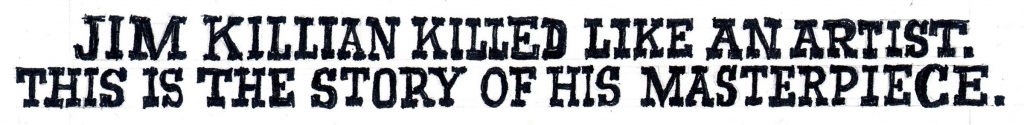

I continue to reflect on the time my father and I drove out to Old Tucson and visited the set of Heaven with a Gun, a western movie starring Glenn Ford. I'm not saying it was a great movie, but it continues to carry great import for me.

The text for the film poster reads like this...

Certain questions spring immediately to mind like "How can this be?" or "How could an artist ever, conceivably…KILL !?" I wish to look at how the plot of the movie relates to the creative process, so please bear with me as I make the following comparison:

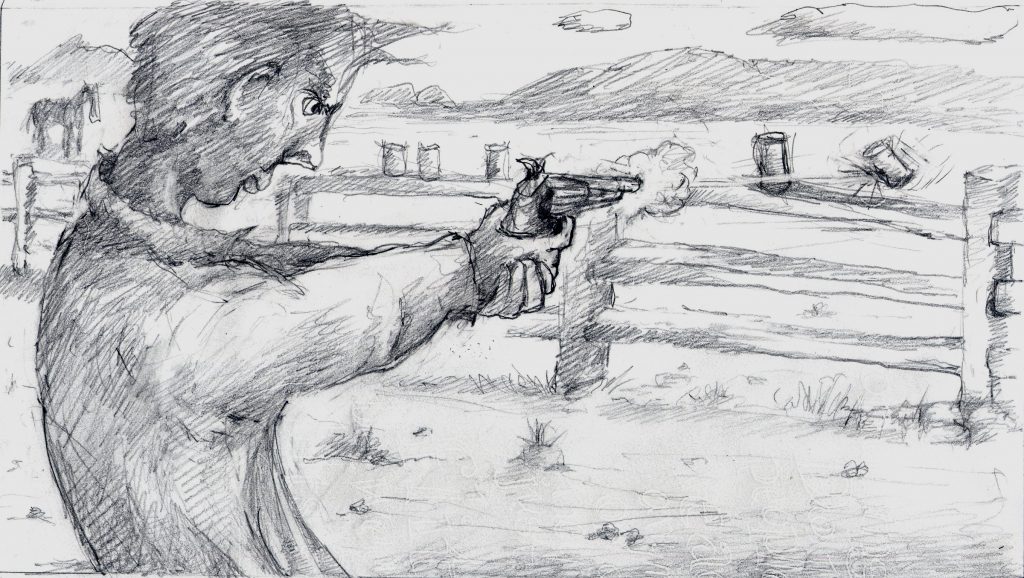

Glenn Ford's character, Jim Killian, wants to leave the life of a gunman and become a preacher. With his gun, Killian had always been able to put a stop to things, to wrap things up...with his "peacemaker." Hence, the messier, more difficult process of peacefully resolving conflict was efficiently avoided. But now, after a lifetime of such easy solutions, he found himself eschewing the gun. His heart was gripped by an inchoate vision—he desired something more

A skilled painter can kill as well—but with a brush instead of a gun. If the artist relies on technique alone when faced with the challenge of what direction to take, if they, too, desire something more—whether they're facing a blank canvas or a particularly problematic work-in-progress - the ready brush, or perhaps the sharpened pencil can, like the drawn six-shooter, effectively "put a stop to things." Very often, this can (not in every case certainly, but frequently enough) prevent the emergence of THE NEW.

And isn't that the whole point? It certainly was the whole point for Jim Killian. He was not accustomed to being a man of God. Non-violent conflict resolution was completely new territory for him.

This is how it should be for the artist as well. It's the whole point of creativity. If what results from the "creative" process is not wholly new, then we shouldn't be using the word creative in conjunction with it.

We can't create out of nothing, but what we do create must never have existed before, or we may as well slip once again back into melancholy and call what we do re-presentation, or, as Andrew Graham-Dixon, in his book on Howard Hodgkins, says "..all representational art is melancholic. To represent is, literally, to re-present. It is to attempt to reincarnate a moment, something seen and felt, that is already in the past. It is an attempt to bring back something that is irretrievably gone."

