When I first encountered the vertical walls of houses and the hard, straight lines of streets I was still suffused with a memory of something altogether different. It's no easy task to describe this memory. I guess I knew it mostly by contrast to the new world into which I was suddenly dropped.

After all, how does one describe invisible physicality? As soon as I use a word like spiritual I know I'm going to lose somebody. Bright or ghostly maybe? But ghostly still has a creepy connotation and this was anything but creepy. But it was of another realm, and—I cannot find a more accurate description—it most assuredly was of the spirit.

It was a memory of warmth and comfort, but certainly not cozy. There was a vast majesty to this embracing environment. But it knew me. Better than I've ever been able to know myself. Besides this, somehow I knew the one who knew me was kind.

It would be too easy to say this recollection was only of the womb. No, there was a much deeper origin. The memory has never left nor have I been able to shake it. But the harsh delineations of the world into which I had been placed were distinctly different, and anything but kind.

To be fair, not everything I came up against was unyielding. There were bushes and trees in our backyard, and weeds in the cracks. Grass yielded to the touch, but even grass was managed, cut back to match the lines of poured cement. Of course, weeds were plucked.

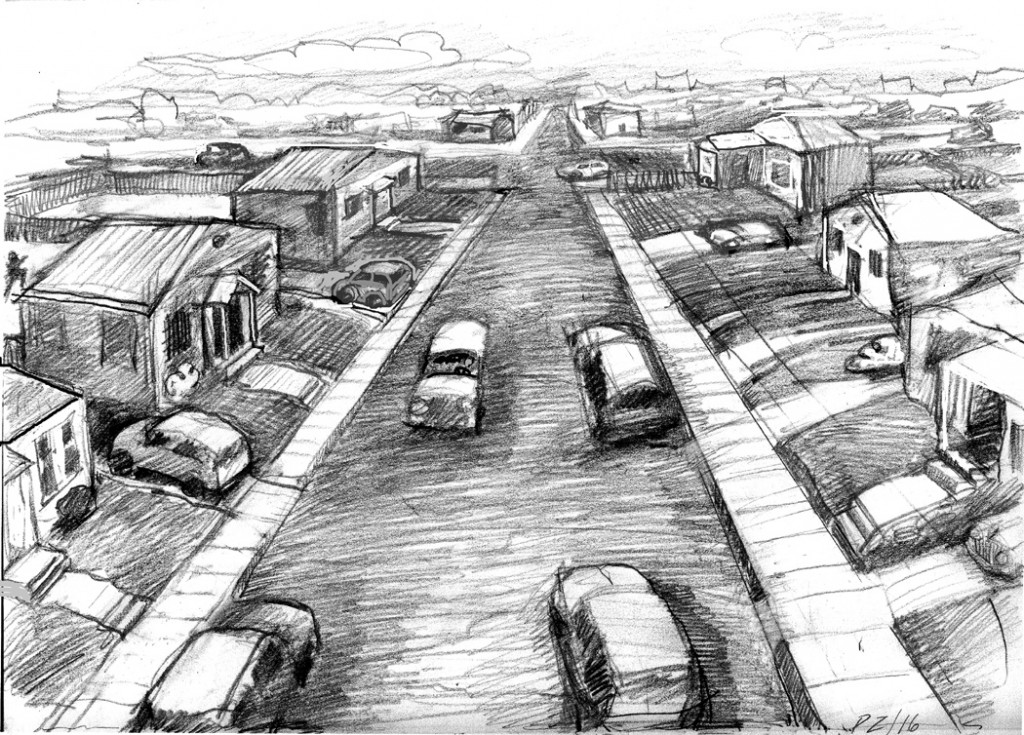

The general theme here is that it all felt so alien to me. I was still used to something much more giving. It was the fifties and my family lived in South Central Los Angeles, a terrain dominated by the hard and the straight.

