Muddy Waters was born on April 4, 1913 and died on April 30, 1983. The 35th anniversary of his passing has recently come and gone. For this occasion, I find no better reason to introduce to you a dissection of one of the greatest blues albums ever recorded, entitled Folk Singer. Before we begin, please allow me a bit of a pre-entry disclaimer: This article might be a bit different than anything you may have read before on this subject, so just indulge for a while, if you please. At certain points during the journey things might not feel like a simple critique, or typical record review—I readily confess to including several digressions along the way to cut a much wider collective swath. Biographical info, backstory material, linguistic forays, historical comparisons, theoretical constructs, contextual insights, and even a few onomatopoeian overtures—it's all gonna be stewing in this pot of blues. Hopefully it comes together for an audio-linguistic joyride. For lack of a better term, I'm calling it a forensic approach to Muddy's music. Are you ready? Ok, let's do this!

Folk Singer: A Forensic Approach

The fifties will always have the bragging rights of being the "golden era" of rock n' roll. But the sixties? Not so much. During the first half, Jerry Lee's great balls of fire had already burned, The King's hound dogs had howled, Johnny had been good (but Chuck the Duck Walker was caught being bad). Yes, Chubby Checker had twisted his way over Fats Domino's blueberry hill, but American teens hadn't yet started to twist and shout, had they?

In a gritty neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago sat a small legendary studio that ultimately became a powerhouse as the years went passing by. Chess Records was owned and operated by Phil and Leonard Chess, who bought the building and hired a few key people to run the recording studio and its offices. They also hired some of the greatest blues musicians in the world to make the music. Among them were three kings: Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon, and Buddy Guy. In this early part of 1963, these three gentlemen, along with Chess session drummer Clifton James (the originator of the Bo Diddley drum beat, did you know?) came together to do a special recording for the Chess label. It would be captured in a different manner than the usual approach, and there were reasons for it to be done this way.

By now, the once-plentiful and thriving urban Chicago blues scene was slowly dying on the vine in the black community; several live venues were losing steam and money too; even Muddy's main sidekick, guitarist Jimmy Rogers, had thrown in the towel as early as 1960 and said "I'm retired." His departure from the Chicago clubs lasted throughout the decade, 'til the next one started.

Some of Muddy's biggest Chess pieces had been already recorded between 1950-1960. But things had changed by 1963 when Waters, Dixon, Guy, and James came together for this seminal event, which took place shortly before the 1963 American Folk Blues Festival, an event which, in hindsight, may have very well been the impetus for bringing this session to fruition. Indeed, Muddy Waters was scheduled to perform as one of the main acts on the star-studded blues extravaganza. Based on well-documented itinerary notes from music historian Stefan Wirz, Muddy most likely made his overseas departure in the last week of September to arrive in time for the beginning of the Blues Festival tour in Frankfurt, Germany on September 24th.

Chess producer Ralph Bass, who wrote liner notes for the music that would become Folk Singer, mentions that the folk craze was taking over the country. He wasn't exaggerating—during this early part of decade in American music, it was all about the emergence of artists like Pete Seeger, The Kingston Trio, Odetta, Joan Baez, Peter, Paul & Mary, and a young Bob Dylan among others. But then it became more real when a few music researchers (Dick Waterman, Phil Spero and Nick Perls) went south and found the originators of Mississippi Delta music who were still alive and well, gradually coaxing them out of the shadows and back into the light. Son House, Sleepy John Estes, Skip James, Mississippi Fred McDowell, and some others were now suddenly all the rage, as if being raised from the dead—only they weren't dead, hadn't died. But now white college kids were rediscovering black artists—the originators of the art form—who fueled the folk blues revival across the country…

The Chess Brothers wanted part of that action. Certainly, their franchise was trying to capitalize on the folk movement. What they didn't seem to realize was that they had it all along. Hell, Big Bill Broonzy—the epitome of rural southern black folk music—had lived right there in Chicago, and it was no secret that he was one of the two biggest influences on Muddy's early evolution (the other being Son House). Truth of the matter is, all the best Chess stuff was already folk blues—'The REAL Folk Blues,' as Phil & Leonard eventually began labeling some of these LPs they released on Muddy, Howlin' Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson and John Lee Hooker. Muddy's Folk Singer project was the first of them.

What makes Muddy's Folk Singer so special to me personally? Well, for one thing, it's an album my father owned pretty much from the time it was released. I remember listening to it throughput my entire childhood, even after we moved from 2713 W. Jackson Boulevard over to the further South West Side of town. I heard this album so many times I actually can still recall where every scratch, crackle and pop on the vinyl was, and knew exactly when the skips would occur and when my dad had to get up and push the needle over the groove just to keep the album playing! But that was so long ago; still, I wondered: Was that record really as good as I remember—or was my fond memory of it just a sentimental journey? I decided it was probably time to take a closer look.

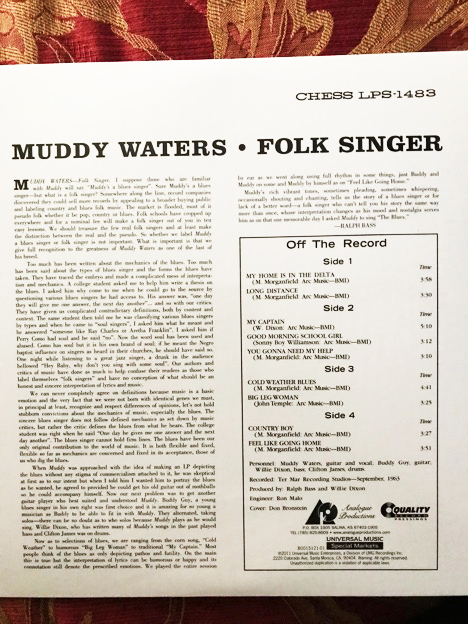

So…about a month ago, I talked with Chad Kassem, owner of Analogue Productions in Salina, Kansas, and asked him to send a copy of his company's exquisite pressing of Folk Singer. The music was originally re-released on vinyl by Geffen Records in 2015. By now it's well-known that Chad's vinyl issue of this highly-regarded album is unmatched. Here, then, are the basic facts of the Quality Record Press release:

Label: Analogue Productions – APB 1483-45, Chess – LPS-1483. Format: Vinyl, LP, Album, Reissue, Stereo, 200 Gram

Available at Acoustic Sounds, $55.00; 33.3 RPM version also available, $35.00; SACD version is $35.00.

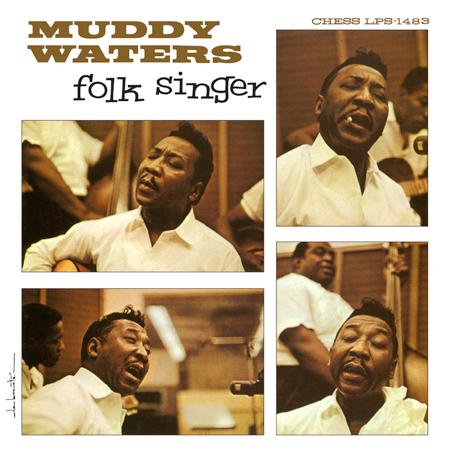

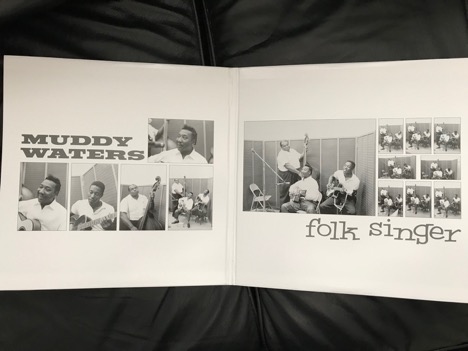

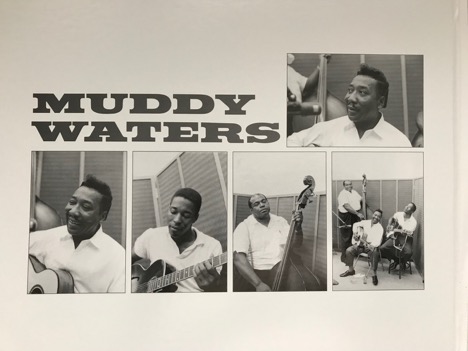

The photos were taken by none other than the legendary Jim Marshall. [By the way, did you happen to notice they're all dressed in pressed white shirts? Even casually they look clean and ready for business.]

