|

You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback ISSUE

14

The Audio

Century, Part I: The Twentieth Century and the Birth of Audio Technology - Some

thoughts on where we've been, and where we might be going (continued)

An industry was being born, but nobody knew it! In 1946, we named it: High Fidelity! A tight little group of engineers, linked mainly by their desire for improved playback of their own music, emerged between 1935 and the outbreak of WWII. Their work slowly developed on both coasts, primarily in New England, New York and California. Several young engineers, asking educated questions about methods for creating clean, dynamic sound, set the stage for rapid audio progress after the war. From various engineering specialties, sound reinforcement, broadcasting, movies and university engineering departments, a far-reaching project was set in motion. Almost without realizing it, the founding members launched an industry whose only goal was to reproduce recorded sound with extraordinary quality. Meanwhile, on the theoretical front, new thinking began to change amplifier, loudspeaker and enclosure designs. New frontiers in basic acoustic science and advanced sound recording technology were proposed, discussed, tested and published. An industry based solely on high quality sound was emerging and expectations ran high. But, again with the Axis powers bent on conquest in the Far East and Europe, the projects had to wait until everybody got back from the war. Audiophilus Interruptus As you all know, World War II happened all over the place. Consumer audio, radio and television development came to a halt virtually overnight. It was turned into radar and radio research and manufacturing. Consumer product manufacturing was converted to wartime needs in just a few months. We made every kind of war related product you could imagine. Rationing became a way of life for everybody involved in WWII, here and abroad. In those crucial several years, America and its allies got busy and settled a few scores in Europe and the Pacific. There were grievous losses for everyone with millions dead and, except for the U.S. and Canada and most of the Western hemisphere, an almost totally destroyed manufacturing capability. However, the technical knowledge gained from six years of wartime laboratory research was enormous. Most of that research spilled over into consumer products eventually. It's a gruesome fact, but true, none the less, that the same science that makes possible the greatest efficiency in killing people often has consumer applications. Science is science! World War II gave us major advantages with welcome new materials: synthetic fibers, new molding resins, advanced alloys and metallurgy, great new plastics, super-efficient magnetic materials, stronger adhesives and synthetic rubber compounds. On the technology front we gained advanced radio and radar designs, new measuring circuitry, the first computers, magnetic tape recording, ultra-sensitive microphones, improved vacuum tubes, new transformer designs and new, efficient manufacturing methods. A vast increase in pure science and technical knowledge accrued to the allies, too. WWII's influence on the advancement of consumer audio and video was remarkable. As they say in the good old board room: "Today the defense department, tomorrow the world."

Due to the huge post-war need for accurate electrical measurements, Hewlett-Packard got their late '30s company re-started in 1946. They'd begun in a California garage in 1938 with a $5000 nest egg, and 1946 was their time to howl. Here in Portland, Oregon in 1946, Howard Vollum and Jack Murdock started Tektronix to build oscilloscopes, a relatively new device, and extremely vital to audio development and analysis. The G.I. Bill gave us freshly minted, high quality engineering grads who poured out of our universities and into our post-war production plants. Television began in many major cities in late 1946-1947. By 1950, the nation's retailers were selling 100,000 sets a month! Home audio resumed its pre-war mission of giving every music lover greater realism in his home listening room. Audio's Golden Age: Approximately 1950 to 1970 A disputed time period. Everyone agrees there was one, but the debate still goes on about when it occurred. I've chosen this 20 year window as being the two representative decades of major audio growth, innovation and change. It brackets most of the biggest technical milestones and later refinements right up to the advent of digital recording and playback. See if you agree. The First Epoch of the Rusty Ribbon: Iron Oxide builds a better mousetrap! A development of legendary status. From the enterprising electrical engineers of Hitler's Reich came magnetic tape recording. Not wire recording like we were still messing with in the U.S., but magnetic tape! The first tape was paper-based and truly a pain in the ass to use because of flaking and breakage. Replacing the original paper tape in 1939, German BASF first used cellulose acetate film, the best plastic film that was available. Better than paper, but still no cigar! A real sonic breakthrough came in 1939 when German radio network engineer, Walter Weber, injected ultra-sonic AC bias frequencies into the recording signal. The addition of high-frequency AC bias at the record head improved high frequency recording characteristics and reduced distortion.

