Part 1: TECHNOLOGY

In the 1990s, the music industry moved from reel-to-reel recorders, both analog and digital, to DAW recording systems, i.e. computer workstations. The Alesis ELECTRONICS ADAT digital multi-track tape recorders represent a turning point in this history.

Digital Sound Recording—an audio preservation method in which the audio signals are converted into a series of pulses, corresponding to a binary code (i.e. '0' and '1') and recorded as such on the surface of a magnetic tape or optical disk. ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA www.BRITANNICA.com; accessed: 07.01.2021 ⌋

The history of audio technology related to sound recorders has a clear direction and a twist, with each change being a true revolution in the way music is produced and consumed.

It would be a journey from acoustic, analogue recorders by Graham Bell and Emil Berliner (on cylinders and records, respectively), through an electric period in which the market was dominated by vinyl records, but still with recordings made directly to the acetate, through the revolution that at the beginning of the 1940s took place thanks to the tape, another revolution, this time digital, in the 1970s and early 1980s to digital DAW systems, i.e. based on computers, today the dominant way of recording mixes and mastering music.

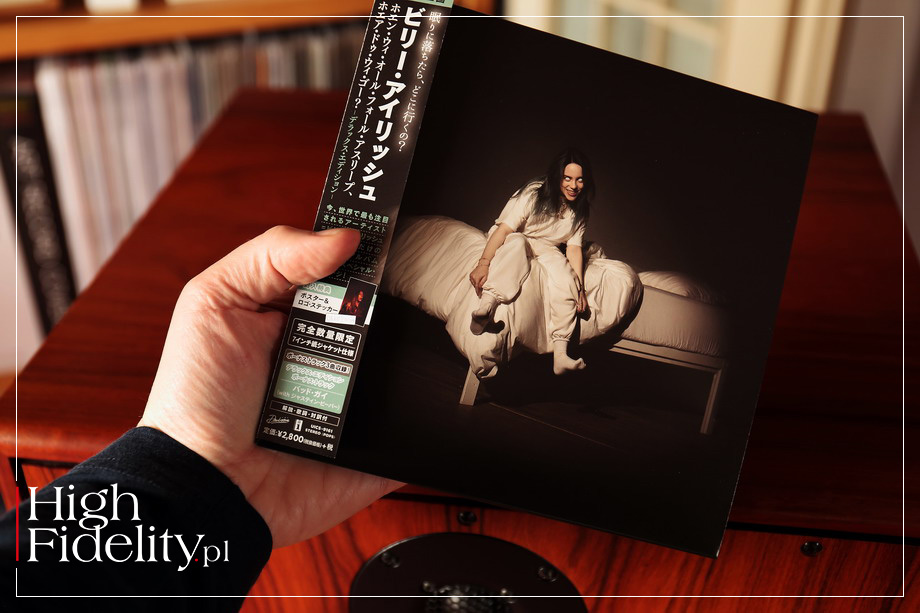

It is a story of "disappearance"—the disappearance of both physical media and their replacement with a symbolic equivalent in the form of a sequence of 0s and 1s, but also the disappearance of large recording studios and the explosion of home studios that virtually anyone can afford; Billie Eilish recorded her album When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? in her brother's bedroom (more HERE, HF № 190 • 2020, March).

The Billie Eilish album was recorded in her brother's bedroom, including the vocals only thanks to an easy access to inexpensive recording systems.

The transition between these stages did not happen overnight but it was a slow process, often with unexpected twists and a lot of surprising choices. It was no different with analog and digital techniques. As in the Modern Records, Maverick Methods Samantha Bennett writes, until the early 1990s there was a clear disconnect between home recording studios, often offering budget MIDI systems, and professional studios, using huge mixing consoles and analog or digital reel to reel recorders (p. 55).

Greg Miller in the Perfecting Sound Forever confirms it, saying:

SSL (Mixing - ed.) Consoles were the culmination of three decades of innovation in multi-track analog recording. They offered engineers almost unimaginable possibilities in shaping the sound, they also laid the foundations for digital recording and editing that was introduced in the 1990s [...] The SSL was the gateway through which the album Hysteria by Def Leppard could enter .

Greg Miller w Perfecting Sound Forever. The Story of Recorded Music, Londyn 2009, p. 168.

On the one hand, we are talking about lowering of the average quality level of music production, and on the other hand, about something that Richard James Burgess in The History of Music Production calls "a turning point in the democratization of this process" ("Democratizing inflexion point"), writing this in a section of a telling subtitle Freedom (p. 132), and to which Jonathan Sterne, referring to the topic of this article, adds:

Regardless of many economic and cultural factors, systems based on the ADAT/Mackie combination have become a symbol of the birth of amateur recordings and the entire "semi-professional" kingdom of small studios, often based in homes or other, sub-optimal acoustic spaces.

Jonathan Sterne, What's Digital in Digital Music? w: Digital Media: Transformation in Human Comunication, ed. Paul Messaris, Lee Humpreys, New York 2006, p. 102.

Burgess and Sterne related their remarks to the studio format, which outside the pro community is not widely known, and which from the point of view of musicians, sound engineers and publishers was an absolute revolution—the Billboard magazine devoted a four-page cover article to it, entitled "Budget Studio Gear Breaks Barriers."

