Roger Skoff writes about how illusions can sometimes be illusory

If I were ever asked what one thing about High-End audio was my greatest turn-on, my answer would have to be "imaging": the ability of a great system playing a great recording in a great room to make you feel as if you could actually "see" the performers playing for you. That, and its companion feature, "soundstaging," the apparent ability to perceive the size and shape of the recording venue and feel as if you had somehow been transported into it, have always been the things about recorded music that most impressed me and that I have striven to achieve in my own system and the products I design.

No, it's not the feeling that "…the musicians are right here in the room with me" that so many people—especially "newbies" or non-audiophiles seem to regard as perfection. I'm largely a classical music listener, and for a full symphony orchestra or even just a singer or violinist and a full-size Bosendorfer concert grand piano to appear in my room would either crowd me out of it or have to be presented in such a reduced scale as to lose all semblance to reality. And imagine my hard rock side—how could Pink Floyd, Queen, or Eric Clapton and a whole stadium full of their fans ever be crammed into my listening room without being either dangerous or silly? Far better if I go to them than to seem to have them transported to me!

Once your system gets to the point where, as with The Sheffield Drum Record, you feel like you can visualize the drummer's movements as he operates the drum kit, or can imagine that there is an actual person singing or playing an instrument for you, the thing that inevitably comes up is the issue of size: Do the drums or other instruments seem to be the size of the real thing? Is the man or woman singing "man-sized" or "woman-sized?" Or are they being presented bigger or smaller in physical size than it would it seem they ought to be?

As just one example of where image size was a problem for me, I once heard Puccini's opera La Tosca played on a pair of Stax "mini" electrostatic speakers, each about the same size and shape as a 27-inch flat screen TV. The speakers—sold as near-field monitors—were placed something like three to four feet apart; and although they claimed to be "full-range," they had just about no bass at all. Their imaging, however, except for size, was just about perfect, giving a tiny but near-holographic three-dimensional presentation of the performers singing and moving around the stage. It was thrilling, but to have the melodrama of La Tosca played-out by a cast the apparent size of mice (with, to top it off, high, thin voices), somehow just didn't work for me.

Another one that we've probably all experienced is what appears to be analogous to an audio version of the 1993 film Attack of the 50 Ft. Woman: On the recording being played, the lady singer, instead of seeming lady-sized, was either wrongly close-mic'd or mixed out-of-phase and appears to have a mouth running the full distance between the two stereo speakers. She's unreasonably huge and, regardless of how good the rest of the sound might be, that one thing spoils the whole performance.

Image size problems can work the other way, too: One night I was at the home of one of my industry friends, listening to a performance of the Concierto de Aranjuez (for guitar and orchestra) by Joaquin Rodrigo (HERE) on my friend's system. The sound was great; tight, detailed, and well-defined. The only thing that bothered me was that the guitar—the solo instrument—appeared much larger than any guitar ought to be. From the base of the body to the far end of the neck and headstock, a guitar can't possibly be more than three or four feet long, yet, in that recording, played on that system, in that room, the guitar sounded nearly as large as the orchestra playing behind it.

When I commented on that to my friend, he said nothing, but went into another room and returned a moment later with a Spanish-style acoustic guitar, on which he played again the opening bars of the Concierto de Aranjuez that we had just been listening to. I have no idea who the guitar maker was, but it sounded good, and my friend played it well. Most importantly, though, the guitar, belying its actual size entirely, filled the whole room with music, proving to me that the recording had been accurate and not at all exaggerated in its presentation.

That same sort of surprise happened again at a live performance by Sally Champlin, the singing sister of the Sons of Champlin rock group of years past. Sally, who had a classically trained voice, all by herself filled a good-sized room to a near deafening level, and might very well, in a recording, have come off doing just what I complained about before—filling the whole space between the speakers with her voice.

So how can that be?

Maybe auditory and visual imaging aren't—and shouldn't be—the same. Maybe the pinpoint imaging that is so highly regarded by me and so many other audiophiles is, at least in some cases, not the reality that we've believed it to be. Maybe, instead it's an artifact of all those knobs and dials on the fancy studio mixing consoles that we've all come to believe to be necessary to the best professional recording.

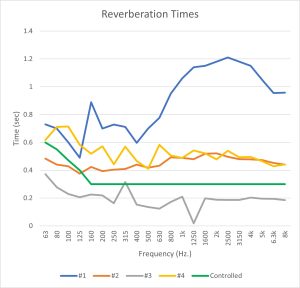

The fact of it is that stereo imaging of any kind is an illusion. The players or instruments we experience lined-up between, behind, and sometimes even in front of our speakers aren't really there, and never can be. Instead, what we have is two or more air pumps creating patterns of pressure waves that arrive at our ears at different times and amplitudes, from different directions, and at different degrees of phase. The acoustical "image" that we hear is entirely the product of our ear/brain system interpreting the interaction of those wave and triangulating them to create a mental analogy of the physical spaces involved. It's exactly the same for "natural" and "live" sound, except that natural sound originates from as many objects as there actually are, whereas our stereo sound comes from only our speakers.

And because recorded sound can be "adjusted" for timing, phase, frequency, and amplitude in recording and at that mixing console, it's possible—and even fairly ordinary—for a recording played on a good system in a good room to image better than natural sound.

With virtually every musical venue now being electrically amplified to at least some degree, (even the Hollywood Bowl is now mostly just a big HiFi set) it's hard to find truly natural, un-"reinforced" sound. It does still exist, however, and one place you may find it is at a parade. By its nature, a marching band can't be amplified, and if you listen to one, you'll find that, although its easy to get a clear indication of where the entire band is, and how and in which direction it's moving, it's nearly impossible to tell—by ears only—the position of any one individual instrument. Even at a small chamber concert, another possible place to hear unamplified music, the imaging isn't as good as it would be on a good recording. You really can't close your eyes and "see" the precise location of each of the performers, and, with eyes open, you most certainly won't hear any of the instruments sounding the same size as you can see them to be.

Sorry to say it, but imaging is a trick. Especially imaging on a multi-track mixdown recording like Pink Floyd's Dark Side of the Moon album or Yello's One Second, where things (a helicopter passing overhead, a car driving by) are moving around, forward, and back in pinpoint detail even though there was never any single recording session at all and the whole thing is a brilliantly constructed pastiche.

That's not to say that you (or I) should enjoy the illusion any less. In fact, it's all the more reason to respect and appreciate the quality of our equipment and the skills of our recording engineers. Just don't believe all you hear.

Beware the Wily Image.