling.)

I was also a big fan of quadraphonic sound at the time, but was far from satisfied with my own setup. The JVC CD-4 discrete FM-carrier system barely worked, every speck of dust made a huge BANG in the demodulator/decoder, and the Sansui QS Vario-Matrix sounded good, but very few records used the format. The CBS SQ system was on many favorite records, but the decoder didn't sound as smooth as the Vario-Matrix, and it also sounded kind of closed-in, which kind of defeats the purpose of quadraphonic sound.

Long story short (you'll see more in the linked thread below), I invented a higher-order, 3D version of the Vario-Matrix, spent a couple of weeks researching it at the Los Angeles patent library (no online access back then), and filed a Document of Disclosure (which is a kind of do-it-yourself mini patent) and mailed it off to Audionics (in Portland, Oregon) and Advent (in Boston, Massachusetts). There was no reply from Advent (who were busy with the Advent Videobeam projector), but Audionics was interested enough to have me move up to Oregon.

A month later, my sweetie, our St. Bernard, and I drove up I-5 to Portland, Oregon. What a drive… a 1961 Ford Falcon with dim sealed-beam headlights on a dark, rainy two-lane road with terrifying log trucks going the other way. We arrived in Portland in one piece, dog and all, found a place to rent close to Lloyd Center, and I started at Audionics, consulting with their chief engineer, Cliff Moulton, while I worked a day job assembling circuit boards on their amplifiers, measuring and checking the completed amplifier, and boxing them up and shipping them out.

I spent the next year or two working evenings with Cliff on what became the one single Shadow Vector prototype, which took about two years going from the initial concept in the Document of Disclosure to a working prototype. The prototype was a plain black box with a single volume knob on the front, L and R inputs on the back, and Left Front, Left Back, Right Front, and Right Back outputs on the back. Inside the black box, there were 10 circuit boards: 1 input buffer and Axial Tilt Corrector circuit, 2 all-pass phase shifter boards with 0 and -90 degree outputs, 3 direction-sensing boards, and 4 variable-matrix boards (each with 3 gain-controlled amplifiers). There was also a hand-wired backplane that connected all of this together, and a test and setup protocol for optimizing separation for any phono cartridge. We listened to it for several months on a wide selection of CBS and EMI SQ-encoded records. The setup I used at home were 4 KEF 104 loudspeakers and a stack of Radford preamps and amplifiers. (Audionics had been the official US importer for Radford for several years before.)

The initial demo back East (upstate New York, as I recall) was an unexpected disaster. Cliff Moulton used time-switching FETs as the variable-gain amplifiers (3 in each channel, 12 in all), and they were surprisingly prone to RFI interference from nearby radio stations. With no signal going through the Shadow Vector, you could hear 2 or 3 AM radio stations in the background, and with a record playing and stimulating the decoder, the AM-radio interference moved all over the room in a crazy way. Crude attempts to wrap the prototype box in foil didn't work, so the demo had to be called off. Our host gracefully deflected the assembled audio press with a catered dinner at his home, and I guess at some point, before or after the demo, I did a radio interview for New York Public Radio (link below). Although I have no memory of doing this interview, and don't even know where it was conducted, I'm guessing from the confident tone it must have been before the disastrous introduction of the Shadow Vector.

Later that year, we successfully introduced the Shadow Vector at the 1975 Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago, where guests were entertained with a Tektronix dual-beam scope showing the localizations sensed by the decoder. CBS Labs came by, since we were an SQ licensee, and that was the first I heard that CBS had their own variable-matrix decoder (like mine), but it was confined to the lab, and not known to the rest of the audio press. I was more surprised to hear the 3-man CBS team of SQ designers had to hire an outside mathematician to design the CBS Paramatrix decoder (as it was called). With the aid of Scheiber notation (which you will see in the linked articles), I was able to create the whole Shadow Vector … without the Scheiber spherical notation, yes, an SQ variable-matrix decoder would be insanely complex and nearly impossible to visualize. Anyway, I heard their prototype at a private demo at the same CES, and it sounded noticeably different than Shadow Vector, so I guessed the operating principles were not the same (which was a relief after all that work).

