You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback ISSUE 2

august/september 2002

Stan Ricker Live and Unplugged: True Confessions of a Musical and Mastering

Maven, Part Two

by Dave Glackin

(This article first appeared in Positive Feedback Vol. 7, No. 6)

For those who made it through Part One of our interview with Stan Ricker, here is your reward: Part Two! For those of you who just tuned in, the introduction to Part One is repeated below, to set the stage for this portion of the interview.

Introduction

Stan Ricker has a unique combination of knowledge of music, recording, and mastering, and is one of the few true renaissance men in audio today. Stan is a veteran LP mastering engineer, renowned for his development of the half-speed mastering process and his leading role in the development of the UHQR (Ultra High Quality Recording) process. Stan cut many highly regarded LPs for Mobile Fidelity, Crystal Clear, Telarc, Delos, Reference Recordings, Windham Hill, Stereophile, and roughly a dozen other labels, including recent work for Analogue Productions and AcousTech Mastering. Stan is particularly well known to audiophiles such as myself, who were actively purchasing high-quality LPs during the mid-70s to mid-80s.

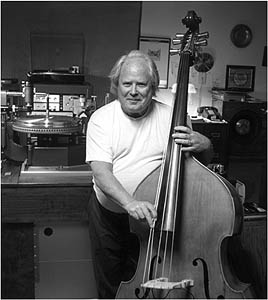

Stan's love of music has stood him in good stead in his mastering career. His long experience as both a band and orchestra conductor has trained him to hear ensemble and timbral balance, which has proven to be exceptionally useful in achieving products of the highest caliber. Stan has played string bass (both bowed and plucked) and tuba from the fifth grade through the present, and he turns out to be something of a bass nut. Watching him play standup acoustic bass in front of his Neumann lathe with "Stomping at the Savoy " playing over his mastering monitors was a special treat for me. (Writing for Positive Feedback does pay, just not in cash.) Stan also has a love of pipe organs, and is quite knowledgeable regarding the acoustical theory of pipes. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Music Education from Kansas University, but his prodigious mastering skills were self-taught.

As the capstone to his career, Stan has gone into business for himself with the creation of Stan Ricker Mastering in Ridgecrest, California. He has a state-of-the-art Neumann VMS 66 lathe with a Neumann SX-74 cutter head, a Sontec Compudisk computer controller, a Technics five-speed direct drive motor, and console and cutter head electronics designed and built by Keith O. Johnson. Stan now specializes in less-than-real-time mastering from digital sources (DAT, CD and CDR) onto 7" or 12" 33 rpm or 45 rpm LPs. The lacquers that Stan cut for me speak for themselves. He can also handle up to 14" diameter reels of half-inch analog tape at 30 ips. By day, Stan is the head buyer for the Telemetry Department at the Naval Air Warfare Center at China Lake.

Stan has lots of great stories, and is known for speaking his mind. He has been called "iconoclastic" (The Absolute Sound, Vol. 4, No. 14, 1978), "pleasantly cantankerous" (Stereophile, Vol. 20, No. 6, 1997), a "crusty curmudgeon" (by Bert Whyte), and "the most understated renaissance man of audio" (Positive Feedback, Vol. 7 No. 1, 1997) by yours truly. Stan is all this and more, as I'm sure his wife Monica will attest. I have wanted to do this interview for several years. Our first session was held in Ridgecrest on December 21-22, 1997. We continued on January 7, 1998 on the way to WCES in Las Vegas, which proved to be a refreshing respite from the hypnotic blur of countless Joshua trees whipping by. We concluded on January 31, 1998 back at Stan's place. Each time, all I needed to do was wind Stan up, let him go, and have a rollicking good time with the man who was once quoted as saying that "conformity is the high road to mediocrity."

Stan Slides Further Down the Slippery Slope Toward Becoming a Mastering Maven...

Dave: You taught yourself to do disk mastering at Keysor-Century, right?

Stan: It's interesting that you bring this up because I taught myself other things, such as playing the bass. I really didn't think about this until my wife Monica asked me the other day, "How did you learn how to drive?" I thought a moment and said, "I learned by watching my mother drive, what she did with the clutch and the throttle. The steering is self-explanatory. Learning braking distances is a matter of experience in driving a specific car that weighs so much and its brake efficiency is so much. You learn what it takes in pedal pressure to stop as you approach. Every car is different. But I learned by watching."

And I learned at Keysor-Century. When I was head of QC (1969-70), I spent a lot of time in the two Neumann cutting rooms. One of 'em was run by Dave Ramsey, who used to be a cutting engineer at Motown. He hated cutting these custom tapes of junior high school bands and stuff like that. He really used to curse and get very upset about why was he wasting his time with these Godawful crappy bands, these crappy recordings. A lot of 'em were really terrible recordings, recorded at three-and-three-quarter inches on quarter-track tape. We had to have roll-around Ampex AG 350 mastering playback tape machines. Of course, they always had preview 'cause they had to have the power to run the lathe pitch and depth assemblies as well as the cutter head electronics. Some of them were three-and-three-quarter and seven-and-a-half inch speed, and they had quarter-track head stacks on 'em. Then we had others that had seven-and-a-half and fifteen speeds and we had fifteen ips (inches per second) quarter-track tapes come in from time to time, so we had to be able to handle those. We had about three or four different tape formats runnin' up and down the hall, borrowing machines back and forth between one room and another. I spent a lotta time watchin' Dave Ramsey, and I learned from Dave, bless his soul, mostly things that I didn't want to do in mastering. Like he always put the bass filter in at 100 cycles. I asked him why and he said, "You just gotta get rid of the bass. That's all there is to it." I said, "Dave, that really pisses me off. A hundred cycles is higher than the highest string on my bass. I don't want it thrown out." He said, "Well, that's just tough shit. We're just gonna put that filter in and cut it out" (laughs).

Dave: That must have been total anathema to you.

Stan: Well, it just castrated the music. You can't have music without a foundation, any more than you can have any other structure without a foundation. The room next to him had some pretty good sound coming out of it. I walked into that room and it was occupied by a lady named Lois Walker, who had a background quite similar to mine. She had been a grade school and high school music teacher and she was a musician, and rather well accomplished. And she heard well. She heard really well. She could, especially given the limitations of that fixed-depth recording system, get a lot out of it. At least she had the sense to switch the low-frequency crossover out of the system if she didn't have program material that was gonna have a lot of low-frequency vertical modulation, which was nice. Or maybe seventy or thirty cycles or so, but not the old "Just lock it up on 250 or 500." And by the way, the crossovers would go up to 700 cycles.

Dave: Pretty gross.

Stan: Pretty gross, indeed. She produced a lot of good-sounding recordings over the years. I had been doing some experimental cutting after hours for some of the Century franchise associates, and was startin' to cut their stuff even though I was still the QC manager, and they really liked what they heard. There was a fella down in Burbank who had been a Century person, his name was Glen Glancy, and he had started mastering. He had also worked for Steve Guy at Location Recorders, I believe. He set up a company called United Sound Recorders in Burbank that specialized in mastering, and did a very good job. He heard some of the stuff I'd made and, as they say, he made me an offer I couldn't refuse, so I went to work for him (July 1970 - August 1973). All the Century franchise associates that had been mastering at Keysor, deserted Keysor and went to United Sound for mastering. Eventually Glen was running two shifts to keep up with the demand. Then, Keysor called me up and made me another offer I couldn't refuse, to go back and run their recording department. There were seven recording rooms there. I said, "Okay, well, I'll go back and do that." By this time they had bought some Neumann VG 66 cutting amplifiers and an SX 68 cutter head and moved the Westrex stereo cutters onto two new Scully lathes. So they had two Scully Westrex stereo setups and two Neumann stereo setups. I take it back. They didn't have seven cutting rooms, they had seven engineers. They had five rooms and they also had a mono Scully lathe with a Westrex 2B mono cutter head on it. That lathe would cut inside out as well as outside in, truly an oldie but goodie. It was actually on that lathe, run by a lady by the name of Pat Marquez, that I would practice. She would say, "Here, you wanna practice? Here's a pretty good take." And she'd have some jazz tape or something, because Armed Forces Radio did mono stuff as well as stereo stuff. So I'd practice cutting on that. That really just whetted my appetite.

