Bricasti Design surpasses their already world-class performance with a new Network Player option for the M1 DAC. Since the Network Player provides an option for computer based media files that is not simply a game of swapping convenience for fidelity…It was apparent it was time to undertake the journey of computer-based, networked audio.

Change is indeed scary…

"I used to be with it, but then they changed what it was. Now what I'm with isn't it, and what's it seems weird and scary to me, and it'll happen to you, too." This quote from The Simpsons episode "Homerpalooza" in 1996 neatly summarizes my fear of converting my spinning optical discs which contain up to 80 minutes of 16-bit/44.1KHz .WAV music files, to stored and categorized 16/44.WAV files on a computer-based, networked audio system.

For the better part of a decade now, a PC, or even more prolifically, a MAC, can be set up as a digital music player. More recently, stand-alone digital music servers and media streamers have become the new "it." However in audio things rarely seem to happen strictly for the sake of fidelity.

As we moved away from the original spinning disc, the LP, everything was done for convenience. It was soon possible to take your music everywhere, and when digital media files became available using various compression schemes such as MP3, further fidelity was stripped from an already questionable source: the "Redbook" audio specification (16-bit/44.1KHz PCM) for digital audio on optical discs, also known as the CD. Yet the impact on the music world of compression formats such as MP3 was tremendous, and people were carrying around entire libraries of music in a can about the size of a pack of sardines, even if it meant in terms of fidelity these digital music files were simply "good enough."

What of high fidelity audio in all of this accelerating technological madness? It was no secret that 16/44.WAV files are large and require a large amount of storage, compared to the early, digitally compressed MP3 files. Only in the past few years has copious amounts of storage for those with large, 16/44.WAV and higher resolution libraries such as 24/96.WAV and DSD become affordable and most importantly, manageable. This still leaves a few obstacles, however…

First is getting the digital information off the discs. Sure, it is all 1's and 0's as the story goes, but simply snatching the data as quickly as possible off the discs can cause errors in the data which translates into distortion. In this, the software has to be capable of error-correction and error checking as it is getting the data off the disc. Once the data is on a hard drive, neatly cataloged, and easily accessible, software needs to render that data into some sort of digital audio that a DAC to recognize and convert into music.

These complexities seem to be where a large sonic difference occurs when dealing with computer-based libraries. It does seem that most have done a pretty good job, at least to my ears, and in particular Amarra (www.sonicstudio.com) for MAC, and Foobar2000 (www.foobar2000.org) on the PC side of the universe. There is one more obstacle that computer based digital audio systems have to get up and over, and that is the means of connection to a dedicated DAC.

In most systems the connection from the computer to a DAC is accomplished via USB (Universal Serial Bus) connection. Unlike S/PDIF, TOSLINK, ABS/EBU and other forms of impedance-matched connections which minimize distortions in the time and signal domains of the PCM (Pulse-Code Modulation) digital signal, USB was originally developed to standardize a connection for computer peripherals such as a keyboard, mouse, or a dancing hula-girl that was received at the company Yankee Swap.

The dancing hula-girl is made possible by the USB cable containing a five volt power line to energize many of the universal things it can connect to. Taking said power delivery system and wrapping it around the digital data that was so lovingly preserved can be quite the pathway for distortion. USB is just dandy for smart-phones, most streaming, watching internet videos of cats, and can even achieve very good fidelity. However, it is a tough sell (though necessary evil) when considering signal preservation—yet its diversity is the very the reason why it will always find a home on stand-alone media streamers and network players with integrated DACs. We all love convenience!

Many of the newer media center digital players/servers and stand-alone library managers use the same principles as a computer based system. The advantage of a stand-alone media server/streamer over putting together a media computer is they typically have all of the finer details thought out, and have eliminated or trimmed non-essential components/processes, leaving far less guesswork as to what is required to achieve the system goal. Further, a stand-alone music server/player/library manager pays careful attention to the process: from the rendering from data, to digital audio conversion, allowing it to simply plug into a preamp, or amplifier if there is also a volume control.

