How do you spell diva? Barbra Streisand has been a brash, larger-than-life, irrepressible talent throughout her career, whether on Broadway, the big screen, or in the recording studio. Her amazing voice, her physical presence on stage and in front of the camera, and her prowess behind the microphone has helped win her an astonishing array of professional awards. She's one of the handful of people in entertainment to have achieved an EGOT (wins for Emmy [5], Grammy [10], Oscar [2], and Tony [1] awards); she also has won four Peabody awards for excellence in multimedia. A slew of awards and nominations have come from just about every corner of the planet. Early in her career, Columbia Records president Goddard Lieberson (Columbia employees jokingly referred to him as "God") initially resisted signing her to the label; he thought she was just another cabaret singer of the sort he personally abhorred. Lieberson eventually relented and offered her a contract in 1962, but Barbra ultimately held out for complete artistic control over her material—pretty cheeky for a relatively unproven artist at the time!

So, let me ask again, how do you spell diva? Why Barbra, of course!

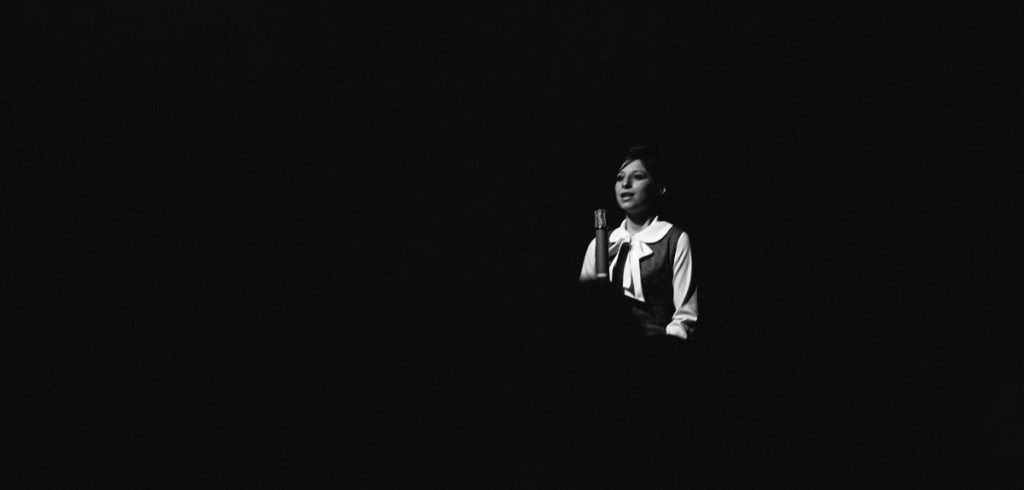

Greenwich Village, 1960

As an eighteen-year-old unknown in New York City, Barbra Streisand was trying to land elusive acting gigs on and off Broadway. While appearing in the very short-lived production The Insect Comedy, a fellow cast member who'd heard her singing encouraged her to enter a weekly contest at a local Greenwich Village club, the Lion. First prize was $50 and a free dinner, which was incentive enough to coax her into entering the competition. Barbra wowed the crowd with a passionate rendition of Harold Arlen's "A Sleepin' Bee," won the contest, and was offered an invitation to become a regular at the Lion. Whose manager was overwhelmed by her larger-than-life stage presence; after only a few performances, he suggested that she audition at the ritzy and much higher-profile Bon Soir club.

Barbra passed the audition; her sellout Bon Soir performances were generating so much excitement that she started getting notices in The New York Times and other NYC papers. During a second extended run, Barbra made one of the most important business connections of her entire career when talent impresario Marty Erlichman dropped in one night to find out what all the buzz was about. Mesmerized by Barbra's performance, he rushed backstage afterwards to offer his services, proclaiming that he had no doubt she'd go on to win awards in every performance category that existed. Erlichman was crushed to find out she already had a manager, but left his card and encouraged her to call him if she ever needed anything. Anything at all. Marty caught every one of her shows during that engagement.

While working the cabaret circuit, Barbra found herself in an intractable arrangement with a stubborn Detroit nightclub owner. Taking Marty Erlichman at his word, she called him collect in San Francisco to see if he could help resolve the problem; he promised her that he would. Marty then proceeded to reach into his own pocket to settle the matter, and when Barbra learned of his good deed, she immediately hired him as her manager. A mere handshake sealed the deal; a simple act of faith forged a working relationship that has lasted sixty-plus years.

