[Joe Cohen is a long-time friend of Positive Feedback, and owner of The Lotus Group, a high-end audio company in California. Joe is married to the Jazz vocalist Daria, and has a deep love of music going well back into the early days of his life. I read an earlier, shorter version of his musical journey, and was attracted by it. I therefore asked Joe to extend it for the "Audio Discourse" section here at Positive Feedback.

Our musical journeys are really at the heart of what we love about fine audio and the audio arts, I think. Perhaps you have a story about your voyage in music and audio...if so, then you are welcome to share it with me here at PF: [email protected]. Who knows? It just might get published.

Joe's story is well worth hearing…read on….

Dr. David W. Robinson, Editor-in-Chief]

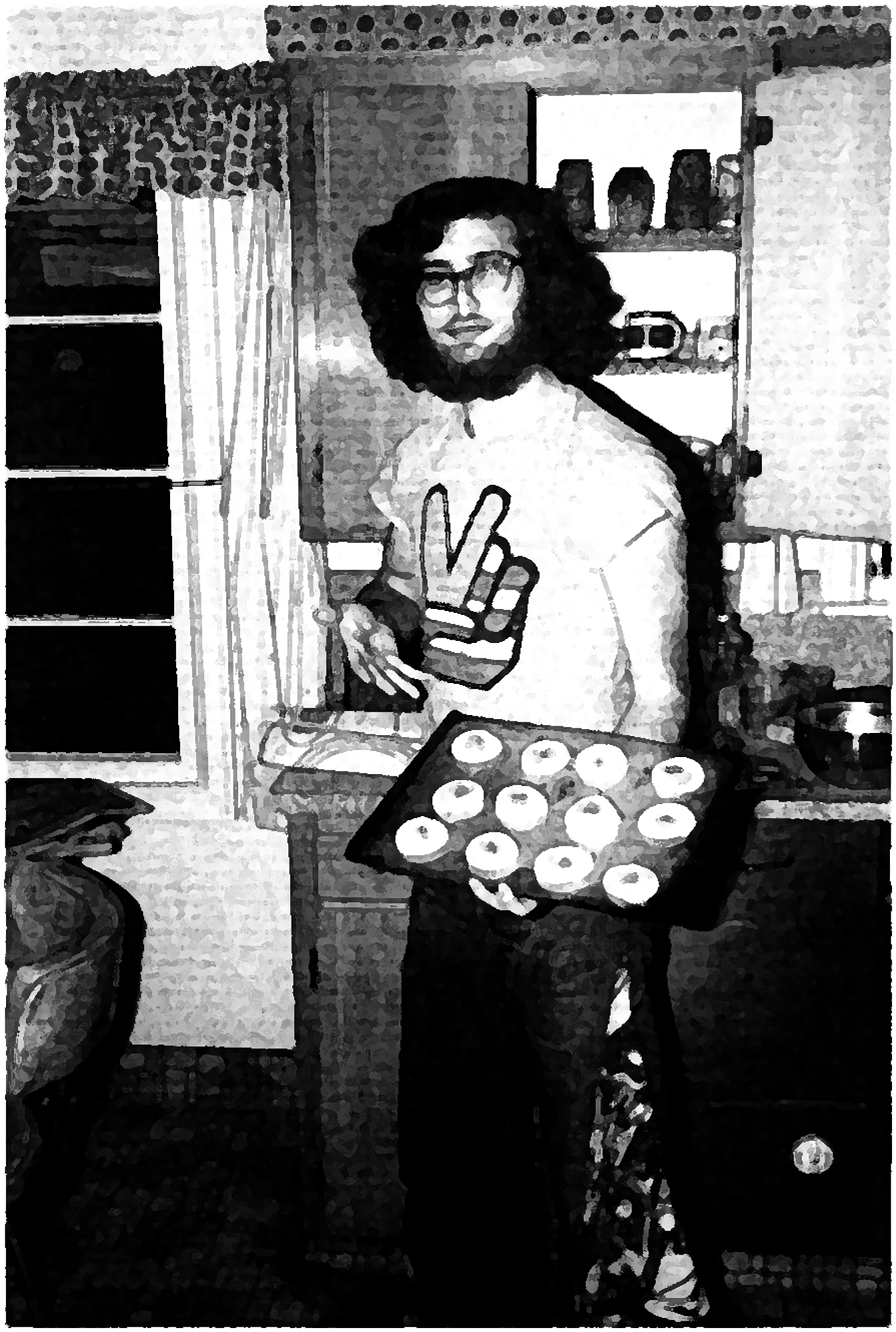

1965, my senior year at Central High: I used to catch a ride to school with Danny C in his new blue Volvo 544, the kind that looked a lot like US cars from the forties with their rounded front bumpers and tapering hoods, but a lot smaller, with a tall stick shift sprouting out of the floor like a crooked branch. Some kids had all the luck! Danny knew the clerk at Robbins bookstore and used to load books in his arms till they were spilling over and wink at his friend as he made his way out the door. Nothing seemed to faze him. I have to say he had balls. Danny's folks had a three-story house just around the corner from where I lived. The third floor was his domain with a door he could lock against the intrusion of unwanted parental attention. We used to go up there after school and smoke weed. It wasn't very strong, but we got high on the idea anyway. We used to lie on the floor and listen to jazz. This is where I was introduced to John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy, McCoy Tyner, Gil Evans, Bill Evans, Ornette Coleman, Art Blakey, Rahsaan Roland Kirk with three reeds in his mouth, Mingus, Monk and Dizzy. This was a visceral education—a seeping into the bones of a rare and strange elixir that exploded the confines of provincial West Mount Airy, Philly and introduced us to outer space.

One time he put on something completely new—Ravi Shankar and Chatur Lal. The recognition was powerful and instantaneous. The sitar's intense energy traced elegant designs of pure silver in the air while the tablas reciprocated with ever mutating geometric rosewood patterns. Inlaying each other, they traced a shining tapestry of pure bliss before me. This moment, more than any other, was to define the rest of my life, and I was helpless to stop it.

Music was something we knew when our bones were still soft, when we were more of a promise than a person. Language came eons later. The motion of a spiral nebula and the speed of a photon are two ends of a rhythmic scale that informs and propels us. We are literally cold hard stardust transformed into pulsating hearts whose sole function and purpose is love as we streak across the firmament and disintegrate like comets. In spite of any idea we may have of ourselves, this is reality, and music lets us in on the secret. The universe is musically aligned. Building pathetic parapets of sand in vain attempts to hold on to that which cannot be held onto, we deny ourselves the ultimate beauty from which we are made. When an artist wows us and leaves us breathless, he or she is holding up a mirror that exposes what already exists. In that world there is no attainment of perfection, but perfection is everywhere we look.

