|

You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback ISSUE

18

Tracing Error 4 -

A book review

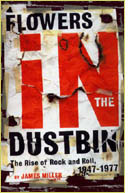

Flowers in the Dustbin: The Rise of Rock and Roll, 1947-1977 by James Miller. Simon and Schuster (1999), 416 pp. It will come as no surprise to the alert reader of Flowers in the Dustbin when, at the conclusion of 354 pages of self-described "sophisticated disdain," author James Miller admits that rock is not his favorite form of music. A former rock critic with Newsweek, Miller tells us he left the rock biz two years after an epiphany revealed to him that rock had been corrosive to American musical culture. But why did he return with this book? For in Flowers in the Dustbin, Miller displays an understanding of history, culture, and art that is not so sophisticated as you might expect from a New School professor and author of tomes on Foucault and Rousseau (as the overleaf tells us). Rather, Flowers in the Dustbin offers rock history as told by industry hacks, bragging about the success of their own hackness, elevating themselves and their machinations over the worthless commodity they sold: rock and roll. Miller takes self-serving industry cynicism at face value, adds an abrasive would-be intellectual sneer, and in so doing becomes a hack's hack. Miller's simple guiding question, essentially why rock became so popular, has an equally simple answer. To Miller, rock refined music down to its essence, a big beat and simple hooks, and then packaged itself for youth consumption in an era when youth became culturally dominant due to demographics. To Miller, rock is inescapably intertwined with youth, and not necessarily in a good way. Moreover, because he cannot seem to extricate rock from his own youth, he will not allow that rock can be a mature art form.

