In the past several years, I've been simply stunned by the sound quality of vintage recordings released by HDTT that credit the audio restoration work by John Haley, founder of Harmony Restorations, LLC. In many cases, such as the recent release by HDTT of the Judy Garland The Greatest Night In Show Business History (see my review HERE), the sound quality has far surpassed that of any release I've heard previously. Similarly excellent have been the superb restorations of recordings by cellist Nathaniel Rosen (see reviews HERE and HERE).

The results are as if John has some special magic pixie dust, some secrets of the craft that few others apply. So, as might any dedicated audiophile who loves great sound, I emailed John to ask if we might have a conversation about the restoration work he does. Here is that conversation...

Rushton Paul: Please tell us a bit about your background and your tape restoration work.

John Haley: I've been doing this restoration work for many years. I was a practicing lawyer for years, but doing restoration work is something I've always enjoyed doing on the side. With my retirement from practicing law, I've now been doing restoration work full time for a number of years. Harmony Restorations is my company and and I work as an independent contractor for several clients, including Bob Witrak’s company High Definition Tape Transfers (HDTT).

I have a music degree with a concentration in voice and piano. I read music well and I've always been a musician, and that has been incredibly helpful to me with the restoration work. I'm very often working with the score in hand, and I can't imagine doing this work without being able to read music.

I also have a good ear—I can tell if the second oboe is out of tune and that kind of thing. And I can also correct many musical issues. I've gotten pretty good at editing musical things, but it's a very different question as to whether I should be doing that or not—but I can. There are times when its fine to edit and times when it's not. I mean, people do want to hear exactly what note came out of Maria Callas' mouth, even though I could make it better. But that's something I won't do, I won't change that one.

So, how did you learn to do this restoration work

I've gotten very good at doing this just by just doing it. Everyone who does this same work is self-taught—there's no place you can go to learn how to do this restoration work at its most sophisticated levels. And, of course, we've grown up with the restoration programs which have changed drastically over the last fifteen years or so. What we can do with them today is vastly different than what we could do before. And, of course, there's a lot of acquired knowledge about formats and how to get the best results out of a source tape or record.

I think most people doing what I'm doing would agree that the most important thing is getting a good capture when you play back the source. Without that you're not much of anywhere. You must have a very good capture to get a super result.

It's been great working with Bob and HDTT because the focus is to get a superlative audio result, which with a lot of historical performance labels is not always true. Of course, Bob's company is built around an audiophile audience. There are a lot of collectors with a great interest in "hot items" but they are not audiophiles. But that’s okay, HDTT is happy to have them as customers. The moments where we can combine the amazing collector thing with the great sound thing, those are golden moments. That is always the hope.

It's challenging. I'm having a very good time with it. I'm doing this full time. Bob is too. We're cranking as hard as we can with it. My stove is overloaded with projects, but I'm plugging away on them.

How did you start working with Bob Witrak at HDTT?

I met Bob on a project about 6 years ago that did not come to fruition, but we became friendly. We weren't working together then, but I got to know what he did and he about what I did. The more we got to know each other, the more we realized how complementary our skill sets and backgrounds were. Bob has a fabulous technical background, largely self-taught. He has a tremendous understanding of what equipment to use. He has mastered that critical first step of getting the great capture from the source. He is also quite skilled at restoration. There are certain things that I do that he doesn't do. But, basically, we're both very up to date on what can be done. And we're friends.

I don't know anyone who can get a better capture from transferring a source tape than Bob. I can't. This is a tremendous skill he has. I hardly dub anything these days, because I want them to sound like Bob's dubs. So I make him do it.

Please tell us more about what got you interested in audio and reel-to-reel recordings specifically.

I can't remember any time I was not interested in audio, including all different formats other than cylinders. I've always been involved in tapes and records, and have always been interested in getting the best playback I can. I had a decent Sony tape recorder when I was in high school and loved it dearly. Reel-to-reel tapes sounded amazing to me, as compared to records, in those distant days.

To digress for a minute, I have an interest today in early digital tape formats. We have some quite valuable recordings in these nearly "lost" formats. A good many tapes from this era employed helical scan PCM recorded on video tape. Such video tapes could be Beta, VHS or a long defunct format known as U-matic. DAT tapes were also helical scan, as were Nagra D tapes, which recorded digital data on what looked like quarter inch audio tape. I used to have a U-matic machine that had hundreds of moving parts inside; I used to keep the top plate off so I could manipulate the innards with my fingers to get it to play—I eventually junked it. Such machines in working order are very rare today, as well as working Nagra D machines.