In 1975, three of us from Audionics (Charles Wood, CEO, Gene Still, marketing, and myself, the inventor) went to Europe and demonstrated the Shadow Vector to BBC Labs, EMI Records, and also visited KEF Loudspeakers, where I met Laurie Fincham and saw how computer-aided design could be used to design loudspeakers. (This was in the days of $150,000 DEC minicomputers that filled an equipment rack and required an in-house FORTRAN programmer to write the FFT code for the test system.) The 2nd radio interview was done a few weeks after our return from Europe, and most likely only a few days before the cancellation of the Shadow Vector project.

The 1974 interview on New York Public Radio (preceding the public debut): HERE

The 1975 interview on New York Public Radio (following the trip to Europe): HERE

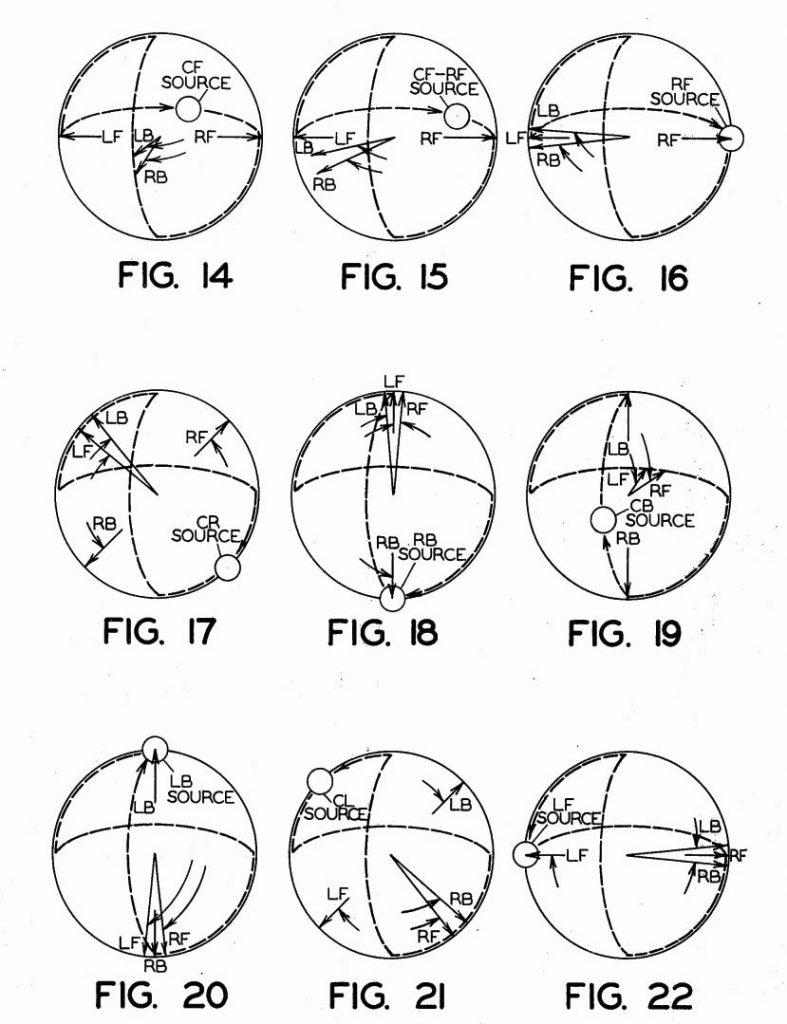

Let's jump into the deep end of the pool: here's some of the artwork used in US Patent #4018992. This is Scheiber spherical notation, which represents the L and R ratio on the left and right sides of the sphere, the front (pointing away from you) represents L+R at 0 degrees, the top represents a 90-degree phase shift between the two channels, the back represents a 180-degree phase shift, and the bottom a 270-degree phase shift. The SQ, QS, EV4, and Dolby Pro-Logic encodings can all be mapped on a Scheiber sphere, which shows all possible relations between 2 channels.

That said, the figures show what's called a "pan-locus" as a signal is panned in a circle around the listening space. It is a 360-degree SQ-encoded pan from Center Front -> Right Front -> Center Right (right wall) -> Right Back -> Center Back -> Left Back -> Center Left (left wall) -> Left Front. The ball whizzing around the Scheiber sphere is the SQ-encoded source, and the little vector arrows show the dynamic matrix for each channel scooting away and hiding 180 degrees away from the encoded source.

