Part 1: TECHNOLOGY

Or why a recording is not a document and what does it mean

DIGITAL SOUND RECORDING – method of preserving sound in which audio signals are transformed into a series of pulses that correspond to patterns of binary digits (i.e., 0's and 1's) and are recorded as such on the surface of a magnetic tape or optical disc. ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA | www.BRITANNICA.com; accessed: 07.01.2021. ⌋

From the very beginning, as soon as man started recording sound, we had ambitions to create what was recorded. Although the recorder was conceived as an office aid—a Dictaphone—that is, a 'documenting' device in the strict sense, the recording process was an undertaking focused on presenting reality in a way that was allowed by the technical possibilities and as seen by the person responsible for the recording.

Although this process was almost perfected in the analogue era, it was only digital technology that made it possible to create a musical event on an unprecedented scale. For this to work, audio engineers and producers had to have devices at their disposal that would enable them to copy tracks without loss—it was mainly about noise. Such a possibility was made possible by digital technology, and more specifically digital reel to reel tape recorders.

The "first wave" of tape recorders with spinning heads, with devices from Nippon Columbia (Denon) and Soundstream, we wrote about in the article entitled Digital technology in the world of vinyl. Trojan Horse or a necessity? (High Fidelity № 155, March 1, 2017; see HERE), happened in the 1970s. They had a little impact on the industry and while they did produce excellent recordings, they did not change the way we think about the record as such.

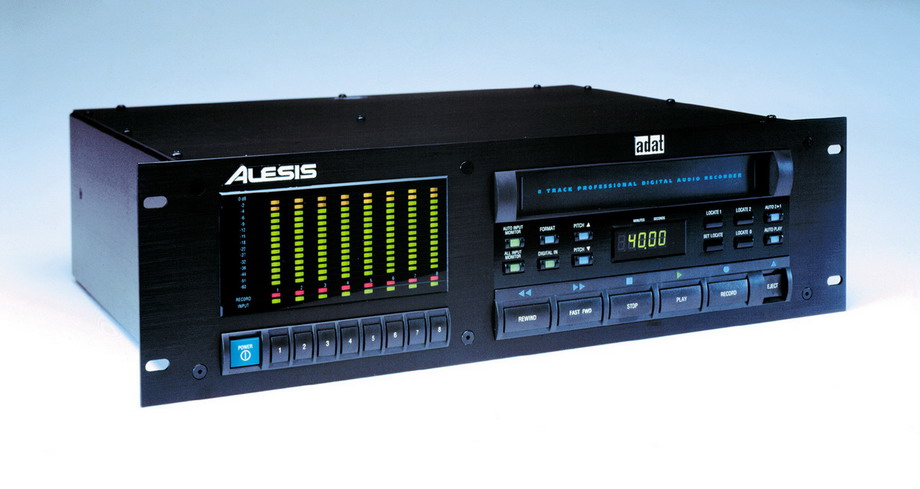

Alesis ADAT was the first affordable digital photo recorder. Photo Alesis press materials

The second battle with analogue tape recorders, but also with each other, was played by two systems with fixed heads, or the "second wave:" Mitsubishi digital tape recorders with the ProDigi system and Sony with the DASH system (1980s). We covered them in a three-part article MITSUBISHI ProDigi. ProDigi digital reel to reel - from X-80 to X-850 (Part 1 HERE, Part2 HERE, Part 3 HERE HF № 193. May 1, 2020, May 16, 2020, № 195. July 1, 2020). And they brought a truly new thinking about what is possible and what is not possible in the studio.

However, they had two drawbacks that eliminated them relatively quickly from the landscape—they were very expensive and did not allow for immediate editing. The first one was remedied by an Alesis technique called ADAT. Presented in 1991, it was based on inexpensive tape recorders and cheap carriers; S-VHS cassettes. These tape recorders were a gateway to another world for recording studios and democratized this industry—from that moment high-class recording could be made not only in large, expensive studios, but also in a small home studio, the so-called "Project Studio."

The history of this transformation can be found in the three-part article Alesis ADAT; Thirty years of a digital recorder that revolutionized the music industry (Part 1 HERE, Part 2 HERE, and Part 3 HERE).