We're all up against it here. The world is a closed system. Despite our efforts to open up an aperture and bring something new through the cracks, most of the time we just slip back into re-presenting. It's a cosmic struggle; for, by definition, the "new," unless you've seen a vision, is something never seen before. It's at best only vaguely envisioned, like a vaporous dream. It has no precedent. If we knew what a "work of art" was going to be, why would we even begin? But, isn't that how it should be? The artist cannot see what their work will be. I don't believe God does, either, and I think that's been his mysterious and wonderful intention all along. In a related sense, artists cannot comprehend what they're doing. What results from creative work MUST be a joyous surprise—to both God and man.

The greatest dreams are elusive and only partially formed. The experienced artist knows this. Each time you begin to create, having only a compelling, albeit indefinite vision, all you can do is set the stage for its emergence. Then what you must do is try to woo it. The artist, in this sense, must court surprise. However, if at this critical juncture you draw your "gun," instead of letting yourself experience the awkwardness of not-knowing-quite-how-to-go-about-this, you may KILL the work, or merely re-present what's been seen before.

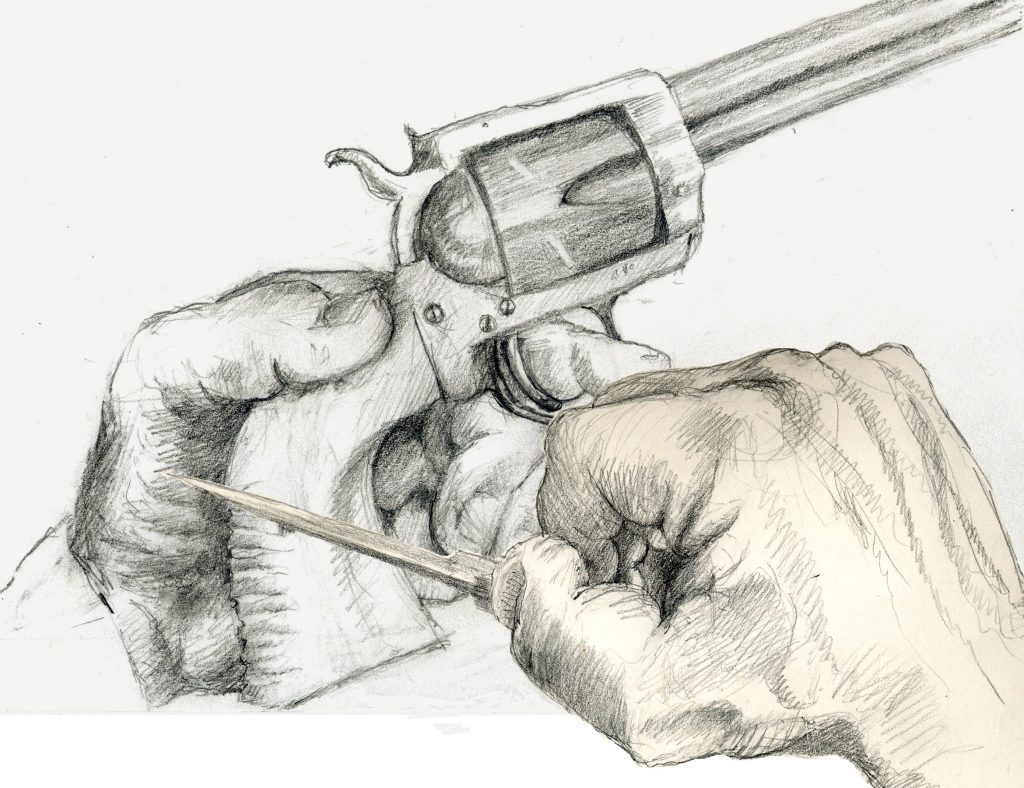

So how do we avoid this? It seems to me the answer has to do with how we use our gun. It's very important to know when it's best to keep it in the holster. I'm not against the use of one's skills—I have a hard-won few that I'm glad are available for use. But the creative act is less about what an artist can do and more about what they're open to finding out. It's less about what we have and more about what we're reaching for.

All of this is quite difficult. It certainly requires a sense of security, a modicum sense of who you are. Otherwise, you'll just "go for the gun."

I mean, Jim Killian knew he was fast at the draw. He was confident of that. Over the years he had spent many hours practicing and had gotten damn good at it, if he said so himself.

But he was seeking something larger and deeper, a dimension he hadn't yet tasted.

To answer another question raised by the film poster, yes, I do believe it's possible for an artist to make a masterpiece. However, just a moment, please. One of the dictionary definitions I found for masterpiece was "the best piece of work by a particular artist or craftsperson."