Kassem really delivered the goods when it came to the care and preparation of this blues album that I have known and loved all my life. The music was culled from the original 1964 Chess analog masters, then plated and pressed at Quality Record Pressings on 200-gram vinyl. Equally as impressive as the music itself is the physical layout and overall packaging of the Analogue Productions albums, which is presented not in its original two-sided, single-disc cover, but in a 'first-time-ever' two-album gatefold jacket with extra never-seen-before photos in addition to the original cover shot.

Inside are two heavy double-disc, 45 RPM pressings (only 2 or 3 songs per side for deeper groove space). The two discs were cut at 45 RPM for the first time ever, and mastered by none other than the legendary Bernie Grundman. And to top it all off, there is the easy tear-away perforated plastic strip at the top of the plastic sealing; the special cardboard coating and cut to slide disc in and out easier; and the anti-static, non-scratching plastic sleeves to house the vinyl.

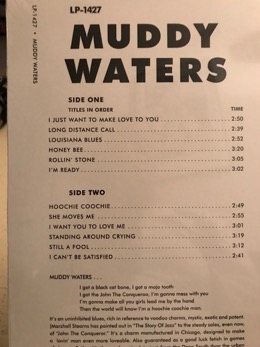

The original track listing of this 1964 Chess release looked like this:

SIDE A:

"My Home Is in the Delta" (Waters) – 3:58

"Long Distance" (Waters) – 3:30

"My Captain" (Willie Dixon) – 5:10

"Good Morning Little Schoolgirl" (Sonny Boy Williamson) – 3:12

"You Gonna Need My Help" (Waters) – 3:09

SIDE B:

"Cold Weather Blues" (Waters) – 4:40

"Big Leg Woman" (John Temple) – 3:25

"Country Boy" (Waters) – 3:26

"Feel Like Going Home" (Waters) – 3:52

The current Analogue Productions 45 RPM 200 gram reissue looks like this:

SIDE 1:

"My Home Is in the Delta" (Waters) – 3:58

"Long Distance" (Waters) – 3:30

SIDE 2

"My Captain" (Willie Dixon) – 5:10

"Good Morning Little Schoolgirl" (Sonny Boy Williamson) – 3:12

"You Gonna Need My Help" (Waters) – 3:10

SIDE 3:

"Cold Weather Blues" (Waters) – 4:41

"Big Leg Woman" (John Temple) – 3:25

SIDE 4:

"Country Boy" (Waters) – 3:27

"Feel Like Going Home" (Waters) – 3:51

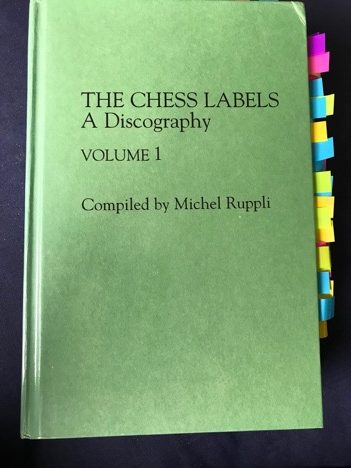

The length of the album clocks in at just over forty minutes. This was Muddy's only all-acoustic album, and it eventually was hailed in Rolling Stone magazine in 2003 as position #280 of 500 of the greatest albums of all time—which is quite an honor. It is important to note that when this session went down, it was done basically in one steady uninterrupted sitting, and each tune was done in one take. There is ample evidence to support this—from the reference book I bought back in 2010 when I was doing research on guitarist Jimmy Rogers, I tagged the page with the track list on Muddy's September 1963 session logs for Folk Singer [the takes are coded as numbers 12838 through 12846, which indicates that the tunes were performed in one take each, and in an unbroken sequence].

Notice that the specific date of the album is unrevealed – still not known to this day.

Before we dive into the music, let me say that this album is really interesting because, upon closer inspection, it is laced with just a bit of unexpected irony: the initial purpose was to capture the folk music roots and true deep-southern sound—except that when you consider the modern guitar playing of Buddy Guy and combine it with the incredibly high fidelity of the microphone used and strategic positioning and sonic depth of the EV 666 microphones the studio used at the time, the sonic clarity actually defies the rustic perception of that vintage, 'little log cabin made of earth and wood' soundscape that everyone might expect to hear. The lyrics and subject matter, however, still do justice to conjuring up those rural images in that regard. And there's so much more to love—Muddy's shiver-and-quake delivery on vocals and slide guitar—you can hear his slide literally battering against the fretboard—has stunning clarity when you're listening to this superior Analogue Productions release. Throughout the entire album, Muddy dips in range and dynamics so low you can't get under it, and then swoops so high and strong you just can't get over it—how good it sounds, I mean.

So the only thing left for me to do was to fly to Chicago and see the historic monument for myself—I needed to stand in the space where this legendary album took place. I placed a call to the Blues Heaven Foundation, which is located inside the former Chess building, and made arrangements with the manager, Janine Judge, who was extremely helpful to me the entire time from start to finish. Here she is sitting in the office of Phil Chess—and Leonard's room was just across the hall.

Ok, enough delay—let's head inside the studio and poke around.

About the studio: A brief history

The Chess recording studio where the music took place was in a 37x20 foot room, with a 13-foot-high ceiling. When I entered it, you wouldn't believe what I saw—a huge, three-paneled photo of the very session I was writing about—I took this as a great sign of things to come!

Janine let me inside the recording booth and I imagined what it must have been like when Ron Malo recorded Muddy's session. This view is me on the inside looking out onto the studio floor where the band would have stood:

Jack "Sheldon" Wiener (born in on July 2, 1935 in Chicago) was the brains behind not only the architecture, but also the sound. Wiener used to work for Milton T. (Bill) Putnam, the founder Universal Recording Corp. (since 1946) when it was located on 111 E. Ontario Street in June, 1953. Jack's primary job was "mastering," one of the most crucial and final phases in record process…doing this right is what made the records sound great. Since Chess was one of Putnam's clients, Jack worked during the night shift mastering the Chess Records urban music, or "race records" as they were called then.

At the time, Chess was located at 4750 S. Cottage Grove Avenue. But Leonard and Phil were looking to expand and improve in both size and sound. Instead of outsourcing to Universal as they had been doing, they now wanted to have in-house services of their own, and wanted their own mastering facilities. Jack's mentor Bill Putnam had already been lured away to work in Hollywood, California, for Master Recorders in 1957, so Wiener was now the man the Chess Corporation targeted. When they moved into the new location at 2120 S. Michigan, the two-story building was spacious, but needed lots of interior renovation to achieve their dreams. Most people nowadays know the history of the two Chess Bros. being the owners, but few people are aware that Leonard and Phil actually offered Wiener an opportunity to be a third-party owner/partnership of the building to help pay for the interior renovation of the studio. In return, he was given permission to operate his recording/mastering services independently upstairs on the second floor, which was why, if you entered from the back of the building, you would have seen his company logo on the door, which led to a separate stairway that led to the main recording room.