This is why I named the decoder Shadow Vector; the four channels try to stay as far away as possible from the encoded sources (staying in its shadow), and move in 3 dimensions to do so. There's no "cancellation" per se, unlike the CBS full-logic or TATE DES system, or any others. All that happens is the matrix is like a cat's cradle, continually shifting to keep the image sharp and well-localized, and giving the most resolution to the loudest direction of that moment. It moves very fast, 10 to 30 times a second, but the random-phase reverberant energy is unaffected, since the matrix always retains constant energy from input to output. All that happens is that spatial resolution is momentarily reduced in the directions that are quietest, and the loudest directions are given the most resolution. If the direction-sensing "logic" can't determine any dominant sounds (as in multi-miked classical recordings), the decoder simply reverts to a passive matrix.

Very shortly after the 1975 radio interview, the Shadow Vector project was terminated in favor of the TATE DES project by a rival team in Hollywood, Wesley Ruggles and Martin Willcocks. I knew at the time that the rival team existed, but I wasn't aware that I was in competition with them, and they had Hollywood backers who had the deep pockets to pay for National Semiconductor to reduce the entire TATE system to a pair of custom-designed integrated circuits. As it turned out, National Semiconductor only did part of the job, so the Audionics Space & Time Composer (yes, that was really its name) required a fair amount of add-on circuitry to make the thing work. I was long gone by then; I only heard about this part second-hand.

As for me, I was given a choice when Shadow Vector was terminated: either finish a 6-foot-high transmission-line loudspeaker with 4 drivers (the original designer fled without a forwarding address or phone number), or get laid off. I had never designed a loudspeaker before, but Charlie figured that 2-hour talk with Laurie Fincham was enough for anyone. Six months later, the TLM-200 was completed, and I think we sold a grand total of 12 pairs. The later speakers I designed for Audionics were more successful, and built on the Radford transmission lines Audionics had imported a few years before. Later, I worked with Bob Sickler, designer of Audionics' best amplifier (the CC-2) and a runaway success, and then I left for Tektronix in 1979, narrowly missing the mass firing of Bob Sickler (engineer), Gene Still (marketing), and the accounting whiz in the front office who kept Audionics afloat.

I always thought of myself as the "unindicted co-conspirator," since I would have been caught in the mass firing if I'd still been there. But I wasn't. I got out while the getting was good, but my first job at Tektronix was going from the frying pan into the fire; the group we were in at Walker Road was not profitable and due for closure, but I quickly found a job at the main campus in Beaverton, writing dense manuals for the Spectrum Analyzer Business Unit. While I was cranking out various manuals at Tek, I watched from a distance as Compact Disc wiped out the LP (records were off the shelves in Portland stores in less than 12 months), and the high-end industry got lost in hyper-expensive, poorly designed products in the Eighties.

A few years later, my ranting and railing against the Big Two magazines in the early issues of Positive Feedback was the result of my dismay at seeing the Big Two magazines become the de facto gatekeepers on the entire industry, and the frankly terrible taste of the big-name reviewers. I resigned my membership in the Audio Engineering Society as the magazine changed its focus from improving audio to more and more shitty lossy-compression codecs… the default assumption that 44.1/16 digital was magically "perfect sound forever," so why not focus on squeezing the data rate down from that point? I didn't get back into audio again until I joined the Oregon Triode Society in the late Eighties, and that's where I met David Robinson, the editor of the little newsletter of the OTS … which became what you're reading now. I knocked out an article or two and things just went on from there.

Flash forward: out of the blue, a couple of weeks ago, I got an email from Malcolm Lear, a man in the UK who had read the Shadow Vector patents and was doing the whole thing in software! Amazing! Astonishing! My original design work was 45 years ago!

He described his sonic impressions, and yes, that's what exactly Shadow Vector sounded like. Much more spacious and resolved than Dolby Pro-Logic II or DTS Neo:6, which I have on my Marantz AV8003 preamp. Thanks to the power of modern DSP, Malcolm's software version has a digital look-ahead feature that can anticipate rapid changes in direction, and also has band-splitting, in the same way as Dolby A noise reduction. That startling news motivated me to jump into the Quadraphonic Quad SQ sub-forum, and I publicly thanked Malcolm in the UK for having the perseverance to go through with his project. I'm eagerly anticipating hearing Shadow Vector after all these years. Here's the links to where I jump into the forum (if you want to see the artwork, you can join the forum at no charge).

