Everything you want to know about behind-the-scenes of the recording process of Blue Train album and which of the digital reissues of this jazz masterpiece are the best.

On September 15th 1957, John Coltrane walked into Rudy Van Gelder's studio in Hackensack and recorded a masterpiece album: Blue Train. It was the only album by a saxophone leader recorded for Blue Note Records.

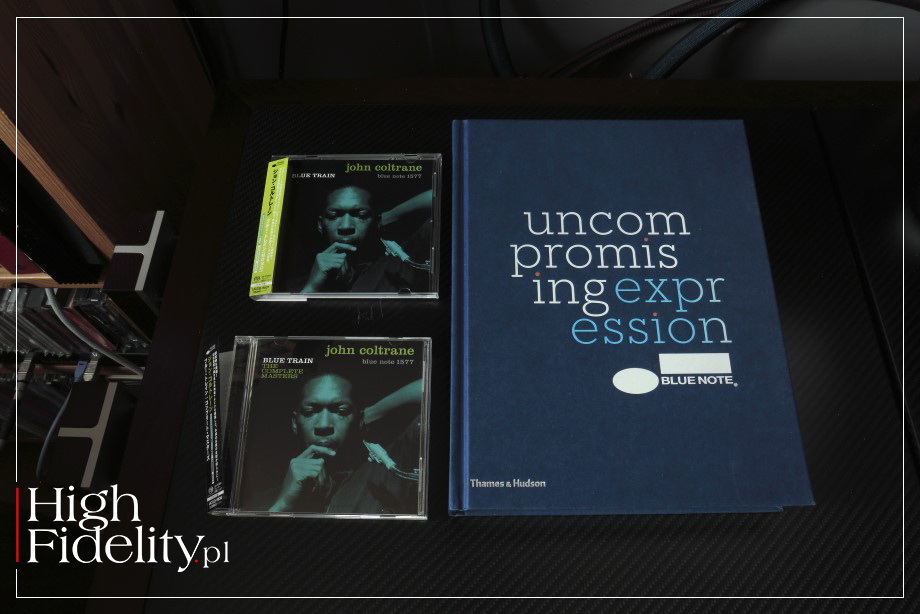

To celebrate the 65th anniversary of Blue Train, Blue Note presents it in the latest Kevin Gray's remaster and Joe Harley's production, both in mono and stereo versions. For the first time ever, we got a version with seven bonus tracks, none of which had previously been released on vinyl, and four of them not at all, in any format. This version is officially titled Blue Train: The Complete Masters. LP and CD versions hit the stores—the former single and double disc. Also part of this edition are previously unpublished photos by Francis Wolff and an essay by Ashley Kahn, an expert on Coltrane lore.

The number of Blue Train reissues is dizzying. The Discogs portal mentions as many as 285 versions. However, when we read the information revealed on the covers and in the booklets, when we look for information about them, it turns out that we are dealing with probably only nine remasters and thirteen most important CD and SACD releases. All others are based on the following ones:

- 1984 digital, Japan stereo

- 1985 analogue stereo

- 1991 analogue, Mobile Fidelity, Gold-CD stereo

- 1996 digital, Japan, PCM 20/88,2 stereo

- 1997 digital, Ron McMaster, PCM 20/88,2 | SBM stereo

- 1999 digital, Rudy Van Gelder, PCM 24/96MONO

- 2003 digital Rudy Van Gelder: Copy controlled DISC + SACD mono

- 2008 analogue, Analogue Productions, Kevin Gray & Steve Hoffman, DSD: SACD stereo

- 2015 digital, Esoteric, PCM 24/192 DSD: SACD stereo

- 2016 digital PCM 24/192, Platinum SHM-CD, SHM-CD, UHQCD (2017) mono

- 2017 digital, DSD, SHM-SACD stereo

- 2018 digital, DSD PCM 24/176,4: UHQCD

- 2022 analogue, DSD: SHM-SACD, UHQCD, CDMONO + stereo

Mono vs stereo

one of he most commonly discussed differences between Blue Note releases in the 1950s and much of the 1960s concerns their mono and stereo versions. In the list above, I deliberately marked which version I meant, because even the publisher could not always decide which "master" tape to use. Generally, it can be assumed that the Japanese most often chose the MONO edition, and the Europeans and the Americans the stereo edition. However, this is not an ironclad rule.

Most collectors believe that the former sound better, and therefore they fetch much higher prices at auctions. This is a technically based opinion. You see, when the first Ampex 200A tape recorder, and thus the first high-end reel-to-reel tape recorder, hit the market in April 1948, it used a ¼" tape, which set the standard for the entire industry. In Van Gelder's studio they used its successors, Ampex 300 monophonic tape recorders. A single mono signal was recorded over the entire width of the tape. So it was resistant to noise, distortion and the so-called "drop-outs," i.e. unevenness in the coating of the tape with ferromagnetic material.