When my son was born, from the first moment, I could see he had a trajectory all his own. When I left Danny's loft that day, I had gained a new trajectory and a new thirst that could never be quenched, but only pursued.

1950, Loretto Avenue, Northeast Philadelphia: My mom in her green dress, minor key music playing in the background, the two of us dancing in sheer ecstasy in the living room.

1952, Nature Friends, Pennsylvania Dutch Country—a summer retreat rented by progressive young families: Our cabin was too far from the central bathrooms to go to at night so my brother and I had a coffee can to pee in. The dads played volleyball and pinochle. The kids ran around and begged their parents for a dime for strawberry milk or ice cream at the concession. I remember my mom giving me a bath in the sink in the ladies room and all of her friends cooing over me. Everyone would hang out at the pool. Sometimes people of German heritage used the same facility for beer parties. When our paths crossed, you could feel them bristling at the Jews invading their turf—a bit of a cold shower in an otherwise warm and nurturing environment. One day a trumpeter, Mr. Autry, a black man, played outdoors on a stage. I stood right in front, thunderstruck.

1965, New York City working as a "Plans Desk Boy" at the architectural firm that designed the Pan Am building: This co-op job from Antioch managed to murder any ambition I might have had to become an architect. Everything about the place was stultifying. Emory Roth and Sons were sticklers for punctuality, and never let us leave a second before 5:30 p.m. On the night of the great blackout that turned into a real blessing: The power went out at 5:28 p.m. I felt for the poor people stuck in elevators all over town. New Yorkers were never nicer. People appointed themselves as guardians to direct pedestrians away from openings they might fall into on the sidewalk. Crime was way down. Nine months later there was a huge upsurge in the birthrate. Hey, maybe we should have intentional blackouts now and then. Just sayin'.

I saw a posting for a sitar concert at a small auditorium in the United Nations complex. Mr. Om Prakash, a painter from Delhi performed. After the concert I asked if he could teach me sitar. He said yes. So I began to see him every week for about a month. On my fifth visit he answered the door said, "Oh, I forgot you were coming. There's no lesson today. We're going to meet John Cage. Would you like to come?" We drove to a modern low slung house in Stonybrook and hung out and made small talk with the owners. Mr. Cage didn't talk much, but he smiled a lot. We played poker. I won $2.47.