As the improved tape recorder inched closer to real musical quality, America's 3M in Minnesota devised modified iron oxide formulas, developed safer oxide milling (iron oxide particles can burn or explode) and, finally, 3M scientists perfected the binders to hold the new metal oxides on acetate tape stock. In 1947, 3M's new binder and oxide formulations insured that many of audio tape's problems were well on their way to being solved. The output and distortion numbers improved with the new tape and the oxides didn't flake off on the heads as they had before. By the late 40's tape speeds were trending downward from 30 IPS (inches per second) to 15 IPS for most commercial purposes due to further improvements in record and playback EQ curves, aided by continued blank tape refinements. The first major artist to express interest in tape recording for broadcasting in the 40's was American entertainer Bing Crosby. Crosby became a major influence in the destiny of a new California company, the Ampex Corporation when he ordered the earliest Ampex recorders. Crosby had a logistical problem, and Ampex provided the solution with machines using 1/4" tape and operating at 30 IPS. His national live weekly radio show on the ABC Radio Network was popular nationwide. Covering all 5 time zones of the U.S. before tape recording, made it necessary to perform his live show twice. Crosby's show covered half the U.S. time zones with each performance, first the three eastern time zones and then 3 hrs. later, the western time zones. It was a tiring and frustrating weekly grind, so with audio tape, he could do the show once, have it edited and go home. The scheme worked very well and the rest, as they say, is history. Crosby became a major investor in Ampex, and soon all radio broadcasting depended on their tape machines. (As a further note, in the mid-'50s, Ampex also developed the first black and white video tape machines to replace the process called kinescope.) Magnetic tape became the best musical recording medium for producing records and, by 1950, became the method of choice. Replacing the hardships of direct to disc mastering with the more forgiving reality of magnetic tape, the big Ampex machines became a major economic and technical breakthrough for record producers. By 1952, tape was achieving decent dynamic range, noise figures, and a consistent 30 Hz to 15kHz frequency response. Improvements like this finally brought magnetic tape to the recording studio as the first adequate replacement for direct cutting of lacquer disc masters. Taped recording sessions offered a unique advantage over direct-to-disc cutting because taped masters allowed editing options not available before in any medium. And taping was far more portable, not requiring any permanent on-site equipment or a control room for the disc cutting lathes. Further, the maximum recording time with tape was many times the side length of a 78 lacquer and longer takes became possible. Retakes were greatly reduced with editing because you could remove a bad note with scissors. The Long-Playing Record: The invention that completely changed an industry Nothing in the history of recordings changed the character of the music business the way the LP did. When we got the ability to tape the recording sessions, edit them and, for the very first time, enjoy the LP side length of un-interrupted playing time, the record catalogs changed drastically. For long works, 3 LPs could take the place of a dozen or more 78's and 24+ side breaks. The lack of side-change interruption and the markedly lower surface noise available on vinyl pressings spoiled us for anything less. Works that had never been recorded before became almost commonplace. But, unfortunately, there were quickly two dozen Beethoven 5th Symphony recordings in the catalog. Immediately, un-needed duplications began began popping up like spring flowers in the catalog—a problem that is still with us in the CD era.