Jack Wiener went to work and slowly gutted the interior on the first floor to build what was, at the time, a "state-of-the-art" recording facility that housed the main recording room, the elevated control room, and a separate "audition room," which was a smaller recording booth on the other side of the hall. He also designed an ingenious two-way staircase built behind the wall of the studio—one staircase that led directly from the backdoor up to the recording booth for the engineers and other personnel, while the other went in the opposite direction so that the musicians could discretely arrive and enter the studio. It's a unique and fantastic-looking set of stairs. This view is taken looking downward from the recording engineer-side room exit:

Jack also found a way to convert two empty rooms in the basement level into what is now famously know for creating the Chess "echo chamber" sound.

Wiener basically used the two adjacent, similar-dimensioned rooms by sitting a speaker at one end with a high-end microphone at the other (He did this in both rooms to create two matching echo chambers—a feature no other studio had at the time.) On recordings, it made the room sound much bigger than it actually was. Two tubes came up through the floor, with wires running through them that led down to the basement where recording machines were held at the end of a long corridor. Here is a picture of it, taken while I was standing in the engineering booth where the pipes are located on the back wall:

When interviewed for the Open Vault radio show on WGBH, Phil Chess roughly described the reverb system this way: "We put out the first echo chamber… we did two different things: one—we had a mike in the bathroom with an amplifier and when the mike amplifier would feed it out, the mike would pick it up and delay was your echo till somebody went in the bathroom and flushed the toilets and then we were, we were out of luck. So then we got a sewer pipe and we did the same thing, we put a mike on one end of the sewer pipe and amplifier on the other and that's how we got our delay, where we got the echo."

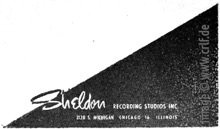

They used this on many, many Chess sides, including sessions for Bo Diddley, Howlin Wolf, Chuck Berry, Sonny Boy Williamson II, and even the Rolling Stones, who came by to visit during their first U.S tour in '64 and record several tracks for an album entitled 12 x 5—with Mick Jagger doing his best Little Walter impression on harp and Keith Richards doing his best imitation of Chuck Berry on guitar as they tried to capture the magic that the studio held. Here is the band (Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Bill Wyman, Charlie Watts, and Brian Jones) working on the tunes at Chess, including one they called "2120 South Michigan Avenue."

Other Company Men

I noticed on the back of the Analogue Productions album jacket that it says the music was recorded at Ter-Mar Recording Studios. The name change occurred sometime in 1963, and stood as an abbreviation of the two sons of Phil and Leonard Chess (Terry and Marshall, respectively) since the studio was housed inside the Chess building. This album was recorded in September '63 and released in January '64. At that time, if you were interested in booking a session with at the Chess building, the ad in the paper would have looked like this:

In 1958, Chess had hired Malcolm Chisholm as their first sound engineer for this studio. Chisholm served this role for a couple of years, after which he was replaced in 1960 by Ron Malo, who spent a considerable amount of time trying to improve the sound capabilities.

Ralph Bass [actual name Ralph Basso, Jr., an Italian-American,] was 52 years old when he served as the producer of the Folk Singer session, and evidently doubled as liner note writer for this and probably several other Chess albums. Truth be told, Willie Dixon was the man who knew the music from a players' standpoint and probably had just as much if not more influence than anyone in the room—he obviously was well-respected by all involved. He was the floor general, and all the musicians acknowledged his experience and authority on the recording room floor—much more than they did Leonard Chess, who often threw his weight around in ways that, more times than not, only served to aggravate the primary artists and sidemen. Willie Dixon was, by all accounts, a mediator, moderator, spokesman, and facilitator of practically every aspect of the recording process—composing, arranging, producing, performing, and directing the sessions. It is without question that he was absolutely essential to the success of this particular session—Muddy Waters relied on him for many things. In Spinning Blues Into Gold, Nadine Cohodas wrote that everybody got paid the same—$112 for the sessions according to union rules, except that Dixon, as the leader, got paid double.

The Players

The drummer for this session, Clifton James was approaching the age of 27 at the time of this recording. Born on October 2, 1936 in Chicago, Illinois, he had played or recorded with several other Chess men, including Muddy Waters, Sonny Boy Williamson, Howlin' Wolf Buddy Guy, Koko Taylor, Bo Diddley, and, of course, Muddy and Dixon. Not many people know him as well as they do Muddy or Buddy, so here's a photo of him.

From Lettsworth, Louisiana, George 'Buddy' Guy was just coming into his own. Born on July 30, 1936, he'd recently turned age 27 at the time of this recording, born three months earlier than James. Buddy had already achieved some success with a pair of singles that had been released on Chess, but his first LP for the label wouldn't come out for another 7 years. Still, he consistently made a major splash with his kinetic, frenetic delivery of slashing guitar lines—like he did at the Copa Cabana gig that had occurred a month before. Muddy decided then that Buddy would be a good sideman, and since he was also from the south, he knew all about Delta back porch blues anyway.

There is an often-told story that describes how it was that Buddy was chosen for this recording session—he was not Leonard's first choice. When he arrived in Chicago from Louisiana in 1958, Buddy met Muddy Waters immediately and was taken under his wing. Buddy's first Chess session was on March 2, 1960, when he recorded "First Time I Met The Blues." During that period, he was singing and playing with the heaviest stylistic influence of B.B. King. By 1963 he still was under that influence, which is why the Chess Brothers hadn't even considered him for a sensitive acoustic project like this. As the often-told story goes, Leonard told Muddy to go down South and find an old veteran to bring back with him who knew how to play the authentic Delta-style guitar. As far as choices go, Buddy Guy was the furthest thing from their minds. Muddy just told them not to worry—he wouldn't have to get on train, and to go ahead and set up the session—he already knew who he wanted. When he walked in with Buddy, Leonard was incredulous—totally shocked. And he wondered what the hell Waters was doing bringing Buddy to the session, of all people?! But Waters was unmoved, and literally told them to "shut the f*ck up"—he knew exactly what he was doing, and Buddy would get the job done. Listening to the recording, you can tell Muddy did know what he was doing, and musically speaking, Buddy damn sure knew what he was doing – they sound perfect together, and work seamlessly like hand-in-glove. When Leonard finally asked Buddy 'Motherf**ker, how'd you know that?'" Guy basically responded, "How do you think I got I started? I learned first on an acoustic guitar—I knew this [style] before I learned anything else!"

Buddy was on this session by default—insisted upon by Muddy, who chose to ignore Leonard's underestimation of Buddy. Not only did Muddy know of Guy's capabilities, but Dixon knew it as well, stating in his autobiography quite clearly that "Buddy really was a better guitar player than most people estimated. A lot of people can play really fair guitar, but they don't have the ideas. Buddy could play anything Muddy could play, only better…he was better than all of the [others] at Chess…I don't know none that was better than Buddy at Chess."