ADAT, or Alesis Digital Audio Tape, it is a recorder first, and then the entire format of digital recorders. Eight-track tape recorders of this type recorded sound on an S-VHS tape and they could be combined into larger, perfectly synchronized systems with a maximum of 128 tracks.

The first model, called "Blackface" due to the color of the front panel, cost only $3995, and at the end of its lifespan it was sold for as little as $2995. Due to its low price and ease of use, ADAT, although developed by a small company with no previous experience with recording devices, has become a bridge between reel-to-reel tape recorders—analog and digital—and non-linear systems, based on hard disk and computer. At the time the format was on the market, that is, between 1991 and 1999, when the high-end M20 model was offered, as many as 140,000 of these recorders were sold, sometimes even 3,000 units a month!

So little known to the general public, the Alesis ADAT, and not the mighty Mitsubishi or Sony reel to reel tape recorders, became the cornerstone of digital audio. It allowed artists such as DJ Shadow (Introducing, 1996) and rapper Warren G with the Grammy-nominated, multi-platinum track "Regulate" (1994), to prepare albums completely independently, at home, thanks to which a completely new quality in music was born; to prepare another multi-platinum album Jagged Little Pill (1995) by Alanis Morisette, making it possible to come back in a big way for Johnny Cash and giving us audiophiles a live performance recording by Patricia Barber, which we know as the Companion.

Patricia Barber's Companion was recorded using ADAT 16/48.

Lets dive into the story about the Alesis ADAT. The purpose of this story is to familiarize the readers with this format, but also to make them aware that when it comes to recording music, one has to get rid of preliminary assumptions and prejudices. Here, nothing is as it seems at first glance and that is why it is such a fascinating world, rich in meanings and grey areas.

I divided the history of Alesis ADAT tape recorders into two parts. Part one is about TECHNIQUE. I will briefly recall the course of the "digital revolution," which began in 1968 in Japan, and then continued in the USA, to return to Japan. I will then describe the beginnings of the tape recorder project, tell you about its properties and how it differed from previous recorders.

In the second part, dedicated to RECORDINGS, we will take a closer look at specific CDs and recordings, we will listen to some of them, trying to answer the question whether ADAT recordings have their own character and how its advantages were used by producers, musicians and sound engineers. It will be a story of brilliant debuts, surprising returns, attempts to cope with new opportunities, as well as one of the icons of the audiophile "universe."

A FEW WORDS REGARDING DIGITAL RECORDERS

Before we go to meritum, it is worth spending a few moments to briefly recall the previous achievements related to digital signal recording. We have written about them several times, so let me recall only the most important facts. More information can be found in the articles listed below:

- TECHNOLOGY: Digital technology in the world of analogue, Trojan horse or a necessity?, more HERE (HF 155 • March 2017).

- TECHNOLOGY: MITSUBISHI ProDigi, Digital reel-to-reel recorders – from X-80 to X-880 PART 1 see HERE (HF № 193 • 1.05.2020).

- TECHNOLOGY: MITSUBISHI ProDigi, Digital reel-to-reel recorders – from X-80 to X-880 PART 2 see HERE (HF № 193 • 16.05.2020).

- TECHNOLOGY: MITSUBISHI ProDigi, Digital reel-to-reel recorders – from X-80 to X-880 PART 3 see HERE (HF № 195 • 01.07.2020).

The Pulse Modulation Digital System, on which the vast majority of modern recordings are based, was invented in the 1930s in the American Bell Labs. During World War II it was used to encode cable transmissions on the bottom of the Atlantic, connecting Great Britain and the USA. However, the first successful attempts to record this signal took place in 1967 in JAPAN.

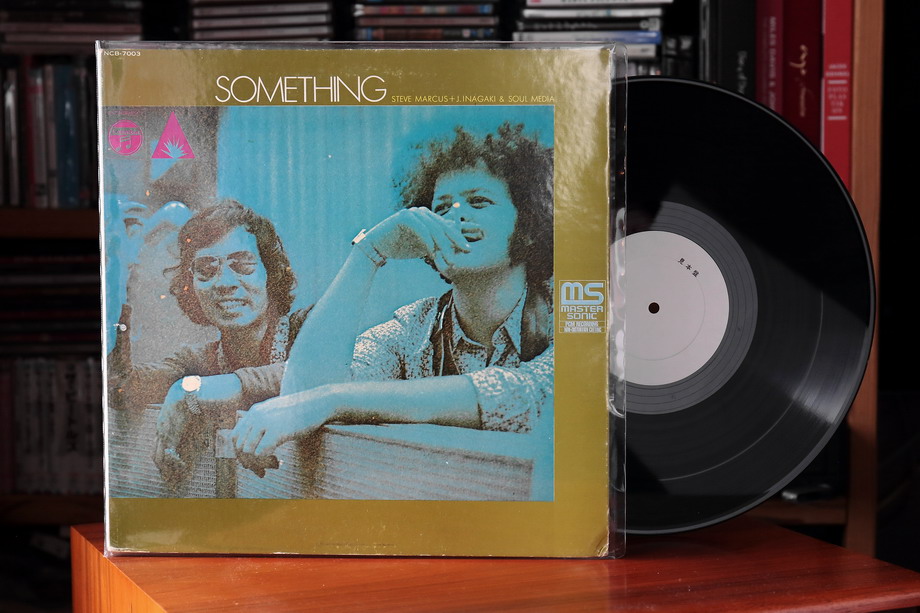

The first ever audio release recorded digitally—Steve Marcus + Jiro Inagaki & Soul Media Something.

