You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback

ISSUE

23

january/february

Concierto de Aranjuez: A Bit of Mysticism?

by Max Dudious

When I realized I had tickets to an upcoming concert at which a featured piece would be the Concierto de Aranjuez, by Joaquin Rodrigo, a guitar concerto, I became excited. This piece, which has been one of my favorites for decades, has accumulated some shelf space in my collection and I thought it would be interesting to hear how each of my recorded soloists would play it. There was always something about this music that touched me and made me sad. What was it? I had to know. So I played them all for a couple of days, and I managed to hear two live performances, on a Friday and a Sunday.

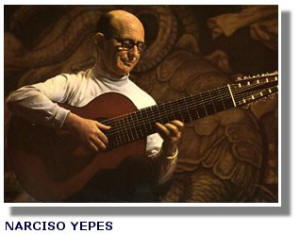

When I was a lad, an undergraduate, and a jejune poseur at that, an album of this music was released that captivated me: Rodrigo's Concierto de Aranjuez played by Narcisco Yepes, guitar, and the Orchestre National d'Espagne, the ill-fated Ataulfo Argenta, conducting. It was an early stereo LP that everyone in my know-it-all crowd was listening to that semester. We were the trendy clique of culture vultures who got excited when Catch 22 was first published. The Rodrigo was available as a London recording, but I had a few connections and got the French pressing of Decca (7.040 A), dated 1959, without knowing Argenta was already dead at 45. I thought it would likely have quieter surfaces and better cover art: and it did—a lovely Goya from the Prado, lovers under an umbrella, titled "L'ombrelle." I told you I was a pretentious creep; but isn't everyone at that age? I'm younger than that now.

There weren't any flies on Miles Davis, who later that year released his album on Columbia (now considered one of the pillars of his oeuvre), Sketches of Spain, in which a large part directly quoted Concierto de Aranjuez, if deftly rearranged by his long time collaborator, Gil Evans. The second, slow movement—the adagio—you may remember. It is hauntingly beautiful and stays with you, starting with a minor key phrase that roughly translates to Yah dah Daaah, which repeats with motivic regularity in many registers. Miles played this subtle chromatic riff through his whisper mute and it was so effective at communicating sadness that such phrases were incorporated into his ballad style.

After listening to recordings for a few days, I finally heard the piece in performance by Manuel Barrueco with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, Stefan Sanderling conducting. According to the program notes by Mark Mobley, "For years it [the Yah dah Daaah theme] was heard on TV as Ricardo Montalban extolled the Chrysler Cordoba's 'rich Corinthian leather.' And it has a starring role as a band piece in the 1996 English film Brassed Off." O.K., O.K., but what was it about this piece that makes it so penetrating, so haunting? This is definitely not your basic slow movement developed by Haydn and Mozart as the pro forma connective tissue in a concerto. This form still has many a practitioner (see David Chesky's Concerto For Flute, and his Concerto For Violin), but in Rodrigo's hands it becomes a very high example of an expressionistic mood piece.

My wife and I were were lucky enough to be in Spain one recent summer, and we took a day trip from Madrid to Toledo (due south) on a train. Along the way the train stopped at many small towns, one of which was ...you guessed it ...Aranjuez. We didn't get off and walk around, but I do remember paying attention to the scenery after I saw the sign. The town was in a region of sparse vegetation reminding me of northern Mexico , say, near Monterrey, that might be called scrub land. Aranjuez sat in the midst of a hot, dry, and dusty plain. I expected Clint Eastwood to come riding into the train station on his paint. I could imagine the town park would be a welcome spot of shade and green grass in the center of town, probably with a central fountain.

I thought more about the mystery of this music as the masterful Barrueco sat down to play it. His manner was quite relaxed, as if he might fall asleep in those passages where the orchestra played without him. But he would snap to attention on cue, and his hands would begin to move in perfect unison, with great precision, never sliding into a note, never mis-fretting a note among the tens of thousands of notes he performed, all the while inflecting each note to reveal a wealth of emotion. Barrueco has performed this piece of music for decades, perhaps playing this concerto, which is for the guitarist what Beethoven's Violin Concerto is for the violinist, with as much style and interpretative skill as any who have ever played it. Surely his playing would guide me to what was so sad and haunting about this music.