Barbra Streisand Live at the Bon Soir: Prelude

When Goddard Lieberson finally came to his senses and Barbra inked the Columbia contract, it was decided that her debut album would be a live recording at the Bon Soir, the location associated with her most dynamic performances. Columbia secured the Bon Soir for three nights, November 5-7, 1962, and on the morning of the 5th, Columbia's house engineers Ad "Pappy" Theroux and Roy Halee arrived at the club to set up the microphones and recording equipment. The original live recordings at the Bon Soir were done using an Ampex 350-3, 3-track, ½ inch, vacuum tube analog open reel recorder. Capturing Barbra's live performances at the Bon Soir might prove to be a challenge for the Columbia team, as only a couple of recordings had ever been made there, but Theroux and Halee were confident they'd get the job done.

Barbra had chosen 24 songs for the three-day event, and her plan was to mix-and-match them on each evening to provide some variety to the sessions. She chose an eclectic mix of somewhat unlikely songs from the likes of Lenny Bernstein, Tom Jones, Harold Arlen, Oscar Hammerstein, Cole Porter, and Rodgers and Hart, among others. And she made it clear from the get-go that she wasn't interested in singing only standards. Streisand was accompanied by a quartet of crack musicians, featuring Tiger Haynes on guitar, Averill Pollard playing acoustic bass, John Cresci on the drum kit, and Peter Daniels was behind the piano. Barbra shared an excellent rapport with her backing musicians, was in excellent voice on all three nights, and played the room like a seasoned professional. By all accounts, the live performances and the recordings they generated were going to be a smashing success!

Barbra, onstage at the Bon Soir.

At least, until Barbra, Marty Erlichman, and the label execs at Columbia Records listened to the tapes, where everyone present felt Barbra's passionate performances and the electricity of the Bon Soir atmosphere just wasn't properly captured by the recordings. A lot of second-guessing went on between the engineers and Columbia's promotion people, but the mixing technology just didn't exist at the time to try and salvage the tapes. After being deemed unacceptable by Columbia, the live tapes were shelved.

At that point, in January, 1963, Columbia moved on with plan B, which was to record Barbra in the studio for her debut release. For the studio recordings, Barbra chose twelve of the songs that she performed at the Bon Soir engagements (one song, "Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered" was cut from the final album release). But this time, the studio got heavily involved in the album's arrangements, and even included an orchestra with strings on many of the tunes and horns on others. Regardless of whether the album was totally true to Barbra's original artistic vision, The Barbra Streisand Album was a critical and commercial triumph. Peaking at Number 8 on the Billboard Charts for 1963, while reaching Gold record sales status in the US and Platinum sales status worldwide. And eventually won three Grammy Awards in the categories of Album of the Year, Best Female Vocal Performance, and Best Album Cover (the shot used for the album cover actually came from the Bon Soir performances). So…tragedy was ultimately and triumphantly averted, but with regards to the live recordings (which spent almost six decades languishing in Barbra's vault), oh, what might have been!

Barbra Streisand Live at the Bon Soir on SACD from Impex Records and Columbia/Legacy Recordings

To celebrate the 60th anniversary of Barbra Streisand's relationship with Columbia Records, it was decided a couple of years ago that the original Bon Soir live recordings would be finally released. Despite the obvious sentimental reasons for the release, it's also an album of tremendous historical significance, and the only one that exists that captures Barbra in her youthful prime, live on the stage. And the recordings of those three nights in November, 1962 contain twenty-four unique songs that have virtually never seen the light of day—only a few of the songs have ever been included as bonus tracks or in box set releases.

Prior to its release, the original master tapes for Barbra Streisand Live at the Bon Soir were inspected and found to be in decent shape to proceed with—but the same problems that prevented their release in 1962 were just as glaring nearly six decades later. In the original microphone and mix setup for the Bon Soir recordings, several problems existed. Roy Halee and Pappy Theroux weren't able to completely overcome the Bon Soir's less than stellar acoustics, so they attempted to still get a good recording by only using three total microphones in the process. One microphone for Barbra's vocals, and the two remaining mikes were split between the quartet of instruments, with a very left/right perspective, which was very commonplace for the day. At some point in the process, whether at the recording and mixing console, or from the actual microphone feeds, leakage between the instrument mikes and Barbra's vocal mike occurred. That made it impossible (especially in 1962, and still exceptionally problematic today) to compensate for in the final mix for album release—you couldn't control the level of Barbra's vocals without affecting the other instruments, and vice-versa. Those anomalies help explain the lackluster sound of the original tapes, and were the primary reason the recordings were shelved for so very long.