DENON

It was there that the Technical Research Laboratory engineers of the national TV and radio network, NHK, developed a working prototype of the PCM digital recorder, and in 1968 they had a working, two-channel recorder. The system worked with a sampling frequency of 32kHz and words with a length of 13-bits. A reel video tape was used to record the signal. The company Nippon Columbia, known outside of Japan as Denon, took interest in this invention. This class of products was therefore called the Digital Tape Recorder.

That same year, they borrowed a prototype of a NHK stereo recorder and within two years conducted trial recordings and proposed significant improvements. In January 1971, the first commercial digital recording, Something by Steve Marcus + Jiro Inagaki & Soul Media (Nippon Columbia NCB-7003) was released with the Denon logo. It happened still 11 years before a consumer digital format was to be made available hence this material was released in analog form on LP.

Based on these experiences, Denon has developed its own converter that allowed them to record the PCM signal on a video tape (in the areas responsible for black and white colors). The eight-channel DN-023 system was sampled at 47.25kHz, and the word length was 13-bits. The system used a Hitachi 4-head video recorder.

SOUNDSTREAM

On the other side of the Pacific the first digital registrations did not appear until 1976. A year earlier, Soundstream was founded in Salt Lake City, Utah, by Dr. Thomas G. Stockham. He was an American scientist and inventor, also known to participate in the Watergate Commission. In 1975, he leaves MIT and founds Soundstream Inc.

He then develops a 16-bit recording system that used a Honeywell 16-track tape drive, but the electronics were of his own design. The tape recorder prototype was used in 1976 to record Virgil Thomson's The Mother of Us All. The first commercial release was an album released by the TELARC, which was the first in the USA to release an LP with a digitally recorded signal in 1978. It includes: Stravinsky's Firebird as well as Borodin's Polovtsian Dances performed by Atlanta Symphony and Chorus conducted by Robert Shaw (Telarc 80039).

In the following years, 3M (1977, USA), Decca (1978, UK) and RCA also developed their digital recorders, also based on reel transports and rotating heads, usually video ones. However, they did not dominate the market in the 1980s, but fixed-head tape recorders—from Mitsubishi and Sony. The latter in 1977 introduced the PCM-1, a digital processor with which it was possible to record a 2-channel, 16-bit audio signal with a sampling frequency of 44.056kHz on a Betamax video tape. This is how the U-Matic format was created, the most popular mastering format until the 2000s.

MITSUBISHI PRO-DIGI

However, more important for the market was the appearance of a new generation of multi-track recorders. The first fixed-head multi-track digital tape recorder to go into production was a Mitsubishi tape recorder with a system called ProDigi.

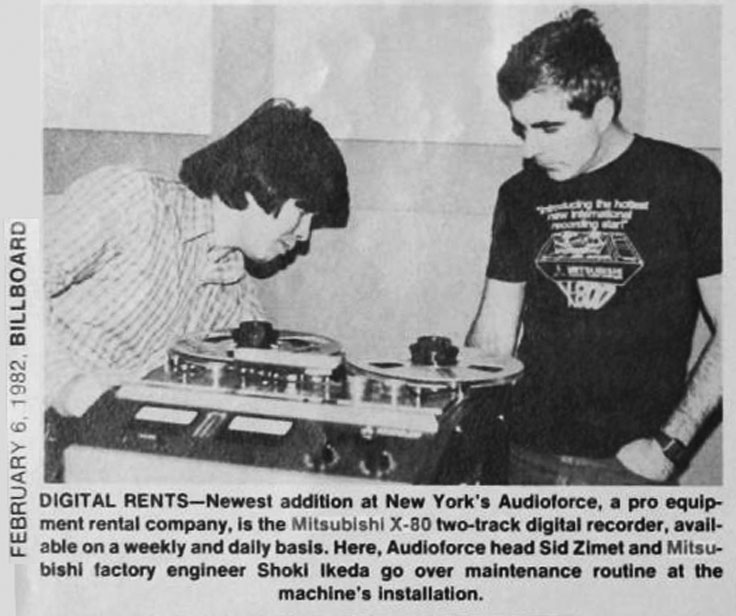

Photo from Billboard magazine placed under an article advertising a possibility of renting the X-80 tape recorder.

Interestingly, its direct predecessor was a stereo tape recorder, which became the basic mastering tape recorder for many studios. It was the SONY X-80 tape recorder, put into production in 1980, it was designed by a Mitsubishi engineer who would also be an audiophile Mr. Kunimaro Tanaka. In 1982, the Japanese proposed a 32-track recorder with the symbol X-800, using a 1" tape. The tape recorder worked with a sampling frequency of 44.1 or 48kHz and recorded the signal with 16-bit precision. It cost a staggering $175,000.