Dave: There's the old British system called Sit by Ethel, where you learn by osmosis.

Stan: Yeah, you just watch.

Dave: So your variation on that was Sit by Lois.

Stan: Yeah, sit by Lois and sit by Dave and sit by Pat Marquez.

... and Perfects His Craft

Dave: During all these years you were learning and refining your technique.

Stan: And learning what I wanted to do and those things I didn't want to do. The really obvious thing to me was the improvement in sound when you just bypassed the limiters. That was really just so doggone different, so marvelous. It made things sound closer to live broadcast.

Dave: When Tam Henderson interviewed you for The Absolute Sound in 1979, you gave a quote that is my favorite from that article, which is that "Conformity is the high road to mediocrity."

Stan: You mean I had the brains to say that then? That's certainly how I feel, and I'm just absolutely amazed that I had the foresight and intelligence to say that at that time. I wonder how long I practiced that one! I really believe it, because you read and you find out that the people... I mean, I think about the people here at China Lake who really made a difference. By God, they were not people who just sat by and did the status quo. They felt convinced of what they were doing, and they were willing to take a risk. If you don't believe in it well enough to take a risk then you probably don't believe in it very well. So yeah, I have been willing to take risks when we can make this really good. If we're careful and do this right, this should really work.

Less was more. Many times less was more. Less signal, less stuff in the signal path. If you go into any mastering facility and look at where the signal goes before it finally gets to its destination, some of the routes are appalling. Going through back planes and stacks of circuit boards that are so close together that the designers never thought that these things, under certain conditions, are capacitively coupled and affect the high frequency response rather drastically. That was one of the major things wrong with the VG 66 Neumann cutting amplifiers. They've got many modules that are plugged in like this (Stan goes into the electronics portion of his lathe) and the plane of one would be right next to the other, like this close, and they'd be capacitively coupled. And weird things would happen that wouldn't happen if you pulled the module out and put it on an extender card. When you take the extender card out and just put the module back in, why does this thing start ringing or oscillating or doing weird things at certain frequencies? Why does it sound different?

Dave: So when you went back to Keysor-Century and they got all the Neumann goodies for their Neumann lathe, was that the first computerized lathe that you worked with?

Stan: Yeah, that was the VMS 66 lathe, SX 68 cutter head, and VG 66 amplifier rack. The VG 66 amplifier rack was solid state, 100 watts per channel and the computer for pitch and depth sampled amplitude and phase information, basically. It didn't deal with absolute polarity. If there was a voltage, it just made a displacement. It didn't care which way the groove went. So on that point alone it tended to waste space. And the other fact was that it divided the turntable surface or rotation into quarters. That is, the computer operated once per quarter revolution. So, whatever it was, the biggest excursion in that ninety degrees told the computer, "Okay, you can allow space for that biggest one and all the other stuff, although it may have been tiny, the grooves were still far apart and so forth." Then John Bittner came along. He was a mastering engineer, and still is a very good mastering engineer, in Phoenix. He cut records for Wakefield record pressing. Wakefield was a pressing plant that used Keysor vinyl and made very good, quiet, flat records. They pressed a lot of the Angel product. John Bitner designed and built the Zuma computer that so many Neumann lathe owners have now. It divided the turntable revolutions into, I believe, sixteen sections, and it was amplitude, phase, and polarity conscious. So it saved quite a bit of space over the original Neumann computer, although it would waste space in the bottom end. Later versions of John Bitner's Zuma computer addressed this wasted space problem in the low end, and they're quite good.

The computer that I have on this lathe is called Compudisk. Compudisk was built, I understand, by a gentleman by the name of Jerry Block, but it was designed by George Massenberg and Burgess McNeil. It's a very comprehensive computer. It will, when necessary, just stop the feed screw entirely in order to conserve space. It's polarity, phase, and amplitude conscious, and it divides the disk into thirty-two elements. One of the neat things about the Compudisk computer is that once you decide how many lines per inch you want in your lead-in and how many lines per inch you want in your lead-out and so forth, it immediately does that at any speed you're cutting. All this stuff goes into this data bank and it tells the feed screw motor what pitch to run for all the different speeds. It will run at sixteen-and-two-thirds, twenty-two-and-a-half, thirty-three, and forty-five. It'll cut in all four of those speeds. Of course, the turntable will go those speeds, too. Also the turntable will go at seventy-eight. And if I had a seventy-eight stylus for that Shure cartridge in that Grace arm, I would play for you some of my old 78s with organ music that go down to 27 cycles. I'd like you to hear first hand that some of those old records did have some woofers on them.

Dave: Well, if Clark Johnsen's reading this I think he just woke up (laughs), being another 78 lover.

Stan: People tend to forget about 78s. They were, by any description you care to throw at them, direct-to-disk records. They were very direct-to-disk. Of all the things that were ever recorded on 78, I tend to think that some of the most exacting stuff was Spike Jones recordings, because there was so much stuff going on in that percussion section, they had so many things to work in, and it all had to be gotten in by the time the lathe is gettin' down to the lead-out. I mean you're talkin' about just one or two turns, one way or the other, in terms of getting all the music, the whole score onto the record. It's really amazing. With classical it was no big deal because they ran multiple lathes, the orchestra just played, and the lathes overlapped in the recording. So you could do the symphony almost unbroken. It's just where side one ended and side two took up, just start one, stop another, and so forth. But when you're doing complete songs, complete compositions, on one side of a direct-to-disk, that's, to me, the height of difficulty. And I'm really amazed that so many of those early recordings came out so well.

Dave: You're probably glad you were not working in that era.

Stan: Yeah, that would have been really messy. The wax and in the early days of lacquer cutting, too, they didn't have heated styli, they didn't have vacuum-chip pickup assemblies; people standin' there with paint brushes sweepin' the chip away. I mean that had to be a shitty job! I don't know that I would have been so keen on doin' that. Never know. That's probably the first thing I would've invented, some way to pick up that stupid chip (laughs). Actually, somebody did. I don't know who did, but that's a real major step forward to collect that, the part of the groove. I mean, obviously you cut the groove. The part you cut out has to go somewhere, and at 78 it collects at quite a rate of speed.

Dave: So back to the inevitable march of time. In 1973, did someone make you yet another offer you couldn't ignore, to go to Location Recorders?

Stan: Well, Steve Guy did. At Keysor-Century, things were a bit more political than I liked. Just a lot of politics goin' on. For instance, they wanted me to teach the other cutting engineers how to get the sound that I was getting. And I said, "Well, to me it's simple. You listen to the tape and the tape needs treble or has it got too much bass, make it sound right, now record it. That's all. Just do it." And they couldn't do it, except for Lois Walker. The rest of 'em were unwilling or unable to, "Oh no, we'll dump the chip, or we'll blow the cutter head," or something like that. Well, it wasn't what you'd call a union shop, although they had to account for all their time and they had to account for their production and all this kind of thing. So it was not really a closed-shop type mentality, but you couldn't afford to blow a number of sides because if the production was down, the costs went up. It was just that simple, and they didn't like that. I can understand that, but the management wanted me to teach 'em. I guess what they didn't want was me masterin' all the, I mean I was doin' Jack Renner stuff, and I was doin' Jerry Lewis from Arlington, Virginia, and I was doin' Herb Streitz from up in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area. And I was doin' a fella by the name of John Stewart in Dallas. And these were all high-volume guys who demanded good work. They demanded better than average work. These record orders would come in the morning and the ones that were gonna be difficult or had the best chance of sounding the best, I just took 'em and I did 'em myself. As supervisor I had kind of that option but management just wanted me to supervise, they didn't want me cutting. I said, "Well, the only way I know how to do this is to teach by example. If they want to hear a product that sounds good, then, first of all, we have to have a product that sounds good. Then we can use it to have them all listen to it in their own rooms and say, "This is what we can do with our equipment if you're willing to be just a little more careful rather than just slap it on, and go for it," somethin' like that.