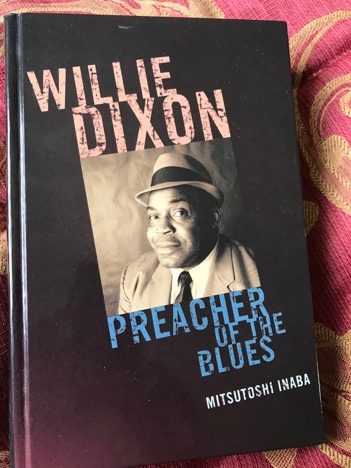

In fact, the person who was originally destined to sing the Dixon-penned song "The Same Thing" was Buddy Guy! Buddy and Dixon had rehearsed the tune together for 6-8 months before they went into the studio to cut the track. Leonard overheard the tune, placed a quick phone call to Muddy, and suddenly Waters appeared at the studio. Leonard insisted that the tune be taken from Buddy and given to Muddy. Buddy knew what happened, but was powerless to do anything about it. Leonard said, "This is a Muddy Waters tune." Muddy just looked at me and said, "Don't move, play, motherfucker." So I ended up playing guitar for Muddy Waters on "The Same Thing." I couldn't go against Muddy because I don't do that. I couldn't even get angry at Muddy." [Willie Dixon: Preacher of The Blues, Mitsutoshi Inaba, p. 239.]

The Instruments

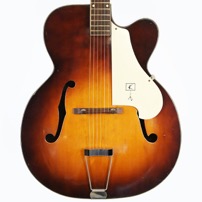

According to sources, at the time of the recording Buddy didn't own an acoustic guitar—a notion that is highly probable, since his reputation had been primarily built on his electric prowess. Supposedly, Muddy Waters lent him one of his archtops for the recording session. Although I cannot confirm that as a fact, I can confirm that the guitar in question is a Kay model K1 Jumbo archtop, circa 1955. When I looked this guitar up on a web search on Reverb.com, I found that this particular sunburst-finish guitar, made with laminated maple back and sides, sold originally for around $100 including a case. It featured a large 17" wide lower body, which is what gives it the sonorous appeal.

Then there are sources that erroneously report that the guitar Muddy has in the photo shoot is a 1959 Martin 00-18E acoustic/electric guitar for both 1964's Folk Singer, and at the 1960 Newport Folk Festival. This may be true, but the guitar on the cover of the Newport album is absolutely not the one used in the photo shoot for this Folk Singer album. [Personally, I say it actually looks a lot more like a Martin model 00-18G, and here's why: Note the smallish body size, and the slotted head stock. By the way, the G stands for "gut" a slang term for the type of nylon string used for classical guitars, which fits this description perfectly.]

According to the americanbluesscene.com website, the Martin 00-18E now resides at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Museum in Cleveland, Ohio. [See https://www.americanbluesscene.com/guitars-muddy-waters-play/.]

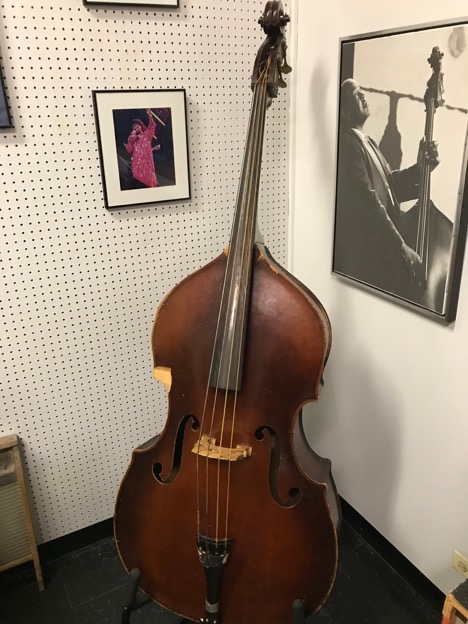

Meanwhile, Willie Dixon was playing this upright acoustic bass, which currently resides in the Blues Heaven Museum:

The Music

Ok, the moment you've been waiting for: let's dissect some blues! Let's go deep, deep into the woods of this earthy album, and crawl inside each tune, one at a time, and listen closely on 200 gram vinyl and a nice pair of speakers (or headphones)… Muddy is in the left channel, Buddy is panned right, while Dixon and James are straight down the middle.

SIDE 1, TRACK 1: MY HOME IS IN THE DELTA

We discover almost immediately that Muddy is an alchemist, bending words and tones to his will. Now, notice how he says 'delt oh ho!"…to set you up when the rhyme comes that only he knows is gonna be "and people I sho' do hate to go!" Isn't it ironic that he's talkin' about his home in the Delta and leaving Chicago?? It was from there he left to get away from the Delta!! But he's missin' his roots and won't be back no mo. His 'little girl' don't know what shape he's in—and boys, you know he ain't had no lovin' in God knows when. Hear him as he's scratchin' on those twangy strings while Buddy supplies great accompanying single string licks all along. Then Muddy launches into the patented solo—maybe the first time most of us had heard him do that on acoustic guitar in the studio…and let's talk about that for just a minute.

This is Muddy's standard, well-worn pattern of licks that comes as a surprise to no one, and is copied by everyone by now. It's so standard fare when playing a Muddy-style Chicago blues that it almost sounds ridiculous not to play it. How is this possible? Well, if you could have asked Muddy he would most likely would have told you something along the lines of, "There is nothing else you need to say once you get something that works." It's literally a note-for-note solo that he played for his entire career—and guess what? Everybody knew, and nobody cared. How cool is that?

It's a sign of greatness, an acknowledgment that his assessment of the situation was absolutely right—we can look for flashiness and extravagant high-flying daredevil licks from whomever, but, it's not what we came to expect or demand from Muddy. It's because he taught us first that it's not what he ever expected or wanted from himself—and that is a sign of great self-awareness. And you know who else developed that same sense of self-awareness over the years and pared his mastery of melodic expression down to its purest form? None other than B.B. King, and his loyal loving listeners applied these same rules to him: Do your thing, we all know and understand and embrace what that is. We don't need anything more from you.

SIDE 1, TRACK 2: LONG DISTANCE CALL

This tune opens with the exact same lick and in the same key and same tempo as the previous track – what does that tell you? What I just said—that this man knows exactly who he is, what he wants, and why he does what he does. He's creating a comfort zone for himself—recreating his Mississippi moods through his Mississippi grooves—where things are simple, straightforward, clean and clear—and most importantly, consistent. Why, you ask, is this so effective in the blues format? Because it puts the energy and emphasis on the more important aspect of the tune, which is the lyrics. Just as in the first tune, the intro here is merely a setup, an opening salvo to announce a passionate plea that is about to come forth.

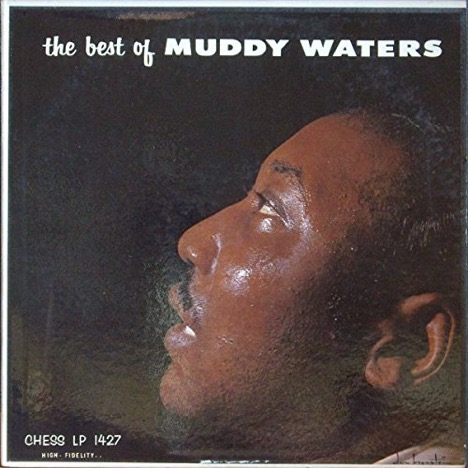

He's done this tune before, you know—it was on an album called The Best of Muddy Waters, the first full length LP released under his name, released in April 1958, a compilation of previous 78's he'd recorded for Chess from 1948-1954. But that earlier arrangement released in 1951 [#1452] of "Long Distance Call" with bassist Ernest "Big" Crawford and "Little" Walter didn't sound like this one.

That first version was in a different key (F), had a different tempo (faster), had a different instrumental configuration (amplified guitar, thumping bass from Crawford and Walter's wailing harp) and was sung with a different vocal timbre and attitude.