It didn't offer a clue. I was clueless. But once again I felt the powerful tug on my emotions.

I wasn't surprised at intermission when I read further in my program notes that, "Mrs. Rodrigo wrote, the music recalls 'the happy days of our honeymoon, when we walked in the park at Aranjuez.' But guitarist Pepe Romero told Saint Paul Sunday host Bill McLaughlin that this rich, sorrowful music had another, deeper meaning." Aha! It seems, "In 1939, as Rodrigo was working on the concerto, his wife was expecting their first child. They were as excited as young parents can be—she writes about the pink and white crib they brought into their apartment. But she had a miscarriage, and Romero says the composer worked out some of his feelings in the music."

Now, here's what grabs me. "The whole second movement was his way of conversing with God," Pepe Romero said, referring to Joaquin Rodrigo. "The melody, first with the English horn, then with the guitar, and then going on through all the different instruments in the orchestra [the Yah dah Daaah motive] ...is all the different passions and feelings and emotions that he feels: the love for the baby, the love for his wife, asking God not to take her." Romero adds that "the movement ends with the ascension of the soul of the baby." Thanks, Mark Mobley, for good research. I found my clue, and I thought I ought to share it.

So here we have yet another mystical musician using his very soulful music to connect with the deity, and through our listening, to open for us his connection with the deity. Small wonder that music can do this, put us in touch with the deity, find the godly within each of us and plug us in to the divine conversation. For atheists who might be reading this, think of us as each having something hardwired in our sensorum that takes us to the place where we think our most lofty thoughts. Professor Daniel C. Dennett, of Tufts University, thinks, "We have a built-in, very potent hair-trigger tendency to find agency in things that are not agents, like snow falling off the roof." What most folks call God. (The works of this "Nonbeliever" can be found on the Web if you Google Daniel C. Dennett, author, whose latest book, Breaking The Spell: Religion As A Natural Phenomenon, is just out.)

These lofty thoughts ultimately take us to, "Who are we? Where do we come from? Why are we here?" And if we can't buy into God of the Bible, then we are left with seeking scientific answers to the big questions, the big bang as the ultimate mystery. Either way, we are faced with the mystery of existence, and its corollary, death. And sometimes this comes with a burst of white light (as in Dante and, I think, Mahler), and possibly the feeling of what true mystics, and Timothy Leary, call "Universal Love," or good will toward all. The adagio movement of the Concierto Aranjuez was Rodrigo's attempt to be at one with the eternal.

This wonderful guitar concerto, written between the Spanish Civil War and WW II, is full of humanistic good will. It is firmly rooted in the Spanish flamenco stylistic idiom, yet is so universal it pops up as jazz, as brass band music, and as the sound track for car advertisements. It is another twentieth century masterpiece deserving of high stature, I feel, with its classical form and its populous touch. And it is this connection with the largest, saddest questions that elevates it from a mere tour de force guitar concerto, such as Rodrigo's Fantasía Para Un Gentilhombre. And it was this connection that raised the work in my esteem. Though he wrote lots of music, Rodrigo would never again reach the heights that the Concierto de Aranjuez attained, would never quite find the way of reaching behind the intellectual defenses into the core being of the audience with such force.

I have in-house the 1959 Narcisco Yepes recording, another 1969 version by Yepes and the Orquesta Sinfonica R.T.V. Española, Odón Alonso, conducting (DG's Eloquence, 289 469 629-2). I also have a 1984 version played by John Williams, with the Philharmonia Orchestra, Louis Fremaux, cond.(CBS MK 37848), and a 1997 version by Manuel Barrueco, the Philharmonic Orchestra, Placido Domingo cond. (EMI 7243 5 56175 2 1). They all are good. You have to be a truly bad musician to mess up a masterpiece.