So anyway, Steve Guy offered me a job because there were an awful lot of people who were leaving the Century recording franchise. There was a company called Mark Educational Recordings in Clarence, New York, which was run by Vincent Morette. Vince had been one of the highest volume guys in the Century franchise, but he had grown dissatisfied with the Century recording and pressing quality and so forth so he had decided that he'd form his own recording corporation, so to speak. He took on a lot of these higher-quality, higher-volume Century guys in Mark Recording, and Steve Guy was doing a lot of their mastering, so as that started to build up Steve asked me to come down there and record a master for him. I thought that was really cool 'cause LRS at that time had a good reputation and Steve was a really nice person. By the way, he's the one who introduced me to the Sapphire Club.

The Development of Half-Speed Mastering

Dave: Stan, you worked at Location Recorders from early 1973 to November of 1974, then for Keysor-Century/AFRTS for one year, and then you went on to the JVC Cutting Center in Los Angeles, where you were the chief mastering engineer and where you developed half-speed mastering. Can you tell that famous story once again?

Stan: Well, I can, but to go back to Location Recorders with Steve Guy, one of his most reputable clients was Hal Powell of Klavier Records. Hal often had these marvelous imported European tape recordings that he brought by to do disk cutting on. One of 'em that he brought by was Sir Vivian Dunn directing the City of Birmingham Orchestra. I think it's a Sir Arthur Sullivan composition, but I don't remember. It's one of these things I see in Chad's catalog listed as a really marvelous re-release, or whatever. I cut the original of that, and one of the things I remember about it was that it was conducted by Sir Vivian Dunn and I had met Vivian Dunn in Lawrence, Kansas when I was teaching at the Midwestern Music and Art Camp. Vivian Dunn's the one who gave me that baton that's in the house and that I still use with my China Lake Band and things like that. Very long baton, very whippy. He gave me that baton, and I have kind of treasured it over the years, so when I came across a recording by him I thought, "Boy, I want to give this special treatment."

When I was invited to go to JVC (Stan worked there as Chief Engineer from November 1975 to November 1979), they had an engineer there, Darryl Johnson, who wanted out of this half speed (quadraphonic) stuff. It drove him nuts. Also, Brad Miller was driving him nuts. That was the first I knew of Brad Miller. Brad is the original Mobile Fidelity. He was a client of JVC Cutting Center, and was into quadraphonic when it first appeared, you see. Darryl used to cut a lot of quadraphonic stuff for Brad and it, for various reasons, turned out not too well, primarily because it was being pressed on American vinyl. Later on, I conducted some wear tests and I found out that the thirty kHz carrier that was engraved on the CD-4 records on American vinyl, you played it once and you tried to play it again you couldn't even recover the carrier. And on the JVC vinyl... mind you, these are stampers from the same lacquer master, one set pressed in the United States, another set sent to Japan and pressed there. On their vinyl we could play back a hundred times and the carrier was down only three dB after a hundred plays! That was one of the primary things that did in CD-4. Quadraphonic in general, the CD-4 specifically, was only successful when it was pressed on the Japanese vinyl. American vinyl just wasn't hard enough, didn't have good wear characteristics.

CD-4 was dying, all the quadraphonic stuff was goin' down the tubes, so to speak. I think if it had been used intelligently instead of somebody scoring a rock band with the damn drums behind you, if they'd done some logical things, musically, instead of illogical things like that, to try to demonstrate a method of reproducing sound, if they just used it like they do nowadays with these 5.1 surround sound concepts where they've got the ambience around, most of the stuff's up front, it would've been a success. But the way the engineers and producers misused that medium at that time, it was doomed to failure. It was very unsettling to sit in the middle of a room with four loudspeakers around you and hear a lot of music in front of you and then some damn guy starts strummin' a guitar over here behind you, or a drummer starts workin' out behind you. The first thing you do is turn around and talk to the loudspeaker and say, "What the hell are ya doin' back there? Get up here with the rest of the band." I mean, it was totally unnatural. A lot of that stuff was totally unnatural, just from a musical standpoint, to say nothing of the aesthetics of it. Hell, they'd have the drum set back there, recorded in an entirely different acoustic environment than what these guys up front were in. It just didn't belong. It was just being misused and, sure, everybody was just learning about quadraphonic or surround in those days, but I can't believe there were so many producers who were just out of touch with reality in terms of what real music in a well-integrated, acoustic environment was like.

Dave: Right. I remember hearing that around 1971 or 1972 in a place in Pasadena. I think it was University Stereo. They had four Bose 901s set up, powered with some McIntosh and Marantz equipment. The Boses of course, were lousy enough to begin with, and in quad it was...

Stan: (Laughing) Four times as bad, right?

Dave: ...really screwed up.

Stan: Yeah (laughs), four times as bad!

Dave: It just made you want to rush out and buy it (both laugh).

Stan: Enough to make you throw up. I remember one time somebody asked me about that. One of the worst things about quadraphonic, especially CD-4, was the signal-to-noise ratio was so bad that about the best you could get out of it was 35 dB signal-to-noise ratio. Well, I mean, on an unmodulated lacquer, the noise is down about minus seventy-two. Even the government specifications for stereo phonograph records are minus 55 dB minimum for noise in stereo and minus 57 in mono, and the best these quad things could do was minus 35! So they were at a terrible disadvantage to start with, plus the stuff was being cut on systems that were transformer-coupled and there was absolutely no bass. I remember hearing some Nicholas Harnoncourt. God, I love that orchestra. I mean, you were so totally involved in that orchestra the way that they miked it, but it's like they sent the ‘cellos and basses out on a lunch break. All you ever heard was violas and violins. You just never knew the rest of the orchestra was there. The low end was just not there.

Dave: So you converted CD-4 to a half-speed mastering process.

Stan: Converted the CD-4 mastering machinery because I saw, I envisioned one day comin' to work... I thought, God, if we don't get any clients pretty soon, this place is gonna shut down, and we're gonna send all this expensive machinery back to Japan or just sell it off. I won't have a job and that's kinda bad dookie. What can I do to help save this? So I started doing some experiments with some of Brad Miller's tapes. That was on the same Scully tape machine that's in here (in Stan Ricker Mastering) with four-track, half-inch heads on it. Just turned off the FM modulation, the carrier generating equipment, and raised the cutting level six dB. With its four tracks, the left rear and the left front folded together to make this left channel and the right front and the right rear did the same thing, so you combine the two and two. In fact, you didn't have to combine them at all, they combined within the recording equipment themselves. You disabled the carrier so if you turned yourself ninety degrees to the side of these two loudspeakers, you just got mono, but between that mono and this mono you had stereo. If you went into CD-4 you had stereo this way, stereo this way, stereo this way, and stereo this way. That's what you want and that's what you have. It makes a really, really good-sounding record, with a great dynamic range. One of the things that made that particular system unique was that JVC had requested, and Neumann had built into the cutter system, a crosstalk-cancellation device. In high frequencies where they would take a certain amount of the 10K-and-above energy and invert the polarity and inject it in the other channel. This is because of crosstalk, not so much in cutter heads but in cartridges. So when you cut stereo stuff on this system, when you had a crash cymbal or a ride cymbal that was hard left or hard right, it stayed there on playback. Interestingly enough, in this system here that Keith built, he incorporated that concept into the cutter system after I told him about this thing that was in the JVC system so many years ago. He said, "Yeah, and it makes instant sense, you know." I really didn't realize that it was incorporated into the system until I started looking at some of the electronic schematics this morning.

The Mysteries of Half-Speed's Gorgeous Sound Revealed

Dave: You've told me that some of the things that you like about the sound of half speed is that it has lower distortion, better transient response, and improved high end, and that one of the big benefits is that when you drop the frequency band by an octave, it requires only one fourth the amplifier power to cut the record.