There's more than one post, of course, and one of my subsequent posts in the "Quadraphonic Quad" forum is a lament about the immense gulf between the high-end audio community, which is all about exotic and very, very expensive 2-channel systems, and the home-theater community, which is focused on Dolby Atmos, 11 or more speakers, and more, more, MORE subwoofers. Both communities are reflected in the homes of enthusiasts: one room for "real" music, with top-quality 2-channel rigs, and another room, in another part of the house, with an AVR-focused video setup, with 5, 7, 11, or more channels. The quality of conversion from 2-channel music sources to multichannel, using these AVR's, to be honest, is pretty poor, and far below what we were listening to in the days of quadraphonic sound. Dolby Pro-Logic II (music mode), in particular, barely sounds like surround or quadraphonic at all.

Moving away from the cultural to the technical side, the lack of interconnection between the high-end world and home theater is also striking (and annoying). Most AVR's have only three flavors of input: S/PDIF, which is 2-channel PCM (or used for lossy-compression codecs), 7-channel analog, or HDMI. HDMI is not friendly to specialist manufacturers, with a $20,000/year license fee, and a continually changing HDMI specification (which is driven by the continual upgrades to TV sets).

On the other side of the fence, over in audiophile land, the legacy interface is S/PDIF (with no support for the lossy surround-audio codecs used in TV soundtracks). The modern interface is USB, which supports high-res PCM, high-res DSD, and multi-channel PCM and DSD. I have not found ANY device which bridges the two worlds, translating between USB and HDMI, or between ADAT and HDMI. From what I can tell, HDMI is a walled garden that is aimed at consumer-only formats, closed to those who can't pay the annual fee, and only responsive to the largest Asian manufacturers. USB is an open format, and is data-agnostic. But good luck finding an AVR that has a multi-channel USB input. The only way I can think that might work would be something like a dedicated Raspberry Pi computer with USB multi-channel in, and HDMI (uncompressed) out. Not that I'm volunteering for that project, but a brave soul might try it. But maybe the HDMI licensing team might attack an open-source project like that: I don't know.

Surround sound music has fallen into the cultural and technical hole between the two camps. The high-end folks, where I've been hanging out for the last 25 years, either have contempt for mass-fi AVR's and the mad proliferation of channels, or have completely separate music and theater rooms. So where does multi-channel music go? Does it get truncated ("downmixed" in the ugly parlance of home theater) into 2-channel so it can be heard on the big rig where "quality" music is heard, or does it go through the mass-fi AVR next to a dark TV set? For that matter, a dedicated home-theater room with a serious HT setup, a dark projection screen, and nothing to watch. Not an ideal choice for surround recordings, is it?

The other problem, aside from culture-wars and lack of physical interconnection, is the very poor quality of decoders (or "upmixers") to expand 2-channel sources into 4, 5, or more channels. I'll be blunt: Shadow Vector, which dates from 1974, was far superior to Dolby Pro-Logic II (music mode), or DTS Neo:6. DPL-II is slow, diffuse, and the impression of an overall sense of space is very dim. DTS Neo:6 is thankfully quicker, but there are tonal artifacts that are not so pleasing. I can see why AV reviewers are less than impressed with the quality of 2 -> N conversion… what's on the market is pretty poor, inferior to what we had in 1974, which is not a good look 45 years later. That's why I'm looking forward to auditioning the Involve Audio Surround Master V2, which is a $600 gizmo from Australia, or Malcolm Lear's all-software SQ and QS decoder. Either or both will almost certainly sound much, much better than the home-theater stuff we have now.