But even the ADAT was a linear recording system, in which it did not differ in any way from the first cylinders and gramophone records. The breakthrough came only with non-linear recording systems. Today, every cell phone is this type of a recorder, every computer and tablet. However, in 1994, when the RADAR (Random Access Digital Audio Recorder) was introduced, musicians and recording studios got their hands on a tool that changed the rules of the game.

I will not exaggerate if I say that it was a technique that changed reality to the extent comparable to the introduction of eclecticism, and then of a tape to recording, which directly precedes the ubiquitous digital workstations (DAW) and Pro Tools systems. This will be the second part of the article you are reading.

Before we get down to that, I would like to discuss with you an issue that in the world of music is something so normal that it is "transparent," and in the world of perfectionist audio, or—as it is said—an audiophile one, is a distorted subject, namely about the way to approach the recording as if it was a "document."

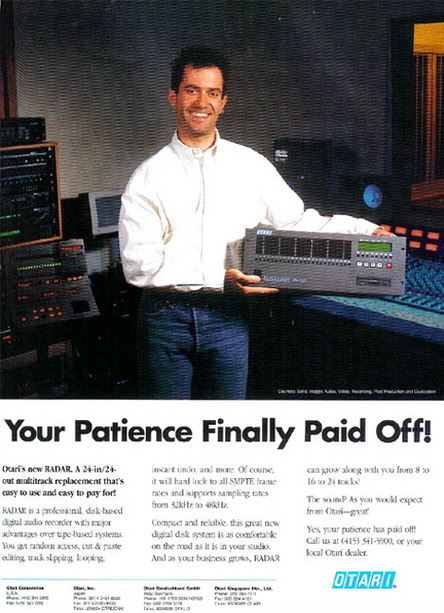

Otari RADAR – the first version of the recorder. Photo Otari press materials

In the next, third part, which I invite you to read next month, we will look at six CDs that have been recorded using the RADAR system, we will discuss how this technique was used, and we will also look at the sonic results. There will be various albums of different music genres and by different artists, which hardly anyone associates with this type of technique. Let me invite you to the world of non-linear audio signal recording, which was the beginning of the latest and—so far—the last revolution in the way of recording music, for better and for worse.

STUDIO AS A MUSICAL INSTRUMENT

The history of the recording studio as a place where "new worlds are created" is the story of breaking down successive technical barriers on the one hand, and on the other hand, a story about the role of people involved in this process. First, there were efforts to best match the horns used for acoustic recordings to a given band, instrument, singer and a specific type of sound. After switching to electric recording, different artists got their chance, ones who were not recorded in the acoustic era.

The next step were magnetic tapes entering studios in 1945 - 46, which made it possible to edit material on a scale that was not possible before. And even if the Les Paul did wonders with the sound-on-sound technique of recording consecutive acetates of records using two other acetates and another layer of guitar sound, these were just fittings for what editing the tape made possible. And yet, in the creative approach to recording, only the multitrack technique brought a permanent change—first there were three, then four, eight, sixteen and finally twenty-four tracks (1950s, 60s and 70s of the 20th century, respectively).

The "new" one, however, brought its own problems, which made its mark on artists, and the most important was the noise of the tape and distortions. If it were "documentation" of the event, there would be no problem. However, the multitrack technique based on magnetic tape gave the industry a powerful creative tool that was eagerly used. Many musicians became producers, and instead of spending a few days in the studio, rock bands almost lived in the studio, preparing the album for six months, a year, or longer.

The answer to the problems of "analog" was digital recording. The first commercially available digital LP was released in January 1971 by the Japanese label Nippon Columbia (Denon). This tape recorder was based on a video reel transport and recorded sound with a resolution of 13-bits and a sampling frequency of 32kHz. The whole decade of the 1970s was spent on improving sound quality (higher resolution and sampling frequency) and increasing the number of tracks.

This first generation of digital recorders, however, had an inherent weakness which was the helical recording—the recording was performed by rotating heads. The answer to this were tape recorders with fixed heads. Two solutions have gained popularity—ProDigi by Mitsubishi and DASH by Sony. They divided the studio market among themselves, coexisting there with analogue tape recorders.

As might have been expected, the solving some problems brought new ones. Apart from the technical aspect, the most important brake in the dissemination of digital technology was the high cost of this type of tape recorders and the complicated operation. Only the richest recording studios could afford it, with the active presence of people with technical talents during the recording.

