Roger Skoff writes about an aspect of our hobby we sometimes forget...

I've been calling myself a HiFi Crazy for well over half a century, I've seen the birth of solid-state electronics, of stereo (it was all mono when I got started), of CDs, DVDs, and every other kind of digital audio technology. And I've also seen, over time, not only major changes in HiFi as a kind of product and a hobby, but in the meaning of the term itself.

In the beginning, when the ability to transmit or record sound was new and rare, virtually any sound that wasn't "live" was amazing. No matter how poor its quality, or how garbled or indistinct it might have been, simply the fact that it wasn't coming from a human mouth or played live on a present instrument by a human hand made it remarkable. And even before electrical recording became standard, gramophone and record manufacturers were—long, long before Memorex—claiming sound or music so real that listeners couldn't tell their recordings from the real thing.

Obviously, that was, at best, massive over-statement brought about by the same kind of wild enthusiasm that, when I was a little kid, had us excited and pointing to the sky any time we saw an airplane flying overhead. By the 1930s and '40s, though, recording, cinema, broadcast skills, and technology had progressed to the point where the sound actually did begin to have a possibility of matching those claims, and people—largely engineers and radio hobbyists, initially—began to work on what would eventually become the high quality audio we have today.

They already had the ability to record sound; they just needed to make it and its playback system better, and their definition of "better" was for the sound to be more like – to have "higher fidelity" to—the actual sound being recorded. That's where the term "high fidelity" came from, and in its beginning, it referred to recordings and equipment that would be "highly faithful" to the original sound.

Originally, "high fidelity" was an adjective—a descriptor of a kind of quality—in the way that taste, color, and smell are "qualities" of food. Later, High Fidelity (or its shortened form, HiFi) expanded to also become a kind of product—a "HiFi set," for example, or "hi-fi components"—and over the course of time, it has continued morphing until it has, by now, acquired so many meanings and connotations as to become almost meaningless. When a HiFi Show can include products and systems valued in the hundreds of thousands of dollars that sometimes really can fool you into thinking you're hearing a live performance, and when you can also find "hi-fi" earphones at the (used-to-be) 99-cent store for $1.79, what does "HiFi" really mean?

I would like to think of it in its original meaning—a practice or approach intended to replicate the sound of live music. That's what Harry Pearson, the founder of The Absolute Sound magazine, chose to name his publication after and to describe as our hobby's goal. The problem is that there is, as I've written before, there's no such thing. Or, to put it differently, there are too many such things to either count or comprehend.

In a concert hall, a recording studio, or anywhere else that live music is performed, every person in or at the venue, because they're all positioned differently, hears something different from every other person. Every musician hears the music differently than every other musician, and all the musicians hear it differently than the conductor (if there is one) or the audience. And, if it's being recorded, the recording engineer, listening through monitors or headphones, hears something different than anyone else. Effectively, his "ears" are his microphones, and he may have a dozen of them in a dozen different locations, that he's listening to, all at once.

And none of that even begins to consider modern multi-track recording techniques, where there may be no "real" sound at all because all of the musicians were never in the same place at the same time, but played and were recorded at different times (and maybe even different places), and all of their parts were mixed together, edited, equalized, and balanced later, at a mastering session to produce the first complete performance of the music.

All of that makes my original preference for defining "high fidelity" as meaning "faithfulness to the sound of the original performance" seem like a fantasy. Which original performance should it be? As heard by whom? From which location? And what if there was no "original recording session" at all, but the recording is simply a mix of tracks recorded separately? Perhaps a better—or at least more achievable—goal might be to try for faithfulness to the original recording.

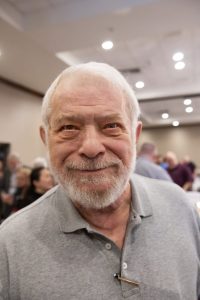

A convincing proof of this came to me in a conversation I had with an audiophile I met at a HiFi Show earlier this year. He had recently bought a new component, and in talking about it, he said that it was truly a revelation in terms of never-before-heard inner detail, greater harmonic richness, and deeper bass, even from his old recordings. That was fine and I was pleased for him, but then he went on to complain that others of his recordings still didn't sound good to him, and he wondered if there might be something wrong with his new component.

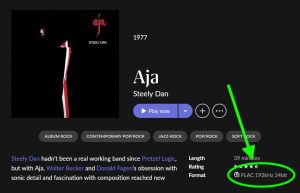

Obviously, there's no way that I can know anything about his system other than what he told me, but I do know that not all recordings are good sounding. That can be for any number of reasons: anything from a worn-out or damaged LP, to a recording of any kind, analog or digital, that was just poorly recorded to begin with, or that was good-sounding originally, but was made worse by subsequent re-mastering (think of some of the re-releases you've bought), or was a bad transfer to its present medium, or that, simply because the copy you've got is many generations from the original, doesn't sound good. There are plenty of those out there, and, unfortunately, we've all bought some.

Even so, the recordings are what we've got and what, if we want to that music, we have to listen to. So, here's the answer to that audiophile's question: In order to have a system that is truly faithful to the recordings that we play on it, it must come as close as it can to playing them exactly as they are recorded; adding nothing, subtracting nothing, and neither changing nor distorting any of the recorded information. That means that good recordings will sound good and that bad recordings will sound bad.

That's real High Fidelity at this state of the art and, if you don't like it, use your tone controls.

It's okay; if you've got them, that's what they're there for.