Let's be real here—there are masterpieces and..there are masterpieces. The "best" piece of work by a particular artist may still be mediocre in the grand scheme of things. It might merely be the fastest draw in the life of yet another run-of-the-mill gunslinger, business as usual.

Neither the world nor the artist would or should be seeking that result.

In the dog-eat-dog world of competition, whether you're a "successful artist" or a famous gunslinger, you always have to be looking over your shoulder, because, sooner or later someone's going to show up who is faster on the draw. Then you're dead meat. However, true creative work is not haunted by these phantoms. By definition it is unassailable, because it results in what is always both unique and irreplaceable.

There is, and can be, in this case, no contest.

Nicolas Berdyaev said, "Creativeness is always a growth, an addition, the making of something new that had not existed in the world before." He also said "Creativity is the only thing that adds." It's a breakthrough. More than simply a development, it's an addition.

Allow me to share a memorable milestone for me:

I'd been working for several months on a painting I call Mowing the Lawn. The central character in the piece, a man smoking a pipe, is mowing his lawn. I drew the image from an ad in a fifties-era issue of Popular Mechanics. To me it perfectly typified the contented homeowner caring for his property. Then I had the idea of surrounding the seemingly oblivious fellow with a jungle teeming with dinosaurs and dangerous beasts. These I drew from film stills and old monster magazines.

For months I worked and worked on the painting, but even though I rendered everything pretty much as I wanted to render it, I ended up in a state of utter frustration, exclaiming "So what!" There was nothing new about it. I'd seen it all before. The piece struck me as singularly unsatisfying. It "didn't work."

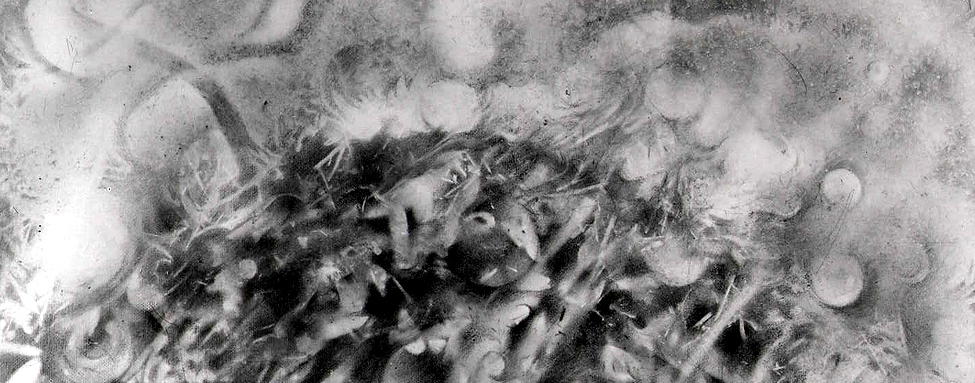

I decided that I needed to really wrestle with the thing, So, in a storm of emotion, I yanked it out to my backyard, (which, by the way, is also very much a New Jersey jungle), mixed up a strange brew of black oil paint, mineral spirits and water and started to throw the mix onto the canvas with sticks, brushes and rags. Thank you, Jackson!

At length, I stood back aghast, thinking I might have destroyed the work altogether. But in the end, I realized that I'd saved it. Something surprising happened when I reached beyond my recalcitrant capabilities.

So again...do we artists really know how to kill? Oh, yes. We are especially capable of doing so. And why is that? As in the case of Jim Killian, it's because we're so damned skillful.

Now, how on earth did we get this way?!

We're taught in school to hone our skills. And, unfortunately, it's during that early educative season of life that we begin to doubt our wonder-struck "childish" creative work, comparing these marvels to the work of "mature, skillful artists." Nothing kills like these comparisons.

I still hear the echoes: "Oh, that's g-o-o-d! I wish I could draw like that." or "That's doesn't look anything like..." or "Wow! Great job. You should get an A+. It looks almost like a photograph!"

And so we go on like this, in a sort of trance, marching toward a shimmering mirage in the distance. William Barrett, in his brilliant book on the philosophical basis for the idea of method or "technique," calls this mirage The Illusion of Technique. We keep shambling zombie-like toward the apparition, meanwhile, as the years go by, getting too skillful for our own good.

And, of course we're egged on and celebrated along the way. How pleasurable it is when people praise us! Pride rises up. We start to "believe our own press."

We've entered the savage world. Alas, not only do we find ourselves conforming to its rules, we begin to compare ourselves with others in the game.