This situation was solved by the introduction of Alesis ADAT tape recorders in 1991. They were inexpensive, eight-track digital tape recorders, recording PCM 16/48, and then 20/48 signals, on widely available, cheap S-VHS cassettes. It was a tool that democratized the process of recording albums and, while at the same time it lowered the average sound quality, it also unleashed creativity and democratized the recording process.

All the recording techniques mentioned, from a wax roller, through a vinyl record, a tape recorder and digital recorders, to an ADAT tape recorder, were linear techniques. This means that the signal is recorded on the medium in a "continuous" manner. Editing such recorded material is difficult, although not impossible. A real revolution in the method of recording albums and at the same time in the way recording studios functioned was brought about only by the introduction of the non-linear technique - this is what this story is about.

Press ad for the RADAR system from mid-1990ties. Photo Otari press materials

The first, fully mature system, and at the same time the most popular, was RADAR developed by the Japanese company OTARI, previously involved in analog tape technology, and then in the development of digital tape recorders of the ProDigi system. This system made it possible to edit the material and manipulate the sound on an unprecedented scale. Steve Levine, in the 1990s producer of most albums of music known as Britpop, spoke of this "invention" like this: I don't like computers and playing with the mouse, because in my opinion this type of technique can be an obstacle in the relationship between the artist and the producer. But with RADAR (Otari HD recorder) it was different—the controller was lying on the mixer and you could feel it, and at the same time it looked like a tape recorder, so people did not even think about it. He was just there, recording whatever you were doing with the band.

Samantha Bennett, Modern Records, Maverick Methods, p. 122.

However, anyone who would say that in this way the "noble" art of recording a "real" musical event has disappeared and that the time has come for "produced" or "constructed" music would be wrong. This is because there was nothing to disappear—something like this really existed in the history of mechanical sound recording.

A DOCUMENTARY MYTH

One of the longest going myths about recorded music is related to the belief that an album (on a roller, tape, in a file—the medium does not matter) is a "documentary" showing musicians in the studio or on stage in a manner "consistent with reality." Some labels, with Sheffield Labs., Naim Label and Chesky Records as the main representatives of this trend, have tried (Chesky still does) as much as possible "to stop the time" by recording the material without editing, with the simplest possible microphone set. These were, however, activities which, by limiting the interference in the recorded material, limited the creativity of musicians and music producers.

These types of recordings are close to a "documentary." And using the phrase "documentary" for a recording refers to other areas of art—photography and film. Nowadays, however, there is a consensus that there is no such thing as a "documentary," because everything that comes out of the hands of a man is a derivative of his choices, such as the choice of frame in a documentary photo, and even the way photos are processed. There is an agreement that everything is a creation and in this context even the "purest" recordings are an expression of the choices of the people involved.

The ability to interfere with recordings, to edit them attracted musicians and engineers from the very beginning since the first sounds were recorded. What other than "producing" a recording is placing musicians at the right distance from the horns transmitting the sound to the acetate cutter? How else to explain the work done by Les Paul in adding subsequent layers of material to acetates?

This may come as a shock to many, but even labels known for their excellent sound quality, whose recordings seemed to us to be the product of one magical moment, edited the tapes, often in a way that resulted in an effect that was nothing like what actually took place in a studio.

We know a lot of examples of editing, both from the times of monophonic and stereo recordings, and even more so with multi-track recordings. The creation of an album, because this is in fact the process we are talking about, it happened with all the artists and almost all the titles, including the greatest ones. Ed Michel, preparing the material for the Miles Ahead by Miles Davis, said: Teo Marcero could not go back to the cut A tape—the tapes were labeled A and B and the stereo tape was labeled C—because the A tape was cut so badly that it was thrown away. Theo only "by ear" could try to say what was used, but it was an incredibly difficult task. There were a lot of takes that we recorded.

Michael Jarrett, Pressed for All Time, p. 50.

The studio reality was different than what purists would like it to be. Producers, and then artists as well, recognized the studio as another instrument that broadens the creative possibilities. Therefore, there is no such thing as material recorded and released without editing. The degree of editing the recorded material varied between studios and producers, it was different in the acetates era and it is different today, but it has always been present.