When, in the early 1950s, Ampex engineers combined two heads placed one above the other, a stereo tape recorder was created, a variation of the 300 version. This tape recorder still used the same ¼" tape. This meant that each channel had only half its width at its disposal. So the signal had a lower level, higher noise and distortion.

This budding by dividing will repeat itself, starting with 3 tracks, then 4, 8, 16, and finally 24. Each step up involved dividing the available tape width - from ¼, through ½ and 1 all the way to 2 inches. Therefore, older devices using the same tape, but with fewer tracks, offered a technically better signal

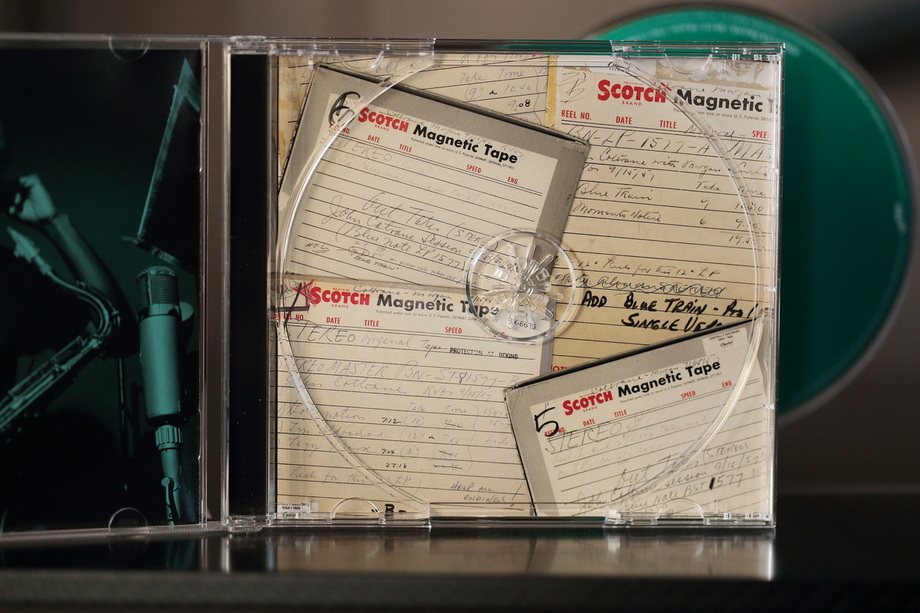

Stereo "master" tapes’ photos in one of the Blue Train releases

Van Gelder developed his technique with monophonic recordings in mind. He made his first stereo recording in 1956, experimenting with Atlantic Records engineer Tom Dowd. As Ashley Kahn writes in her monograph A Love Supreme: The Story of John Coltrane's Signature Album, followed by the RVGLEGACY.org website, Dowd brought his stereo tape recorder to the session, and Van Gelder a mono one.

The result of the comparison must have been promising, because a year later, on March 7th. 1957, Van Gelder's first professional stereophonic recording was made: Art Blakey's Orgy In Rhythm. Interestingly, it wasn't made in his studio, but in the Manhattan Towers Ballroom; the author of the recording used an Ampex 350-2P portable stereo tape recorder. Soon after, Blue Note began recording their artists in mono and stereo in parallel. Other labels, such as Savoy, Van Gelder worked for followed suit.

Ozzie Cadena, the producer of this label, recalls the sessions in Hackensack as following:

(…) We ran our monitoring in mono, whether we were recording in stereo or not. We recorded in stereo, but we listened to the sound in mono. And that's how we set the balance. Then we decided what would go left and what would go right. But, as I say, to some extent everything was audible in both channels. And that's how Rudy recorded the material. He recorded in a very "tight" way, thus capturing a kind of close stage. And thanks to this, he received a high separation of sounds without exaggerated separation of the instruments from each other. (Skea, p. 14)

Using the 'stereo' term in this context is an exaggeration. They recorded mono sources, and reverb. The mixing consoles of the time allowed the source to be placed only straight ahead, to the left and to the right, with no intermediate points. And so are placed the instruments on Blue Train. However, there is something else that makes us believe that they play in real space - the so-called. leakage, bleed or spill. Van Gelder recorded without screens dividing the musicians, because he had no space for them and this technique was rarely used at the time. The microphones "heard" not only the instrument they were standing next to, but also the neighboring ones. These were small signals, but they are what determine the credibility of the presentation.