SONY

The direct competitor of Mitsubishi was Sony. In 1981 it had a prototype of the PCM-3324 digital tape recorder ready. It was a belt transport device with 24-tracks. The tape recorder recorded a PCM signal with the parameters of 16-bits and 44.1/48kHz, weighed 250 kg and cost 150,000 USD.

Sony called its system the Digital Audio Stationary Head, or DASH for short. The advantage of this solution was the low failure rate and much easier operation. Early users of the PCM-3324 tape recorder were Stevie Wonder, Frank Zappa, OMD, New Order, Dire Straits, Jeff Lynn with the ELO band, and others. The possibility of renting devices also contributed to its popularity. At the time of the presentation, the PCM-3324 tape recorder was not yet ready for serial production, and it was not available for sale until 1984. One of the first units was tested by the Dire Straits band on the Brothers in Arms.

Pro-Digi and DASH tape recorders were used in the largest recording studios until the mid-1990s. Their high price, large size, and the complicated process of signal editing, however, meant that in small studios there were still analog recorders, usually eight-track. But that was about to change, for better or for worse.

FROM AN IDEI TO CONCRETE - PRE-HISTORY

The premier of the ADAT magentophone took place on January 18th 1991 (almost exactly 30 years and a month ago) during the NAMM (National Association of Music Merchants) trade fair in Anaheim, California, although the first units hit stores only 16 months later. Already on the first day of the event, however, the tape recorder was a hit and at a time when everyone was waiting for finished products, sales of analog ½" 8-track tape recorders almost stopped, and many musicians even stopped their projects.

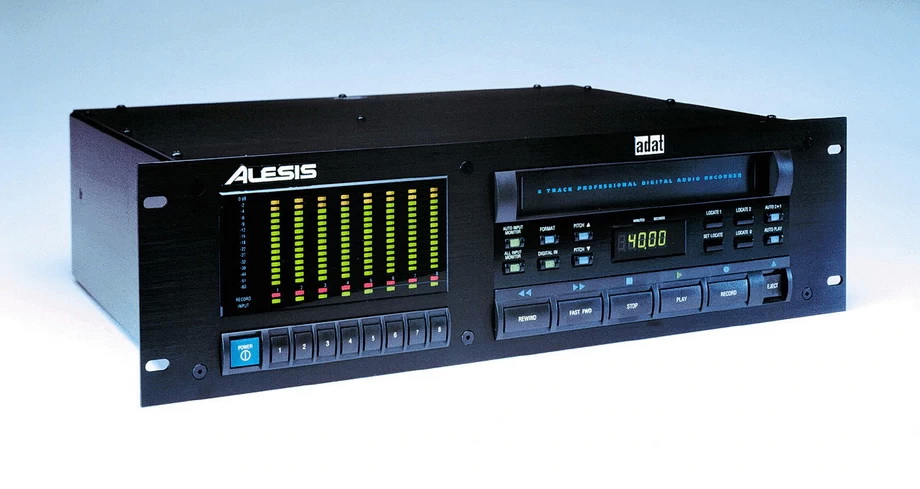

An original Alesis ADAT.

ADAT is, according to the industry magazine Sound on Sound, one of 25 products that have changed the recording world:

The Alesis ADAT recorder emerged from the heels of the two-track DAT format and at a time when the only alternative was extremely expensive, reel to reel digital equipment made multi-track digital recordings affordable. Hard drive recording was in its infancy and hard drives prices were still way too high so the only viable option was tape. […]

While the machine wasn't without bugs (Error 7, for example), it was a huge technological leap and, perhaps more importantly, the company gave the world ADAT Lightpipe, a digital link format that has become part of the digital audio environment.

"25 Products That Changed Recording," Sound on Sound November 2010, www.soundonsound.com; access: 28.02.2021

Just as important as the cost of the tape recorder was the cost of the tapes. To record ten songs (75 minutes of recording time) with a 16-track ADAT setup (two tape decks), you had to purchase four 45-minute S-VHS tapes for around $50, which guaranteed 90 minutes of recording. On the other hand, to record two or three songs on a professional 16-track 2" tape deck, it took about $160 for the 2,500-inch Quantegy GP9 reel (in 1992). For an album containing all songs (75 minutes of recording time in total), you had to spend up to $800 per tape.

The pre-history of ADAT tape recorders, however, goes back a bit further than their premiere, because back to the 1980s. Alesis was then a small manufacturer with a product that was quite successful—the HR-16, a machine percussion (that financed the development of ADAT). In 1987, at the Audio Society Engineering exhibition in New York, Keith Barr, the Alesis founder and one of the company's chief engineers visited the digital chip companies all day long. It was there that the idea for an inexpensive tape recorder, although with a professional flair, arose in his head.