Stan: Yeah. You drop it by an octave and you also double the length of time it takes to put the signal on the record. So you've got two factors of two.

Dave: How is it possible for a lacquer cut at half speed to sound better than the master tape from which it was made? At first blush that sounds like a bit of a conundrum, but I understand that it is really not.

Stan: Quite a condom, you say (laughs)? You've got to realize that it sounds better played at real time than the analog tape does, played at real time. One of the primary reasons for doing the half-speed analog recording is that more tape playback problems are solved by playing the tape back at half speed. Hysteresis problems in the playback head, the slew rate problems in the tape head preamplifier. The resonance peak of the playback head circuitry is a fixed resonant peak, so in terms of the music you're transcribing, it's moved up an octave and is way out of the audible range of any of those high frequency resonance circuits. So when you consider all of this, therefore, the signal is cleaner as it passes through the system, especially anything that involves cymbal crashes, brass instruments (trumpets, trombones, etc.), other high frequency-type tone bursts. At half speed they go through the system quite easily and are not apt to cause any kind of power supply or slew rate distortion, or TIM, or any of this stuff. So if you can cut a disk that way and you have a really pristine disk playback system, like many audiophile folks do, then you get to enjoy the advantage of a record that was cut from a tape in a way that you get away from a lot of these tape playback anomalies. The tape record and playback anomalies are part of why Doug Sax did all those marvelous direct-to-disk sessions. The tape machine itself is a huge stumbling block in the transparency of the audio, of the music, of the sound. The transient response isn't there, and with tape, as with practically every recording medium, it's easy to get the signal recorded; it's harder to recover it. So, if you recover it at half speed, transfer onto another medium, and you have a really good playback of that other medium, the phonograph record, then when you compare the analog tape played at real time versus the lacquer played at real time, the signal off of the lacquer has managed to come out without all the problems inherent in real-time tape playback.

What you're really hearing is the signal with problems and then the signal without the problems. That, to me, is why half-speed mastering was such a phenomenal process. I used to think that this was because of the lower amount of power required at half speed, but I'm convinced now that it's about a 70/30 situation. Seventy percent of the improvement is due to scanning the tape at reduced velocity, and not driving those tape head preamplifiers into gross distortion. We hear people say, "Oh yeah, that's just analog tape overloading, or whatever," whereas, in reality, we recover it without those problems. That's why it's been such a tremendous treat to find the really good stuff buried on some of that old Scotch 111. It really is quite possible that the disks, under those conditions, can sound better than the master tape played at real time. It's amazing to listen to a good analog tape at half speed, one that's truly wide range, low distortion. I mean, it just blooms in front of you. It's just unbelievable. I think of the experience I had listening to a MoFi re-release of Russian music, with the Russlan and Ludmilla Overture in D Major (MFSL 1-517). I mean it's full orchestra, the orchestra's just going a mile a minute, just lickety split. At half speed the recorded sound just opens up, and wow! It was not a Dolby tape, and that was important. It was pre-Dolby for Decca. Just such a wide-open spaciousness. When you played it at real time it tended to get congested, but the record didn't come out that way. The record has the spaciousness of the original tape, which you could only really perceive in the half-speed mode. There's a lot to be said for half-speed transcription. I tend to like, right now, this two-thirds-speed thing because the bass frequencies seem to be better integrated with the midrange and treble. It didn't always happen at half speed.

Dave: I understand that one problem you had with the JVC system was that it lacked bass due to the transformer coupling. So, in your usual way, you made a few slight modifications to the system.

Stan: Mmm hmmm. The usual way was to bypass this multi-jillion dollar JVC cutting system entirely and just go from the Scully tape machine through the minimalist part of the JVC console, direct to the Neumann cutting rack. Then, we went even a step farther. With Zubin Mehta and the Star Wars album, John Meyer built a line driver amplifier box with which we could take the output of the Scully tape machine and run the audio signal through the Meyer line driver box and directly couple the output of that, by way of BNC connectors, directly to the Neumann cutting amplifier. We went internal to the Neumann rack and bypassed all the tracing simulator circuitry; there was a great big delay circuit in it to decide whether or not it would shut down. It was a safety feature and we bypassed that, injecting the signal directly into the RIAA network. Star Wars was the first one that was cut with that configuration. Sonically, it was a huge step forward from the other stuff. That's MFSL 008.

By the way, that box that John Meyer built for me, and which now lives in this rack out here, is the amplifier that is the line driver box for the woofer amplifiers. The little box with the gain control, polarity reversal, each channel separate, and the meters on it. It's about 10 hertz to about 100 kilohertz band pass. It was designed by John Curl and John Meyer, and it's a one-off, hand-built job that really works.

The Development of the UHQR

Dave: Another big advancement at JVC was UHQR (Ultra High Quality Recording). You insisted in the development of that.

Stan: Well, I wanted a record that was about as thick as a 78 to help it maintain its mechanical stiffness, because we didn't use record changers anymore. There were two reasons for having the label ramp and the groove guard on a record. One of them was that if you take the record and hold it as if you're viewing it from the edge of the turntable, edgewise, and slice it from left to right, right through the center hole, and then stand it on end, it's a modified I-beam. The center section where the modulations are is very thin and flexible. At the edge there is an expansion into what we call the groove guard, and in the center there is an expansion into what we call the label ramp. The first reason to have this was for the pressing people to save vinyl, because the part where the modulations are, which is most of the record, could be very, very thin, sometimes like ten-thousandths, fifteen-thousandths thick and that's all. The other reason for having the label ramp and groove guard is that in the days when we used to stack records on record changers, the label ramp and the groove guard would provide the record's rotational drive. The edges touch, the label ramps all touch, but the modulation areas in between are all separated, and the record is still driven nonslip by this format.

Dave: So the reason this is called a groove guard is that it kept the grooved areas separated.

Stan: Sure. None of the modulation areas touch. They're separated by several thousandths of air when you put four or five records stacked up. It's a rather ingenious way of saving vinyl and saving modulation areas as well. But when we got into audiophile stuff, nobody in his or her right mind would have a changer. Then, by God, let's make a record that's thick enough to have some substance to it, the concept of a flat record, no groove guard, no label ramp, so that there would be the minimum possible stresses within the record when it's pressed.

When you look at a lacquer, it’s optically flat. When you master a wide range of dynamic music on this lacquer and then look at it in a good, straight-line light source such as the sun, you see that the surface where the land is, still is optically flat, but when you press the record from that, where the heavy modulations were, the record isn't optically flat. It has a dimpling effect that looks a lot like orange peel or bad paint on a car. Literally like the skin of an orange, pockmarked, and this creates a lot of subtle background low-level roaring and just extraneous noise in the music that wasn't there originally, and wouldn't be there if you had played the lacquer from which the pressing was made. If you look at normal stampers, which are typically 0.007 thick, and you, look at stampers that have areas of high-level modulation, you can see the modulation activity from the back side of the stamper. Now, when you put this stamper on a record die, which is a hydraulic ram that's got a mirror-smooth surface, and you press a record, all the deformities on the back side of the stamper come right through and so you get this dimpled effect. I talked to the Japanese fellows about this and they said, "How can we get rid of that? How can we make so that when you look at the back side of the stamper you have no idea what the modulations are? No clue as to what the modulations are on the other side. I don't want any visual or metallurgical dissimilarities." So we could make the stampers a bit thicker and we can laser trim them. Ah so.