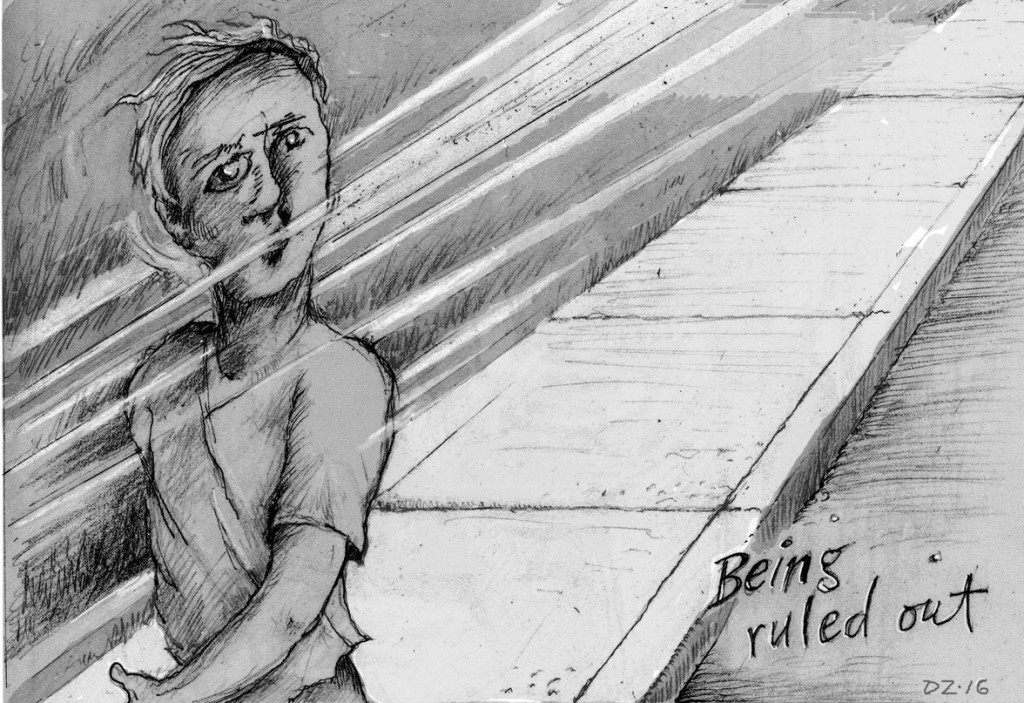

It seemed unavoidable. The world's demands were insistent. “Wake up. It's time for you to get in line, young man!"

So gradually I familiarized myself with these commanding characteristics. There was the severity of concrete, the unyielding resistance of metal. I fell onto a steel grate once as a child, and still have a scar where it split my nose. There were hard, awkward boxes called cars and confrontational abutments known as houses. Architecture in general. These were things that did not yield or give to the touch, things that caused pain when you collided with them.

As is characteristic of suburban neighborhoods, the houses were on rectangular plots of land surrounded by fences. My question was and still is - what are fences, anyway? The obvious implication here was that you couldn't go over there. Either that, or you needed to be protected from what was over there. And again there were driveways, sidewalks and streets stretching out in all directions, composed of asphalt, cement or other equally inhospitable materials.

When we traveled we crawled into automobiles, those strange, hard, albeit sleek capsules. And we passed people who were in their own respective encasing capsules.

So much was happening in my brain. Like, why does it have to be like this? Why all these separating lines and protective surfaces. Why the need for such severities?

Speaking of cars, I recall the time I performed a very personal experiment as a 5 year old. What if I just open the back door while our family's station wagon was rolling down the street? What if I just...step outside? What if I just refuse to let this metal box hurtle me along?

Of course I survived, but it certainly hurt when I hit the asphalt, and freaked my parents out. I think my brothers might have thought it was interesting.

Eventually the restrictive demands of the hard and the straight began to invade the inner sanctum; my family was violated by its unfeeling dictates. It was very hard. I'd assumed for a long time that my family was impregnable. The majority of this came later though and it deserves separate coverage.

In those early days of the fifties and sixties, however, my parents taught me something key, that it was possible to escape, albeit temporarily, from the world's unflinching dictates. I learned there was such a thing as legitimate rebellion.

Jumping out of our car's back door while we were driving was not a healthy form of rebellion, but fleeing to the mountains or the beach was.

My folks whisked us away on what we called "family days," usually to either the beach or the rambling hills of Simi Valley—where the Western movies were made which my father liked to watched on Sunday afternoons to unwind. We rolled, ran, climbed and tumbled, up and down the oaks and the piles of rocks and boulder. Like I said, it was either that or the warm sand and soft roar of the ocean. These places were all so much more familial than what we'd escaped from. They were like the cosmic home I recalled in the recesses of my consciousness, an environment I could interact with. You can't interact with cement, or rules.

