Lyn Stanley (photograph by Evelina Pentcheva)

Part I

Synopsis: There is some confusion in the audio world about the difference between a Direct to Disc recording and a One Step Record. Lyn Stanley has made both and she will explain in detail what they are and what is required to make each.

First, I would like to thank my fans for encouraging me to write about my experiences in the high-end recording business and the quest for audio perfection as an artist. I say quest, because this is likely a never-ending objective for those of us in the recording industry. Most artists want the best sound possible to showcase their work but it is typically bound by limited knowledge and funding-- and no matter what we do, it is subject to listener perceptions.

Background

I got hooked on audiophile quality work when I was around 14 years of age. My stepfather was an audiophile with an ample stereo gear budget. He was a chemical engineer, a PhD from Purdue University, and held a high-ranking executive position with a large oil company and spearheaded several patents for them. I could always expect great things around the Christmas "bonus" season, when ceremoniously my mother stepped into the discussion about how that bonus check was to be spent.

Typically it was split evenly between her Santa List and his audio equipment. I was always rooting for the audio toys, but now that I am older, I must admit I enjoy those trinkets my mother captured too. Sadly, years later without my knowing it, my mother "gave" away my stepfather's wonderful system upon his passing. To this day it still hurts.

My stepfather's labors with each new piece of equipment always fascinated me. He would begin by placing those boxes, filled with audio wonders, around the "cave" (AKA "rec room" ) surrounded with yards and yards of cables, wires and electronic tools as they awaited reassembly or assembly to the newest addition for his system. My stepfather selectively chose mostly instrumental music albums to play in his system (he loved Stanley Black tango albums) but he also had some vocal jazz from Sinatra and even one from Judy Garland (Live At Carnegie Hall). The sound quality was a big part of the vinyl purchase equation in our house as he was very competitive. He played singles tennis, grew a clover lawn, and even challenged his boss for the best yard and home sound system. I knew how lucky I was compared to my friends because it seemed I had the artists "live" in my home.

Lyn Stanley in the studio (photograph by Mark Lewis)

I mention these things as a background for why, when I entered the recording business in 2013, I was hooked on presenting my music with incredible sound potential. I was so fortunate in the beginning of my singing career to be discovered by Paul Smith, who was Ella Fitzgerald's pianist and musical director over a 25 year period. Paul suggested recording engineer Tommy Vacari as he had worked with him on a project with jazz arranger Sammy Nestico. I can recall after hiring Tommy asking him what was the best possible sound I could achieve with his crafty engineering. We were recording my first album, Lost In Romance, and it was a digital album. He said 192/24-bit. In 2013, with no idea what I was doing, I said, "Let's do that." After we tracked this album, I hired Al Schmitt to mix it and Bernie Grundman to master it.

Applied Technology – One Step vs Direct To Disc

Five plus years later I am about to embark on my seventh album, and it will be a Direct-To-Disc, or D2D as many of us abbreviate it. In 2017 I produced two One-Step albums, and many of my fans kept calling them D2D. So, for those who want to "Get Real" about audio, I will explain the difference. A Direct-To-Disc recording is a recording technique. Here, no mastering is done for the record. Instead, it is a live recording that is mixed on the spot by the engineer using whatever board they prefer, and that mix is immediately fed into the lathe machine to make a lacquer, the first step in the making of a vinyl record. (It can also simultaneously go into PCM [a computer ProTools™ capture], DSD, and tape-reel to reel, if set up correctly.) This means that the musicians and vocalist get tracked for every small nuance—a cough, a page turn, a comment, whatever—because it is live, and this is what goes on the record. We have to play enough music to fill one side of a lacquer with about a three second pause between each song once completed. The musicians and vocalist must be very prepared, as there is no time to make adjustments. It's live.

Once the lacquer (a positive reference) has been completed, it is express shipped to the stamper maker to preserve the recording and make the first negative impression, sometimes called the Master or Father stamper. As a reference, typically one lacquer's Father can create up to 100,000 three-step records via Mothers and offspring stampers—it's cost effective. Eventually nearly every D2D made today becomes a three-step pressed album. The reason not to use the Master stamper to produce the records is you could potentially lose your entire session if that stamper gets broken, damaged, or over used and breaks down. The D2D is a huge engineering feat and puts enormous pressure on today's musicians who are used to overdubbing their mistakes or utilizing different take edits. As Paul Smith taught me, the bands had to get it right the first or second time back in the "old" days of mid-century taped sessions, or they were not hired again. Fixes were too expensive and time consuming for the producers.