Although the Blue Note label had both versions of the recordings, mono and stereo, they did not decide to release the latter right away. It took two years from the first stereo session before first titles with two channels were released on the market. These were Cannonball Adderley's Somethin' Else, Moanin' by Art Blakey and Finger Poppin' with the Horace Silver Quintet. First, they were released in a mono version, and after a few months they were joined by two-channel versions. The first title released by Blue Note simultaneously in both formats was Art Blakey's album Mosaic from December 1961.

The covers were initially printed in one form, and to distinguish the stereo version, a special gold sticker was glued to them. For comparison, Deutsche Gramophone used a different solution for their records - this label immediately began to mark such releases with a red entry inside the yellow label, characteristic for this label (1958, series 136 000). Decca, on the other hand, started flirting with stereo as early as 1956. However, it wasn't until the early 1960s and Kenneth Wilkinson of Decca Tree that a realistic stereo effect was achieved.

As we mentioned, one of the major differences between mono and stereo at the time was the width of the tracks. Equally important, however, was the difference in artistic expression between them. The recording engineer in each version had to pay attention to other aspects of the sound, mainly tonality and reverberations. So it is so that mono and stereo are two different musical events. And usually mono was what the sound engineers listened to during the recordings.

Releases

1984

The first digital version of John Coltrane's album appeared in Japan in 1984. A year later, this title was released in other countries. The lack earlier reissues was due to the fact that this recording label was inactive. In 1979, EMI acquired the United Artists Records, and moved the Blue Note to the "freezer." It wasn't until June 1984 that Bruce Lundvall was hired to resurrect it, mainly for re-releases of older titles. That's when the Blue Train reissue comes out in Japan. As we read in the label’s monograph, Lundvall was an experienced producer, working at Columbia Records in the 1950s, and from 1976 as the head of CBS Records.

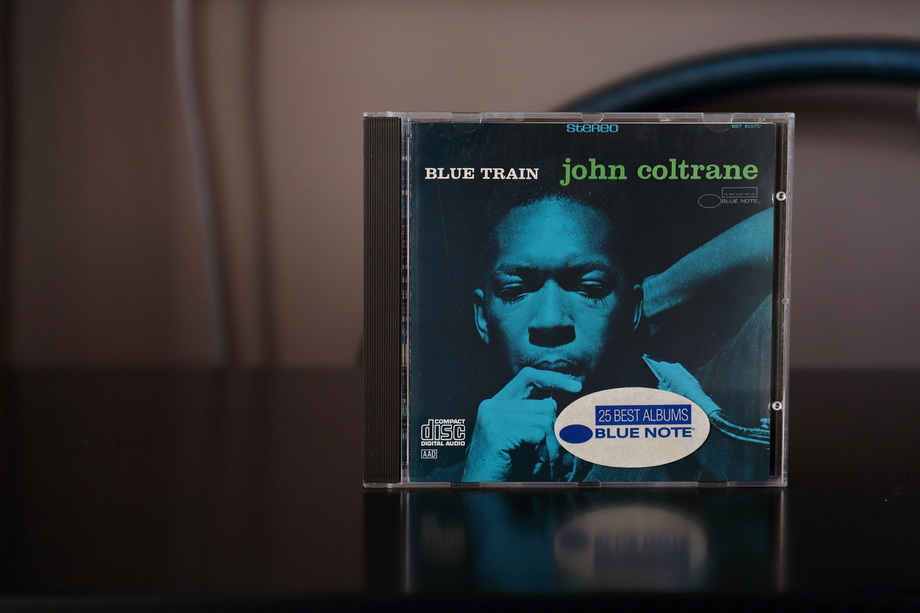

1985

A year later, the CD version, which we show below, was released by the newly established EMI Manhattan Records. It has been released in the US and other countries. We will not find information about the remaster in it. It is only known that almost certainly the signal from the master tapes was recorded using 16-bit (44.1kHz) converters, because they were the standard in studios at the time, and recorded on a U-matic mastering tape. Hence, next to the Compact Disc logotype on the 1985 version, we will also find the SPARS A|A|D marking on it (more about SPARS codes HERE). It was an analog remaster, although the Japanese version, a year older, was improved digitally, probably using the 16-bit JVC system, which was also used to prepare the material for the K2 discs.

This album was released as part of the "25 Best Albums Blue Note" series and in the album's booklet, unfortunately of low quality, we received a folded poster on which the titles released at that time were distinguished. A sticker with the logo of the series was applied to the box. The European version was pressed in the Dutch Philips factory, while the American version was pressed in Japan. It was a stereo version.