And that's what they did, laser trimmed those back sides, and they're just as smooth and flat as they can be. RTI, kind of borrowing on that concept, applies a centerless sander to the back sides of the stampers. The stampers are like, so big (about 13 inches in diameter), and the sander has two of these five-and-a half-inch size disks with very fine grit that achieve virtually the same thing. You almost never see any of this dimpling stuff on these RTI records, especially the 180 gram ones. That was one of the major hurdles to overcome. I wanted this record to be good enough that I could look at the surface and say, "This looks like a lacquer." I didn't want to see any difference, and knew if I couldn't see any difference, I probably wasn't gonna hear any. You could be guaranteed that if you could see a difference, you had to hear a difference. I mean, one cannot be there without the other following. So, after they got that back-side problem smoothed out, boy, I tell you what, those UHQR's are super. I asked them why couldn’t we do that with our regular records? "Ah so, too expensive." I agree. And the regular JVC records were very good indeed.

Big Titles and Killer Disks

Dave: So during those years you were with JVC, you cut for Crystal Clear, you cut all the Telarcs, you cut all the Reference Recordings, until Paul Stubblebine started up.

Stan: I started by cutting Tam's first thing that he did for Reference Recordings. The first thing I cut for him I believe was called Kotekan or something like that. Tam'll tell you the exact name of it. It was basically a random-phase concerto for nine bass drums (laughs). Also, the tape was recorded on a Nagra machine for which we didn’t have the right playback EQ, so we had to just experiment with AES and CCIR EQ 'til we got what worked. It was a real bugger to cut. We had a helluva time with that. I think it was after that Tam did this interview that you were showing me here (The Absolute Sound, Vol. 4, No. 14). Because at that time I didn't know of Tam.

Dave: You were cutting something for him during that interview in 1979, as a matter of fact. There's a sidebar in there saying that he had come to you with something to cut and had done the interview at the same time.

Stan: I cut David Wilson's recordings. Remember his organ record, Recital (Wilson Audio W-278)?

Dave: Sure. That's a fantastic recording. I love it. And it's surely right up your alley.

Stan: Yeah, yeah. It's a very nice recording and as I recall, it's one where I was totally bowled over because I think that David recorded it with AKGs (C-414Es) in figure-eight configuration, and it really surprised me because I didn't think there'd be any bass. And there was lots of bass (laughs). Yeah, that was one of my happier moments. I think that was when I first met Dave Wilson, when he brought that tape.

We did the Cleveland Winds with Freddie Fennell. That was quite an experience. The first one I did, of course, was on Telarc, and that's when we first got it right with the bass drum in the back center of the hall with the drum head facing outboard. I was at the recording sessions for that. We played this Gustav Holst suite, Number One in E flat. The third movement starts off with a little bit of a fast passage in the upper woodwinds, and brass followed by a triple forte slam on the bass drum that defied all description.

Dave: A real kerwhapper, in your parlance.

Stan: Yeah, it was a real kerwhapper, all right. Freddie had brought his own bass drum beater with which to whack it. He had told me that he had gone into an old furniture store and found a four-poster bed and bought the bed just to get the posts off of it. And the bass drum beater was one of these bed posters with one of these eggs on the end of it, you know, and he'd shrunk like a chamois around it. So with a slightly-leather-covered wooden beater, he went back there and wham! It really made a helluva bang. I remember that we played a test pressing of it for the 1979 AES Convention or something, and then Kenny Kreisel had just started up his woofer company called M&K. I remember I had a test pressing of this thing from RTI, so we took it in there and we played it on Kenny's system. It started out rather quietly and then it built up to the horrendous swat! I told Kenny, "You'd better not crank it up too high because it's got a helluva loud bass drum on it." And I remember Kenny's words, "Ah, our woofers'll handle anything." I bet he'd probably prefer I didn't mention this, but then here comes this music, pretty loud already, ya know, and it's pretty well filling the room, and here comes this big swat! on this bass drum. And I think it deconed all four of his woofers simultaneously. I said, "I'm sorry, Kenny. I tried to warn ya."

But it's like those big excursions on that 1812 Overture, the cannon shots. I remember Steve Temmer of Gotham Audio called me up when he looked at these huge excursions under the microscope and he said, "You can't do that with a Neumann cutter head. And I said, "Well, I'm sorry, Steve, but I did do that" (laughs). He said, "But a Neumann cutter head won't excursion that far." I said, "But it did. This cutter head and cutter system that you sold to JVC, it's the one that did that." He was really hard pressed to believe that. He could not understand how we got such a huge, I don't know, 455 microns, no... it was big. And you could see it with not only the naked eye, but with the half-blind eye. I can see it without my glasses, you know. And the bass drum on that first Cleveland Winds record was very similar to that. In order to cut either one of those, the only way was to cut seventy lines per inch in order to take care of that wide of an excursion. There was an "Expand" button on the lathe that you could push just after a cut or something that was real loud so that you wouldn't get groove echo. You could push this thing to spread the grooves out a little bit more. I ran preview drive up all the way, I pushed Expand all the way, and I ran the pitch drive selector clear over as coarse as it would go, in order to accommodate these. It was like the same spiral rate as doing a spread. And you could see the feed screw going around like this to accommodate those big modulations.

Dave: So you were pushing the envelope, but not quite breaking it.

Stan: Yeah (laughs). That envelope was more like a trash bag (laughs).

Dave: That cannon shot's probably still the most famous killer disk of all time.

Stan: Right. And it turned out to be just right. We made a lot of test cuts to try to get that level just right, and we were checking it on that JVC turntable with that Denon moving magnet cartridge. We made one test cut and we could always play it, and we made another test cut and we could play it part of the time, and then we'd increase the level about one dB more and then could never track it so we backed the level down. Jack and Bob told me that with those records, fifty percent of the people could play them and fifty percent of the people bitched because they couldn't track 'em. It was such a challenge for them to try to track these things. Finally, when those stampers wore out, and they made so many stampers from so many mothers, and the mothers were worn out and the recording had to be remastered, Bruce Leek remastered it on this lathe when it was at IAM in Orange County, otherwise known as the Sound Dome. IAM was International Automated Media. So Bruce cut it, and he cut it at just a little less level and then everybody was disappointed because they could all play it. Later, Bruce cut it again, 'cause he said, "By God, I can do better than that." So he jacked it up two notches and then nobody could play it! So there's three versions of that 1812 Overture out there, two which Bruce cut and one which I cut (laughs), but you make test cuttings and you try real hard to get it right the first time, you see.

Dave: So by loaning out the third version of that you can astound your friends and confound your enemies by giving them one they can't track.

Stan: Oh yes, absolutely. "Betcha can't play this one, kid" (laughs).

Technical Topics

Absolute Polarity

Dave: The very first thing we did today when I arrived at your place was to listen for absolute polarity and do a little demo of that.

Stan: With one of Jan-Eric Persson's recordings. We played "Nobody's Blues But Mine," and we played "Black Beauty." These are from Thomas Ornberg's Blue Five, Opus 3, No. 9102 and Opus 3, No.8003, respectively. And the sonic differences there are very evident when flipping the absolute polarity switch on the Parasound D2000 D-A converter.

Dave: You could quite clearly hear the difference. Your favorite test of absolute polarity is trumpet, correct?

Stan: It’s certainly, for me, the easiest; any instrument that produces a saw tooth or highly non-symmetrical waveform will work. The trumpet (or trombone) is so easy because your hearing acuity is highest in the midband, which is where these sounds live. I remember one time helping a friend of mine here in town. Tommy Pearl has a band called The Burners, and it's basically like a Chicago group. It's a rock band with brass (trombones and trumpets) and saxophones. Tommy plays very good trumpet. He had this sound system that was really quite good, and I remember one time I was helping him get set up at the Officer's Club, and he was playing his trumpet. Every time he played his solo into one particular mic (pinching his nose) "it just sounded like this." He was having the guys run around backstage, trying things with EQ and gain structure and everything else, and he couldn't get that really bad sound out. He took a break and came down to where I was sitting, and I said, "Tommy, I think you've got a polarity inversion in that one cable," and he said, "Yeah, 'ya think so? Would that make a difference?" I said, "Yeah, you can you blow on your trumpet, and the wave form is a saw tooth wave. You've got almost nothing here on the zero volts line and then you've got these big spikes that go up, but they don't go down below the zero line. They just look like the dorsal fins on a dinosaur, 'ya know."