So the setup here is Muddy playing his opening line in the key of E in an open tuning, while Buddy plays the same lick two octaves lower in the open E blues pentatonic finger pattern that most blues guitarist are quite familiar with. [As a side note, I will tell you as matter of fact it is the first guitar lick my dad actually taught me to play, and used this very album as a listening example to show me where he got it from—literally a direct quote, musically speaking.]

All Clifton James is doing is gently thumping the kick drum and slapping the snare drum on beats 2 & 4, and it's a unique sound in this rural recreational setting – something that sounds as beautifully dry (with the Chess reverb adding some wetness) as a rolled up newspaper on the drum head. You can tell he's using stiff brushes – sticks would cut waaay to hard and brittle and ruin the moment…you can hear the wires that are fanned out to the right length to create a warm but crisp attack on the calf skin heads…also, notice there are no cymbals or toms or even a high-hat keeping 2-&-4 accents for the 4/4 tempo? You know why? 'Cuz they don't need it.

Notice the reverberation on the word "Plee-EEZE" call me on the phone some tiiime." Immediately After which, they instinctively switch registers simultaneously, and Muddy goes down two octaves to play quivering trills on the note E using his second finger on the 2nd fret of the D string, as Buddy then goes up in the 10-12 fret range Muddy just evacuated and plays blues pentatonic licks. Now observe how Muddy matches that low guitar trill with his vocal quiver when he says in a throaty tone, "Ahhh-ahhh—When I hear your voice… ee-ee-EEase my worried mind."

The down beat is delivered by Dixon's fat, punchy reverbed bass…on the first line of the second chorus, you can hear him calmly (eerily almost) tell his woman, "one of these days…I'm gone show u how nice a man [pronounced "mane"] can be…" and the groove settles just so…but then he comes around lively on the second delivery of his line "ONE of these dayyEEzzz.." and that's when you really hear hear the room's reverb really pop! And I just love the way he does not pronounce the hard 'C' at the end of the word "Cadillac' he actually says, "Ahmo buy ua brannew caddilaummmmm.." But we know exactly what the word was. And do you dig how cool the walking counter-melody is that's being supplied by Buddy as Muddy takes his shivering guitar solo? It sheer perfection, and all instinct. Yeah, these boys are swingin'.

The same approach happens when you hear him deliver the next verse, "hear my phone wrangin….sounds like a long distance call…" and immediately after those words, you hear—in response and in tandem to Muddy's patented one-finger trill on the second fret of the D string—Buddy's stark jab of a two-fingered double stop on the 7/8 frets of the B and E string. But even hipper than that, you hear a beautiful jazz-flavored descending walking bass line from Dixon, totally different from the 2/4 feel he's well established during the entire tune…until now! It's no coincidence—Dixon had already gained some serious jazz experience before he became a leader for Chess—in the late forties, he was in a popular jazz trio called the Big Three, with Leonard "Baby Doo" Caston on piano and Ollie Crawford on guitar—and Dixon played a mean standup bass.

Side 2, Track 1: "My Captain"

The echo chamber takes front and center stage on this piece. The thing about the reverb on this album is that there are degrees of it across the entire sonic spectrum—Muddy's voice, his guitar, the bass, Buddy's guitar, and even the drum, which is the driest one relatively speaking (and not performing on this track). The room is doing its work, and Muddy has calculated the distance between the mic and his mouth; the distance between the mic and the amp; the amp and the space and size of the room that creates the natural sustain and decay. This is not reverb added later—this is reverb captured there and then, using the tube/chamber technique I referred to earlier.

Did you notice the delicate dance that he and Buddy have on guitars, and the musical guitar-specific cues Muddy gives? The turnarounds are the street signs, always given in the same sounding corner but not always placed at the same location, because the corner moves, and Buddy has to wait for it. This is the true nature of the country boy Muddy sings about…Hopkins and Hooker and House all had that same thing. ("Oh, that saaaame thaang…" ) Wolf and King had it too. You can even hear Muddy snap his fingers at Buddy to get his attention to cue the exit ramp (the end of the phrase, "Oh yeah boys, with the seam behind,") that Buddy previously missed and Muddy takes an extra lap around lyrically to give him another chance to try to catch it.

There have been some misgivings about the lyric content of some of the songs Muddy sang on this album, and the one that is most egregious keeps getting copied and spread like a virus via the internet, appears numerous times on line—to the point where it is basically being accepted as gospel.

I couldn't understand the words from a few lines in the verses, so I called several blues people I knew to try to get the words right—first Scott Dirks, then Chicago blues legend Billy Flynn, then I called up the legendary blues guru Dick Shurman, who agreed with me that the lyrics weren't correct and didn't make sense, but also had a hard time trying to dissect the words and meaning. Then I went to as direct a source as I could—Larry "Mud" Morganfield himself, who told me he would listen to the song with close inspection to see if I was right in my idea of what I thought was correct—he called me back and said he agreed.

At last I finally called Jim O'Neal who wrote, among many legendary documents, the intro to the Mitsutoshi Inaba book. Jim also agreed about my notion of the words being wrong and he agreed with the storyline and added that on a prison chain gang—or maybe a crew of levee workers—the men typically referred to the boss as "captain." This comment somehow triggered a memory that I had forgotten about—a passage in Dixon's autobiography (p. 26) that told his own real life story of his suffering under just a mean captain referred to as "Crush," after he and his friends were captured in Clarksdale, after riding the rails with several other hobos. Dixon actually watched more than one person get beat to death by Captain Crush, and knew his turn would probably be coming up sooner than later. More than likely this is where the lyrics of "My Captain" came from—his personal experience and/or overhearing those words sung by other chain gang members.

Oh captain, captain, hmm, oh, my captain so mean

Oh captain, captain, hmm, oh, my captain so mean

Ah, he don't feed me nothing, oh yeah boy, but soya bean

The second verse is commonly published this way:

Oh, the cook's alright

Oh yeah, but the captain so mean

Hey, the cook's alright

Oh yeah boy, but the captain so mean, I mean so mean

Ah, he don't let me drive nothing, but this old beat-up wagon team, he don't let me drive nothing, but this old beat-up wagon team

He actually says "Ah, he don't let me drive nothin'…just a ol' beat up raggly [raggedy] team," raggly is a more common slang term used by Southern blacks.

Yey, I worked all night

Oh yeah boys, and I worked all day, ah, oh

So sad, so sad

Yey, I worked all night

Oh yeah boys, and I worked th' old bell

Ah, I couldn't find my mule

Oh yeah, fella'd show nowhere

Forgive me, but half of these suggested lyrics presented in this verse don't quite make sense. But once again, Jim O'Neal came to the rescue and pointed me toward a couple of specific passages found in a few sources that cleared things up. First, he mentioned one of the most thorough essays on mules and men in the South that I'd ever seen called "Mule, Get Up In The Alley: A Tribute To The Mule in The Blues" by Max Haymes. This is where I first discovered that the original phrase "Old Maud" was a term used by black men working in the train roundhouse to refer to a locomotive that was big, strong and indefatigable. It was quite common to refer to mules as having some of those same characteristics. So, at least now we have a much more logical account of what words Muddy is saying and why.