1991

In the following years, single reissues were released, using the remaster from 1985. It was not until May 1991 that the first remaster of this material was prepared for CD. This work was done by a specialist brand, Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab, as part of the "Original Master Recording" series. The transfer from the master tape was made at the company's headquarters, and the work was done using tube devices. At that time, MoFi was still releasing CDs on gold, in patented cases - and that was the case here. Part of the edition was pressed in the Japanese Sanyo pressing plant, and part in the USA—we are reviewing the latter version.

1996

With the development of technology, the parameters of analog-to-digital converters improved. Blue Note, as well as other labels, on the occasion of each major innovation, decided to copy the signal from the tape using the best devices at the time. In 1996, a new remaster was released in Japan, made using 20-bit converters, working with a sampling frequency of 88.2kHz. There is even an appropriate logo on the obi.

Interestingly, a year later a US version was released, also mastered with 20-bit converters, in the SBM technique; Ron McMaster was responsible for the master. The cover reads "The Ultimate Blue Train" and the CD features - for the first time—two alternative takes of the tracks on the album and a CD-ROM section featuring an interview with Van Gelder and a short video of Coltrane and Davis.

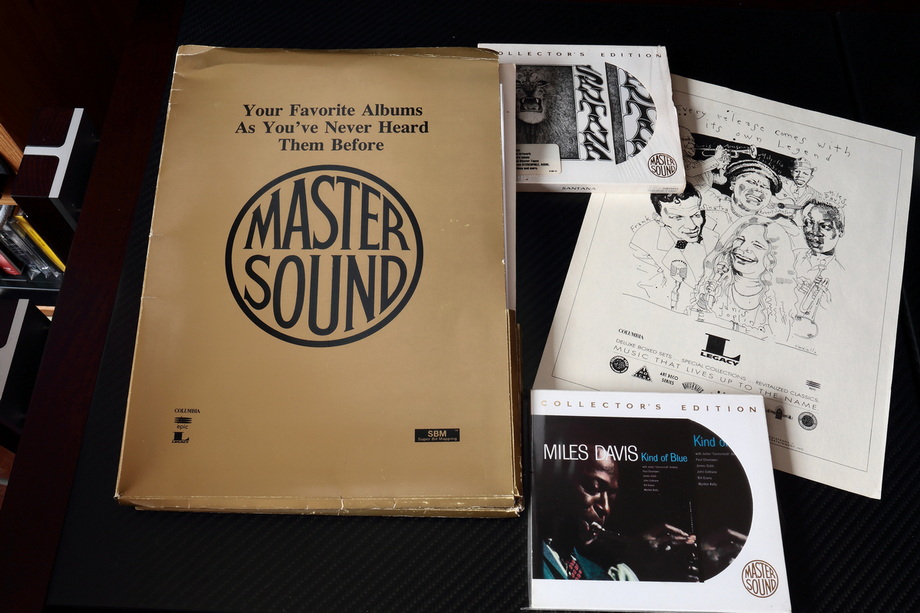

Super Bit Mapping

Sony used SBM for re-issues from "Master Sound" series

SBM is an abbreviation for "super bit mapping," a proprietary technique developed by Sony. The SBM was presented at the 93rd AES Convention in San Francisco in 1992. It was about the re-quantization process, in which the recorded 20-bit signal was converted to the 16-bit signal required by CDs.

At that time, A/D converters with a resolution of 20 bits were already available. Recording the signal in this form resulted in higher dynamics and lower noise. The problem was that the CD required a 16-bit signal, and its conversion was not easy, because it resulted in the so-called quantization noise. To get rid of it, the SBM processor moved it above 15kHz, where it was not so audible and where it could be filtered out. This signal was fully compatible with the CD technique, so no additional decoders were needed for reading.

The 1997 release is noteworthy in that the version entitled The Ultimate Blue Train for the first time added to the basic set of five tracks two alternative takes: Blue Train ( Alternate Take) and Lazy Bird (Alternate Take). These tracks have been remastered by Van Gelder and will appear on almost all subsequent releases for many years to come.