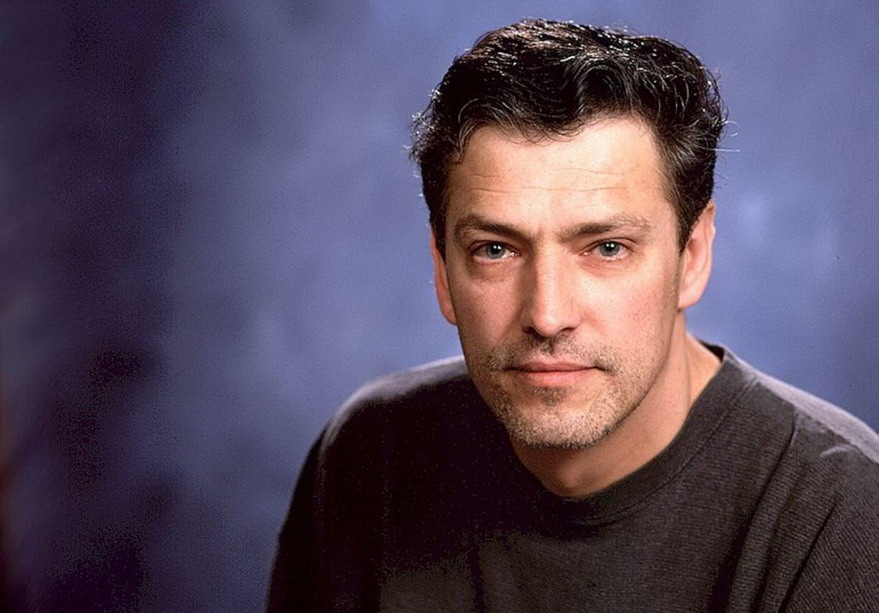

Keith Barr, the head of the Alesis and a creator of the ADAT.

The company, back then was seen in the industry as a specialist in some really nice digital reverb and effects systems, such as the extremely popular XT (1985). For many years it will be labeled "reverberation company." On the one hand, it was a depressing experience, but on the other, it allowed them to develop the new format in peace, without fear of being passed. Sony representatives, even when they saw the finished product, could not believe that "it" works.

Barr himself, in search of the roots of this idea, goes even further and in the monograph Alesis ADAT: The Evolution of Revolution talks about the mid-1970s. when he still ran the MXR company, and when he bought and disassembled a Sony digital recorder U-MATIC, based on a ¾" tape closed in a cassette and spinning heads reading it.

As he says, the scale of the project, the way the drive was organized, the heads and the electronics "completely surprised him." It was then that the thought of an inexpensive, multi-track digital recorder was seeded in his head. By the way, it must have been a bit later than the founder of Alesis says, because the first Sony tape recorder appeared on the market a bit later, in 1977—it was the PCM-1.

But let's go back to the 1987. After an exhausting day at AES, Keith Barr met his marketing team at a Spanish restaurant in Greenwich Village. The conversation concerned an idea that had been on his mind for over ten years—about a multi-track recorder "for the people." Interestingly, this "Volkswagen" of the audio industry was originally supposed to be an analog device.

Because the ADAT was not the first cassette recorder on the semi-pro (semi-professional) market. As early as in the 1979, the Japanese company Tascam introduced a four-track tape recorder, later known as the PORTASTUDIO, using a classic (analog) cassette tape. It was possible to record material twice as short as on a stereo tape recorder. The sound quality was questionable, however, and the recordings were treated as a demo at best.

PortaStudio 244 tape-recorder by Tascam.

Interestingly, there were also multi-track digital cassette recorders on the market—Akai 24-track A-DAM (1989) and a part of the system that also had multiple tracks, which also included a digital mixer, the Yamaha DRU8 model (1990). However, their prices were very high—they cost $72,000 and $62,000 respectively, and we do not know any significant album that was created with them—so they did not play a major role in the development of the recording market.

As we read in Barr's memoirs, he prepared some very interesting prototypes, along with the development of the idea of Tascam, i.e. a recorder that recorded 40 tracks on a classic cassette tape. The problem was the recording time—as short as 5 minutes. And although a prototype of a reel-to-reel tape recorder, also analogue, was developed next, a real progress was made when the Alesis team decided that it would be a digital recorder.

THE BEGINNNINGS

The Alesis Electronics at the beginning of the 1990s was a small company, without any experience in mechanics, but with extensive experience in digital coding of circuits, moreover, it was run by musicians who had very good contact with the users. The idea of using a cassette tape already showed the way in which the efforts of its designers would go.

It was supposed to be a:

- DIGITAL,

- MULTI-PATH,

- based on the CASSETTE system,

- and most of all, an inexpensive recorder.

It was no coincidence that I mentioned the size of the company for the second time, because it is crucial for understanding the phenomenon of the tape recorder, and then the ADAT format. In the 1980s on the professional audio market, 24-track analog tape recorders were experiencing their peak phase, with the most famous A80 models and the top-class A820 from STUDER, using 2-inch tapes. These devices cost, depending on the configuration, over USD 150,000, and could be coupled together to form a 48-track recording system (in the UK the A820 cost 50,000 British pounds, today a device in good condition can be bought for 30-55,000 EUR ).

As we said, at the same time, large studios were slowly switching to digital recording using two fixed head systems: DASH and ProDigi from Sony, respectively, with the PCM-3348 and PCM-3348HR tape recorders (and the Studer D827 based on it) and Mitsubishi with the X-800, X-850 and X-880 models (and the Otari DTR-900 based on it). In Japan, Denon still used its tape recorders, invented in the early 1980s, in the USA you could meet Soundstream and M3 recorders, RCA perfected their system, and Decca in the UK.

Studer D827 MkII digital recorder.