All is not lost; however, as it seems in the dozens of configurations I have heard using these types of computer based or stand-alone systems, the better varieties can approach the same fidelity of a disc-spinner (CD/SACD players or transports) to a DAC. I will admit this is all a very top-level overview of where computer based and/or digital audio systems can be problematic or can win, and each topic glanced upon can warrant its own dedicated set of articles to study, so why the fuss if very high fidelity can be achieved using such means?

For my personal journey, I have been waiting to find a way to "digitize" my library where it would not be simply a form of "as good, but different." Instead I was searching for a preservation of the digital information through the entire process to assure my source would always be the strongest point in my system as referenced to what I personally felt at the time was the finest digital source available—a CD/SACD transport which renders, buffers, and corrects the information before sending out to a DAC. The first quarter of 2017 had just eclipsed when I found an interesting email in my inbox.

Bricasti does it, again…

To paraphrase, the e-mail from Brian Zolner of Bricasti Design stated that a fellow member of the local audio cluster recently added a new technology to their M1 DAC: a Network Player option that overcomes the largest obstacles of a PC/MAC based audio system by relocating all of the rendering/conversion of data to digital audio from the computer, and moving it into the M1. Brian humbly expressed he felt it was worth a listen or consideration, knowing that in a past conversation I mentioned I have been torturing myself over going to a media library/server based system.

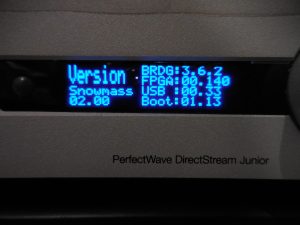

As an aside, but worth mentioning, it crossed my mind that if the Network Player option panned out into anything worthwhile, this would be the third upgrade (first paid) to the M1 since I took delivery of mine over two years ago. There is so much discussion regarding "future proof" products, and those well supported by manufacturers, yet to see this in action is a very rare example of excellence that I have only experienced with Bricasti. Here is a quick rundown of the M1.

The M1, if you have not heard of it since it exploded on the high-performance DAC scene in 2011, is well-decorated, and has earned accolades both measurably and sonically. At $8995 MSRP to get into an M1, it represents a value which many consider a top-tier DAC at any price. $10,000 will get you into the Special Edition, which contains point-to-point wiring in critical areas, anti-vibration feet, and upgraded components. Lastly, there is the Gold Special Edition, in which the Special Edition is plated in gold, topping the M1 ladder at $15,000.

The Network Player is available on all new M1 units for a $1000 charge, and anyone who currently owns an M1 can upgrade to the Network Player for $1500. This Network Player is the same as incorporated in Bricasti's M12 dual mono source controller ($15,995). The upgrade of an M1 has to be done at the factory. Bricasti re-machines the back-panel of the units to allow for an Ethernet connection to the small Linux-based computer board, which is added. Bricasti then updates the software, and the unit is gone through for a health check before being returned.

Great news for non-M1 owners: Bricasti is going to soon offer a stand-alone "box" that will contain the Network Player as a stand-alone option, the M5, for $2000. This unit will convert the network data to digital audio, and send it out via digital connection to a stand-alone DAC. This stand-alone Network Player renderer is a fantastic option to assure the highest quality rendering to an already existing system.

What's the difference?

As alluded to, the M1 Network Player is not a USB digital input taking a digital audio signal from a PC/MAC; rather it harmonizes the M1 onto a home (any) LAN (local area network) as a computer device, hard-wired via Cat 5 Ethernet cable. The advantages of this technology, which has not been widely adapted, but is gaining substantial speed, are significant.

Three major things need to happen to get data off a spinning disc and into the signal chain in a manner that an audio system understands it, as discussed earlier. These complexities have to be carefully considered when setting up a media PC; but I am happy to report that when dealing with the Bricasti M1 Network Player these details matter not, because at no point is the computer involved in any of the digital audio stream. That's because what is on the network is treated as files of "data." Turning (rendering) that data into a stream of digital audio now happens inside the M1 DAC.