1998

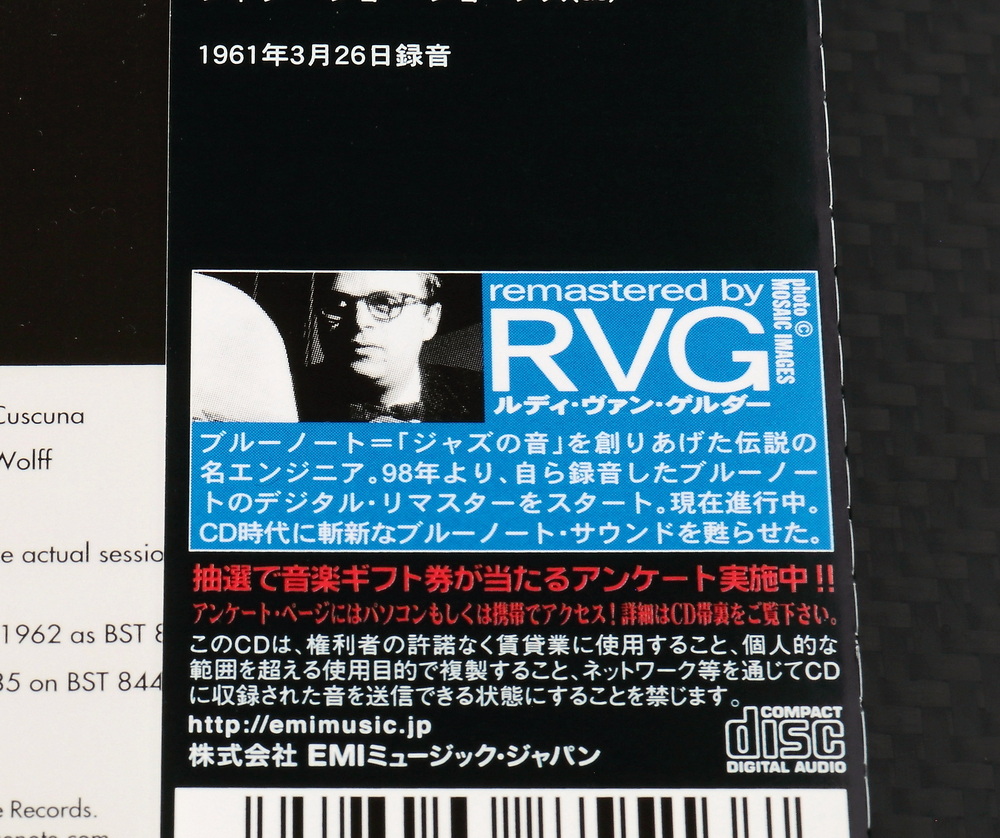

In 1998, on the initiative of Hiroshi Namekata, head of the Toshiba-EMI label, the process of digital remastering of recordings by RVG began. As he told Mix magazine, "everything was under his control." He used 24-bit A/D converters (96kHz). In Japan, these discs were released as mini LPs, and in other countries, since 1999, in plastic cases:

Since the CD came out, other people have been transferring and mastering the sessions that I recorded for Blue Note, but something was missing in them. It's not a matter of high or low quality; it's about my approach to music. Because I was there and still remember clearly what the musicians and producers were trying to achieve, I feel that I can transfer these experiences to the mastering process. I would like to emphasize that this is not a question of good or bad, I am simply a messenger.

In 1998, as many as 250 titles remastered by him were released in Japan, and a year later selected ones were also released in the USA and Europe. In 2003, RVG prepared another 100 titles for the Japanese market, and a year and two years later, several dozen more (more HERE).

The 1998 remaster was accompanied by a large promotional campaign, and the discs with the initials RVG were collected in a special box. The mini LP version that was released in Japan bore a large inscription "Blue Note 24-bit by RVG" on the obi, and the initials of the sound engineer also appeared on the CD itself. It was a repetition of Van Gelder's act of signing LP masters in this way—it was a very characteristic thing for him.

2003is the year the material was released in Europe. There is no certainty, but it seems that it was a new remaster of monophonic material, as we read in the booklet: a "24-bit" one, made by RVG. However, we do not know with what sampling frequency the signal was recorded from the tape—I assume 96kHz. The album was released not on Compact Disc, but on Copy Controlled Disc.

Copy Controlled Disc

The picture shows examples of CCD releases. They could not bear the Compact Disc logo and had to be marked with a special logo and a warning about incompatibility with computer drives

As we wrote in an article from January 2017 (see HERE), the anti-piracy hysteria peaked in the early 2000s. Publishers did their best to make it difficult to copy CDs to other digital media. This was one of the reasons DAT tape was never widely accepted. The intentions were good, after all, it was about securing the copyrights of labels and artists. However, it changed the rules of the game - before, you could have copied music to cassette tapes and no one saw a problem with it. Very quickly, in response to these safeguards, algorithms were developed that allowed copying discs without any problems, e.g. in the Nero program.