"Now," I said to Tommy, "if you can imagine yourself suckin' on your trumpet to produce the polarity inversion of that, the negative going, that's what coming out of the loudspeaker" (pinching his nose again). "It sounded really bad!" So he put in another cable and, "Wow-wee." It was there, just, 'ya know, like Clark Johnsen'd say, "the difference between night and day." And it was, it absolutely was. It's something that literally everybody in that band was able to hear, and they were behind the loudspeaker system! Because the loudspeaker system was along the front of the stage and they were all behind it, they were only hearin' the back side radiation, and they could still hear the difference!

Dave: Interesting, interesting. I know that at the last two Sapphire Club meetings I've been to, at your kind invitation, it seems like everyone recognizes the value of absolute polarity. That should warm Clark's heart. We could see that on your oscilloscope here, too.

Stan: Right, right. And I'm going to bring my string bass in here (the cutting room) and set it up. It's got a pickup on it, which I can plug into the system, and you can see the effect of downbow/upbow really, really easily, and if you can see it, you can hear it. So we can record some of it on the Panasonic SV-3800 DAT recorder and then play it back without the effect of having the bass fiddle in the room.

Dave: You were talking earlier about piano recording and absolute polarity, and how that ought to be done.

Stan: Piano is a peculiar instrument, in that if you look at the way the hammers attack the strings, the hammers come from in front if it’s an upright or spinet-type instrument. They attack from the viewpoint of the performer or the observer. They hit the strings, causing them to depart from the listener. The string's first shock wave going at the sound board is in the same direction, so when you look at the spikes on a piano that have been recorded with microphones from in front of the instrument (at the player’s location), you see a lot of negative-going energy. That's what we saw in that one recording of the Ornberg Five from Opus 3, where after we reversed the absolute polarity, all the other instruments were positive-going polarity, but when the piano did its solo, we saw negative-going polarity. Now, if the microphone had been placed, if it's an upright piano, at what we normally call the back side of the instrument, all that would've been changed. Just turning the piano around 180 degrees or miking from the back side would've alleviated that kind of problem. Some folks would think that it's a minor thing, but it's one of those things that, taken in totality with a whole bunch of other things, can make the difference between really feeling like you're there and feeling like, I'm there but there's somethin' a little not quite right about this. Concerning grand piano sound, the polarity goes the other (+) way because the hammers strike the strings from underneath, displacing strings and soundboard upward, presumably toward the mic diaphragm, giving positive polarity at the output of a properly wired mic. And that gets us into this positive polarity situation that I was talking to you about on the string bass, where the down bow and the up bow are of reverse polarity from one another, which can clearly be seen on the oscilloscope.

One of the things that the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy was famous for was the broad, rich string sound. Ormandy encouraged random bowing in his string sections, especially on recording sessions, because he knew that a down bow sounded different from an up bow. This is why, when you want to accent a note, the composer/arranger writes it for a down bow. If he wants three accented notes, he'll write three successive down bows. Not down, up, down. They sound different. They are different. Not that the musicians understand too much about the polarity of the output, but their ears tell em, "Yeah, there's a difference in sound. I don't know why, but there's a difference in sound and the down bow sound is what I want here." If they want something quieter, like a quiet entrance to something, they'll almost always specify an up bow. If they want something to enter gracefully, its an up bow. It's an inverted polarity.

Cutter Heads

Dave: One of the questions Raymond Chowkwanyun wanted me to ask you was whether you prefer Westrex or European cutting heads.

Stan: One of the things that I've always been impressed about with Westrex cutter heads is that their bass sounds so good. It really does. Now, let's face it, a Westrex is a big-ass machine. I mean, hell, it's got a huge magnet structure. That’s a very, very healthy magnet structure, and it was a basically a medium-impedance, 16-ohm type thing, designed to be driven by tube amplifiers, and it had very good conversion efficiency. So the old Westrex systems were driven by their tube Westrex 70-watt-per-channel amplifiers. Hell, they were very good sounding systems. Where they didn't do so well was in the real high frequency stuff because it’s difficult to accelerate such a large moving mass. Again, with that RIAA equalization, it didn't take much to cause them to go "bad news". The amplifiers and the RIAA networks weren't as stable in those days as they are nowadays. But boy, I tell ya, what good sounds Bernie Grundman cuts with his Haeco cutters, which are, basically, modified Westrexes! They're large-mass devices, and they work very well.

We need to talk about Haeco for a moment. Holzer Audio Engineering Co. Howard Holzer was as near genius as anyone in the earlier days of microgroove recording. He had great ears, and knew the theory and creative, practical application of electro-physics probably better than any other engineer alive during his time. He was the engineering brains behind the original Audiophile Records that began as microgroove 78 rpm 12-inch cuts with unbelievable dynamic range. They were pressed on clear red vinyl and had gold labels and sounded as good as they looked! When Howard came to trust 33 1/3 rpm enough, his first releases were microgroove 33 1/3 16-inch cuts; Howard knew the value of high scanning velocity on playback; this was long before the advent of elliptical styli and all that stuff. Look at your early Contemporary jazz recordings; "Engineered by Howard Holzer and Roy DuNann." These guys put A&M Records on the air, which is where Bernie Grundman honed his considerable mastering skills for many years. Howard was also an excellent pilot, and spent a lot of time in Mexico trying to help the local folks get their recording technology up to snuff. Howard Holzer was taken from us way too early when both of his engines failed on takeoff due to contaminated fuel.

All those products that Bernie’s cut for Classic Records, and whatnot, geez, they sound excellent, you know. Some people talk about "a top-end something" to his classical cuttings. Hell, I don't know, that may be the sonic flavor of his console. It may have nothing to do with his cutter system per se. It may be the sonic signatures of the mics and pre-amps in the early recordings. I don't know, but I'll tell you what, if I could cut a record that sounds as good as what Bernie cuts, I'd be very, very proud of it. And it doesn't matter to me whether he's using Haeco, Westrex, Ortofon, Neumann, John Deere Barbed-Wire Fence, or anything else.

On the other hand, these Neumanns have small magnet structures, and the drive coils are low impedance (4.6 ohms), so you have to drive 'em with a low source impedance, high-current solid state amplifier in order to get really, really tight bass. You try to drive this cutter head with a tube amplifier and you're asking for bass, which is, when you listen to it, hard to decide, "What's the guy doin' on his instrument, anyway," 'ya know? Is he just playing or what? The only tube Neumann systems that have been successful, that I’m aware of, are the systems at The Mastering Lab, where the amps were designed and built by Sherwood Sax, brother of Doug Sax, the owner/user of these great systems.

Concerning bass sound, in the early days of stereo recording, many recordings that Howard Holzer, Lester Koenig, Rudy Van Gelder, and others made of the early jazz, had a lot of bass players playing Kay basses, Kay being a brand of instrument. Kay made Harmony guitars and they also made cellos. All these basses (and other instruments) were plywood, and they had not very good sonic attributes! I have one of those basses in the house. It’s the blonde one, the same model as the bass seen in the early Elvis film clips. You can listen to the difference between it and my five-string bass that's maple and spruce, and you'll hear an instantaneous difference. Most, if not all of these bass players were using the Kay basses with gut strings. (That was the only type of string to be had, in those days!) Nowadays, almost nobody uses gut strings. I want to say "nobody," but I know there's somebody out there that does, especially in the Baroque and Classical field. In the small orchestral groups, where there is a big push for "original instrumentation," there are a number of people who use gut strings for Corelli Concerto Grossi and things like that. For jazz, I think almost nobody uses gut strings anymore, but there they were. When you listen to a lot of that off of a Neumann cutter head driven by a tube amplifier, you don't know for sure what the bass player's doing, or doing it with. The sound’s too loose and nebulous in that frequency range due to lack of good servo mechanics to really be able to tell for sure.