The Network Player connects via a home network to look like any other computer that would be sharing data. With the benefit of common-mode noise rejection and extremely high bandwidth of an Ethernet connection, the music is sent to the M1 as simply data. In this sense, the computer gets to be a computer, not a piece of high-end audio gear.

The M1 Network Player takes on the responsibility of interpreting and rendering the data packet of music and drops it mere millimeters directly into the M1's DSP. Doing so not only allowed Bricasti to develop proprietary technology to mate seamlessly with the M1, but eliminates the need for transferring the digital music signal across multiple chassis, significantly lowering the chance for distortion.

Network Attached Storage (NAS) devices like external hard drives that connect via Ethernet cable to a home's LAN can also be controlled via laptop, or even a smart phone to send data over to the M1 network player if a dedicated media computer is not an option.

Putting together a dedicated music PC…

I chose a PC for no other reason than the accessibility and low cost. There is no benefit in running one computer type over another when setting up a music network since it is just a workhorse. I was able to get a fairly new PC, which was cycled out of service from a local company.

A large hard drive is required since uncompressed music files, in my case mostly 16/44.WAV type and high resolution downloads, are fairly large. I chose a 4 terabyte hard drive which was very affordable at $179 What does 4 terabytes actually mean beside "a lot"? To truly understand, this is a great time for a math lesson. I will keep it painless though, I promise!

A byte in computer contains eight bits of information, or eight 1's and 0's. Early on, eight 1's and 0's were configured into different arrangements and a computer understands these arrangements as a single character of text, or the minimum standard amount of 1's and 0's that can be made into something useful. There have been outliers that use a different quantity of bits to represent a byte, but that is not important here.

What is important is the understanding that 1,024 of these bytes equal a kilobyte (KB), 1,048,576 bytes equal a megabyte (MB), 1,073,741,824 bytes equal a gigabyte (GB), and finally 1,099,511,627,776 bytes equal a terabyte (TB).

An average 16/44 .WAV file for a five-minute stereo music file is a touch over 50MB. High resolution audio files in various formats can be as large as 329MB for a 24/192 .WAV file, or even 403MB for a 5.6MHz DSD (Double DSD) file of the same five-minute stereo music. Assuming no losses and every song listened to is five minutes long, 1TB of data storage will hold 21,815 16/44 .WAV files, or 2,728 5.6MHz DSD files. Bear with me, we are almost done.

CDs have a storage capacity up to 700MB. This would mean that a single TB of storage could hold about 1500 CDs. That 'sums' it up! The importance of this exercise is to know just how much storage one may need to convert spinning discs to a computer library. I have plenty of storage in my 4TB hard drive to not only hold my collection, but to expand it quite a bit, which is something that should be factored in when selecting the size of a hard drive.

The final piece of the storage puzzle is redundancy. It is important that a music library is regularly copied to a backup drive of the same size or larger in case the main drive fails. After potential months of ripping CDs and downloading files, it would be a nightmare to lose it all and have to start over. I use an outboard 4TB hard drive, stored in a different location than my house (in the case of a fire or flood) that I copy my main library to monthly.

Luckily, the remaining tasks involved in setting up the music PC are a breeze. The PC came equipped with 4GB of ram, running Windows 7 with no other software other than JRiver media center (www.JRiver.com). Including the hard drive, my new media PC cost less than $400. I ran an Ethernet cable to my internet provider's router from my computer, and did the same from the M1 Network Player. This is how the data gets around town. If there is a high-speed internet and WiFi in your home, there is everything required in terms of hardware for the network.

JRiver Media Center is recommended by Bricasti to interface with the M1 Network Player. It is extremely intuitive, allows the use of every music file type imaginable, and a license will only set the user back $50, post 30-day free trial. Bricasti has a nice step-by-step guide that was provided to me via e-mail to optimize JRiver for the Network Player.