1966? Yellow Springs, Ohio My friend, an aspiring jazz trombonist, who later died of a heroin overdose: "We're going to hear Coltrane tonight in Cleveland. Want to come?" The festival was in a baseball stadium. People were sitting close to the low fence that separated the seats from the field, eating and chatting away loudly while Coltrane was blowing the heavens open. I put them behind me and leaned forward against the fence, thunderstruck.

Nikhil Banerjee

June 1967 San Francisco: Arriving in San Francisco for the first time from the east coast, my eyes were wide in wonderment. The sky was a shade of blue I had never seen before. It was as though life on the east coast was in black and white and California was in Technicolor! I was here to study sitar with Nikhil Banerjee at the American Society for Eastern Arts. Even before I had heard his music, I wrote to him asking if I could come and study with him in India. He replied we should meet at the summer school in Berkeley and discuss it. Before the session began an all-day concert was held at San Francisco State. On the agenda were concerts by Nikhil Banerjee, Ali Akbar Khan, Bala Saraswati the great Bharata Natyam dancer, Vishvanathan and Ranganathan—legendary South Indian musicians as well as revered Japanese and Indonesian musicians. Suzuki Roshi also gave a talk. Mr. Banerjee's concert brought me to tears. This was a level of sitar playing that was beyond anything I had heard. I went backstage to meet him after. Before I could utter a word, he said, "So, you have come."

In the fall of 1967 I traveled to India to study with Mr. Banerjee, but due to various twists and turns in my life arrived in Calcutta (Kolkata) many weeks before he was due to arrive. I went to the Ali Akbar College of Music and sat in Dhyanesh Khan's class. His aunt, Annapurna Devi*, was teaching there at that time. When she heard that someone had arrived from America, she had me audition for her and put me in her class. Some weeks later, when I heard she was leaving for Bombay (Mumbai), I went to see her in her apartment. She was teaching Rageshri to a small group of advanced students. Being in her presence and listening as the students played back the phrases she sang struck me to my very core. It was in no way different than having darshan with an extraordinarily powerful yogini. For that is exactly what she was.

I was extremely fortunate to be able to study with her in Bombay for a few months. I went twice a week at 1 PM. At that time the nameplate on the door to her apartment read Ravi Shankar. A young serving girl would bring me a Coca Cola and then I would play sapat (scales) for one half hour. She would be cooking in the kitchen, and then would come out and teach me a phrase in a slow gat (composition) for a few minutes and then return to the kitchen. After about an hour of practice I was served some tea and a potato pancake or samosa. Then she would teach some phrases in a fast gat. Occasionally while she was cooking, she would lean out of the kitchen and correct something I was doing. One time Hariprasad** came for a lesson. I also met her son, Shubho many times.*** He had a lovely and mild demeanor. One time she remarked that he had to decide if he wanted to get serious about sitar. Years, later I was saddened to learn of his early demise.

I didn't stay long in Bombay. I was living three train rides away from my lesson, utterly isolated with no friends to help sustain my spirit. It was an untenable situation and after a while I had to leave. When I went to her apartment in Calcutta she was reluctant to have me come to Bombay. I later came to appreciate that reluctance, but I was young and naive and completely taken with this music that was literally a gift from the gods. Perhaps in a different universe I would've been able to stay and become a true disciple, but I remain deeply grateful for her generosity. What I did learn was a small taste of a true foundation. I had found my way to the source and was blessed.

I continued studying with Mr. Banerjee in Berkeley nearly every summer. The Ali Akbar College had formed in Marin. He would have followed Khansahib to the college, but they were late in offering him a contract so rather than have no contract at all, he signed with ASEA.

I used to drive him around Northern California in an old Deux Chevaux on loan from a friend. We would visit friends in Canyon, over the hill from Montclair. Near the top we would always have to get out and push. One time, when we were getting gas in the car, Mr. Banerjee, opened his wallet inches from his eyes to see the denominations. As a child he had contracted beriberi during the man-made famine of 1948. His eyesight never recovered.

I invited Aashish Khan and Mr. Banerjee for dinner. Not thinking, I prepared beef. Mr. Banerjee asked, "Is this beef? We don't eat it, you know," then said, "That's OK, I'll eat it anyway."