That doesn't really answer the gentleman's question about which head I prefer. I've got a recording of Les Elgart's band in stereo on Columbia that is just so clean and crisp and clear. I know that it was recorded with a Westrex, as looking through the microscope reveals some really minor advance-ball scoring on the original lacquer. (See advance-ball discussion in the section on Bernie’s setup, near the end of the interview.) The recording was definitely mastered on a Scully lathe. I can tell that’s so by looking at, and listening to the lead out and the tie-off groove, and those clues tell me that was done on a Scully. So far as I know, in those days everything Columbia did was cut on Scully lathes with Westrex cutter heads. So we can listen to it later and hear it's just neat, super sound. Hell, maybe somebody snuck an Ortofon in there, I don't know. Or maybe somebody decided (it's cut at a rather low level), maybe it could be that an engineer with ears said, "You know, maybe if I cut this at a low enough level I can take all these Fairchild limiters and chuck 'em out, and take these low frequency crossovers and get rid of 'em, and I can, if I’m really careful, I can make a record that sounds really great! That just might've happened, ‘cause every once in a while you could get some awfully magnificent stuff out of a Westrex system, if you just treated it right.

Why 180 Grams

Dave: How did 180 grams come to be kind of a magical number for LPs? It must be a compromise between something and something else.

Stan: Well, yes, talking about the 180, I recall chatting with Rick Hashimoto at Record Technology. When the heavy-record thing first started, it was done by JVC, when we came up with the 200-gram UHQR. That was, hell, it coulda been 205, coulda been 210, or whatever, but it was 200 grams, and it was really the finest phonograph record ever produced. I know that RTI had tried various thicknesses, and that 180 is a good compromise between heft and solidarity on the one hand and econoline regular on the other, but there's virtually no difference in sonics between a 180 and a 200 (using the same vinyl compound). There's more difference in sonics between whether you use Keysor vinyl or whether you use RimTech vinyl, or what percentage of regrind you may use as opposed to so-called "pure" virgin vinyl

Dave: What is regrind?

Stan: When a record is pressed, you purposefully put too much vinyl in the press, to make sure all the grooves are filled and all the gasses carried out. So it's like a waffle iron that’s overfilled and when you put the two halves together, the extra stuff comes out the edges. The extra stuff (vinyl) is trimmed off with rotary trimmers, rotary shears, and the trimmings fall into a big drum. Then it's collected in one place and chopped up and cleaned and vacuumed to get dirt and impurities out of it. It also is brought through a magnetic field to make sure that any metallic particles that might be in there are also removed. Then the stuff is ground up into the same size particles as the original, which look like mouse turds. It's about that size. Then the regrind is all blended together with virgin material and the mixture goes through the machinery, where it's heated, blended, and extruded at some 300-odd degrees, becomes another "patty," and starts its life over again.

A lot of pressing-people don't like to talk about regrind or admit to its use, but re-cycling overage is an economic as well as environmental reality. Regrind vinyl has already had a lot of the volatiles cooked out of it during its first go-around through the press, so by definition, it's stiffer than virgin material. It therefore has better (or at least different) high frequency playback characteristics than does virgin vinyl. I encourage people, when they want to make a record that's got a lot of snap or bang to it, as in DJ dance-club music, to get as high a percentage of regrind in the vinyl as they can get, consistent with the quality that they want.

Dave: What's your opinion of the dehorning of masters?

Stan: Well, I don't know of anybody who does that anymore. It seems to have been fairly popular in the sixties or seventies or whenever. A cutter stylus cuts and it also plows. With a snow plow you go down the road and you pile up all this humongous crap along the curbs and sidewalks. Well, you hope you don't get much of that when you cut. Cutter styluses are manufactured much better nowadays than, shall we say, thirty years ago. The burnishing facets weren't so accurate then. Sometimes you got a nice cut in the groove but then sometimes you didn’t, and there might be a bunch of stuff stacked up at the edge of the groove. That stuff was rough-textured and made separation of the lacquer master from the first metal plating very difficult, because the stuff that's thrown off, when viewed under a microscope, looks like a string of cinders. It's porous, like a sponge, you see. So when you're electroplating that stuff, well, the metal molecules get inside and you can imagine metallic nickel getting inside a sponge and then how do you peel a sponge off that electroplating? You're left with little bits of stuff stuck to the metal (NOISY!). So the idea was to knock off those. It affects the sound. I don't know anybody who does dehorning anymore. At least I don't know anybody that's involved in high quality work who does it, mostly because there’s no need for it with today’s better styli.

DMM

Dave: Stan, what's your opinion of direct metal mastering?

Stan: I've heard some really good stuff for string quartets and vocal, stuff that doesn't involve bass (low end), but I haven't heard things that sounded really good on the low end with DMM. The cutter head is small and you have, I think, just the physics of trying to push the cutter stylus through copper instead of lacquer. I don't know how thick the copper plating is, but I also don't see much random-phase stuff in the bass on DMM, whereas with lacquer you can get a vertical modulation of 7 mil. In other words, the lacquer coating on the aluminum substrate is thick enough (15 mil) to handle the 7 mil modulation vertically. If you have modulation that's vertical, it will be so inherently non-linear on the down stroke. Well, maybe they predistort it, depending on the depth, but as I say, I've heard some stuff with midrange and top end, like string quartets, that sounded pretty darn good, but I haven't heard anything that I felt, "Well, that's better than anything that coulda been done on lacquer."

I can look at a pressing and can tell you right away if it was done DMM or lacquer. The pressing reflects light differently, depending on the method of cutting. When you cut a DMM, the delineation between the 45-degree groove walls and the flat surface of the land, that angle is very clearly defined. On a product that's been DMM'd, the final pressing comes out looking like the original cutting, as it should. Now with very good electroplating on a lacquer, you'll see it almost the same way, but if even just a little too much heat is generated during the preplating, either through too much voltage, therefore too much current, flowing in just the one or two micron levels of thickness of silver that's on the lacquer before the nickel builds up, or if the plating tank itself is too hot, then there's a rounding of the corners where the groove wall meets the land, which is easily discernible to the semi-naked eye, provided it's a trained eye. I can see it easily. All I have to have is a reasonable source of light and a good pair of glasses. I can tell you right off the bat, and by looking at that I can also tell you this product isn't gonna have much high frequency response, either. The more rounding you see, of where the groove wall transitions to the land, the more rounding of the high-frequency modulations will occur on the groove-walls themselves, therefore the less high frequency response. Every jagged little etching in the groove, on the groove walls, is going to be rounded a proportional amount, just like that. And it's worse at the inside diameters because not only is it a slower linear speed which produces progressively shorter wavelengths, but in terms of this plating, the center post is the electrode, so all the electron flow from the outside edge, and everywhere in between, goes to the center, you see. The current density, and therefore the heat, is higher at inside diameters.

So my opinion of DMM is that it's very interesting, indeed. There’s also a high-frequency bias applied to the cutter to eliminate stylus chatter at low cutting levels. As I say, some program material is very well suited for it. I know it would be especially good if you had choral works or string quartets and had a long time on the side. The DMM process is immune to the groove echo problems of lacquer because the copper isn’t affected by the cut-and-plow stress-relief phenomena that plague lacquers in a warm plating environment. However, all the killer LPs I've ever heard have been made off of plain old nitrocellulose (laughs).

Dave: I've heard that you took the nitrocellulose shavings that came off the lacquers in MoFi and took them out in the parking lot.

Stan: Occasionally so! You can light 'em off and make a good boomer out of 'em. That's one reason, by the way, indirectly speaking, why this lathe is almost in the middle of the room, because in every mastering facility I've ever worked in, the lathe is smack-dab against the wall. You couldn't get around to service it from the other side (to empty the chip jar or replace belts). Also, near the walls is where the most bass is. So you have the most possibility of contaminating the sound on the disk through airborne low-frequency vibrations from the loudspeakers. But the most important reason is that you can just walk back here and work on this thing, you know. We can look right here and see the pickle jar with the thread in it, the shavings, what we call the "chip," or what the English call the "swarf." That's a great old German pickle jar, bunch of explosive stuff in it. Cellulose. To go boom, you wad it up in a ball, put it out in the driveway, and light it up. Thhhumppp! Sounds just like you lit off a little toy rocket or something. And then it leaves about a million little tiny black goobers hanging in mid-air!

