Those who've read past articles know my admiration for the recordings of independent Dutch recording and mastering engineer Bert van der Wolf (now and hereafter, in honor of his recent marriage, Bert van der Wolf-Oude Avenhuis), Northstar Recording Services. Bert's recordings are a touchstone of excellence. He captures acoustic music in a most engagingly natural manner, with the full ambiance of the acoustic setting of the performance, the natural timbre of the instruments, the extended range and harmonic overtones that make music come alive, and the subtle detail and micro-dynamics that make the recording sound as close to "real" as it gets. So, I watch for his recordings, on whatever label they may appear. Any day I spend with music recorded by Bert is a fortunate day, a day well spent. So, here are some recent recordings that are close to magical. Thank you, Bert.

Korngold & Fauré 1921, Chianti Ensemble. Oak | Northstar 2025 (DXD, DSD256) HERE

With this album we hear two masterworks, both composed in 1921 but one evidencing the emergence of the new modern era in the Piano Quintet, Op. 15 by a young Erich Wolfgang Korngold, and the other memorializing the closing of Romanticism with the Piano Quintet, Op. 115 of Gabriel Fauré.

Beautifully performed by the Chianti Ensemble, these two piano quintets are a study in contrast. The Korngold with lush, expansive, bold statements. The Fauré with a refined beauty of tone, long line, and subtle interweaving melodies. So, Ann asks, "Do you have a favorite?" Oh my goodness—what a painful question to ask of me! It depends on my mood, it depends on the position of the stars. But, if forced to choose, then admittedly it will be the refined and graceful Fauré. The master's skill wins out for me. But why choose? Enjoy both. Both are worthy.

And both are enchantingly, immaculately, played by the youthful Chianti Ensemble.

Formed after a series of chamber music concerts in Tuscany, the Chianti Ensemble, comprised of Shin Sihan, Yamen Saadi (violins), Takehiro Konoe (viola), Alexander Warenberg (cello), and Nathalia Milstein (piano), received the prestigious Kersjes Prize in 2022 for their artistic excellence. They are exciting young musicians on the European classical scene from whom I hope to hear much more.

Chianti Ensemble in recording session (above), and with Bert van der Wolf below.

Beethoven Late String Quartets, Narratio Quartet. Challenge Classics | Northstar 2025 (DXD, DSD256) HERE

With this release, the Narratio Quartet brings its monumental cycle of the complete Beethoven string quartets on period instruments to a resounding, sumptuous close. What a great cycle this is—and what a marvelously rewarding conclusion is this final volume. This is a cycle every lover of great chamber music must include an any music library. It is stunning. It is superb.

Johannes Leertouwer - violin

Franc Polman - violin

Dorothea Vogel - viola

Viola de Hoog - cello

About the cycle, Narratio Quartet cellist Viola de Hoog writes:

I have often wondered which of the "great spirits" might provide a new impulse and a different direction for what we call classical music in this early part of the twenty-first century. Narratio Quartet have been immersed in all of Beethoven’s string quartets for over fifteen years now. We experience time and again how Beethoven explored and then overcame the limits of the Classical style and the instrumental difficulties that were prevalent at the start of the nineteenth century. What we hear has been enriched by the passing of two centuries and the gaining of wider experience. Progress indeed, might be your first thought, but perhaps we have also lost something along the way? The ability to feel how groundbreaking and visionary this music was in those days. My colleagues and I feel that using instruments that are comparable to those of the time has helped us enormously in getting somewhat closer to the surprise, the bewilderment and the rapture that the musicians in Schuppanzigh’s quartet must have felt when they first came face to face with the newest and most innovative chamber music of the day.

Containing some of the greatest music Beethoven ever set down, this album took quite a while to listen through, and then listen through again. It is a massive collection of music, music of profound complexity and intelligence, and of sublime beauty. It will also challenge the socks right off you. So, take it in bites, not all at one go, is my recommendation.

As I listen to these performances, the thought that keeps coming to my mind is that these musicians are welcoming old friends. This is music they appear to know deeply in their bones. There is a level of comfort to their playing reassuring that these players are on familiar ground, and a familiar ground that they love deeply. Yet nothing sounds taken for granted, so please do not misinterpret this observation. It is simply that the music flows so effortlessly from the four that one feels in the hands of a trusted guide, knowing that the music will unfold with all of its complexity and nuance.

And I will not, not I absolutely will not, attempt to parse this out in music reviewer-ese. You simply have to listen and experience these performances for yourself. I highly recommend that you invest your time and energy to do so. I am convinced you will be rewarded in your efforts as you hear some of the most excellent performances of these works in the catalog. Are there other or better performances? Oh, don't be silly. These compositions demand alternative interpretations, alternative visions of how this music can be played. There is no one "best"—there are simply choices and alternatives.

For me, the Narratio Quartet make some outstandingly good choices.

Starting with their decision to use period instruments—they open up an entirely new view of this music as compared to modern instrument performances. Again, is this better than using modern instruments? And again, come on! These are musical explorations and experiences. For me, to hear these works performed on period instruments is a superb experience that just doesn't get much better—the texture, the nuance, the complexity of overtones... It is all simply grand.