While looking for material for re-editions, Michael Cuscuna, the producer responsible for the re-releases of Blue Note records, recalls that he was surprised how few alternative versions of the tracks he could find. Besides, those that had not been used before were, according to him, failures and it is was a good thing that they were not included on the original albums. He explains this by the fact that the recording sessions of the Blue Note label were well prepared and preceded by rehearsals. Thanks to this, when "you got the master tape, it was a masterpiece" (Op. Cit., p. 103).

It doesn't mean that taped were not edited, they were: If Alfred (Lion, founder of the Blue Note - ed.) heard a great trombone solo in one of the takes and he liked the pace which he could then paste it into another take where everything else was great, sometimes he did just that. It was a kind of a "broadening". It was also obvious that if something at the end of a song got screwed up, and it happened really often, you could paste a different ending. And that's it. (ibid.)

As you can see, 'recording as a documentary' is a figment of the imagination. From the choice of recording place, microphones, recording method, to post-production, all this makes the album an artistic work that is not the same as a live performance. What's more—it is not meant to be. It is supposed to be something else—an artistic work that has its own truth, which is to evoke specific emotions in a listener. If it is works, then it is a job well done.

Having said that, let's add that the edition was part of the recording technique in every musical style, from classical to jazz and rock, culminating in popular and club music. Polish music is also part of the history of editing, as Zbigniew Holdys, the founder and leader of the Perfect band, reminded us of in his column some time ago. As he says, in 1984 he stopped playing. At that time, he was friends with Walter Chelstowski, whose basement was used by a beginner, then still completely unknown band:

They played various things that did not bode too well. One day they played their song for me and it was very nice. Soon Walter announced that they had just recorded this song and wanted me to listen to it. I dropped in to the studio. It was worse than what I'd heard in the basement. I told Walter, "Get six hours of studio time and an audio engineer, we'll remix it and see." The next day I came with my guitar, huge fiberglass drum cases. I was accompanied by my friend, the great drummer Wojtek Morawski.

We locked ourselves in the studio. We started working. I divided one recorded part of the guitar into several seconds long fragments (physically the tape was copied to the other tape recorder and cut with a razor blade) and scattered it in a wide stereo panorama—now there were four guitars, each sounded different. I threw some parts out, I added some chords and—most importantly—we added a steady rumble of those drum cases, which Wojtek was hitting with his fists. A demon in a leather was walking through the city. Time ran and we finished the laboratory work at the very last moment. There were no computers then. It's a miracle that it worked out.

Zbigniew Holdys, Wolność tanio sprzedam, Newsweek 16-22.08.2021, p. 33.

The band in question was Aya Rl, with Paweł Kukiz on vocals, and the song is Skóra. In this version it was presented to Marek Niedźwiecki, a journalist who ran the program "Lista przebojów Trójki" on the state radio, and then for a few weeks it occupied the first place—and, let me remind you, it was the most influential, most important music radio broadcast in Poland.

What Hołdys described above is the work of a recording producer at its best. Their role has changed over time, going from an undefined position, through a person responsible for booking a studio and snacks, to a person arranging the repertoire for an album, inviting musicians of his choice and finally creating music, lyrics and most often also playing on it and recording it. Hołdys was not so much a "remixer," but a co-creator of the song, a hit of the mid-1980s in Poland, which—this is my opinion—he created it almost from scratch, editing the original material and adding more tracks, without the presence of the band.

Manipulations to which the audio signal is subjected in the studio belong to an order other than "technical," they are part of the artistic, creative process. If they are perceived by the listener as an "event," finished and complete, it means that the producer did his job well. And it happens even with material in which incredibly deep interference has been made.