The older I grew the more relentless the demands. I became all too familiar with the idea of necessity, stuff you just had to do. Obligation seemed to be inherent in very fabric of things. I really wanted something different, but it was like I had very little choice in the matter.

To expand on this, let me say that besides teaching me it was possible to escape for brief periods, both my parents, but especially my father, taught me the value of principled resistance. More on this later.

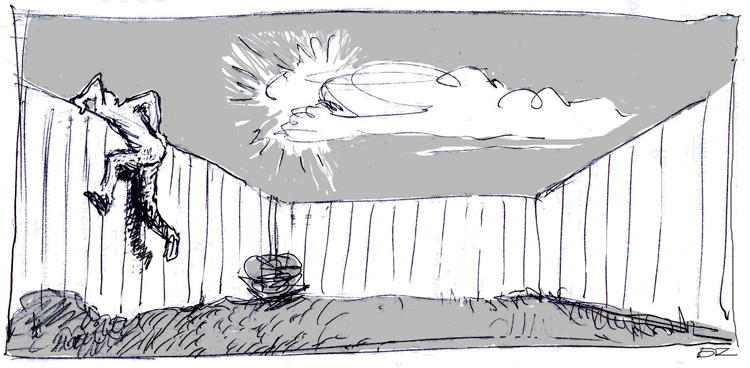

I was learning to fight back, to kick against the pricks. This is where the creative life began for me, when I refused to cave. It was only the beginning. My destiny beckoned, and my young soul did its best to respond. I was discovering that there was another way.

I could become a maker.

Of course, the tale of this discovery stretches through my entire life.

At first, however, I was mostly learning that sometimes I could say no.

In a respectful way of course. I still contend it was a holy revolt, because I contended with the things I was made to contend with.

Let me relate one of my earliest rebel acts. I was gazing out at the straight street I lived on, down the long line of houses on each side. I knew each house was supposed to be a separate unit, defined by property line and fence. I knew each address was a private residence. But these separations were what my little soul was chafing at.

I walked across the street and around the side of the house at the end of the block. As I gazed up at the backyard fence of the house on the northwest corner of 78th and Van Ness, a plan hatched. It wasn't a destructive idea, just contrary. I set about climbing over and into that backyard; then I scurried quickly and circumspectly across to scale the next backyard fence, scooting across the next yard and on and on down the entire block, finally emerging at the far end, at Cimarron and 78th. I'm looking at the map on Google now. That's 12 houses!

Before I wind this up I'd like to mention a couple more examples of how the hard-and-the-straight is enforced. Consider the lawn trimmer and the paradigm of the trimmed edge. The sharper the better. The dominating idea here is to keep the inherently wild nature of grass in check. To do so you must cut it. Sure, go ahead and celebrate your lawn, but keep it under control.

And lastly, we all know that we're expected to shovel the snow off our sidewalk, and that when we do so to shovel it all off, so that the lines match.

In both situations I have stopped trying to maintain a sliced edge. The lawn trimmer broke and I'm glad. As for shoveling my walk I've taken to doing it in an irregular fashion, creating a fanciful serpentine path.

Why am I making such a fuss about this? I've repeatedly mentioned how shocked I was by the strict dimensions I was being introduced to—after what I had known, after being known, in the infinite heart of the maker before I was born—after the rich, brief feast of love which was the family I grew up in.

Previously I have tried to paint a picture of how the loving continuum of the universe continued to echo in my heart. I heard it in the soft roar of the ocean, and in the contrapuntal harmonies of sublime music that washed over me in church.

But now I heard marching orders. It was like suddenly having my face shoved into a concrete wall after I'd been rolling in the warm surf.

Even though I was taught I could flee the city, I knew I had to find a better way to break free, something more effective than avoidance tactics.

If I could somehow mould matter rather than be moulded myself. If could shape life into something personal and new. I knew there was a greater reality but I needed to discover a way to tap into it.

How I found, and re-found this creative way, is why I'm writing and what I will be writing about from now on.