The (never available on CD) 1959 Yepes LP version has gone out of print for some time now and has become something of a collector's item. Harry Pearson once offered me a king's ransom for mine. I think it is quite a good rendition of the piece, and it scores highly for sonics, probably recorded in the days of tubed mastering consoles. Vinyl junkies out there love it. The 1969 Yepe (pronounced "yeah-peth") version on DG-Eloquence is available on CD, and you can hear how well it is played, but it loses some of its sonic magic as captured on the '59 reading. This is probably due to a solid-state multi-track mixer, I'm guessing, with early CD sound compounding the errors.

The 1984 John Williams version is a bit more brisk in the faster outer movements, and a bit more syncopated in the slow second movement. I sort of like the way the music is presented, with a bit more syncopation also in the dance-like sections. However, in the slow movement, on my system, listening with my ears, and interpreting with my brain, I think the high notes on the guitar begin to sound a bit glassy, like a glass harmonium, and tinkly like a music box. This is a fault of the early digital recordings of the day. The massed strings begin to take on the harshness and graininess that we've come to expect from that generation of CDs, even on an upsampling CD player like my Marantz 8260. And, the soloist takes on the proportions of a rock star. In all, an interesting presentation, though flawed. One to own if you want to know what someone "outside" of the Spanish tradition might bring to the piece.

The 1997 Manuel Barrueco/Placido Domingo version returns to the tempos of Yepes and Argenta. It seems a bit more similar to their overall approach, forgoing the idiosyncratic tempi and rubato that Williams brought to the piece. The voicing of the piece is delicately balanced between the soloist and the orchestra, and with Domingo (one of the great tenors of his generation) conducting, the balance managed to stay sensitive to the rather polite voice of the guitar, any classical guitar, when put up against an orchestra. Barrueco is often hailed as (if not the best) one of the best guitarists of his generation. There is a felicitous match here, as both the Spanish conductor and the Cuban born soloist are very sensitive to their Spanish musical heritage. So what we have here is a partnership in restrained lyricism, and the result is one of the most beautiful and endearing recordings of the Concierto de Aranjuez I've heard, with great sensitivity to the work, especially the Adagio.

There are pitfalls in recording such a work. One thing is not getting a separate, close mic on the guitar in particular. Many other instruments, the violin, the piano, don't need a close mic as they project well enough on their own for an overhead. But if you have a close mic on the guitar, you have to set the gain realistically to capture what the guitar is playing without making it seem overly large, or loud as the whole orchestra. The EMI engineers manage to accomplish this subtle task without too much fuss, and the loudness ratio of guitar to orchestra is about what you would hear in about the fifteenth row of a symphony hall. In other words, they managed to get a pretty good facsimile of near-mid-hall sound on this one.

On this remarkable-for-its-restraint recording, I'd offer a "Good Job" to all concerned: master guitarist Manuel Barrueco for his exquisite reading, conductor Placido Domingo (translates to "Groovy Sunday") for his very accommodating accompaniment, the Philharmonia Orchestra for its delicacy, the EMI team of recording engineers for capturing all the notes all the time, and to the tenor Placido Domingo for low-balling his performance so it sounds like an uncle singing some of his favorite tunes around a picnic table at a family gathering. Uh, oh; I have forgotten to mention, there are other works on the CD. The Fantasía Para Un Gentilhombre is also enclosed, as well as six short works by Rodrigo, some songs for tenor voice. Sixty seven minutes of Rodrigo's music, offering two concerti, a few songs, and a few incidental guitar pieces (with and without accompaniment) combine to give us a sense Rodrigo's range. Over-all, a dine-oh-might album.

I think this recording is important. Great playing, good sound, plus divine inspiration is a hard-to-beat combination. It is a can't miss item for those who love the work as I do, for those who are just learning about such music, and for those who just want some beautiful music around to play while having dinner. It only becomes profoundly moving when you listen closely, late at night, alone or with a significant other. My only regret is that the recording is not available in SACD. So, if you like Spanish music, guitar music, flamenco-inspired music, some with and some without a mystical touch, grab your old lady and pasodoble on down to your local record boutique, and make sure to tell 'em Maxie Waxie sent you.

Ciao Bambini!