However, it was the Sony company that was emerging as a leader, whose tape recorders offered 48 tracks, were relatively reliable, and for sound engineers they were in terms of use (and habits, which is extremely important) a natural continuation of analog tape recorders—they looked the same, they were used in the same way, yet allowed for lossless copies and digital editing. But most of all—these were still extremely expensive systems that only the largest recording studios could afford.

DESIGN

When Barr disassembled one of Sony's first U-Matic recorders in the late 1970s, the cassette system on which this stereo mastering format was based, it was not yet widely recognized as credible. That changed very quickly and it became the mainstream format of this type in the 1980s and 1990s, but due to the scale of the enterprise and the size of the patent owner rather than its sonic qualities and reliability.

In the 1970s, however, U-Matic was indeed a technological wonder. It was based on a mechanism developed for vision applications, reminiscent of the original origins of Denon, Soundstream, and Decca systems, that is, with spinning heads that allowed the tape to run at a much lower speed; Sony's solution was based on the Betamax vision format.

The head of Alesis thought about a multi-track recorder designed for recording studios, but not only for them:

We were looking for something that would be intended for small recording studios [...] but also inexpensive and that would have something special about it, because we were not stupid to build a device that would not be exceptional in something.

George Peterssen, Alesis ADAT…, p. 19

TRANSPORT

In order for this to succeed, it was necessary to reach for a ready-made solution, that in addition would be inexpensive and widely available - the choice fell on VHS tape recorders in their latest S-VHS version. The video home system (VHS) was a cassette-based video tape recorder (VTR) standard for home video recorders developed by the Victor Company of Japan (JVC) in the 1970s—his debut took place on September 9, 1976.

It was a 1/2'' (12.7 mm) wide Mylar magnetic tape enclosed in a 187 x 103 x 25 mm cassette. After inserting it into the player, a special system took the tape out of the cassette and wrapped it around a spinning drum with several heads. The signal was recorded diagonally on the tape ("helical system"), and the heads rotated at high speed, so that the tape could be moved relatively slowly. The VHS was a format that won the competition against Sony's technically superior Betamax, and was on the market until the 2000s—it wasn't until 2003 that DVD sales surpassed VHS sales. The last VCRs of this type left the FUNAI production line in July 2016.

Alesis ADAT "Blackface," second version with chrome logo—other than that it was identical to the first version.

JVC's success was in part due to the fact that it was an open format, leading other manufacturers to quickly start producing their own VCRs. One of the most important was Matashushita. Initially, the production of mechanisms was reserved for factories in Japan, because only they had precise enough tools to make technically complex drums with heads, but thanks to the success of the format, the efficiency of Japanese factories turned out to be too low and they were also opened in other countries, including in South Korea. This allowed small companies like Alesis to build their own devices based on them.

Alesis recorders used the best version of the mechanics, i.e. Super-VHS (S-VHS). It was one of the systems improving the image luminance bandwidth: VHS = 200, S-VHS = 400, DVD = 500. VCRs of this type also made it possible to record analog stereo track of high quality.

I perfectly remember that to the studio of the Juliusz Słowacki Theater, where we had a Tascam multi-track recorders, materials recorded in home studios needed for the mix were brought on S-VHS cassettes by my mentor, Jozef Rychlik, composer and lecturer at the Krakow Academy of Music, as well as Bolek Rawski, composer of soundtracks for movies and for theater, author of music for the album by Renata Przemyk entitled Andergrant, then music director of the Juliusz Słowacki Theater, and so my boss (incidentally, I assisted in recording of Jacek Królik's guitar solos, as well as the sound of rototoms for mentioned record).

ELECTRONICS

Thanks to the use of the S-VHS mechanics in ADAT recorders, it was possible to significantly minimize their final price. But it was not the mechanics that turned out to be the most important, but the electronics and audio systems controlling it. So the team included:

- Keith Barr, as the head of the project, responsible for the analog section, servo motors, as well as signal decoding components,

- Alan Zak, head of the engineering department, was responsible for the organization of work, the error correction system and designed the central ASIC processor,

- Marcus Ryle, "software guy", owner of Fast Forward Designs, who set the details of recording on the tape, a system that allows synchronization of multiple tape recorders, as well as a remote control, known as LRC ("Little RemoteController"),

- Mochel Dodoic , working with Barr,

- Carol Hatzinger, who wrote all the software and designed one of the four main chips.

Barr, Zak and Ryle are listed as owners of the patents accompanying the project.

Alesis ADAT XT recorder from 1995.

The ADAT tape recorder was a complex electro-mechanical system, and this type of product has so far been the domain of the largest corporations, mainly Japanese ones, so the greater respect is due to its creators. After the first attempts to outsource production, Barr decided they had to do everything themselves. Allen Wald, Head of Sales and then Vice President of Alesis, said about it:

We commissioned the production of [tape recorders – ed.] to a company that had excellent technical capabilities and skills, but had never built anything so small before. We wanted them to build 100 units a day, but they couldn't meet the deadlines, so we had to—literally—snatch the contract out of their hands, just as the industry was calling out in one voice, "When are you going to start shipping?"

Within one month, we built an assembly line in one of our buildings, in a 35,000 square foot room. We created it literally from scratch, using sewage pipes, the outlets of which were located above the assembly stations—e.g. hand drills, etc.—and ordinary tables below them. These were the basic, simplest solutions, but we knew we had to do everything ourselves and we had to be in control of every aspect of the process, we also had to learn how to build these devices.