I have appended to this article a repost of violinist Johannes Leertouwer's discussion of performance practice considerations from the enclosed booklet, with permission. It is an excellent explanation of vibrato, tempo and portamento that I encourage you to read to better understand the choices made by the quartet in performing these works. See "Working with 19th-century expressive tools in Beethoven’s string quartets" below.

Narratio Quartet recording session in Evangelisch Lutherse kerk, Haarlem, The Netherlands, 2024

The narrative of the Amsterdam based Narratio Quartet began in 2009 when it was invited to perform Beethoven’s last five string quartets on five consecutive nights at the Early Music Festival Utrecht. It is precisely these late Beethoven quartets which are rarely played on period instruments, using gut strings and 19th-century bows. Since then the quartet has worked backwards and here presents the complete cycle of Beethoven quartets. Their repertoire has expanded to the later 19th century with Brahms, Schubert, Schumann and Mendelssohn.

My earlier review of Narratio Quartet's release of Beethoven Early String Quartets can be found HERE should you like to read it.

The Beethoven Early String Quartets and the Middle String Quartets HERE

L'entropia, Lina Tur Bonet & Jadran Duncomb. Glossa | Northstar 2025 (DXD, DSD256) HERE

Ah, just an utter delight. The ever engaging Lina Tur Bonet partners with theorbo player Kadran Duncomb to create an album that is both unusual and distinctive.

Bonet writes, "Entropy symbolises the change of directions through unexpected twists and turns when two musicians make music from the moment, for the unpredictable, for the infinite possibilities that a piece carries within itself. The spontaneity of the two players' reactions allows the freedom and creativity of the stylus fantasticus in 17th century violin music to blossom in a completely new way."

With a feeling of improvisation, and sometimes of abandon, Bonet and Duncomb dance their way through a string of 17th century gems. The violin contrasts nicely with the plucked notes of the theorbo to create a soundscape that is both different to one's ears, yet still comfortably familiar. Duncomb's substitution of baroque guitar on some cuts makes for a nice variation in texture and sound.

Why theorbo? Oh, it is an excellent accompanist instrument. It has a wide variety of color and range of sound. Duncomb writes, "Somehow, its clunkiness and absurd tuning (the result of making an instrument so big that the top two strings would snap at the right octave) create an instrument more complete than any other lute, less intrusive than a harpsichord, and more versatile and colorful than an organ or harp when realizing the continuo of chamber music from this era. Its long string length allows the bass to resonate and sing while its tuning allows the theorbo player to roll the long chords where the individual notes are indistinguishable, creating the illusion of a long sustained, or even growing note. The latter is particularly useful in music where the bass has a lot of very long notes."

Virtually all of the music on this album was unknown to me, which was a great delight! So often we hear well-trod repeats of music heard time and time again. Not here! Our artists demonstrate that there is so much excellent music of the 17th century still to explore. While quite a few pieces were from composers with whom I was familiar (e.g., Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger, Giovanni Battista Fontana), the music was almost completely new to me. And I listen to a lot of baroque music. So, happy times prevailed as I listened the first time through this album.

I recommend this album to you most highly. Bonet and Duncomb will delight you. The variety of music will likely be fresh to you. It certainly was for me.

And the recording quality, oh my... The recording quality is that for which I look forward to with each new recording from Bert van der Wolf-Oude Avenhuis. Recorded at MuziekHaven Zaandam, Amsterdam (The Netherlands), 17-19 July 2024, the sound captured is as delicately, delightfully, detailed, open, and transparent as any recording in my music library. Listening to the DXD stereo release, I close my eyes and feel transported. And I admit I would love to have a full surround sound audio system because I fully believe that Bert's full 5.1+4 Discrete Immersive recording would be yet a further world of audio reproduction excellence.

Lina Tur Bonet and Jadran Duncomb at recording session in MuziekHaven Zaandam.

And here are some other albums from Lina Tur Bonet, also recorded by Bert van der Wolf-Oude Avenhuis, that I highly recommend to you. You can read my earlier reviews HERE and HERE.