I still remain divided about the value of competition, grades, scorecards, rankings... we develop an interest in keeping score, for carving notches in the handle of our gun, to keep track of how we're doing, our record of KILLS. When we fall into that trap, we find that we always need to be looking over our shoulder for the inevitable threat of another young gunslinger. As soon as we begin keeping score, we're fair game.

Do you recall how strange it was when you got your first report card? My memory of it is that it becomes increasingly difficult to rest in the knowledge of who you are and what you're becoming, let alone to see others clearly, and honor and respect them for who they are. We begin to see everything through the distorted lens of comparison, pride, and ambition.

So how do we avoid this trap? Like Jim Killian, in every new work, we must continue to desire something broader and deeper than what wrong-headed education has encouraged us to seek, something greater than what our familiar skills have produced so far, As William Wordsworth reminded us, "Heaven lies about us...we still can hear its voices..." Heaven on Earth is the dimension we seek. We must "break on through to the other side," although I would say to Jim Morrison if I could that then the other side becomes this side as well...

Creativity, as Berdyaev attests, is the only thing that adds. Every other human activity simply shifts things around, or re-presents them in a different context. In this world, this side of Heaven, there is nothing new under the sun. But,the new can only be brought forth by a creative act.

I find myself thinking of Jackson Pollock. His painting process has often been called an "arena." He would circle his canvas like a wrestler or bullfighter. He took immense risks with every piece. In my view, he was always grappling with the paradox we all face. He knew he had achieved exciting results in the past. He even had a rough idea how he'd achieved them, BUT..he kept pushing himself forward into strange territory, where he didn't know what he was doing. That is why he did such astonishing work.

There are others. I know the following list will be only partial, and I know I will probably forget to include people who should be on it, but I want to mention a few of those whose consistent efforts to break through barriers impacted me greatly:

My father, Gilbert S Zimmerman, my mother, Belle Zimmerman, my resilient brother and sister, Michael and Georgia, my luminous, courageous wife, Robin Mercedes Zimmerman, my brave, creative children, Matthew and Amber and their faithful spouses, and all my grandchildren, Magnus, Enzo, Isabella, Julian, and Abram, Robert Illes, Scott and Ellie Snedeker, Francis & Pam Lagielski, Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Klee, Marsden Hartley, Albert Pinkham Ryder, Charles Burchfield, Richard Pousette-Dart, Chaim Soutine, Wassily Kandinsky, J.M.W. Turner, Lee Krasner, Emily Carr, Ludwig Meidner, Maurice Vlaminck, André Derain, Howard Hodgkin, Fern Coppedge, Jack Melrose, David Robinson, Roderick and Linda Smith, Tony and Jane Tuck, Blair and Linda Stevenson, Byron Renderer, Steve Bakunas, Tim McAllister, Leon Goodenough, Dennis Childers, Todd Fadel (especially when he worked with Matt Zimmerman), Bob Sable, Tony Jones, Johann Sebastian Bach, Charles Ives, Sam Phillips, Elvis Presley, Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Jimi Hendrix, Television, Lenny Smith, Daniel & Elin Smith, Josh and Kory Stamper, Frank Zappa, Harvey Kurtzman, Forrest J. Ackerman, Georges Méliès, Walt Disney, Paul Blaisdell, Jack Arnold, George Pal, Val Lewton, Merian C. Cooper, Willis O'Brien, Ray Harryhausen, Eiji Tsuburaya, Hiyao Miyazaki, Terrence Mallick, Jim Jarmusch, The Marx Bros, Laurel & Hardy, Tom Rankin, Malachi Matcho, oh, and Ed Wood, Jr. Quite a mix, huh?

Many times they failed, days in which they could not wrest the new from the ether. But they were seized by an inchoate vision, being no longer satisfied with what they knew could be done they pressed on. Every failure to break through, every easy dispatch made them sad. They craved something much more, something akin to standing near where a shaft of light might shoot through a crack in the distant hills. They desired to witness how it would suddenly illumine previously unseen shapes.

They sought to position themselves well, so they could respond quickly and lithely to the newly limned dimensions being revealed. They were poised to respond. It was their destiny to take part in the co-creation of a whole new world.

Jim Killian was tired of the gun and its fruits. After all, he was a preacher. He loved the Lord now, and fervently led his congregation in the Lord's Prayer. Sure, he loved the earth. Sometimes the earth did require the service of a skilled gunman. But, now that he included heaven in the mix, and it was a puzzling mix to be sure. He was finding that, to triumph here, in this new era of elevated concerns, he saw it as absolutely necessary that his Earth become "as it is in Heaven."

All images by Dan Zimmerman.