George Peterssen, p. 33

Keith Barr and his associates had to go out on a limb. The transports were purchased from Matsushita, also for the top model M20 from 1997, which included the most advanced VHS Matsushita IQ transport in history, used in the most expensive Panasonic S-VHS players, so they did not have to worry about them. A much greater challenge was programming all the digital circuits that were part of the device. To do this, one first had to figure out how it would all work.

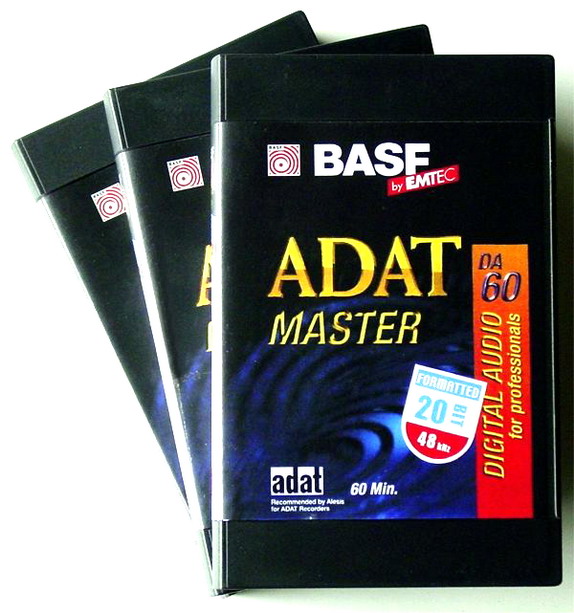

S-VHS cassettes by BASF, pre-formatted in 20-bits, hence for Type II recorders.

The coding of ASIC (Application-Specific Integrated Circuit—specialized integrated circuit) and VLSI (Very Large-Scale Integration integrated circuit) was the most expensive element of the project. Alan Zak recalls that he initially traveled to RCA's San Jose engineering lab for coding the chips where he used one of their workstations. Zak knew it had to change as it was one of the key elements of ADAT, but Keith Barr was very hard to convince to buy new equipment. The cost was quite significant—when he finally agreed, it was decided that the coding would be performed in the Alesis buildings and a workstation was then purchased which cost $500,000. Back then it was a real fortune.

WHAT ACTUALLY ADAT WAS?

Alesis ADAT was developed to be an inexpensive multi-track recorder—one device could record eight tracks. It looked like a classic 3U cassette deck, i.e. it was small, and on its front panel there was a cassette slot, similar to that in VHS VCRs and solutions known from Sony U-Matic mastering systems. On the left side there are eight VU-meter indicators in the form of bars with light emitting diodes (LEDs), and on the right - the aforementioned slot for the cassette and control buttons.

On the back there were analog inputs and outputs featuring unbalanced "big jack" sockets, as well as a 56-pin EDAC socket with an analog balanced signal. Next to it, there are also sockets for a digital optical Lightpipe link and 9-pin connections for synchronizing tape recorders. Lightpipe was a protocol developed by Alesis that transmitted eight uncompressed channels over a regular Toslink cable.

The first ADAT tape recorders, sometimes called Type 1, recorded and played back a digital signal with a word length of 16 bits and a sampling frequency of 44.1 or 48kHz (in fact, the change was smooth and covered a slightly wider range). You could record 40 minutes of the program on the T120 cassette, and 54 minutes on the T160. The tape recorder could be controlled with a small remote control, but you could also buy a large "remote," or rather a control console called BRC (Big Remote Control), which made it easier to control several synchronized ADATs.

Alesis ADAT LX20 Type II.

The latter feature was crucial because the system could be expanded either by buying another device or by renting it. As all engineers testify, the timing was flawless. This was achieved not mechanically, as in analog tape recorders, but electronically—each ADAT was equipped with a memory buffer that was synchronized with the following in the chain.

Burgess points to the combination of all these elements into one whole—a product that no one had even thought of before—and as a result, the change ADAT has caused across the music industry:

This relatively inexpensive machine offered the moderate-income producer or musician an opportunity to produce high-quality multi-track masters. In a short time, many producers moved completely or partially into their homes, small, one-man recording studios.

Engineers and producers with aspirations who could not previously afford to work in high-end professional studios could gain experience and build a discography at home or small studios. All of this was a fatal blow to the professional studio business, but also spurred more music recording.

Richard James Burgess, The history of music production, p. 133.

The potential of the Alesis tape recorder was quickly recognized by other companies. Therefore, although the name ADAT was initially used only to describe this particular, first model, when in 1993 its version was proposed by FOSTEX, the RD-8 model, ADAT became the name entire format. The CX-8 was a slightly modified Alesis Type 1 tape recorder—we'll come back to that in a moment.

In the same year, the company Panasonic, model MDA-1, presented its own version. Due to the fact that Panasonic's parent company was Matsushita, the owner of the VHS patent, its top mechanism was used in subsequent generations of ADAT tape recorders. It was included in the top model from Alesis, the MT20, as well as in the best tape recorder of this format that saw the light of day, the V-EIGHT from Studer.