Barbra Streisand backstage at the Bon Soir with composer Harold Arlen.

Grammy winning mix engineer Jochem van der Saag was enlisted to remix the original tapes for the 60th anniversary release; album co-producers Barbra Streisand, Marty Erlichman, and Jay Landers accompanied him at every point of the process. van der Saag decided that a radical approach was necessary to achieve the desired result of isolating and remixing the instrumental and vocal tracks, while preserving the acoustic of the Bon Soir. The 3-track master tapes were transferred to high resolution, 24-bit/96 kHz digital files, one for each of the three tracks. Jochem van der Saag then worked closely with both Barbra and her long-time producer, Jay Landers, to create the new stereo mixes. All digital mixing and audio restoration work was done at 24/96, using cutting edge Spectral editing technology throughout the grueling, months-long editing process. And van der Saag also managed to create a more modern instrumental spread on the new mixes, without the typical hard-left/hard-right spread found in so many recordings of the era. At the same time, he was able to completely isolate Barbra's vocals and present them front and center in the mix.

The 24/96 final stereo mixes were then sent to mastering engineer Paul Blakemore. He knew that the final release would be issued in multiple digital formats as well as on 180 gram LP records, so the mastering work was done with those multiple formats in mind. Blakemore felt the mixes would benefit from a small amount of parallel compression, which is a process that mixes a compressed audio signal with the original uncompressed signal to achieve a slightly greater overall loudness. And helps to bring low-level musical details to the forefront, without the audible artifacts typically associated with dynamic range compression. An all-analog signal processing path was used throughout the process, and that imbued the resultant mixes with an additional level of sonic warmth. The digital stereo mixes were then converted back to analog using Swiss-made, Merging Horus digital to analog converters. The analog signal was then routed into a Maselec MTC-2 mastering console manufactured in the UK. The compressed dynamic-range audio was made using a German-made, all discrete, class-A, solid-state compressor from Elysia Alpha Mastering. The compressed and non-compressed signals were then combined using the Maselec console. The resulting analog signal was then converted back into 24/96 digital using Merging Horus analog to digital converters. The record levels into the analog to digital converters were carefully optimized so that no limiting was required.

Upon hearing the first version of the mastering work, Barbra Streisand decided to make some subtle mix adjustments, and the mastering process was repeated using the same settings. Conversions to formats like CD audio and standard resolution digital streaming were done using the Swiss-made, Pyramix digital audio workstation utilizing their proprietary apodizing filter system. Paul Blakemore has stated that the Pyramix digital conversion system is considered by audio engineers to be the most transparent digital conversion system that currently exists, and is the finest he's heard in his 40 years in the business.

Barbra Streisand with Columbia's David Kapralik, who served as the emcee at the Bon Soir concerts.

This performance is incredibly entertaining; remember my comments about Barbra epitomizing the definition of the word diva? In the album's opening track, Columbia's Dave Kapralik is making his introduction, when he mispronounces Barbra's last name; she immediately steps to the mike to correct his indiscretion! Who else at that point in time—especially as a twenty-year-old—would have been so bold! I won't give you a blow-by-blow rundown, but this is a disc of many highlights that easily outshine their studio album counterparts as heard on The Barbra Streisand Album. The studio versions are great, but are lacking the spontaneity and fearlessness that the live recordings are literally brimming with.

The newly remastered 60th anniversary release of Barbra Streisand Live at the Bon Soir was released on November 4, 2022 as both digital downloads and compact discs—the date coincides almost to the day with the dates of the original recordings six decades earlier. Mastering for 180 gram LPs and SACD was done by Bernie Grundman at Bernie Grundman Mastering in Hollywood. DSD authoring was handled by Gus Skinas at the Super Audio Center in Boulder, Colorado.

By special agreement with Columbia and Sony Legacy, all LPs and hybrid stereo SACDs are being produced by Impex Records. The 33 RPM, 180 gram LPs will arrive late Spring/early Summer, and the SACDs have been available since December, 2022. The SACD that I received for review shows the excellence that Impex puts into all their releases in spades; the case-bound packaging is superb (Barbra's designer Gabrielle Raumberger was responsible for the package's gorgeous aesthetic), and the bound-in booklet is filled with plenty of photos of Barbra at the Bon Soir. And the absolute icing comes in the form of the excellent and entertaining liner notes from Barbra's long-time producer (and co-producer of this release) Jay Landers, which really bring the events surrounding the realization of the important Bon Soir recordings to life for the reader.