One HDTT release that you particularly enjoyed is the great American cellist Nathaniel Rosen's fantastic recordings of the Bach Suites for Solo Cello (HERE). This recording was made on a Nagra D recorder. It's really hard to find Nagra D machine today that actually works. The thing is quite heavy although it is only the size of a large bread box (to date myself). When new, such Nagra D recorders cost tens of thousands of dollars. Nagra D is an immensely complicated format, and in my opinion the recorder is basically a mechanical nightmare. Fortunately I was able to borrow two of these machines, one of which still works right, and I was able to dub the Nagra D master tapes for the Bach together with similar master tapes for several other of Nick Rosen's recordings that HDTT plans to release.

Regarding live recordings made on PCM video tape, once this kind of digital recording hit, a good many people stopped using analog tape and started using this early digital format, and eventually DAT tape. Virtually all such recordings were made at a 44.050, 44.1 or 48kHz sampling rate because that's what was available at the time. Some DAT machines also had 96kHz, but in my experience nobody used that.

This may be something that some audiophile customers don't want to hear, but there can be some real advantages in having original digital master recordings to work from, assuming you have a well-made recording to begin with. To start with, they have low noise compared to analog, so you have a lot more latitude to apply equalization to get the sound you want to achieve without pumping up the noise.

And we can often take the original digital data and transform it, digitally, into today’s digital formats without having to put it through any D to A conversion—allowing us to completely avoid the old D-to-A convertors from decades ago, with all their sonic limitations, as opposed to using today’s far better sounding DACs.

For example, in a recording like HDTT’s Rosen Bach Suites for Solo Cello, there is in fact NO D-to-A conversion involved at all until the listener applies it in his or her playback equipment—the listener can get a far better window onto what went on at the recording session this way. The disadvantage for audiophiles is that these recordings are not hi def. Still, there is some wonderful music in very clean sonics among these early digital tapes that I have here.

Can you talk more about working with the older analog tapes?

An explanation of the kinds of challenges presented by analog tapes generally involves one of two areas: what has to be done to bring them back to playable condition (for but one example, baking sticky-shed tapes), and what further may be needed to be done to improve their sound quality. Sometimes we can get a lot more music out of an old analog recording than one might think is there, using modern playback equipment and restoration techniques.

As I often say, there is no such thing as an old tape that doesn't need some work, and that holds true for master tapes. It seems that there are always physical issues. The notion that you're going to take an old master tape, drop it on your machine and get great playback is generally a myth.

For example, there are often old splices that are audible and can even fall apart during playback. Old tapes often have low frequency grumbly distortion on them, they stretch, they have pitch variability coming from a variety of causes, and they have noise that comes from the media itself. So you have to correct all this very carefully, so as not to damage the music. But you sure get a better result when you take care of such things, in particular removing the low frequency distortion that you often find on an old tape recording.

A good example would be the project I've done for HDTT: restoring Horenstein's wonderful live Das Lied von der Erde from Stockholm (HERE). That came from a very good sounding tape, but it was a noisy one. We took the noise out without damaging the music, and I had to remove a quite noticeable amount of low frequency distortion. But what a huge difference it made when I got the noise out. Suddenly the whole thing sprang to life without that overlay of tape noise that was coming from the media, not the recording.

Another example of a challenging restoration is the 1960 Dorati-led performance of Wagner's The Flying Dutchman (HERE), sourced from a reel-to-reel tape. That one had never been right before in any format. It was recorded in Walthamstow Town Hall in London by RCA's great Living Stereo recording team, Lewis Layton and Richard Mohr. RCA clearly brought their own recording equipment because there was 60 cycle hum in the recording—their recorders had to have been hooked up to power convertors (London-based recording equipment would have resulted in 50 cycle hum). But hum was the least of the challenges.

In that era, even the best commercial tape machines were not always reliable as to speed accuracy. Almost nothing in that recording was on pitch. It varied up and down as much as 3% (more than a quarter tone) and that's enough to seriously mess with the sound of the operatic voices. In places, the pitch errors made George London sound wobbly and made Leonie Rysanek flat, yet the chorus in the same scene could be sharp. As with any commercial opera recording, this was not recorded sequentially with everyone on the stage at the same time. It was done in pieces when people were available. So, like any other commercial operatic tape, it's chock full of splices.