It seems to me all good music offers surprise, a chord or a melody or a beat or a sound that sticks out—that's what makes it distinctive and interesting, what engages us. While there are some mediocre talents able to put it all together for a worthwhile song or three, the enduring music, the stuff we listen to over and over through our lives, is a lot more than just occasional serendipity. I hope all of our readers listen to rock music that contains subtle creativity and seasoned craftsmanship, and some which is also coarse and full of sound and fury in a subtly creative and well-crafted way. As for mature forms of jazz, blues, country, and gospel, I suspect most of us prefer to listen to the "coarse" trailblazers. And just how much craft (as Miller deploys it) is there in Charlie Patton or Hank Williams or Armstrong's Hot Fives and Sevens? Clearly these were artists that knew what they wanted, but their music was characteristically coarse, and thank god for that. How ironic that a critic who wrote about mainstream rock through the 1970s and 1980s, when it became a producer's medium, one of craft rather than inspiration, would complain that the genre didn't mature into a medium of craftsmanship. Miller's got it back-assward. Rock music became boring precisely when the craft of producers and session musicians wrested major label rock away from the gritty creativity of vernacular musicians. At the culmination of that process, in the 1980s, almost all the good music (and with it plenty of bad, to be sure) was to be found in the underground, and most pop music was bad. "Not enough craft!" complains a critic at one of America's highest circulation periodicals during the age of Quincy Jones/Michael Jackson, Nile Rodgers/Madonna, Steve Lillywhite/U2, and slicked up Born in the USA Bruce. Whatever. How did rock lose the sound of surprise? Well, as Miller describes 1970 in the biz, "a new mood, a kind of inchoate malaise, settled over the rock scene. The Beatles had officially dissolved... Jimi... Janis... Morrison... overdoses... no rock act of similar power and panache had presented itself." What? In 1970, the Stooges in the US and Black Sabbath in the UK, not to mention a host of other hard rock bands from Led Zeppelin to Steppenwolf to Alice Cooper (and on and on) were in their prime, and the Sabbath, Stooges, Zep trinity clearly had all the power and panache a record label could want, while the very large second string of hard rock bands was also making good music and filling arenas (though many of their albums, run through the major-label production mill, suck ass, in part or in whole; you need bootlegs to hear just how rockin' some of these bands were). It was precisely critics like Miller and his Rolling Stone cohort, along with the A&R men, who didn't want music like that to succeed, since it and its fans appeared to be too "coarse and puerile," and since it didn't offer the promise of soft-left pop utopian revolution or an easy, fun high. Despite the labels' and critics' half-hearted attempts to market it, this music was quite popular both in sales and concert attendance, but what would have happened if class elitism had not intervened? The industry continued to denude pop of its rock elements, a process nearly completed by the time Nirvana hit big. Only since then has the industry seriously and without reservation attempted to market heavy rock music. What's more, Miller makes mystifying distinctions between amateur and professional, and musical and non-musical. Hence: "it seems to me Aretha Franklin and Dionne Warwick and Dusty Springfield all are greater musical artists than, say, Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones, or Jim Morrison of the Doors." What is it that makes a singer who doesn't even write her own material a better "musical" artist than Mick Jagger? I suppose you might say that these women are better musical instruments than Mick Jagger, but then again you might not. Jagger really gets a lot across with his singing, beyond which he wrote music (and lyrics) and contributed to the production of his band's records to boot. Miller's point seems intertwined with his feeling that rock is about "amateurs" feeling around in the dark until they find something that sounds good, which lacks, in his universe, compared to "professionals" feeling around until they find something that sounds good. So he just downplays talent and professionalism. Flowers in the Dustbin takes the form of a series of episodes which are vehicles for Miller's themes, told via back-story and context. I did learn some things, especially about the early period of rock'n'roll where my knowledge isn't so deep, but Miller's condescension basically poisons the whole book. Atlantic Records founder Ahmet Ertegun is portrayed as a mere cynic, looking for a simple recipe that would sell, without regard for the quality of the music. DJ Alan Freed's posturing as a wildman, not the records he played, is what Miller thinks sold his show. What's interesting to Miller about Doo Wop is that its first teen star, Frankie Lymon, was an experienced pimp and drug dealer. While Miller claims to be a cultural historian, he is really just a critic. Much of his book is based on industry-insider accounts, which he doesn't interrogate the way a historian must. To his credit, he does foreground economic forces, but only in superficial ways. He is sloppy when thinking about the relations between musical genre (i.e. rock) pop audience (i.e. the pop narcotic), and the industry which mediates the two. He also doesn't think very hard about how change occurs, instead offering mountaintop pronouncements about musical meaning. His views on race and hipness (copped from Mailer), and gender, etc. are all flat and stereotyped, offering little understanding. Thus, at the end of the book, when he blames rock for the decline of American vernacular music, he is wrong on three counts. First, he is blaming the homogenization of culture on "rock" instead of "capitalism" with its "culture industry" or "mass media". [Tangentially, he rejects the very music which recognizes and takes as its point of departure this homogenization, punk and post-punk, as being too "nihilistic," which besides being supremely ironic, isn't even true.] Second, the "diverse forms" of American popular music from 1927 to 1957 that he trumpets as an alternative aren't quite as diverse as he claims—mainly they comprise a few takes on the blues and syncopation and a few takes on the ballad form. Seen in such a light, current vernacular music, from house and IDM and trip-hop to hip hop and r&b to hard rock, alt rock, twee pop, punk and hardcore and emo, stoner and speed metal and post-Sonic Youth rave ups seem quite diverse. It's pretty hard to argue there is a greater musical distance from Bessie Smith to Jimmy Rogers to Jerome Kern than from Toni Braxton to Slayer to Sigur Ros. Third, the pre-war musical jambalaya Miller lauds is a mirage. In that era, music scenes were highly regional, only sporadically accessible nationwide. That's why people like Alan Lomax and John Hammond had to go beat the bushes to find talent. That's why when a regional band like King Oliver's showed up in Chicago in 1923, or Basie's in New York in 1938, their music was received as such a revelation. That's why places like the Mississippi Delta and Memphis had such distinctive sounds—because you had to be there (or within the radio broadcast radius) to hear it. Today, the New School-appointed professor can sit in a New York apartment with a plenitude of reissues of pre-war music, representing thousands of heavy shellac 78s from Cincinnati to LA in just a few feet of jewel boxed shelf space, but Miller projects that postmodern condition into an ahistorical musical Eden. Perhaps the main problem is the gilded palace in which a mainstream critic lives. Miller liked rock'n'roll when it was a vernacular form, but he stopped listening to the vernacular version of it when it was driven underground by the industry which signed his checks. For every time Miller watched Bruce Springsteen from the VIP section at the Meadowlands, he missed the Minutemen playing in the East Village. If you like vernacular music, you must speak the vernacular—you must go into the small clubs and hear obscure indie records rather than just watching MTV and checking out an occasional buzz band. Ultimately, Miller's book betrays a self-loathing that is just damned unpleasant. Add to that a nasty cynicism, mediocre taste, and an utter misreading of history and you have a book that I can only recommend if you enjoy seething with rage.

|