When I took him and his brother-in-law to Tassajara. (Zen Mountain Center in Carmel Valley California. I was a student at Zen Center from 1970 to 1976 and lived at Tassajara for a while. During the last year of Suzuki Roshi's life I had heard his many lectures and sat a number of sessions with him—another of the great and miraculous blessings in my life.) When we got to the hot springs, I explained that there was a men's side and a women's side and that clothing was optional. Neither brother-in-law had ever been naked in front of another man in their lives, but after a brief hesitation entered into the spirit of the place and enjoyed the waters.

The last time I saw him he had already had his first heart attack and his hair was pure silver. Of practice he always said, "The more you polish a thing, the more it shines." In that last meeting he himself was a gentle penetrating source of light and love. Of his final performance, Pandit Swapan Chaudhuri, recounts that something was wrong. He looked over and Mr. Banerjee was red in the face. He had broken his Kharaj (bass) string, something that never happens, and was struggling to get a note out. Swapan-da stopped the concert. Pandit Nikhil Ranjan Bannerjee died the next day. (His name meant, ‘One who gives pleasure to the universe.') That he did.

Zakir Hussain, master of the tablas

I have played one instrument or another since I was big enough to hold one. I have studied the following in this order: Trumpet, Banjo, Sitar, Guitar, Piano. I spent about thirty years learning tablas from the incomparable Zakir Hussain, whose love and generosity are truly humbling, and to whom I am forever indebted. I began Banjo again in earnest at age 60 because I was missing melody. I had been listening to a lot of Bela Fleck and Allison Krauss. I was doing serious banjo practice when the base of my left thumb announced that it did not want to cooperate with my hellish practice regimen any more and promptly resigned in a fit of arthritis. What to do? At the age of 67 I began taking voice lessons from my wife, an acclaimed jazz vocalist and from a highly talented North Indian Vocalist Jayanti Sahasrabuddhe, the daughter-in-law of the great Veena Sahasrabuddhe. I am happy that each time I practice I'm a little more in tune. Now ain't that sumpthin'?

Footnotes

Ustad Allauddin Khan

Annapurna Devi performing in Maihar, India

*Annapurna Devi was the daughter of Allaudin Khan the most celebrated teacher of Classical Indian music of the 20th century. She, her brother Ali Akbar Khan, Ravi Shankar, and Nikhil Banerjee were all taught together by the master in his retreat in Maihar, India. Nikhil Banerjee once told me that because they were required to practice twelve hours a day; they would take a rest whenever they thought Allaudin wouldn't notice. One time, he came into the classroom and found them lying down. He said, "OK, you can lie down, but keep practicing." Later, in a story recounted by Steven Baigel in his film about Nikhil Banerjee, THAT WHICH COLORS THE MIND - A documentary on the classical Indian sitarist Pandit Nikhil Banerjee (a sample of that film can be seen here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b-J1DF5bsXs), when Annapurna Devi was betrothed to Ravi Shankar, the couple came to Allaudin Khan and requested that he grant a wedding wish, and that he must agree before they told him what it was. He agreed, saying, "How can I refuse." They then requested that he stop teaching Nikhil Banerjee. Ravi Shankar must have felt that the young Bengali's progress threatened his own career, though given his success, one has to wonder why this would have been the case. It was said that Allaudin taught each of his pupils differently according to their strengths and proclivities. Anyone who listens to Nikhil Banerjee will note how thoroughly unique and how different his style of playing is from Ravi Shankar's though they studied from the same master. The story continues with Allaudin Khan teaching the lessons intended for Nikhil Banerjee to Ali Akbar Khan who then taught them directly to him. Mr. Banerjee was instructed to leave his door open so that Allaudin could assess his practice and send corrections via Ali Akbar Khan in return.

Baba Allauddin Khan`s other disciples include Pandit Tmir Baran, Maharaja of Maihar Brijnath Singh, Pandit Pannalal Ghosh, Smt. Sharan Rani, Jyotin Bhattacharya, Indranil Bhattacharya, Ustad Bahadur Khan (nephew) and his grand children - Aashish Khan, Shubho Shankar, Dhyanesh Khan, Ameena Perera, Pranesh Khan, and Amaresh Khan (and countless others). As a principle, he never accepted cash or gifts from his disciples. As a matter of fact, he took care of the food and lodging expenses of his disciples. (http://www.itcsra.org/tribute.asp?id=27)

**The famed bansuri (bamboo flute) master Hariprasad Chaurasia.

***Shubhendra Shankar, son of Ravi Shankar and Annapurna Devi

[All photographs courtesy of Joe Cohen]