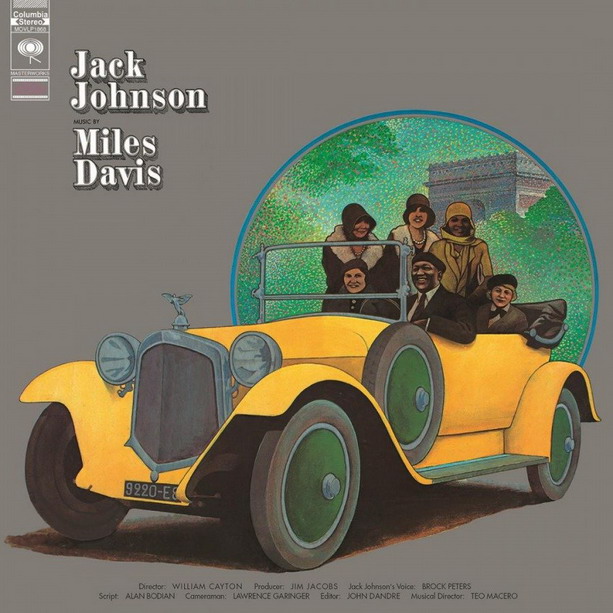

This is how the words of the editor of the Stereophile magazine, Herb Reichert, who wrote about the Miles Davis album in his review of the Marantz Model 30 amplifier should be perceived: The carefully prepared by Mobile Fidelity re-edition of Miles Davis' Jack Johnson (LP, MFSL 1-440), which is more powerful and more vivid than the original release, is an album that I come back to for inspiration. It is a pure, direct artistic testament by which Reverend Miles carries me a personal service, sharing his desire for something real and permanent using only notes with glorious reverberation surrounded by the all-fueling sounds of a heavenly band.

Herb Reichert, Marantz Model 30. Integrated Amplifier, Stereophile, p. 53.

Reichert is of course right—A Tribute to Jack Johnson, released by Columbia in 1971, is a brilliant album, although it is one of Davis' lesser known works. He is also right about his artistic message, correctly recognizing the direct emotional "transfer" of energy from the artist and his band to us. This short excerpt, however, shows something I talked about above—namely that a successful musical piece has an inner truth that permeates the listener due to the means that have been used to achieve this goal. Sometimes even, as in this case, if the means in question are in opposition to how the work is received.

A Tribute to Jack Johnson is an album "constructed" entirely in the recording studio

It is so, that the album in question is not a documentary of a recording session, at least in the common understanding of this process. It was "constructed" by the producer, Teo Macero, at the behest of the trumpeter. The command was simple: "I'm going to California. I have $ 3000. I'll give you $1500 and you'll put together some music from the tapes in the archives." This is an authentic story, brought up by Macero, who worked with Davis on some of the most important albums, which he told to the already mentioned Michael Jarrett.

Work on this "musical testament" consisted of searching tapes with previously unpublished material, cutting them, gluing them and there it was. There are, as he says, a lot of repetition, which makes the album sound today as if it was a harbinger of fusion music. This is one part of the story. The second one was added by the musician himself, who started performing these songs on stage at the same time.

It was a characteristic feature of these concerts that Davis moved from one track to the next without a pause as if they were a whole. The audience and music critics thought that this was his new style, which was confirmed by the aforementioned album. And it was the other way around—this was life imitating art, and the authors of the album, on an equal footing, were the artist and the producer. As Jarrett says, "A good editor can make a great book even better. A bad one can ruin this book "(Michael Jarrett, op. cit., p. 143).

There are plenty of examples like this one. I would even say that there are as many of them as there are good albums. The best ones were heavily edited, and the lesser ones were often the ones without any editing. George Avakian, one of the most important American music producers, responsible for the albums of artists such as Louis Armstrong, Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, Dave Brubeck, Keith Jarrett, Sonny Rollins, Paul Desmond, and Edith Piaf, says that this is not about " aesthetics" but "business." The thing is that record labels with small budgets published everything "as it goes" without trying to extract from the recordings the artistic content that was hidden in them. He even talks about obvious mistakes that were "let go" in this way.

Isn't it so that the so-called "audiophile recordings" are for the most part boring and artistically poor for this very reason? Maybe they are artistically insignificant, because they lack "editing," they lack a good music producer—in the name of "sound quality" they are not edited?—It's just my intuition, but supported by what I said earlier, it has a chance to turn into something stronger, into a belief that no editing means the lack of an important layer in the art of recording music. Recording editing is not so much a technical—but also an artistic activity, it should be clear by now. To be good at it, you need to know what you are doing and be both a technician and an artist.

So the tapes for the best albums were cut, copied, short reverbs were pasted in to cover the cuts, the speed of the tapes was adjusted to synchronize the "master" tape from two tape recorders—just to match the tempo - the tape was reversed, short musical elements were loaded onto the already recorded track (so-called "punch-in"), material was recorded on the already existing material ("sound-on-sound"), the number of tracks was repeatedly "reduced" by ripping four, and then eight tracks into two, in order to have more free tracks—in a word everything was done to make the album artistically significant.