David Robinson, our gracious editor of PF, has stirred the pot with me by mentioning the exaSound e38 eight-channel PCM/DSD DAC. I heard this unit at the Rocky Mountain Audio Festival a couple of years ago, with multi-channel DSD, Bryston amplifiers, and 5 Magnepan speakers. This was the first time I heard multi-channel as good as what I heard at the BBC all those years ago. Natural, with a very realistic "you-are-there" sense of space, NO distortion on the climaxes (which is super rare on classical recordings), and an effortless sense of being right there in the auditorium. That's what Shadow Vector did with a half-decent recording, and it didn't have to be SQ-encoded; stereo was just fine as long as the recording had a good spatial quality. Hearing this again, from multi-channel modern DSD recordings, was a total delight. And the particularly wonderful thing about good surround is that it's obviously better than 2-speaker stereo, even to a non-audiophile. The sense of listening through a proscenium, or a "soundstage" is completely absent. Instead, You Are There. In that sense, it's not like stereo at all… you are no longer in your listening room, but somewhere else. The listening room just disappears if the surround synthesis is working the way it should. Oddly enough, you hear this before the music starts, as the recording ambience fills the room. It's a little startling at first, then you get to expect it.

Here are some fun and interesting things to come. The Australian-made Involve Audio Surround Master V2 offers SQ and QS decoding for 4 and 5-speaker setups, and QS in particular is ideal for stereo to quad synthesis. In fact, I've heard plenty of stereo recordings that actually sound better in quad than official SQ or QS recordings. There's Malcolm Lear's dedicated computer that will have both SQ and QS decoding (all in software, so no physical switching required), and possibly the famous BBC UHJ matrix, which they used for a number of classical recordings in the late Seventies. (Alan Parson's Stereotomy is reputed to be in UHJ format… it does have strong surround content when played in DTS Neo:6 mode).

And for modern content, whether PCM or DSD, there's the 8-channel exaSound e38 DAC. This approach bypasses the AVR pre/pro completely, since the exaSound e38 has a built-in volume control (with no loss of resolution or quality at reduced volumes, a built-in feature of the ESS Sabre converters). There is a surprising amount of modern PCM and DSD surround content available as downloads (which is where the USB input of the exaSound comes in). I already own an exaSound e20 DAC, and they are pretty impressive DACs that sound like DACs at double or triple their price point.

In an ideal world, there would be AVR's with "Involve" and "Shadow Vector" algorithms built in to the receiver (and the Shadow Vector patents are long expired), but in the meantime, here are some interesting choices:

Involve Audio Surround Master V2 (SQ and QS decoding and stereo enhancement, with analog inputs and outputs): HERE

exaSound e38 Mark II 8-channel DAC (multi-channel PCM and DSD from the USB input): HERE

Discussion thread on Quadraphonic Quad forum: HERE

Shadow Vector patent: HERE

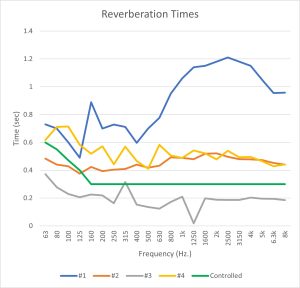

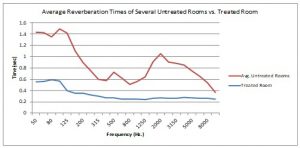

P.S. Here's a little warning for the surround-curious: One potential problem with multi-channel (which I found out in the Shadow Vector days) is that poor quality surround causes listening fatigue, and it's much worse than stereo. Just as stereo demands matched channels and half-decent speakers to not sound unbalanced or create an unreal "hole-in-the-middle" effect, surround demands peak-free speakers with reasonably smooth dispersion and no abrupt tonal differences between front and rear. If these aren't fulfilled, surround just causes annoyance and a desire to turn the rear (or side) speakers off. The popular crutch in the home theater world are simple auto-EQ systems like Audyssey, but these really can't mask a poor-quality loudspeaker. Auto-EQ systems like this often make good speakers sound worse, since the EQ makes the impulse response worse, not better. (This is where Dirac Live offers a genuine improvement for good loudspeakers.)

The answer is Quality All The Way… don't get speakers, for any part of the room, that don't sound at least reasonably good playing music as a stereo pair. That applies to the Center speaker, too. Does it sound musically acceptable playing your favorite music in mono through it, or not? If it's peaky or fatiguing all by itself (and I found most Center speakers are), get rid of it. All 4, 5, or 7 speakers need to sound good by themselves; surround is more demanding than stereo, not less.