Listening Results

If you click on my name in the header above, you can see descriptions of the two systems I use for evaluation of all music titles and equipment reviews. As I noted above, this album dates from the early sixties, and the recording values of that era were very left-right in the early days of stereo recordings. Meaning, essentially, that many recordings of that vintage feature sound that's panned very hard to the left and right channels, often with very little information in the center. Jochem van der Saag was able to make mixing compensations to correct for that, and there's a much better instrumental spread on the remastered album.

I generally rip any SACDs to .dsf files for native DSD playback on my digital music server system. On my digital system that features the Magneplanar loudspeakers, with the .dsf rip of this excellent SACD played back in native DSD, the sound quality was superb. Barbra's vocals floated both between and behind the loudspeakers with near-holographic imaging. And while this is essentially a historical recording, the magic provided by Jochem van der Saag, Paul Blakemore, and Bernie Grundman has taken the sound quality to a level that comes very close to approaching that of many audiophile recordings. This recording isn't by any stretch of the imagination perfect, but I'm absolutely certain that if compared to the original tapes the sound quality is miles beyond them. Barbra's all-important vocals are nearly perfect, and for this recording—that's good enough.

I also played the physical SACD disc on my mostly analog system with its complement of all-tube amplification and the KLH Model Five loudspeakers. On this very vintage-sounding system, this very vintage recording was rendered with superb fidelity. When the source material is as great as Barbra's performance here, you'd probably get almost as much enjoyment from it if you listened through a transistor radio!

From the moment I received this SACD disc, something jumped out at me in the technical description: "Mastered for SACD at 24-bit/96kHz." For those of us who believe that SACDs and native DSD are the highest art form for recorded digital media, "Mastered for SACD at 24-bit/96kHz" seems totally counter-intuitive. But for this project, that description strikes me as an oversimplification of the transfer process, which employed a significant level of advanced digital and analog technology. That said, I don't think you should allow the 24/96 PCM transfer that was required by Jochem van der Saal and Paul Blakemore to damn any high-end aspirations by this album. Even though there's a prevailing trend among digital music enthusiasts and audiophiles that 24/96 is the absolute minimum threshold for a music file's acceptability as a viably high resolution playback medium. My personal music server is filled with compact disc-quality rips, SACD rips to native DSD, DSD downloads, BluRay and DVD-Audio rips to 24/96, and plenty of high resolution PCM downloads (that vary from 24/96, 24/192, and 32/384). Many of the files that I get the most musical enjoyment from are my 24/96 rips of Steven Wilson's excellent remix/remasters of prog and rock titles.

As part of the listening and evaluation process of Barbra Streisand at the Bon Soir, I first listened to either my DSD rips of the physical SACD, or the actual disc, depending on the system currently in use. Then—basically for giggles—I listened to the 24/96 files available for streaming over the digital system using my Qobuz account. With the SACD being mastered from a 24/96 master, I expected that the Qobuz files and my DSD files would sound very similar in nature. Nothing could have been further from the truth—the DSD files always, always trumped the Qobuz 24/96 files, sounding more lifelike, more dynamic, more musical, and with a more solid stereo image. The realism of Barbra Streisand singing before me was so much more well defined when listening to the DSD files than with the 24/96 Qobuz files—I was absolutely astonished by the improvement. There are digital-to-analog converters (DACs) as well as software suites that upconvert PCM to DSD, and many audiophiles rave about the improvement in sound quality. I can only suppose that something of the same measure happened here when the 24/96 PCM master was authored to DSD by Gus Skinas at the Super Audio Center. And Paul Blakemore's predominantly analog mastering process didn't hurt either!

Conclusion

I don't think it can be denied that Barbra Streisand is one of the most important performers of this or any generation, and whose resume ticks every box for every major performance medium. Barbra Streisand Live at the Bon Soir captures her youthful exuberance at her brashest and best, and it's absolutely astonishing that it's taken sixty years for these remarkable performances to see the light of day. Highly recommended!

Barbra Streisand: Barbra Streisand Live at the Bon Soir: Stereo Hybrid SACD, $34.99 MSRP.

Barbra Streisand

Impex Records

All photos courtesy of Impex Records and Columbia/Sony Legacy