Once JRiver is told where the main library resides, it will use the "CDDB", or CD Database on the web to provide disc and track information including cover art when transferring a CD. In the unlikely event this information needs to be entered in manually, a couple of mouse clicks will allow for modification of the disc information.

JRiver provides and app called "Gizmo" that turns any networked, WiFi-enabled device such as a smartphone or tablet into a remote control. Once downloaded, the Gizmo app asks to enter the JRiver network code for the server it will control, connects to said server, and will send the files over to the M1 for playback.

The whole process of downloading the JRiver software and Gizmo app, setting up JRiver, and ripping my first CD to the library took about 30 minutes. I am unsure it could be much easier, intuitive, or painless.

The Real Pain Begins…

Making it this far was the easy part. I have some several-hundred CDs, as well as a host of music on my laptop that will need to be ripped (that's what the cool kids call transferring a CD to your computer music library) over to the new music library. There are no shortcuts. Ripping a CD is fairly easy since all that is required is to plop the disc in the CD/DVD drive, let JRiver grab the details from the web, and verify they are all correct which is the case 99% of the time.

Sample and Mix CDs pose more of a challenge since many of them will need to have information entered manually. Each disc can take 20+ minutes to rip since it is best to rip at 4x speed or slower with additional time for cataloging if need be. Ripping at 4x speed comes as a recommendation by Bricasti to assure no errors. On a non-acoustic note—I have been getting some much needed exercise running up and down the flight of stairs between life, and the listening dungeon.

Honorable mention goes to downloading high resolution albums when purchased. Once purchased, cataloging them is as simple as selecting the music library for the place of the download.

Patience pays off!

For the better part of two of years my source has been a Jaton CD1000B utilized as a transport connected via S/PDIF out through an Esperanto Blue digital cable and into the Bricasti M1 DAC. On occasion when feeling jovial, my laptop would jump into the fray and provide some high resolution tracks. Upgrading the M1 with the Network Player option and removing the CD1000B was scary. Until the M1Network Player, my only other option for a real upgrade was a buffering transport.

I do not deal with changes to my system very well, as I tend to be cautious of falling into the upgrade loop that can be a zero-sum game of trading pluses for minuses while empting the wallet. In this sense the natural course was to A/B the Network Player with my old rig.

I decided to proceed with a track from Harry Connick Jr.'s We are in Love called "Drifting." During this initial test, there was little discernible difference despite switching back and forth for a good hour, painstakingly timing the switch from spinner to Network Player as sweat beaded forth on my brow. This result was good, as it meant the M1 Network player was not turning out to be a trade-off of fidelity for convenience.

After listening for a few more weeks and a few loudspeaker changes, I decided to A/B again with several known tracks. This music set spanned several genres from classic sax-jazz like Joshua Redman Quartet's Spirit of the Moment, to the grungy and angst sound of Stabbing Westward's "Darkest Days," and what I found was fairly surprising (though it should not have been). The M1 Network player was a significant step forward in all aspects of fidelity over my disc spinner/SPDIF out to the M1. All positive adjectives apply in this sense regarding all of the fidelity based aspects we love: Imaging, dynamics, inner detail, spatial depth, and so on. So much so, I was left wondering what I may be missing that the M1 network player is actually doing, but I have yet to flesh out. It is a very dangerous thought which will have to be dealt with in due time.

I have reached the point where the hardest work is behind me and I am enjoying my new music library. It is nice to have everything at my finger-tips, make easy and enjoyable playlists, and re-arrange my listening space to get rid of the "hard" media storage. Most importantly, the process was not so scary after all and thankfully I will be further moved by the music I so love thanks to the performance increase of the Bricasti M1 Network Player upgrade. I would highly recommend this option for anyone looking to migrate to a computer based audio/media management system for future-ready, years of enjoyment.

Prices: As listed in the review

Bricasti Design, Ltd.

2 Shaker Rd, Bldg. N

Shirley, MA USA 01464

1.978.425.5199