We had a good source tape, and with Bob's great dub the basic sound quality was just magical. But the pitch fluctuation was driving me crazy—it was bouncing up and down and the singers were out of tune. So, I decided I needed to go through and put it all on pitch. There is a program called Capstan that is designed to do this, and it works pretty well, but it makes mistakes and requires careful review to check everything. So, for this project I decided to go through the entire recording a track at a time, correcting it by ear to get the pitch right. And so I got it all right on pitch. What a difference. It transformed the singers' voices. This recording had one of the greatest casts one could hope to find in this opera. Plus, the sound we got out of it allows you to really hear the Walthamstow venue, which is the reason they recorded so many operas there.

You've mentioned to me before some tapes that you've been able to salvage, such as the Desmar tapes. Can you tell us a bit more about these.

The Desmar tapes were originally made with great care, but were stored badly following the demise of the company. When restored, they sound marvelous. We only have two Desmar tapes featuring the great cellist Nathaniel Rosen, and the only one we've been able to release thus far is the Schumann cello pieces (HERE), which is a splendid recording. The other Desmar tape we have with Rosen is of the Chopin cello pieces, also recorded with the fine pianist Doris Stevenson. Of course, we plan to release it.

The Desmar tapes constitute a trove of very interesting stuff, released only on LP, although some of it was never released. There are two late Stokowski recordings: a performance of the Rachmaninoff Symphony No. 3 (which he premiered in the 1930s but never otherwise recorded), together with Stokowski's arrangement of the Rachmaninoff Vocalise as a filler. The other one is a selection of string works, including the Vaughan Williams Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis and the Dvorak Serenade.

The challenge with this entire trove as a whole is that hardly anything is labeled very well. For example, there is a stack of tapes labeled "BEAROAK" and nothing else. I think what they meant was "Baroque"—whether that was a joke, I don't know. But that's all there is. And, there seem to be multiple copies of the master tapes for some items. Virtually all the tapes need to be baked, making ID'ing some of them cumbersome. A few were covered in mold, but it's amazing how robust and salvageable tape can be. So far, so good with these tapes. I was very fortunate to be in the right place at the right time to avoid the entire Desmar master tape trove being thrown out, which was about to happen if I hadn’t grabbed it.

The Desmar catalog was a small one, only 25-30 releases. But there are a lot of wonderful things here which we are sorting through. And, I have a bunch of other similar small troves of salvaged tapes. Bob does, too. One batch of tapes we have are live recordings from a Copenhagen concert hall (the Falkoner Centret) where the hall manager, apparently surreptitiously, taped many live performances on good equipment. This includes the Judy Garland Final Concert From Copenhagen, from 1969 (HERE), as well as Maria Callas' live concert on June 9, 1963 (now released HERE). There is Paul Badura-Skoda in the very best recording of the Schumann Piano Concerto that I've ever heard (conducted by Rudolf Kempe), and a variety of front-rank classical singers and instrumentalists, plus a variety of jazz recordings. The range of performers they booked into that hall was large.

People just keep giving me stuff, as important tape collections keep coming available when collectors move on to that great collection in the sky. When I first got more serious about this restoration work professionally, I thought it would be hard to find projects worth doing. But that has not proved to be the case. Quite the opposite, it seems like a lifetime is not enough to do all the interesting projects that land at your feet. There is no shortage of great recordings that ought to be restored and released. One of the great things about releasing these recordings as downloads is that if the public just doesn't want something (whatever we may think of it), it hasn't cost us a lot other than our time. This lowers the risk level a lot, and we can be more adventurous.

What other projects do you have in the wings that you can talk about?

As mentioned earlier, we hope to release soon the Rosen Chopin cello recordings. Another recording which you have commented upon is Rosen's and Stevenson's lovely recording entitled Orientale (see LP listing on Discogs here), which is a compilation of especially beautiful shorter works for cello. John Marks, the producer of that album, has been very helpful in locating the the master tapes for us.

Yet another project, about which I've written in a blog post (HERE) for HDTT's website is the famous Jascha Horenstein performance of Mahler's Third Symphony with the London Symphony Orchestra. Many music lovers treasure the classic 1970 LP recording of this performance on the Unicorn label, recorded by famous audio engineer Bob Auger and his team. What is not well known is that a simultaneous four-channel recording, using totally different equipment and microphones, was made at the same recording sessions, at Unicorn's invitation, by the great American recording engineer Jerry Bruck. We have been given access to the half-inch, 15ips session tapes from that simultaneous recording, which HDTT will release once I've completed the restoration work. This will be a lot of work because the session tapes have never been edited down to a final edit master for release. Fortunately, we have Deryck Cooke’s notes from the Unicorn mixing sessions for most of it, but some of the editing must be done by comparing takes with the Unicorn recording, to be sure that what HDTT releases will be the same as what Maestro Horenstein approved.