Midbar Technologies, the company responsible for probably the best-known method of protecting CDs, came from Israel. It has developed a security system known as Cactus Data Shield (CDS). In the years 2001 - 2006, EMI Group and Sony on selected markets (Europe, Canada, USA, Australia) issued CDs bearing a characteristic logo - the letter "C" in a circle. CDS was a highly invasive technique. It interfered with disc playback in two ways, including modifying the audio signal itself (Data Corruption). Deliberately introduced distortions resulted in the CD transport having to interpolate the lost data, thus degrading the sound quality.

In parallel with the CCD, a hybrid Super Audio CD was released in the US, and it was the first time we received material from Blue Train in high definition. The entry in the booklet says that both layers were remastered by Rudy Van Gelder. There is no word anywhere about whether it was a 24/96 transfer to the DSD domain or a remaster to DSD directly from the master tape. Knowing life, however, I would bet on the former.

An interesting feature of the 2003 editions is that for the first time details of the piano solo from the title track are given. As we read in the monograph entitled Blue Note – Uncompromising Expression, Blue Note edited the "master" tapes very heavily. So they did also this time. The piano solo is identical in both takes and, as it turns out, comes from the alternative version, recorded just before the one we know. Van Gelder pasted it in the place from which he had cut his other version. The original cut solo was not found at the time.

2008

The following years also saw reissues of Blue Train. They were based on the 2003 remaster, but were released on "regular" CDs, and in Japan, in 2013, on SHM-CD. An important event was the release of a completely new, analog remaster. It was prepared by an American company Analogue Productions and was released on a hybrid SACD. Kevin Gray and Steve Hoffman working under the aegis of AcousTech Mastering studio were responsible for the master. This studio used tube devices and modified reel-to-reel tape recorders.

2016

In 2016 and 2017, the most technically advanced editions of Blue Train are released in Japan on Compact Disc in forms of SHM-CD, Platinum SHM-CD (2016) and UHQCD (2017).

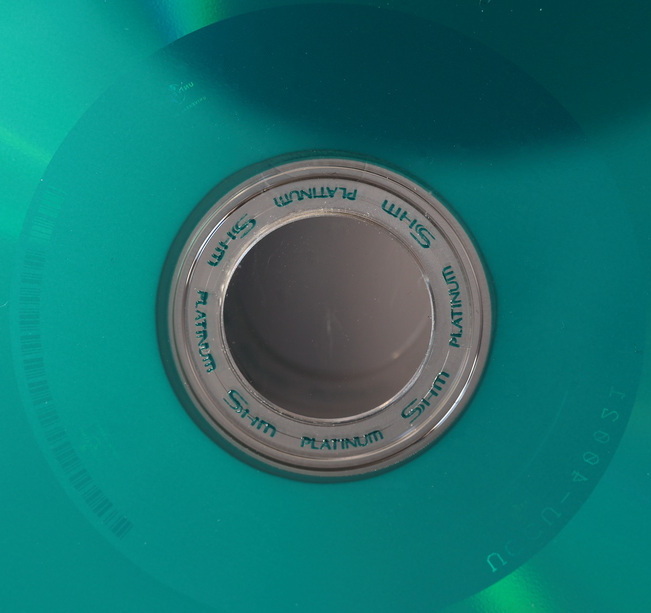

PLATINUM SHM-CD

Platinum SHM-CD and SHM-SACD discs are coated with a special turquoise paint to minimize reading errors

SHM-CDs (Super High Material CDs) appeared on the market in the second half of 2008. There are two companies behind it: JVC and Universal Music Japan. Classic CDs are made of transparent polycarbonate (a type of plastic). However, this plastic is not perfectly transparent, so the laser beam is refracted and weakened in the disc, which forces the reading system to work harder, generating higher noise.

For the production of SHM-CDs, a material (plastic) originally developed for LCD displays is used, which is characterized by much higher permeability. This means that the laser beam returns to the optical element in a more precise way.

The monophonic reissue of the Platinum SHM-CD from 2016 was released in Japan in an extremely scrupulous way. The cover has been rendered superbly, with a varnished front and a matte back, as in the original LP pressing. The disc was packed in rice paper with a foil insert. It is important that it was the first remaster in years made not by RVG—unfortunately, it is not known by whom (this is the year in which Van Gelder dies). What's more, the signal was transferred from the "master" tape in the form of 24/192 files. It seems that the new master was made much earlier, in 2011, for the reissue of the LP.

Platinum SHM-CDs are Compact Discs, but pressed in a different way than ordinary CDs. Instead of aluminum, an alloy of silver and platinum is vapor-deposited, and instead of ordinary plastic, the plastic used for the production of LCD displays is used - much more transparent and homogeneous. The paint color is also special, minimizing light refraction. And there is something else. In a classic press, the material is delivered in the form of 16/44.1 and a glass matrix is burned from this signal. The Master for Platinum SHM-CD is prepared from 24-bit, 176.4kHz files, converted "on the fly" to the values required by the CD. This technique is called HR Cutting.