RoXdon set, one can buy here and now, used to cut and paste together 1/4'' tapes. Photo Runway Pro Audio press materials

These actions have given us such masterpieces as Kind of Blue by Miles Davis (1959), Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band by the Beatles (1967), Pet Sounds by The Beach Boys (1966) or In the Court of the Crimson King by King Crimson (1969). The problem that all producers and recording engineers had to deal with was the method of recording—first on acetates, and then on a tape.

The process in question was extremely time consuming. While in the times of monophonic recordings, and later stereophonic and three-track recordings, i.e. from the mid-1940s to the end of the 1950s, the thing was to record many takes, select the best fragments from them and paste the final version together, along with increasing the number of tracks, so with the expansion of the artistic palette that was made available to the artists, things began to get complicated, and the production of recordings, their mixing and mastering took more and more time. The solution to this problem was brought only by digital technology.

RADAR

In October 993 at a convention of the Audio Engineering Society in New York, the Japanese company Otari presented the first hard disk recorder in history (this information comes from Wikipedia—Samantha Bennett says that the first presentation took place in November 1994 in San Francisco): RADAR, with the name being an acronym of Random Access Digital Audio Recorder

It was not the first computer memory device to record audio, but it was the first complete multi-track system that allowed almost unlimited real-time editing of material. This system was designed by the Canadian company Creation Technologies of Vancouver, on the initiative of Barry and Jane Anne Henderson, and Otari was granted an exclusive license to it.

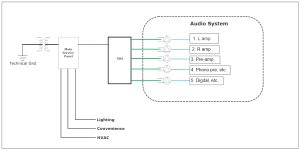

The recorder consisted of two parts: a module with a processor and hard drives and an RD-8 remote control. The former was bolted to racks somewhere in the recording studio, and a controller with LED VU-meter indicators was placed on the mixing console or next to it. The processor module was similar to ADAT tape recorders—it was compatible with them. The user could synchronize them, thus increasing the number of available tracks. The system also made it possible to edit the material, although not yet on the scale that characterizes DAW stations such as Cubase or Pro Tools.

VERSIONS

The first version of RADAR (I), available since 1994, offered 24-tracks with PCM signal recording with a resolution of 16-bits and sampling frequency of 32, 44.1 or 48kHz. The system cost US $ 24,000, so it was as affordable as ADAT recorders, knocking out all Sony and Mitsubishi digital recorders in this respect. As a result, it has become the basis of both professional and home studies, as well as stationary and mobile systems.

RADAR II offered 24 bit recording on 24 tracks. Photo Otari press materials

It was developed and improved over the years. And so, in 1997, RADAR II was introduced, offering 24 tracks with 24-bit recording on a single disk and allowing several devices to be combined into a 192-track system—as you can see this evolution resembles the changes that ADAT tape recorders have undergone. Systems I and II were sold until April 2000 with the Otari logo and were distributed by this corporation all over the world. At that time, the rights to the invention were acquired by the Canadian company iZ Technology, the heir of Creation Technologies of Vancouver.

From this year forward, RADAR II was sold under a new name, and from 2000 the device could record a signal sampled at 192kHz, albeit with a limited number of tracks, and it was named

RADAR 24

It had a more powerful processor and ADAT I/O connection. Another change took place five years later. In 2005, RADAR V (V = Vee) is launched, where all tracks can be sampled at 96 or 192kHz.

A completely new platform, called RADAR 6, was launched in 2012. Launched in October, the device was smaller, had a touchscreen and offered SSD recording. A/D and D/A converters have also been improved. It was a year in which around 3,000 iZ Technology recorders were already in operation all over the world. In 2015, there was an important change and in the RADAR Studio model, users received an editing platform that integrated the recorder with digital DAW workstations.

Reception RADAR caused a huge change in thinking about a recording studio. For the first time, no tape was needed for recording, and the sound material could be edited non-linearly, which was later developed by DAW stations. New technologies are reluctantly adapted in recording studios - the larger the studio, the greater the resistance. So despite the new possibilities, this invention "caught up" only by the end of the 1990s, when the first hits recorded in using this solution stormed the charts.

As Bennett writes, the resistance came from the fact that at the time recording studios preferred to incorporate new devices into the existing structure rather than replace them with new ones. So in one place you could find analog, digital ADAT and RADAR tape recorders, next to Pro Tools systems. In the chapter of his monograph entitled Recording to Hard Drive. Producing Digitally, 1991 - 2013 Jarrett writes that many of the recordings he discusses were not digitally recorded at all, and even if they did, many sound engineers treated digital tape recorders and hard disc simply as an "improved analog tape" (p. 226).