VTA Test Record

Dave: Something that Michael Fremer mentioned in one of his recent articles was that you once had a concept for a VTA test record.

Stan: Yeah, yeah. We can take musical signal, which I really think is the best, or you can take pink noise, and sum it to mono, reverse the polarity in one channel, and cut it vertically. A whole lot of people don't have stereo/mono switches on their preamps or whatever, which is a travesty because if you're listening to a mono record, you really must have a mono combining switch for two very specific reasons. Number one is that there's a lot of vertical nonsense (like "orange-peel" (mold-grain), vertical rumble from ball bearings in mono lathes, and long-wavelength displacements due to warpage) happening on the surface of the record that has nothing to do with the recorded signal. You’d like to get rid of those vertical disturbances that are using excessive power and polluting the music. But even more important is that arm resonances are excited. The resonances on different axes are of different frequencies, because most arms are not purely symmetrical. This one isn't. (It's a Grace 16" model 707, by the way.) So it has a curve near the cartridge end, and slightly curved at the pivot end, too. So it's gonna exhibit more stiffness in one plane than it does in another plane, and therefore a differing set of resonances in each. So when you play a mono record, and some guy's in there pluckin' the bass, and you play it back in stereo mode and look at the oscilloscope, you see all kinds of ovals and everything else happening in the bass, whereas the bass was recorded mono, but the arm vibrations, the vibration modes are causing spurious vibrations in different planes. So sometimes one note will come out loud on one channel and another note will come out loud on the other channel, depending on the particular notes being played, when you're in stereo. When you're in mono, you combine these differences and the arm resonances are not eliminated, but they're made common mode. That which had appeared as pure vertical resonance is eliminated. (Tympani that "move around" backstage when playing different notes can be traced to this different-resonances-in-different-planes phenomenon.)

Now, if you did this with a test record where you had mono pink noise or mono music, hell, that'd be great. You make sure, first of all, that obviously the cartridge guts are oriented horizontally, azimuth-wise (level). Many times you’ll find the output of the two halves of the cartridge aren't equal, almost never are. You gotta get the cartridge lateral first, then get the levels equal, then combine to mono, then reverse the polarity of one channel only. You gotta do 'em in the proper sequence, I mean, otherwise, once you combined 'em to mono you don't know which one of those two channels is actually puttin' out more or less than the other. So you have to get it zeroed out in the stereo mode first, then combine it to mono, then reverse the polarity of one of those combined channels, and then on this hypothetical test record, you'd vary your vertical tracking angle to get rid of the most sound, in effect, cause the most cancellation.

Dave: That might be something that would sell. A lot of people might have an interest in that.

Stan: Yeah. We were talkin' one time about cuttin' a test lacquer at different locations: cut somethin' here, cut somethin' over in AcousTech, cut something at Doug Sax's, cut somethin' at Bernie's, just a minute or a minute and a half of some noise from all the different guys, mono, vertical modulation, on one lacquer. Then on the other side, same kinda thing from the East Coast. However, I don't know if I want to send a lacquer to the East Coast and have it cut and then have it sent back here and try to have it processed. You'll lose so much, time is against you. Temperature variations are against you, especially heat, but that'd be kinda neat if we could do that.

Yeah, I think that all Neumann things, provided they're set up according to the regular Neumann mechanical alignment procedures, are gonna be the same. But now, Bernie's is gonna be different. Doug Sax’s rig at his Mastering Lab will be different as he has a Neumann cutter on a Scully lathe. Len Horowitz' Scully's gonna be different and MoFi's gonna be different. MoFi has a Neumann lathe with an Ortofon cutter head, so it’s different from the others, and I don't know which difference it is. I don't know if it has a greater or lesser cutting angle than these other heads do. They're supposed to be fifteen degrees, but I don't think they're actually that much. I think they're maybe seven or eight degrees.

Dave: Really? That's interesting. Quite a difference.

NAB vs CCIR & Tape Handling

Dave: Stan, how you feel about NAB vs. CCIR?

Stan: Well, I think that NAB is a mistake that never should have happened, but it did, so we have to live with it. CCIR or IEC, as they call it nowadays, is a recording characteristic that I really like because in the midbass and bottom end it doesn't do anything: no EQ at all. Leaves it alone, and there is just is a 35-microsecond time rise above 1000 cycles. By the way, 30 ips is just half of that, just 17 1/2 microseconds time rise. So you could take 30 ips tape, if you want to master at half speed, just play it back 15 ips on CCIR, after shifting the "knee" of the curve down an octave. It works out quite well. But NAB bass-boost EQ has been the cause of a lot of tape saturation in the bass, things like that. Some of the folks that talk about the soft, fat bass on analog tape are relying on the non-linear saturation characteristics to get that effect, often without being aware of it.

Dave: Do you have a favorite brand of tape?

Stan: Well, of the things that have lasted best over the years, the old Scotch 111 has far and away consistently sounded the best, but there are no lubrication properties at all in that tape. It's like carborundum paper on your heads, but God, it retains its signal and sounds very good over many years. And that German Agfa, it's pink on the back side, PER 535, I think the number is. Kind of a grayish-brown oxide. And I always liked the Scotch 202. It would track better through the guides and the head stack because it wasn't glossy on the back side, and was made of mylar. It was matte finish, so the capstan would grip the tape better. Both those tapes kept their high frequency response well. The tape that Keith O. Johnson used to do his analog recordings for Reference Recordings was TDK, which was also of a large magnetic particle design, very much like the other tapes I've mentioned. It really retains its signal well, with very little print-through and very little high-frequency smear, but that stuff hasn't been in production for a number of years. So, other than my experiences with those, I don't have a lot of good firsthand experience with recording tapes. If I see certain Ampex tapes, like the 407 or the stuff in that era, 406, 407, I get a little nervous. This was in that time frame, around in the seventies, when we had trouble with the binder migrating to the outside edges of the tape. When you tried to play a tape back twenty years later, it was all glued together. Causes a nightmare trying to rewind it, clean it up and play it when you're re-releasing something from an archive. Takes too much time to clean it.

Dave: Was this after the ban on using whale oil as a lubricant, which I think, according to Doug Sax, happened in 1976?

Stan: Well, that's about right; ‘76 or ‘77. That was Sperm Whale oil. That stuff was one of the major ingredients of the early automatic transmission fluid for cars. Right around that time, when they quit using that stuff, the failure rate of automatic transmissions in cars in America went from about seven million a year to about seventeen million a year. There was a lot of anguish and a great gnashing of teeth, so to speak, over the loss of that supremely good lubricant. And I don't know that anything has ever come up that's been as good as that stuff. Best lube in Mother Nature’s arsenal!

Dave: You were saying earlier, too, that you don't really believe in baking tapes, or find that there's much advantage in baking tapes.

Stan: I have not found an advantage in baking tapes, although sometimes I think I must really be in the minority, or I don't have both oars in the water or something, maybe I wasn't issued both oars. The experience I've had with tapes at Mobile Fidelity was that we'd get a tape that would be really sticky and we'd say, "Well, we'll send it off to some place and get it baked," and well, it would come back and be just damn like it was when we sent it away. What a waste of time this was! I could have been cleaning it, you know. Clean it with Freon TF, pulling it between your fingers. Clean, lint-free rags, pads, get all that sticky stuff off. It takes forever to clean tape that way, but it works! 2400 feet through, one foot at a time, but you could play it thereafter and you couldn't do that after baking. We put it under vacuum, too, in a bell jar, and sucked the air out of it, in the hope that would do something. Didn't do anything that I’m aware of!

Dave: So, there's no substitute for tedious, careful cleaning by hand.