A One-Step process album is a pressing plant technique, not a recording technique. Here, the lacquer is created and a Father stamper is generated from it. However in the case of a One Step, the Father stamper creates the album you will eventually play on your turntable. They are expensive to make because they require several lacquers to be made by the mastering engineer. For the reasons mentioned above, the Father stampers can get broken, have faults, breakdown after a few pressings, and then the Father becomes useless and another lacquer must be created and used. This requires more financial investment as new lacquers and test pressings must be checked each time a new lacquer is created. Pressing plants often think of One Steps as the nightmare that is their most frustrating pressing process.

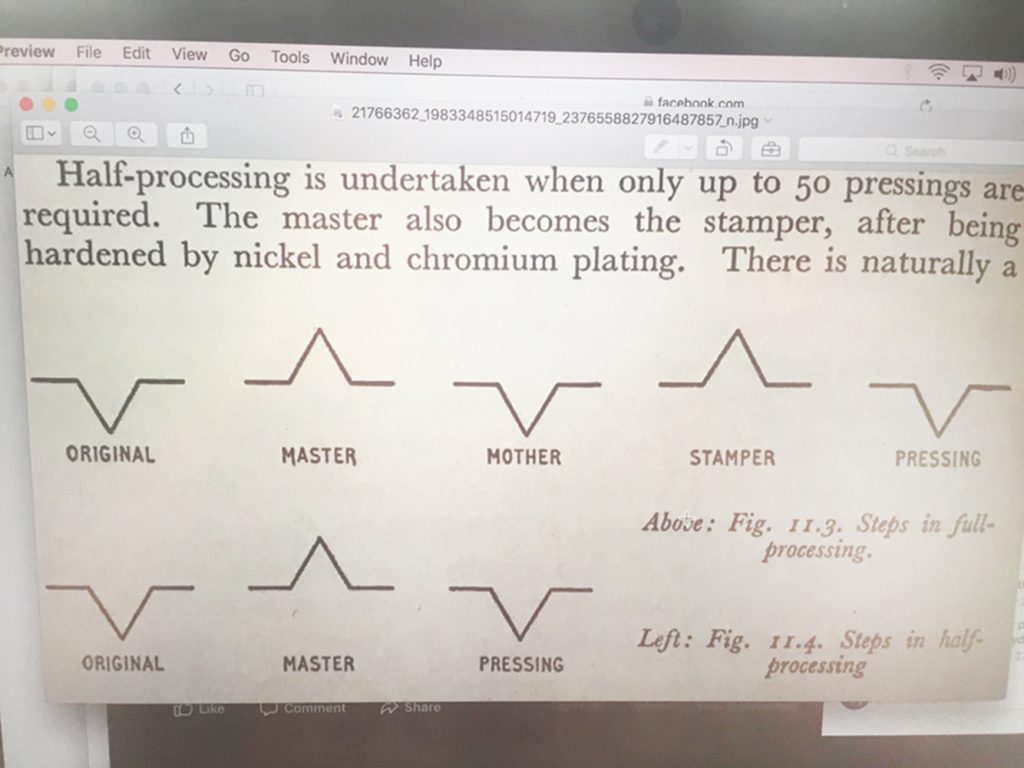

Image courtesy of Kevin Hayes, taken from High-Quality Sound Production and Reproduction: BBC Programme Operations Training Manual by H. Burrell Hadden, 1962, a Wireless World book. Published in 1962 in London by Iliffe Books Ltd.

The history of One Steps goes way back in time, even though one of today's record labels doing One Steps would like you to think they are the instigators of the process. Here is an illustration, borrowed from a BBC publication published in 1962. (Photo furnished by the audio engineer, Kevin Hayes, from his library.) Note the term "half-processing" was used in Figure 11.4 and typically associated with 50 pressings or less to be created for situations like a radio promotion of a new song (Elvis did this) back in the mid-century when vinyl was played on radio stations.

But the technique goes back to the 1940s.

Next Up…

In my next segment I will share with you the process we are going through to prepare for the actual Direct-To-Disc recording session scheduled for January, 2019.

About Lyn Stanley

An international recording artist with six albums released since 2013, Lyn Stanley has achieved notable worldwide sales in jazz, with over 40,000 albums purchased as an Independent artist with limited distribution. She has received accolades for her recordings by the audiophile community by using high profile studios, top-tier engineering talent, and noted jazz musicians perform on her albums. Discovered by Paul Smith, Ella Fitzgerald’s pianist, Smith launched Stanley’s career in 2011 by having her perform seven songs with his trio at Alva’s Showroom in San Pedro, CA. Lyn is recognized for her beautiful voice by many jazz critics, including the renowned jazz historian, Scott Yanow.

National and international jazz critics and programmers refer to Lyn as an “outstanding” jazz stylist of the American Songbook. Her website is https://lynstanley.com