CLOSER TO PRESENT

In successive years Alesis presented newer, better and better versions of the ADAT tape recorder. In the year 1995 the ADAT XT model was created, which, while retaining all the advantages of the original, added 20 new features and cost about $ 500 less than the original tape recorder; the new device had a silver front, but it would still be a 16-bit recorder (44.1/48).

The breakthrough came with the XT20 production, in 1998. It was still an eight-track S-VHS recorder, but it allowed to record a 20-bit signal (44.1/48), which was a big novelty at the time. The recorder cost $2599. Due to the larger amount of data, 40 minutes of material could be recorded on the T120 tape. All 20-bit models are called "Type II."

Top model, the Alesis ADAT, model M20.

Vicki R. Melchior in the material entitled High Resolution Audio: A History and Perspective, presented in the Journal of the Audio Engineering Society, writes that in 1994 the first commercially available A/D and D/A with 20-bit resolution converters were introduced and the professional industry started recording material in 20-bit resolution. Interestingly, the best recordings of the Telarc company, which modified the idea proposed by Stockham (Soundstream), come from this period.

The switch from 16 to 20 bits was a significant step towards better recordings. Increasing the resolution on the recorder side allowed to reduce quantization noise during D/A conversion, as well as during digital sound processing. A side effect of this movement was the creation of special algorithms that allowed to reduce the word length for the Compact Disc format: Super Bit Mapping (Sony), K2 (JVC), etc.

The next step of Alesis was—which is characteristic of this company—to offer in the same year an even cheaper device, a slimmed-down version of the XT20, the LX20 model, for which one had to pay only 1899 USD. The year before, the company went crazy and offered a flagship device, a fantastic MT20 model, costing $6999.

However, the end of the 1990s heralded a new era in which there was no room for linear (tape) systems. It is a process, as we said, slow and non-obvious. Because already in 1994 the OTARI company presented the RADAR system (Random Access Digital Audio Recorder), based on a hard drive. Bennett writes that the system looked like Pro Tools later, but its operation looked like that of tape recorders. However, it was a harbinger of the end of physical recorders, or at least their end in the mainstream.

But it is thanks to the development of the Alesis company that professional level recording became popular and accessible. Thanks to ADAT recorders, many phenomenal albums were created (which we will talk about in the next section) and the creativity of a multitude of musicians, sound engineers and producers was boosted, who were previously cut off from the market, hidden behind what we would today call an impassable "paywall" for them.

The first professional recording system featuring a hard drive RADAR, version II.

In a memoir published by the Mix magazine, which recalled Keither Barr (1949-2010), who died at that time, it reads:

By 2000, the appeal of the ADAT tape format diminished, mostly due to the rise of inexpensive disk recording systems, although the ADAT legacy lives on in the industry-standard Lightpipe digital 8-channel, fiber-optic protocol still in everyday use throughout the world. Eventually, the huge Alesis business empire began to crumble and in 2001, Numark owner Jack O'Donnell acquired the company and continues Alesis' mission of creating affordable production tools.

George Peterssen, In Memoriam: Keith Barr 1949-2010, "Mix" 08.25.2010, see HERE; accessed: 14.01.2021.

This is how the great history of digital tape recorders ended, one of the most interesting technically, sociologically and culturally, having a revolutionary impact on music - both on its recording and composition.

SOURCES

- George Peterssen, In Memoriam: Keith Barr 1949-2010, "Mix" 08.25.2010, www.MIXONLINE.com, see HERE; accessed: 14.01.2021.

- Hugh Robjohns, Otari RADAR II. Tapeless 24-track Digital Recording System, "Sound On Sound" January 1999, www.SOUNDONSOUND.com, see HERE; accessed: 19.01.2021.

- "Richard L Hess—Audio Tape Restoration Tips & Notes," Instrumentation, RICHARDHESS.com, accessed: 19.03.2020.

- 25 Products That Changed Recording, "Sound on Sound" November 2010, www.SOUNDONSOUND.com, accessed: 14.01.2021.

- Samantha Bennett, Modern Records, Maverick Methods. Technology and Process in Popular Music Record Production 1978-2000, Bloomsbury Academic, Londyn Nowy Jork 2019.

- DCSoundup, Practical Recording. Part 2: The Project Studio, DCSOUNDOP.wordpress.com; accessed: 14.01.2021.

- George Peterssen, In Memoriam: Keith Barr 1949-2010, Mix 08.25.2010, see HERE; accessed: 14.01.2021.

- Ian R. Sinclair, Introducing Digital Audio, PC Publishing, Tonbridge 1992.

- Greg Milner, Perfecting Sound Forever. The Story of Recorded Music, Gratia, Londyn 2009.

- George Peterssen, Alesis ADAT: The Evolution of Revolution, Primedia Intertec, Emeryvill 1999.

- Jonathan Sterne, What's Digital in Digital Music? w: Digital Media: Transformation in Human Communication, ed. Paul Messaris, Lee Humpreys, New York 2006.

- Vicki R. Melchior, High Resolution Audio: A History and Perspective, "Journal of the Audio Engineering Society" vol. 67, no. 5, May 2019, p. 246–257.

Text: WOJCIECH PACUŁA

Images: press mat.Wojciech Pacuła