What's actually going on here is that Dixon has named the team of two female mules. And Muddy is working them both, to no avail. 'Maud' was a common name for blacks to name a mule since it was a popular comic strip written in the early 1900's by Frederick Burr Oper called "And Her Name Was Maud." [It was about a revenge-kicking mule.] With this understanding, the lyrics in the verse make more sense and fits the theme of every other verse in the song:

Ayyyy, I worked ol' Maud

Oh yeah boys and I worked ol' Belle

[aaahhh mmmm…So sad so sad]

Ayyy, I worked ol' Maud

Oh yeah boys and I worked ol' Belle

Ahhhh, I couldn't find a mule

Oh yeah fellas, with a shoulder well

Yey, my wheel mule is crippled, hum, you know, my lead mule is blind

Yey, my wheel mule is crippled, hum, yes boys, and my lead mule is blind

Now I ain't gonna buy my baby no more stockings

Oh yeah boys, with the seam behind, hmm

Fella I mean, with the seam behind

Hmm, people, with the seam behind

Some people even wrote, "seem behind."

My original theory on why this song had such mysterious lyrics was that it was probably taught from Dixon to Muddy right there on the spot, and written solely for the purposes of the recording session. But upon closer inspection, it's more likely that although Dixon suggested and re-worked the lyrics, Muddy would have been quite familiar with those original Fred McDowell verses since he was indeed even older than Dixon was (by two years and three months), played guitar, and was quite familiar with those Mississippi-born lyrics and commonly coined phrases contained therein.

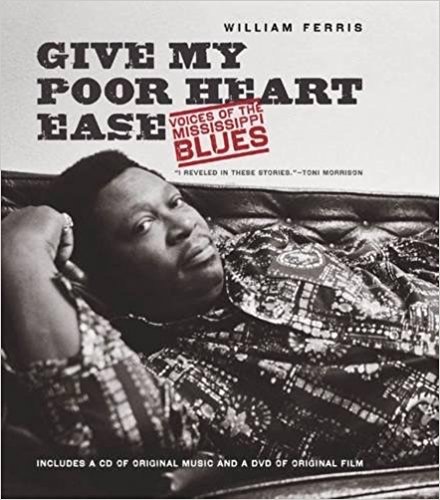

But then, O'Neal went even a step further and provided yet more insightful reference material that I hadn't had in my possession—a book that proved to be a great treasure trove for blues enthusiasts. Jim had been long time friends with Bill Ferris, the eminent folklorist and blues scholar who was the Director of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi, and is currently serving as senior associate director, Center for the Study of the American South at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. From a biographical interview in Bill Ferris's book, the Gravel Springs blues musician Otha Turner talks about always singing the lyrics to the song "Levee Camp Blues" recorded by Mississippi Fred McDowell:

Oh how can I drive it, how can I drive it,

Done broke my line.

My when mule crippled and my lead mule blind

Then we discover the real truth: Dixon co-opted much of the lyrics straight from that song:

Well, I worked on levee

Honey and I worked old Belle

Well, I worked old Lou Captain

Lordy and I worked old Belle

I couldn't find a mule

Lord with a shoulder well

And there it is, slightly altered for Muddy to sing:

Ayyy, I worked ol' Maud

Oh yeah boys and I worked ol' Belle

Ahhhh, I couldn't find a mule

Oh yeah fellas, with a shoulder well

The topic fits the mood and content of the entire album, which reflects the overall intent of the session itself—to show Muddy's relationship to his original southern roots—the folk life.

If you follow the lyrics carefully, slowly the picture becomes clearer, and the story emerges. The song starts out as a story about a "captain" of a prison chain gang who treats the prisoners mean and only feeds his workers soya (soy) beans, although Muddy doesn't blame the innocent cook who has the unenviable job of having to serve it to him every day. Muddy is mainly singing about a plantation owner who is barely feeding him enough food to eat for him to have enough strength to work the fields every day. This leads to the clearer understanding that Muddy is not singing about a "wagon" team (as stated in most of the often-copied erroneous printed lyrics found online), but a mule plowing team, one of which is crippled and the other that's blind. Both mules are weak and barely have the strength to work, but Muddy works them hard anyway—the whole time wishing he could find just one mule that could do better than either of the two. And finally things don't "seem behind" for him—he's complaining that these mules won't work hard enough for him to earn enough sharecropping pennies to buy his girlfriend the preferred stylish stockings with the nice little seams behind the leg. It's classic Willie Dixon lyric writing.

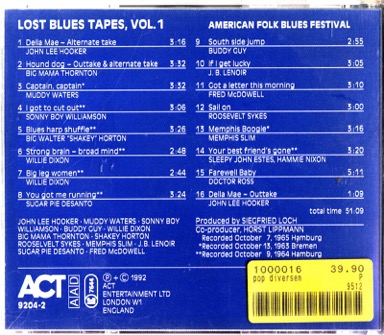

By the way, you won't find any previous version of this song anywhere in the Chess catalog, nor will you find it recorded again after this session—it was a singular affair, with Muddy and Dixon's version most likely on that day at the studio. But wait, there's a twist in this story: Act Music +Vison label released a 2-disc CD set in 1992 called LOST BLUES TAPES VOL. 1 1963-65 (produced by Siegfried Loch, and co-produced by Horst Lippman). This disc has a live performance version of what was labeled as "Captain, Captain"—notice its listing on track 3, recorded first in Bremen, Germany on October 13, 1963 [3:32 in length];

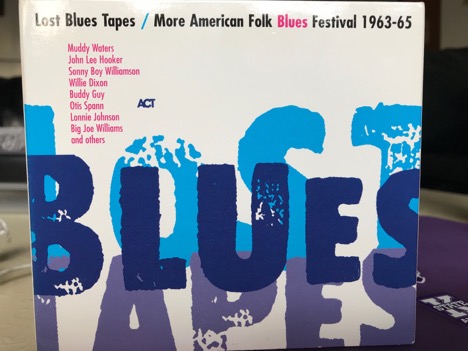

There also is a more thorough vinyl release of this same material (plus more of it), entitled Lost Blues Tapes / More American Folk Blues Festival 1963-65:

Disc 1 has a Bremen, Germany performance on October 13, 1963 (length is 3:45), and Disc 2 version is a different performance of the tune in Hamburg, Germany on October 9 (length is 3:32). This means that these were extremely rare (maybe only!) publicly documented recordings of that tune, as they went on this overseas tour performing this tune for the first time since the original September '63 studio session, although the album's version was yet to be released—Chess most likely didn't have enough time between the completion of the recording and the announcement of the European tour as it was mentioned in the June, 1963 issue of Blues Unlimited. Regarding the entire notion of the nature of the album project, Jim O'Neal offered the following insight, saying "it seems that Chess was probably capitalizing both on the folk music boom in the US and the AFBF in Europe." All the evidence does appear to support that statement. It is interesting to note that on these versions, Muddy sings an alternate set of lyrics to the ones he'd recorded a month months earlier:

Captain captain, what make u treat me so mean

Captain captain, what make u treat me so mean

Now u know I, asked u for water… and you brought me gasoline.

Side 2 Track 2: "Good Morning Little School Girl"

Muddy reworks the 'original' Sonny Boy Williamson I tune. Dixon's bass is panned left, playing in a gentle two-step (counted as in 2/4, or "cut time," meaning you have fewer beats to have to count, and it feels this way: "one, two; one, two") or can be counted as a fast 4/4 time i.e. "1-2-3-4, 1-2-3-4"), obviously more numbers involved, but it takes the same amount of time and covers the same amount of ground, so to speak—it like taking four quick short steps as opposed to only two longer strides at half the pace, with each being twice as long. James is slapping on beats two and four, also panned left buddy opens with the clean bright treble tone of his steel string acoustic, his guitar panned in the right channel, Muddy's voice and soft guitar almost inaudibly trilling low E note underneath.