RCA's Classical Red Seal division finally adopted the LP for its extended playing times and quiet surfaces. (RCA, a pioneering company to whom we owe so much, is famous for several corporate decisions that left us totally puzzled, about which more later.) Early LP's and the turntables to play them, however, were not widely available before about '52/'53, and early LP frequency response and dynamic range was still limited. Worse, the equalization curves had not been standardized yet! There were several curves in 1953. Furthermore, many of the initial LP releases came from old 78 rpm lacquers and had the 78 masters' shortcomings and few of the strengths. (Frequent, hard to conceal side breaks while losing much of the original 78's vividness in the LP transfer.) Fortunately, LP cutting heads kept improving giving us ever-lower distortion, wider bandwidths and improved dynamics. As usual, phono cartridges and turntable systems had a rough time keeping up with advancements in the cutting process and fell behind. Phono cartridges of the '50s were as subtle as a 16 penny nail in a 2x4, requiring heavy tracing forces, still very high stylus and cantilever mass, and inefficient magnetic structures. Diamond stylii weren't even standard for micro-groove records until after the mid-50's. Synthetic Sapphire and a hard metal tip called Osmium were used in place of diamonds in cartridges such as the popular G.E. Variable Reluctance models. Another problem was the narrower groove at its slower tracing speed, especially near the inner diameter of the disc. The stylus was subject to serious inner-groove distortion problems, ironically right where the composer wants to place his bang-up finale in most classical pieces. Cutting levels were kept low for that reason, and with the low cutting levels, surface noise began to catch up with the inherently quiet vinyl compounds used for pressing the LPs. One factor was nullifying the other; not a good thing. LP playback equalization became standardized in the mid-fifties after several years of non-standard curves. Most pre-amps and integrated amps had multiple playback curves on a selector. The RIAA curve became a standard eventually, and none too soon. Gunfight at the O.K. Symphony Corral: Mercury Records called it "Living Presence" Ooh! Ooh! Quantum leap time! When Mercury Records of Chicago, under their resident recording genius, Bob Fine and his disc cutting whiz, George Piros, launched their "Living Presence" series of mono classical recordings, most audiophiles 'bout messed their drawers! It was 1953, a generally unpromising year and out of the blue, the Chicago Symphony under Raphael Kubelik jarred the industry clean out of its comfort zone with the justly famous Mussorgsky/Ravel Pictures at an Exhibition. It was big, it was bold, it was a visceral punch in the gut! On that first "Living Presence" mono LP release, the results were quite startling, and widely reported by record reviewers across the nation. In just one release, Mercury scooped everybody and achieved big sound, clarity, dynamics and a dramatic "you-are-there" quality. And the attention of all LP fans was upon them! "Living Presence" grabbed the audiophile community by its short and curlies and "Pictures" became an instant demonstration disc. What was so different about this release? First, its simplicity. Only one Telefunken U-47 condenser mike was placed in front of and above the orchestra, just forward of the podium. The mike pre-amp was fed into the in-house modified Ampex 30 IPS tape console and, after minimal editing, the session tape was mastered to disc by George Piros on his advanced cutting lathe at the highest levels he thought he could get by with. Piros was a genius. He found ways to get the cutting levels up and the distortion products down. Part of this was his use of something called "variable groove spacing", especially useful in the inner grooves. Mercury's "Living Presence" LPs rewrote recording history. In slack-jawed surprise, RCA and British Decca took this as a direct challenge. In 1953, everybody was determined to produce some of the greatest mono LPs in history. And they did. This "Golden Age" Thing Was Kickin' Into High Gear! On the studio side, microphones became very sophisticated. RCA produced many of their finest dynamic mikes in their own research labs, including a couple of superb ribbon designs. From war-ravaged Europe, Austrian AKG and German Telefunken re-emerged stronger than ever, recovering from the recent unpleasantness. In the late '40s, they prototyped and manufactured several advanced condenser microphones utilizing new diaphragms and good low noise tube preamplifiers. Some of our legendary recording engineers of the '50s used German and Austrian condenser mikes almost exclusively.