2007

On the 60th anniversary of Blue Train release in Japan, and only in Japan, the SHM-SACD is released. The signal for it was transferred from the "master" tape to DSD. It is not known whether the copy was made by Kevin Gray and whether it is the same material as in the 2003 version, but we do know the name of the person responsible for the project on the publisher's side—Onsho Shiyou. SHM-SACD is a single layer SACD. The disc is made of the same plastic as SHM-CDs, with a turquoise-colored varnish, as on Platinum SHM-CDs.

2018

In 2018, the Japanese branch of the Universal Classics & Jazz record label offered another hi-res version, this time on UHQCD + MQA discs. The obi says that this material comes from a DSD transfer made in 2017 for the SHM-SACD disc. The DSD signal was transcoded to PCM 24/176.4 and encoded in MQA. We associate this abbreviation with the Tidal streaming service, but you can also save the signal on a CD in this way.

As we wrote in the article MQA + UHQCD: Hi-Res Compact Disc on May 23rd 2018, CD JAPAN, Japan's largest online retailer specializing in physical disc releases, has announced the launch of a new type of optical disc that looks like a Compact Disc but with a modified signal, called Hi-Res CD (more HERE).

Examples of discs with MQA signal: Japanese UHQCD + MQA sampler as well as MQA-CD and Pure Audio BD with an additional SACD/MQA-CD released by the Norwegian label L2

Physically, it is a UHQCD, a CD made of three layers: a photopolymer, a metal reflective layer and a transparent protective layer. On top, the disc can be covered with varnish with information about the given title. These discs are read by a classic red laser. Photopolymer is a material that turns solid under the influence of irradiation in an ultra-fast way (more HERE).

However, it is not a Compact Disc and cannot be marked with the appropriate logotype. The signal on the UHQCD disc was encoded in MQA. Master Quality Authenticated is a technique owned by Meridian Audio and presented in 2014 by its founder, Mr. Bob Stuart. It was created from the need for streaming, i.e. sending and listening to high-resolution files in real time.

Let's compare: a 24/192 file requires a bandwidth of 9.2 mbps, and when packed in MQA only 922 kbps. Thanks to this, you can transfer hi-res files in real time even with low internet bandwidth. But they also managed to fit the hi-res signal on a CD. The downside is that MQA is a lossy format. The basic 24/48 signal is lossless, but higher sampling rates are lossy. To decode the disc, you need a player with an MQA decoder or a CD transport and a D/A converter that decodes MQA on all inputs, not just USB. If we play this disc without a decoder, it is read like a regular Compact Disc.

2022

The 65th anniversary of the release of the album could not do without a new remaster, this time as part of the "Tone Poet" series. For the first time the MONO and stereo versions were remastered simultaneously. What's more, for the first time the stereo version was released with seven bonus tracks, none of which had previously been released on vinyl, and four of them in no format at all. This version is officially titled Blue Train: The Complete Masters.

Blue Note entrusted it to Joe Harley and—again—Kevin Gray, who had previously, in 2014, made a master for the LP release in the "Music Matters" series. This is an analog remaster, made using tube and transistor equipment in Kevin's studio. The same track was used to cut the varnish for vinyl records and DSD files. As the gentlemen say in the video interview this is the "definitive" version for them (more HERE).

Japanese reissues of RVG remastered discs from 2008 and 2009

In an interview with Stereophile magazine, Harley said that the tapes are still in excellent condition. He adds that from the 1950s to around 1964-65, Rudy used Scotch 111 acetate tapes. No one today knows exactly what went into it, but it gave an incredibly durable surface:

We always joke that there's whale oil in there or something. Whatever it is, they made this component illegal sometime in the 1960s, so it was probably not very healthy. But [the tapes] are tough, really tough. We fired up the master tapes and they sounded like they were recorded yesterday. (Bard)

Picking up the tapes—as they say—in gloves, they did not look at the notes they made in 2014, during the last remaster. Eight years have passed since then, during which Gray's mastering system has changed a bit, and their approach to the material has also changed. Harley mentions that they only made "small moves," interfering with the material more gently than before. Major changes only occurred in the treble and bass:

What Rudy did was very consistent. He minimized the low bass because [the label] had to keep selling those albums. They didn't want returns, so the releases had to play on anything. In the 1950s, that meant all the devices on the market. The bar was set very low. He also used compression. Many of his notes speak of an eight-to-one ratio, but still nothing like modern rock or pop where everything is just cut off. He used compression to add some kind of excitement to the presentation. My goal was to convey everything that is on the tape. How did they record it? What did they play and what did they listen to, and what was finally on the master? (ibid.)