This hybrid approach was then translated into specific productions and is the basis of many albums. In such environment, albums of artists such as Pet Shop Boys, Bob Dylan, Blondie, U2, Everything But The Girl, XTC, Mike Rutherford, Depeche Mode (live recording) and Panthers were created. The studios that used them include PWL, Factory Sound, Master Rock, and producers Ray Hedges, Nick Patrick, Craig Leon, Daniel Lanois and Mike Tildsley. Ronald Kirby points out that among the users of RADAR systems of various types, American studios prevailed (more in: The Evolution and Decline of the Traditional Recording Studio).

Craig Leon, the producer responsible for the sound of, among others, Ramones, Suicide and Blondie, when asked about the sound of tube devices recorded on analogue and digital tape, said: […] I do it in parallel. On the Blondie album (No Exit, a RADAR recording - ed.), for which I recorded many things in parallel in analog and digital format—I shuffled some elements from the analog system and edited them digitally. Sometimes I even used analog drums for the verse, and digital drums for the choruses. It's a subtle change, but it grows with the many instruments in the track.

Howard Massey, Behind The Glass, p. 228.

The combination of several different technologies also allowed for heavier editing of the material by the musicians. Dimebag Darrell, guitarist of the American band Panther, says that his father drew his attention to this technology, saying: "With it you can do anything you want. It's easier than using an old tape and putting the pieces together. You can do all this "in a box."" As a result of this suggestion, Reinventing the Steel released in 2000, was recorded on the 48-track Otari Radar system.

RADAR 24 system. Photo iZ Technology press release

So the music industry got a new tool, thanks to which sound engineers could give up tapes, both digital and analog, and could also incorporate them into existing systems - including those with tape recorders. RADAR offered simple, non-linear editing with direct access to any moment in the recording and any track, and later versions also integrated with DAW stations, which increased the editing possibilities to infinity. This was more than the makers of previous digital audio recording systems could have dreamed of.

And yet this was not the most important thing in its reception. As Bennett says, in the case of the Otari digital recorder, what was more important was not what it was, but what it wasn't. First of all, it was not a computer, and these were difficult to use and unreliable at the time. Nonetheless, it was operated in a similar way to an analog reel-to-reel tape recorder and was understood that way by many sound engineers and music producers.

In support of this thesis, the researcher quotes Mark Howard, producer of U2, Bob Dylan, REM, etc .: I was frustrated with the usage of a mouse. And then you had a guy on your screen saying something like, "Okay, you can do this or that, blah, blah ..." I don't know, maybe it had something to do with feeling out of control over the process [...], or it was about it, you had to say, "Okay, we're going to start recording, but first we have to reboot the system." Something like that clips your wings, and such situations happened to me as well. [Otari RADAR] is incredibly trustworthy and it allows me to do everything that Pro Tools offer, maybe even faster, and I think it sounds better.

David J. Farinella, Producing Hit Records. Secrets From the Studio, Schrimer Books, Londyn 2010, p. 122.

Gaute Barlindhaug, in an essay entitled Analogue Sound in the Age of Digital Tools, points out: […] digital technology, on the journey to analog sound, helps build appreciation for analog aesthetics. This should not be seen as merely an act of nostalgia, but rather as a feeling that what really makes a given technology innovative is the context in which it is used (p. 90).

If we look at the statements of sound engineers and producers from that time, it is from the mid-1990s to the end of this decade, what would strike us would be the belief that the RADAR digital systems had an "analog spirit." Many of them even gave up computer systems, sticking to the seemingly inferior technology. This is mentioned by Craig Leon, a music producer whose name can be found on many Blondie albums, starting from their debut in 1976. As he says, on the No Exit from 1999, he tried to capture the aesthetics of the 70s using modern tools: The best thing about RADAR is that it's a technical device that doesn't sound digital. This is important to me because I love the old analog sound and could never work in a completely digital domain. I certainly couldn't digitally record the drums because I don't think the digital is able to offer adequate depth and clarity in the treble. But for everything else, we used the RADAR system.

Sue Sillitoe, Craig Leon: Recording the News Blondie album, p. 158.