The Second Epoch of the "Rusty Ribbon": Left channel! Right channel! Fall in, troops! The other shoe dropped. Without any fanfare, stereophonic taping of most Mercury and RCA recording sessions began in '54. At first it was experimental, and then became standard procedure. These dates almost coincide with the re-introduction of stereophonic sound at the movies, and they're probably related. In 1953, multi-channel stereo, wide-screen spectaculars started pouring out of Hollywood studios and into our local theaters. By 1955, British and European record companies got the word, too. Stereo was coming and was ready to kick in the door! Several companies, large and small, began releasing stereo recordings on 7 1/2 IPS, half-track tape for the home listener in 1955 and 1956. Ampex produced the best 1/2" studio tape machines available, and quickly became the industry standard. Ampex also produced a series of smaller portable semi-pro 1/4" tape machines for home and audio visual markets and, though quite expensive, these were the best units for stereo playback in the home. RCA and Mercury open reel tapes were carefully produced and real time duplicated on good recording slave machines from an early generation edited duping master. The effort was worth it. They possessed good dynamics, no serious overload problems, clean, sweet detailing, and all the heady excitement my 16 year old ears could handle. Stereo tapes and the playback decks were too expensive in mid-'50s dollars for the average buyer, but RCA and Mercury produced them anyway as a calling card, a prestige product. I'd have mortgaged the farm to have a good stereo tape system, but I didn't own a farm, so I couldn't mortgage it, could I? Sigh! They were clearly anticipating the home market for stereo LPs when the technology became available. In the meantime, the tape would do very nicely. (For a cost reference, in BIG, uninflated 1956 dollars, the typical RCA Red Seal Mono LP was $3.98 and the RCA stereo tape issue of the same performance was $16.95, not pocket change back then.1 The Ampex 600 series deck to play them on was about $600. Ouch! $600 would buy a really good used car, and a stripped Plymouth coupe was $1400 new.) 1 Indeed not! And to think that audiophiles complain about SACDs at $19.95 - $24.95, or quality 180 gram LPs for $30.00… for shame! By 1956, stereo half-track tape was available from several other companies, too. One of the better late entries was pre-EMI Capitol Stereotapes. Their late '50s jazz, Sinatra, Peggy Lee, Hollywood Bowl and various other classical recordings, (now on EMI re-issue CDs) were excellent, and their half-track tapes sounded almost as good as RCA and Mercury. Before 1958 and the stereo LP, tape was the only multi-channel sound source available to the consumer except for a few odd dual-band LPs produced by Emory Cook for the rare two-headed Livingston tonearm. The single-groove stereo LP was still a couple of years in the future. A whole lot of frantic R&D was going on in the labs at Western Electric, RCA, Fairchild Instruments and others to develop a single-groove stereo cutting system. Several stereo disc cutting techniques were considered here and in Europe, but when the choice was finally made, the Westrex 45/45 cutter won the contest. Like any far reaching standard that gets adopted, Westrex' cutter was a mixture of technical strengths and political realities. As it has turned out, it's served us rather well, don't you think? Dedication I would like to dedicate this article on the "Audio Century" to my friend and long time colleague, David G. Morris. Last March 23rd, 1999, David had a fatal coronary and left behind his many friends in the audio and train club communities. David was my friend for over 31 years, and his early death at age 54 has left a large void in my life. A dedicated audio enthusiast, David's 2000 sq. ft. house featured three audio systems plus a video surround system. Having logged three decades in his audio hobby, he was also a regular at the Oregon Triode Society meetings in the early 90's. His insightful observations and the discussions we had through the years have influenced this pair of articles in very positive ways. I still reach for the phone to tell him the latest news because he was there for so many years. Now he isn't… To be continued in Issue 15.

|

Let's

return to the guys who launched serious audio in the late thirties: Avery

Fisher, Herman H. Scott, Rudy Bozak, Frank McIntosh, James Lansing, Jim

Stephens, Paul Klipsch (pictured, left), Saul Marantz, David Hafler and several others. Their

counterparts across the Atlantic, Briggs, Williamson,

Walker, and Leak, to name a few, were in the U.K. These were the High-Fidelity

industry pioneers, still in their twenties and thirties. They returned from the

war anxious to set up shop and get back to business, utilizing the new

technologies as a peacetime bonus.

Let's

return to the guys who launched serious audio in the late thirties: Avery

Fisher, Herman H. Scott, Rudy Bozak, Frank McIntosh, James Lansing, Jim

Stephens, Paul Klipsch (pictured, left), Saul Marantz, David Hafler and several others. Their

counterparts across the Atlantic, Briggs, Williamson,

Walker, and Leak, to name a few, were in the U.K. These were the High-Fidelity

industry pioneers, still in their twenties and thirties. They returned from the

war anxious to set up shop and get back to business, utilizing the new

technologies as a peacetime bonus.

Late production "Magnetophon" tape machines were

brought back from Europe by U.S. Army Signal Corps personnel at war's end.

American and British audio engineers set about refining the German machines.

Advances came rapidly. After standardizing tape speeds, tape dimensions and

solving a few lingering mechanical questions, they began improving record and

playback heads and record electronics.

Late production "Magnetophon" tape machines were

brought back from Europe by U.S. Army Signal Corps personnel at war's end.

American and British audio engineers set about refining the German machines.