Now, most blues forms are cycled in even number of measures, based on a European system of 12-bars, each bar with 4 beats per measure. Notice that if you total up the measures, this particular form adds up an odd numbered 19 measures. The chords follow the typical I-IV-V [Roman numerals are typically used to identify diatonic positions in the major scale instead of 1, 4, and 5] blues chord progression, using three chords. Since this tune is in the key of E, the chords are E7, A7, and B7—all three chords are dominant sevenths—typical of the blues progression.

What is not typical, however, is the length of the phrases when added together in "School Girl." The three words "Good Morning Little…" is the antecedent phrase that leads into beat 1 and as of the words to the verse "School girl," the phrase lasts 4 measures, then the IV chord (which is an A dominant 7th) lasts for three measures, then the E7 chord for 4 measures. The word "mother" starts the next two bars in B7, A7 for two more, then the last four are back on the E7.

For his solo, Buddy starts his entire phrase one measure late in the cycle, but then after the four measure phrase, he delays the next three–measure phrase by four beats, thus adding yet another measure to the length (which means he's now two measure behind)…but what happens immediately after that is quite amazing—Dixon literally turns his beat around in mid-air, deliberately drops a beat and puts shifts his entire beat over by one quick tick. Upon the words "With you," they are back on track. Muddy is just chopping wood, keeping time with James, who never stops slapping two and four on the snare, and they all line up together, as if nothing ever happened, and complete the blues cycle through the V-IV-I turnaround as smooth as glass. So if you're counting, Buddy's solo stretches a 19-bar form into a twenty-measure solo, with an extra two beats (half measure) added between measure 5 and 6. (I challenge any blues band to play that phrase exactly as these guys did it.)

The thing is, it sounds absolutely organic to the music, and the band is just chugging along naturally as if they never felt a bump in the road. It's like a cat that misses a jump but lands on its feet any way and struts away coolly as if what happened had been planned all along.

You have to appreciate the fact that these are not schooled musicians in the traditional, academic sense; they don't read music or analyze it the way "scholars" do, but they are smarter in an instinctual way than could ever be taught in any ivory tower—kinda like the way blind people can't "see" but they hear better than most people, and they seem to know exactly where they are and there are acutely aware of their surroundings.

Notice how he says, "I'm gonna by me a air plan," also when Buddy takes his last melody, Willie goes into a straight 4/4 walking bass line for exactly one single measure, then immediately back to a 2/4 feel. It's like watching someone turn a corner and just break out into a little hop skip and jump, then start walking normally again.

Side 2 Track 3: "You Gonna Need My Help"

Notice how well Muddy accompanies Buddy's solo with a perfectly articulate chord progression. If you listen very closely, you can hear Muddy play the third, then the flat third to indicate the IV chord.

Muddy applies the same kind of walking accompany line that Buddy gave him in the previous tune. Also, instead of playing the V chord, Muddy does something that even many guitar players don't realize—they go to the ii—(note F#) instead of the typical, expected note B, or the V. Then Dixon does a descending four-note bass line on the last verse (E-D-C#-B) – he plays the second fret E on the D string, hits the open D, then notes C# and B on the A string—the C# actually indicates a Mixolydian scale which is appropriate for the dominant chord that Buddy is playing and the melody Muddy is singing.

You can hear Buddy playing his three favorite pet phrases repeatedly underneath Muddy's countermelody—he knows exactly where to put them, and how not to over-play them underneath Muddy's role.

Side 3 Track 1: "Cold Weather Blues"

This one doesn't need Clifton James' drum 2/4 pats or even Dixon's bouncy bass…because it floats ethereally in its own air space and time, Muddy repeats his last line and takes his time doing it—this is one that is almost impossible to count in even 4/4/ beats or measures. This is beautiful dance just between Buddy and Muddy. It's when you hear the solo that you realize just how well they use silence and space as a musical tool. You can just barely hear Muddy keeping time tapping his foot on the floor. The very first note is them playing the same note—E, the home key, and they meet up again perfectly at the corner on the B, the V chord.

Lyrically, he's asking for his woman, who is so damn cold she won't even respond. Hot springs water doesn't even help her none. If times done get no better, he's gotta head back to Mississippi "where the weather suits my clothes."

It's so cold up here in the north that even the birds "can't hardly fly," just go back down south and let this winter pass on by—he says the line four times. After the third one you can literally hear him snap his fingers to get Buddy's attention, to signal that this next one is the last one—we headin' out now.

Side 3 Track 2: "Big Leg Woman"

Still not using Dixon and James on this tune, and the tune only has three verses. This song has a slightly quicker pace—more like mid-tempo stroll. Muddy sends a warning to ladies, "Big leg womens, keep yo' dresses down," "If you roll yo' belly like you roll yo' dough, people just cryin' for mo.'" I love the elegant simplicity of buddy's solo—he's not flailin'—he plays the statement four-note phrase four times in a row with no elaboration on them whatsoever—it's a perfect example of less is more, and his mastery of restraint is impeccable. Also notice how on the main verses one guitar "chops wood" on four beats slightly indicating the flavor of the chord, which indicates that keeping that time steady is more important than the chord itself. And even in Buddy's solo, he chops wood for himself in between the four-note phrases, and goes right back to choppin' wood immediately after, as Muddy sings his last verse. Also notice that in the turnaround, Muddy and Buddy play almost exactly the same 2-measure phrase getting back to the last verse—you can hear the direct influence the Mississippi approach to playing blues, Muddy had on Buddy, and also how well Buddy learned it.

Side 4 Track 1: "Country Boy"

Willie Dixon is a bit out of tune with the guitars (his low E string is just a hair flat), most likely because he laid it down for the previous two tunes. The reverb really jumps out at you on the first word "Don't" in each verse of Muddy's vocals. Buddy plays the repeated loping counter-melody. Muddy shimmers and shakes on his one stinging note in between lyrics. When he solos, you can really hear how fast his left hand is vibrating, especially when he hits the F# high on the 14th fret when they get to the V chord, and you hear that clack-clack-clack-clack against the back of the guitar neck. It sounds sooo sweet. It's a simple, straight-forward tune and is over in fairly short order.

Side 4 Track 2: "Feel Like Goin Home"

They literally saved the best for last. It's almost like Muddy said to them, "Alright, everybody: clear the room—I'm about to bring it all back home." All the way back to April 1948 when he first recorded this for pre-Chess era Aristocrat label (1305), achieving his first breakthrough hits. Muddy starts this tune alone, sliding in open G tuning with the capo on 3rd fret. Starts with an entire chorus solo as an intro. Shimmering, shakin'. His voice right from the start, opening word, the way he says, "wellll, gettin'..." You just know there's a story he's about to tell. And surely he does. This man says he "feel like blowin' mah hone" but he woke up and "all I had was gone." Subtle things like if he enunciated "correctly" as 'horn,' it ruins it completely, no? I mean, seriously—that doesn't nearly have the same ring or effect as 'hone' which flows so much better with 'gone,' do you not agree? This is deliberate slang worked to seamless effect to not only create unison in rhyme but effortlessly maintains the original intent and keeps the inference intact (and if you don't know what this double entendre means by now, I can't help you here and now—we'll talk later).

"Late over in the even'n', chile…." There are all these subtle things that he does scattered throughout the piece that lets you know he is seriously feeling this tune, let me list them piece de resistance.

Brooks runninto the ocean, boys…[haha] and the ocean—nowlookhere—runnin TO the sea…" the whole time you can hear that thud of his foot pumpin' perfectly in time, while he singing the lyrics and playing descending countermelody. He also inserts other sly gems scattered throughout the piece: "Well alright!" before the first melodic solo lick, band, and "yayyyy" right after.