RADAR Studio system. Photo iZ Technology press release

Another reason for the popularity of this digital recorder is indicated by Daniel Lanois—the producer whose work we can hear on U2's (Joshua Tree 1987, Achtung Baby 1991), Peter Gabriel's (So, 1996, Us 1992) or Bob Dylan's (Oh Mercy 1989, Time Out of Mind 1997) albums, in an interview for the American TapeOp magazine said, that in his opinion the most important in the approach to the recording medium is its mechanical, electrical and musical credibility.

AND FINALLY

And while RADAR today is just a historical curiosity, quite deeply buried in the dust of technologies that are no longer in use, it was considered at that time to be a much better sounding medium than Pro Tools systems. Ultimately, it is the latter that dominate the contemporary recording landscape, all other digital systems are no longer present, and analog systems are just a curiosity. However, you cannot pretend that you cannot hear what their users said, raising both the issue of sound quality, the feeling of being in contact with the analog medium, and its credibility.

Larry Levin, whose best known work is Pet Sounds by The Beach Boys, told Howard Massey in 2009: Just a few years ago, Herb Alpert called me and asked me to mix a few previously unreleased tracks for the [Lost Treasures] compilation album. We were supposed to do it digitally. However, since I didn't like the Pro Tools sound, we did it with RADAR, which I think sounds a lot like analog tape.

Howard Massey, Behind The Glass Volume II. Top record Producers Tell How They Craft The Hits, p. 40.

How do these declarations translate into sound? How did RADAR come into existence in the real productions of well-known albums? We will try to answer these and more questions in the second part of this article, dedicated to specific albums. We will look at the debut of the BLUR band, the unique solo project of Neil Young's entitled Le Noise, Reinventing The Steel by metal group Pantera, the first digital recordings of Blondie from No Exit, we'll listen to Bob Dylan's Time Out Of Mind, we will also meet the U2 with their No Line On The Horizon.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

David J. Farinella, Producing Hit Records. Secrets From the Studio, Schrimer Books, London 2010, p. 122.

Gaute Barlindhaug, Analogue Sound in the Age of Digital Tools. The story of the failure of digital technology, w: A document (re)turn: Contributions from a research field in transition, ed. Roswitha Skare, Nils Windfeld Lund, Andreas Varheim, Peter Lang Publishing 2007, p. 73–93.

Howard Massey, Behind The Glass Volume II. Top record Producers Tell How They Craft The Hits , Backbeat Books, San Francisco 2009.

Howard Massey, Behind The Glass. Top record Producers Tell How They Craft The Hits, Backbeat Books, San Francisco 2000.

Michael Jarrett, Pressed for All Time, Chapell Hill: The University of Northern California Press 2016.

Samantha Bennett, Modern Records, Maverick Methods. Technology and Process in Popular Music Record Production 1978-2000, Bloomsbury Academic, London-New York 2019.

Hugh Robjohns, Otari RADAR II. Tapeless 24-track Digital Recording System, www.SOUNDONSOUND.com, January 1999; accessed: 12.10.2021.

Jerry Vigil, Test Drive: The Otari RADAR Random Access Digital Audio Recorder, "Radio And Production", Dec. 1st 1994, RAPMAG.com; accessed: 12.10.2021.

Roman Sokal, Daniel Lanois: Recording U2, Peter Gabriel, Willie Nelson, etc., "TapeOp", TAPEOP.com; accessed: 12.10.2021.

Ronald Kirby, The Evolution and Decline of the Traditional Recording Studio, October 2007, p. 90; see HERE; accessed: 12.10.2021.

Samantha Bennett, Endless analogue: Situating vintage technologies in the contemporary recording & production workplace, Journal on the Art of Record Production No. 7, 2012; ARPJOURNAL.com ; accessed: 12.10.2021.

Sue Sillitoe, Craig Leon: Recording the News Blondie Album, "Sound on Sound", No. 2, December 14th 1998, p. 158, see HERE; accessed: 12.10.2021.

Herb Reichert, Marantz Model 30. Integrated Amplifier, Stereophile January 2021, vol.44 no. 1.

Zbigniew Holdys, Wolność tanio sprzedam, Newsweek 16-22.08.2021, p. 33.

Text: Wojciech Pacuła

Translation: Marek Dyba

Images: press materials | Wojciech Pacuła