Advances came rapidly. After standardizing tape speeds, tape dimensions and

solving a few lingering mechanical questions, they began improving record and

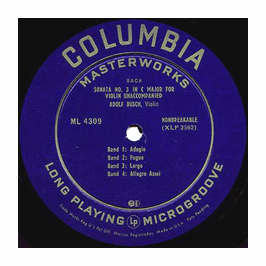

playback heads and record electronics.  Fifty two years

ago in October, Peter Goldmark and William Bachman of CBS Labs

publicly demonstrated the first LP record. It was the Fall of 1948.

Microgroove 33 1/3 RPM, 12 inch records achieving over 20 minutes side

length created quite a stir. Poor, stubborn RCA, in the first of four really

dumb marketing decisions of the past five decades, publicly announced in 1949

that what the public really wanted was the small 45 RPM 7" discs and a rapid

changer mechanism to play them. RCA threw their corporate might behind the 45s

for a couple of years. When it failed miserably for classical and other extended

programming, they capitulated. With abysmal sales figures virtually tattooed on

their foreheads, the embarrassed board members decided the 45 RPM record would

serve the singles market for the teeny-boppers. (Got any original Elvis?)

Fifty two years

ago in October, Peter Goldmark and William Bachman of CBS Labs

publicly demonstrated the first LP record. It was the Fall of 1948.

Microgroove 33 1/3 RPM, 12 inch records achieving over 20 minutes side

length created quite a stir. Poor, stubborn RCA, in the first of four really

dumb marketing decisions of the past five decades, publicly announced in 1949

that what the public really wanted was the small 45 RPM 7" discs and a rapid

changer mechanism to play them. RCA threw their corporate might behind the 45s

for a couple of years. When it failed miserably for classical and other extended

programming, they capitulated. With abysmal sales figures virtually tattooed on

their foreheads, the embarrassed board members decided the 45 RPM record would

serve the singles market for the teeny-boppers. (Got any original Elvis?)

LP cutting heads

kept getting better, too. With clever innovations like heated cutting stylii and

variable pitch cutter drive systems, many of our inner-groove distortion

problems diminished. With heated cutter stylii, groove formation on the lacquer

masters was smoother and quieter, yielding better plated mothers and stampers.

As the cutting lathes underwent mechanical improvements, cutting

amplifiers got special attention. For the first time, high-powered,

low-distortion amplifiers were specifically matched to the special needs of

cutting heads. In the '50s, Mercury commissioned McIntosh Labs to develop a

custom 200 watt tube amplifier for their hot-rod Westrex cutting heads. Alas,

the phono cartridge, arm and turntable systems still lagged far behind. I found

out the hard way that in '54 and '55, you could still buy a Mercury LP and take

it home only to discover that your turntable wouldn't play it without serious

mis-tracking. Early arm and cartridge combinations would either jump right out

of the groove or, worse yet, plow right through it leaving vinyl shavings in

their wake. The nagging question of Turntables vs. the LPs was touch and

go for most of the LP's history. LP's were usually ahead of the playback unit's

ability to play them optimally. Chicken or the egg? Egg or the Chicken?

Omelet?

LP cutting heads

kept getting better, too. With clever innovations like heated cutting stylii and

variable pitch cutter drive systems, many of our inner-groove distortion

problems diminished. With heated cutter stylii, groove formation on the lacquer

masters was smoother and quieter, yielding better plated mothers and stampers.

As the cutting lathes underwent mechanical improvements, cutting

amplifiers got special attention. For the first time, high-powered,

low-distortion amplifiers were specifically matched to the special needs of

cutting heads. In the '50s, Mercury commissioned McIntosh Labs to develop a

custom 200 watt tube amplifier for their hot-rod Westrex cutting heads. Alas,

the phono cartridge, arm and turntable systems still lagged far behind. I found

out the hard way that in '54 and '55, you could still buy a Mercury LP and take

it home only to discover that your turntable wouldn't play it without serious

mis-tracking. Early arm and cartridge combinations would either jump right out

of the groove or, worse yet, plow right through it leaving vinyl shavings in

their wake. The nagging question of Turntables vs. the LPs was touch and

go for most of the LP's history. LP's were usually ahead of the playback unit's

ability to play them optimally. Chicken or the egg? Egg or the Chicken?

Omelet?