"Minutes seem like hours, and hours begin to seem like days." Indeed, Muddy's agony stands still, frozen forever, and yet time seems like it lasts, stretches for mile and miles, beyond forever. It's absolutely exhausting to even think about, let alone feel, and he just wishes she…"hoo-hoo well boys!" would stop her low down ways.

This is the strongest tune ever, and it's amazing that he seemed to have saved the best for last. It's a rare thing to hear someone in the studio releasing that kind of power —most recordings capture the artist fully aware of their surroundings. What you're hearing now is a rare thing—Muddy forgetting himself and going inside himself—he's left us for a minute, and he's gone, we hear what's left of him after the fact, but, at that moment, he's a ghost. What you also hear is him having the greatest time being gone—outer-body experience. You can hear him smiling, grimacing, mouth twisting, shaking his head, chin, lips, mouth, throat tremors, that's how he gets the syllables, tones, curled vowels, unending unearthly and unfamiliar trails of melismas attached to the end of familiar words. And blurred lines between the ends of sounds and the beginning of the next one, like how he says, 'brooksrunnintod'ocean,d'ocean runnin'…into the seaaaaaah...'

In the best of the best, there's a certain level of confidence combined with audacity in high art that is extremely rare, and you can find it just about anywhere in if your eye/ear/nose/tongue is keen enough to pick it out. Think Marlon Brando in movies. Think Gianni Versace in fashion. Think Frank Gehry in architecture. Think Daniel Bolud in gastronomy. Think Miles Davis in jazz. And on and on…

The thing about it is, when people are doing it at that level, they ain't askin.' When you run up on people like that, you just gotta deal with it for a minute…If you wanna know how they got that way, you have to go all the way back to the beginning—even before their beginning—cuz it's that deep. These are inherited traits that were honed over time, and it's the difference between them and the rest of us. Yes, Muddy Waters had that.

If you saw and heard him do it at a concert with a lone spotlight on him and a Panavision camera slowly wheeling around him as the cigarette smoke created a blue haze against the moon-yellow beam hanging overhead aimed squarely on him against the stark-naked dark, you would still be drooling; drooling over the very same moment where most academy-award-winning performances are captured by screen actors, and cinematographers—and sound editors—are deified, and directors are worshiped as gods and live forever. This is nothing less than sonic cinematography I'm talkin' here. The entire album sounds like the movie it looks like; and it looks like you can smell the fresh air, and touch the warm southern soil he's trying to return to, and can taste the bitter cold in the north from which he's desperately trying to escape. This is what those well-placed microphones, and well-tempered echo chambers accentuate when a truly raw performance gets captured.

And that's what's so great about this album. The world is a better place for it, and Chad Kassem made a smart move when he went through all the trouble of serving up this two-disc platter in its finest edition yet—it was well worth the trouble, and I'm one of many who feel that way about this Muddy Waters Folk Singer.

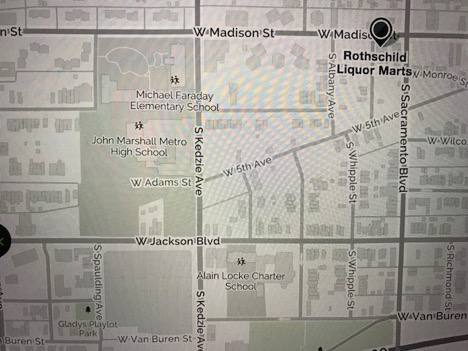

I mentioned earlier that the studio was located on the West Side. It was, coincidentally, not far at all from where I lived and where the blues artists roamed the streets. Yes, indeed—this writer was just two years old at the time the tracks for Folk Singer were being captured. But my dad—an amazing blues harp player himself—was actually hanging out with none other than Little Walter on a frequent basis. The two of them, as it turns out, were good drinking buddies who frequented the Rothschild's Liquor store located at 3015 W. Madison—and it's still there.

We lived only half a block away on 125. S. Whipple right off Madison Ave. My cousins, aunt and uncle (Louis Cobbs) lived across the street at 131 S. Whipple, right at the intersection where W. 5th Street cuts an upward diagonal line between north-south running parallel streets of Kedzie and Sacramento. (And, coincidentally, just a short block east of that liquor store on the southwest corner of Madison and Sacramento was the very popular blues club called Ma Bea's—above which legendary pianist Blind John Davis lived.)

My uncle—my father's youngest brother, remembers meeting Little Walter a few times but of course, never hanging out with him—he was only sixteen. But he and my other uncle John told me very clearly that my dad had Walter over all the time because dad, Little Walter and my uncle Louis hung out together and drank from bottles they'd procured at Rothschild's. My dad's older brother was also there. (Two years later we moved nearby to 2713 W. Jackson Blvd.)

I still relish the thought of being literally only minutes away from where the legendary artists who created all this great music took place on South Michigan Avenue. As fate would have it, not only did my dad hang out with Muddy's favorite harp player of all time in '64, but Muddy's son, Larry "Mud" Morganfield, was also living in the same area around the same time that my aunts, uncles and young cousins were growing up. The past has suddenly crossed paths with the present—and in a really cool way. I started this article on April 4—the birthday of Muddy Waters. I spoke to Larry on that very day, to let him know I was doing this article, to pay respects to him and his dad, and, as it turns out, "Mud" was familiar with my family and relatives from way back when we lived on that side of town—how cool is that? He knew my uncle Louis Cobbs, my cousins, and other mutual acquaintances. We had a wonderful warm conversation about his legendary father, and we had another follow-up call later in the month about some of the lyrics and meanings behind the words in this literally "once-in-a lifetime" Chess recording—it's the only time Muddy Waters recorded a totally acoustic album, which makes it extra special.

I find in the words of veteran guitar journalist Jas Obrecht quite an accurate summation of the man and the music he made: "Rolling his eyes toward heaven and shaking his head like a man possessed, Muddy Waters casts a powerful spell. His high cheekbones and Oriental eyes gave him a certain Eastern, inscrutable quality, and at times his face even seemed angelic. He could easily work audiences into a frenzy...Muddy instinctively understood the unpretentious beauty and power in simplicity. Time and again he transformed basic patterns into blues masterpieces."

This description almost sounds like it was written specifically for the album cover of Folk Singer—when I read those words, I literally see that cover. And this does not sound like a description of someone who is acting in caricature form—Muddy's music as real and raw as it gets. The Mississippi Delta musicians from his era and culture had already paid too much debt to want or need fake anything. There is no lying in their music.

To be able to channel one's energy and focus to the point where you seemingly can alter the molecular structure of a room is a gift, and not everybody has it. It's a skill that's been passed down, from the team of Son House & Willie Brown to Robert Johnson, to Muddy, to Buddy. Muddy confessed to considering himself a smooth mixture of House, Johnson, and himself. But mostly, mainly, "it was Son House," he said. Muddy's slide and vocal delivery is taken from that vein.

By the spring of 1966 the Chess Corp. had moved into much bigger and better facilities located at 323 E. 21st Street, where they functioned fully as a one-stop operation—a music factory where they could write it, record it, produce it, press it, pack it, and ship it. The 2120 South Michigan Avenue had done its job, and due to its role, they had outgrown it. The new location would serve its own unique purpose—but "2120" was the place that actually earned the legendary status. And it's where Muddy did most of his finest work.

McKinley Morganfield died on April 30, 1983—the year that, as of this writing, marks the 35th Anniversary of his passing. The 30th of April was the exact day I originally wanted this article to be published. Alas, it didn't make it to press in time, but let it be known—I went down swingin'.

So here's to you, Muddy Waters – ain't that a man.