Both albums were released on LP, Compact Disc, and in Japan additionally on UHQCD and SHM-SACD. All versions used the same remaster. The original tapes were played on a tape recorder, and the signal went through the mastering system and then split up. Remaining in the analog domain, the varnish was cut, and after passing through the A/D converter, the DSD version was created, which was then used to make SACD, CD and UHQCD discs. Unfortunately, it is not known whether it was DSD64 or denser format.

It's a shame the digital versions weren't released as a 7" mini LP—it was the perfect opportunity to celebrate this brilliant album in the best possible way.

Summary

As you can see, the way in which the Blue Train was remastered was a direct reflection of the technical capabilities—both on the side of the studio and the pressing plant. The corrections concerned the word length and sampling frequency - from 16, through 20- to 24-bits and from 44.1, through 96 and 192, up to DSD. The big change was the arrival of SACD and these versions are usually better.

But the way in which discs are pressed has almost undergone a revolution. The first signal that something was changing was the choice of Mobile Fidelity - instead of an aluminum layer, a gold layer was used. The HQCD discs changed it to an alloy with the addition of silver, and the Platinum SHM-CD additionally with platinum. Changing from ordinary plastic to a higher class ones—HQCD, SHM and Platinum SHM-CD, or to a double layer—UHQCD—was the next step to improving the process of reading the data. An important change was covering discs with turquoise paint and burning the matrix directly from hi-res files.

The most important, however, seems to be the approach of the mastering engineers. As you will see in the third part of the article, in which we describe the sound of individual releases, the most important are the people and the equipment used to work on the material. That is why the versions prepared on tube devices by Kevin Gray sound best. But more on that in the next part.

Bibliography

Ashley Kahn, The House That Trane Built: The Story of Impulse Records, W. W. Norton & Company, New York 2007.

Ashley Kahn, A Love Supreme: The Story of John Coltrane's Signature Album, Penguin Books, London 2003

Lewis Porter, Chris Devito, David Wild The John Coltrane Reference, Routledge, Abingdon 2013.

Havers Richard, Blue Note: Uncompromising Expression, Thames & Hudson, London 2014.

RVG Legacy. Preserving the Legacy of Rudy Van Gelder, RVGLEGACY.org, accessed: 2.02.2023.

Impulse 60! Collector’s Zine, red. Barbie Bertisch & Paul Rafaelle, 2022.

Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, NJ - Virtual Tour, www.YOUTUBE.com, accessed: 2.02.2023.

Robert Baird, Revinylization #35: John Coltrane's Blue Train Remastered (Twice) for Tone Poet, Stereophile, 2 Nov 2022, www.stereophile.com

Bert Caldwell, Simply Jazz with legend Rudy Van Gelder, YouTube 1994, www.YOUTUBE.com, accessed: 2.02.2023.

Jeff Forlenza, Rudy Van Gelder: Jazz’s master engineer, Mix 254, 10.1993, p. 54-64.

D. Sicker, M. Sickler K. Kimery, Rudy Van Gelder: NEA Jazz Master, Smithsonian National Museum of American History, 5th Nov 2011, AMHISTORY.si.edu, accessed: 2.02.2023.

Dan Skea, Rudy Van Gelder in Hackensack: Defining the Jazz Sound in the 1950s, „Current Musicology" No. 71-73, 2002, journals.library.COLUMBIA.edu, accessed: 2.03.2023.

Sasha Zand, Rudy Van Gelder: Recording Coltrane, Miles, Monk, etc., “Tape Op", Jan/Feb 2023, TAPEOP.com accessed: 2.02.2023.

SACD Blue Train releases: 2003 SACD/CD (right upper corner), 2008 SACD/CD, 2017 SHM-SACD, 2022 SHM-SACD

W. Clark, J. Cogan, Temples of Sound: Inside the Great Recording Studios, Chronicle Books, San Francisco 2003.

Dave Denyer: The Reel-to-Reel Rambler, THEREELTOREELRAMBLER.com, accessed: 2.02.2023.

Peter Martland, Since Record Begin: EMI, The First 100 Years, Batsford, London 1997.

Howard Massey, The Great British Recording Studios

Howard Massey, Behind the Glass Volume 1: Top Record Producers Tell how They Craft the Hits,

John Pickfort, Vintage: EMT 140S Plate Reverb, MusicTech, 28th May 2014 , MUSICTECH.com, accessed: 2.02.2023.

Recording label: Blue Note Records

USA

text WOJCIECH PACUŁA

images High Fidelity