|

You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback ISSUE

18

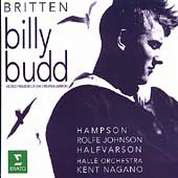

Britten - Billy Budd

Thomas Hampson (b), Billy Budd; Anthony Rolfe Johnson (t), Captain Vere; Eric Halfvarson (bs), Claggart; other soloists; Manchester Boys Choir; Hallé Orchestra and Choir/Kent Nagano Erato 3984-21631-2 (2 CDs). TT: 2:28:45. Operaphiles readily acknowledge the dramatic power of Billy Budd—it's hard to ignore a literary pedigree that takes in both Melville and E.M. Forster—but many are only dimly aware of the orchestra's distinctive contribution to this effect. Britten's use of the brass is particularly innovative: these instruments, besides combining for the fanfare-like perorations that the nautical setting naturally suggests, contribute individual strands to a pointillistic, ever-shifting texture reflecting the undercurrent of psychological ambivalence and duplicity. When I heard the piece at the Metropolitan some seasons back, the variety and brilliance of the sounds emerging from the pit were spellbinding. In this light, Kent Nagano seems perhaps not the ideal conductor for the piece. Whatever strengths Nagano brings to the twentieth-century repertoire, an instinctive feeling for orchestral color isn't among them. His recorded performances, with a variety of ensembles, are invariably neatly executed, but time and again, the sheer sensuous aspect of the instrumental sounds, the way they layer and combine into variegated textures, goes for naught. At the start, unfortunately, this performance lived up, or down, to my all-too-minimal expectations. The violin figures introducing the Prologue sound dry and none too confident—no sense of shape emerges, let alone any evocation of dimly remembered seascapes. The Hallé brasses are well-balanced, but each time they're about to break through to a climax, the conductor repeatedly pulls them back, producing a sort of musical coitus interruptus. Even the chorus, in the first act proper, sounds entirely too soft-grained and refined—perhaps meant to represent a scene filtered by memory, but more readily suggesting the Flying Dutchman's ghostly crew. Finally, the low brasses under the First Mate's speech in Act I cut through with sonorous depth—even Nagano can't entirely rein in a tuba descending to its lowest notes—and, with the dam of restraint thus broken, things improve considerably. The brass choir registers with good presence after the Sailing Master's monologue, and again before Claggart's. The low string "expansion" in Vere's quarters is vibrant, and track 11 and subsequent interludes finally capture the animated, pictorially undulating quality we know from the Peter Grimes interludes. There remain some unsatisfying moments—the solo saxophone's distinctive richness is suppressed, and the crescendos on the horn-and-bass chords in Act III sound consciously reined-in; for best appreciation of the scoring, I'd favor Hickox's Chandos album, despite an over resonant recording. But on the whole, Nagano's handling of the orchestra has a commendably strong profile. Turning to the singing—finally—Thomas Hampson is marvelous in the title role. His tone is unexpectedly, and properly, bright for the ingenuous Billy of the opening scenes, parcelling out his deeper colors later on to suggest Billy's sober reflections. His "half-asleep" responses to the Novice's baiting sound unaffected and natural. His enunciation is excellent, and his propensity for excessive artsiness—derived, to be sure, from his attention to detail - is, thankfully, mostly in abeyance; only the too-studied monologue at the start of Act IV loses the sense of "spoken" immediacy. Anthony Rolfe Johnson leaves a more equivocal impression. As the older Vere of the Prologue, he sings sensitively and comprehensibly, but in trying to color and "age" the voice he becomes tonally diffuse. Conversely, his thrusting, clear-toned Act I proclamation—I'll discuss this further in a bit—givess the impression that this captain isn't much older than his crew (which may not be entirely incorrect, after all). His best dramatic moments are the more restrained ones later on—his stunned quietude after Claggart's death, his chilling "I have no more to say" at the drumhead trial. In the third act's closing monologue, Rolfe Johnson at last rises to the stature of the role. Eric Halfvarson's "black bass" is well suited to Claggart, but his slow wobble is a trial and, combined with underarticulated consonants, renders him mostly incomprehensible in Act I. His enunciation improves for the Act II monologue, until the emotional temperature rises. Among the numerous smaller roles, Richard Van Allan contributes a vivid, characterful Dansker, and Christopher Maltman rings out clearly in the small role of Donald. The rest are more or less serviceable, projecting the text with varying gradations of middling success. This performance, by the way, opts for Britten's original four-act version of the opera, rather than his later, familiar two-act condensation. (As is frequently true in these cases, the performing edition is actually a hybrid, inasmuch as it retains Britten's revised orchestration.) The principal restorations are a stirring quarterdeck address in the first act for Captain Vere—ostensibly dropped because Peter Pears felt vocally underpowered for it—which builds to a brilliant choral finish, and some passages cut from Claggart's false denunciation of Billy in Act III. The former introduces Vere with a "heroic," rather than reflective, moment and makes for dramatic symmetry with the almost-mutiny in Act IV, and both scenes are worth hearing; but Erato sees this "world premiere" as a stronger selling point than I do. The recorded sound occasionally rises to excellence: the crisp percussion detail in the Prologue is breathtaking, and the changing sustained wind chords at the end of Act III come across with an organ like tonal and spatial effect. But Hampson's loudest notes at the end of Act II betray a hint of digital feedback, and the expertly crafted multiple chorus in Act III becomes aurally confused and coarse when the principals join in. The booklet includes an interview with Donald Mitchell and Philip Reed, editors of Britten's letters and diaries, and an essay by Mitchell; the libretto places track 15 on the second disc incorrectly.

|