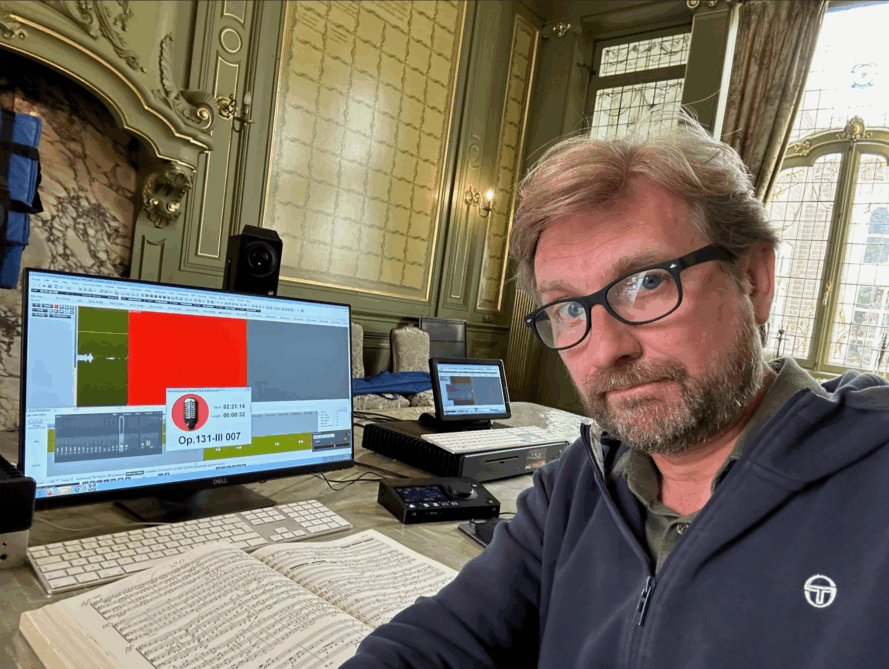

Bert van der Wolf-Oude Avenhuis, the consummate master of acoustic recording

To explore further the recordings of Bert van der Wolf-Oude Avenhuis from my perspective as a listener who appreciates the work he accomplishes, you might visit this search link to other articles, and an interview, previously published on Positive Feedback HERE.

Working with 19th-century expressive tools in Beethoven’s string quartets

By Johannes Leertouwer, reposted with permission from the enclosed booklet contained in Narratio Quartet's album Beethoven Late String Quartets reviewed above. I've reposted this because it is an excellent discussion of performance practice to help listeners better understand the choices being made in the performance of any music from this period.

Tempo

Research has demonstrated that the 19th century concept of tempo was much more flexible than the stricter adherence to metronome markings that became common in the 20th century would suggest. Composers such as Beethoven would have expected un-prescribed modifications of tempo and certainly also of rhythm, from performers playing their music.

In fact, there is much evidence to suggest that such modifications were an important and integral part of the revered ‘German style’, which was championed by Louis Spohr and Joseph Joachim. With the Narratio Quartet, we have experimented extensively with flexible tempo and rhythm. Once we had abandoned the rule of keeping a steady tempo throughout, we shaped our idea of what 19th-century flexibility might have sounded like in performance, largely based on our intuition. After all, we are not trying to recreate a historical truth, but we are trying to use 19th century expressive tools to perform as 21st century musicians for a 21st century audience. It has been striking for us to experience that ideas of flexibility of tempo and rhythm can be applied, not only in the revolutionary later quartets, but also in Beethoven’s Opus 18, generally considered to be more classical or Haydnesque

Vibrato

In the violin methods by Spohr (1833) and Joachim/Moser (1905), vibrato is described as an ornament, to be applied only in special circumstances, not—as is common today—as an omni present element in sound production on stringed instruments.

There is much evidence to suggest that vibrato was used as an expressive tool to embellish individual notes in melody lines or to colour specific passages or themes. Furthermore, the use of vibrato was often connected to sforzati, accents or expressive signs, such as hairpins ( <> ) or the term ‘dolce’ in the score. Although it is clear (if only from the many warnings against it) that over the course of the 19th century, vibrato became more and more prominent, we feel as a quartet that much can be gained from using it sparsely. Not only does this create possibilities to highlight certain passages or notes, contrasting them to the ones without vibrato, but it also creates a transparent sound in which the harmonic tensions and resolutions can be felt very clearly. Finally, we think that the harnessed powerful intense vibrato sound, is not always helpful in portraying more delicate and fragile ideas, which seem to constitute such an important and beautiful part of Beethoven’s quartets, the early ones as much as the later ones.

Portamento

Portamento is described in the violin methods of the 19th century as the most important expressive tool for string players, enabling them to imitate the human voice. Indeed, portamento is mentioned by Spohr and Joachim, before they discuss vibrato.

Over the course of the 20th century, as musicians began more and more to strive for a literal and precise representation of the printed score, portamento became less and less prominent. After all, it is very rarely marked in the score by composers and it takes place ‘in between the printed notes.’ The use of portamento can soften the rhythmic and melodic contours of the music. Just like vibrato, portamento was a hotly discussed topic in the 19th century. Some were accused of applying it too often others of not using it sufficiently.

We will never know how exactly it was applied in the German tradition of the era before truthful audio recording. For us in the Narratio quartet, experimenting with portamento has opened our ears to different ways of emphasising tension and relaxation in intervals, as well as the harmonic ebb and flow. We realise that it is an acquired taste, but we are strengthened by Beethoven’s enthusiasm for Domenico Dragonetti’s (1763-1830) portamento playing. Cipriani Potter, who was on friendly terms with Beethoven, writes that Dragonetti’s bass playing ‘led him (Beethoven) to imagine […] those slidings upon one string, which import so beautiful and spiritual a character to his chamber music’. Furthermore the violinist Ignace Schuppanzigh, who was such an important partner of Beethoven in premiering and (even in composing) the quartets is reported to have used slides (portamenti) extensively.