With the blog post, I've included a "sneak preview" sample that is freely downloadable, so I encourage folks to take a listen. Kalman Rubinson, Music & Equipment Reviewer, commented after he listened to the sample: "I found it quite thrilling to hear this familiar recording as with new ears! It was just so much cleaner and more open. I noted that it had a much wider dynamic range than the original." I'm quite excited about this coming release.

I want to mention another exciting project that is in the works. That project is a brand new 5.0 channel 24 bit/192 kHz LPCM recording by leading audio engineer John Proffitt of a new reconstruction of Brahms’ Op. 34. This is a work that we know in two published versions: the well-loved Piano Quintet and a version also by the composer for two pianos that is rarely performed today. Brahms originally wrote this work for string quintet including two cellos, an unusual format because most well-known string quintets are written for an ensemble that includes two violas rather than two cellos. The manuscript for this early quintet version does not survive. However, the American cellist Terry King, using the two published versions, has carefully reconstructed the work in its original quintet format. King was a protégé of great cellist Gregor Piatigorsky and authored the leading biography of his mentor. He also was a founder of the renowned Mirecourt Trio, whose great recording of two Schumann Trios has been released by HDTT, HERE.

Bob and I were fortunate to be able to attend the John Proffitt's recording sessions in mid-January, with a crackerjack group of fantastic string players assembled by Terry King. This was very exciting for us, and we look forward to HDTT’s release of this "old but new" masterpiece.

Are there any final comments you'd like to include in this conversation?

Yes, there is one thing I really should add. As you know, there is a lot of interest in the DSD format and, as you know, the most popular DSD format at the moment is DSD256. So, today, Bob is making his original digital transfer from his source tape in DSD256. Thus, we are getting a very high quality transfer to start with.

However, as we discussed, it is very rare to find a vintage source tape that doesn't need some work. When it is feasible to release something "as is," Bob will label such a release as "Pure DSD." More often, when editing is required, Bob converts the initial DSD256 transfer to DXD (PCM 352.8kHz) for us to work on because the drawback of the DSD formats is that they do not allow for the kind of editing that I have to do to for restoration. Even in that high PCM sampling rate, we can still do all the editing and restoration required to make this sound as good as it can possibly be. Bob then releases the final result in both DSD256 and DXD, as well as a choice of lesser formats.

John, thank you very much for giving me all of this time for a conversation. I've greatly enjoyed it.

For some of the HDTT releases on which John has been involved, click this link for a listing. There is much great music to enjoy here, and the work John accomplishes with these tapes is truly magical.

Addendum: Audio samples of tape restoration problems

Given many comments in some of the online forums about the virtues of one of the commercial solutions out there for correcting wow and flutter in a tape (verging on the reverential), I decided to ask John how he went about dealing with this issue. He graciously replied, and he sent some before-and-after samples he said I could share.

John replied that a lot of the solution to managing pitch variations (which is what is caused by wow and flutter) lies in the quality of the tape heads and transport used when making the tape or later making a transfer of the tape. He said that Bob Witrak at HDTT is using a pretty special equipment set-up, with obvious great results. He takes the signal right off the tape head and feeds it to a super quality preamp, using nothing else on the tape deck itself. But, when a tape has been stretched or if your working from someone's transfer that has pitch variations in it already, then some specialized software comes into play. Of course, here you must be working in the PCM domain. He said one such piece of software is iZotope and it addresses wow and flutter works surprisingly well.

The program John works with most frequently, however, is Capstan from Celemony. He says, "Capstan can do wonders, but can also make messes--it has a real learning curve. For Capstan to work at all, the pitch has to be right to within something like a whole step. If the pitch is further off the mark, you have to do some matching initially by ear (basically just getting it into the ballpark). Then Capstan can get it a lot more right. I'll then go back thru and fix what was still wrong in a few spots by ear. Capstan is not perfect--it always leaves some error that needs to be fixed by fine-tuning with your ears. But I like the program a lot for what it will do."

He sent this sample of a live recording of a performance Beethoven's Archduke Trio that someone else had dubbed and then sent to him to see what he could do to make the tape listenable. The tape has a huge about of wow and flutter, plus tape slippage. The first 30 seconds or so is the original, the rest is John's fixed version adjusting first by ear, then applying Capstan, then fine-tuning by ear.

Example of fixing wow and flutter and tape slippage, before and after.

Another issue John deals with are vintage acetate and shellac platters with lots of scratchy surface noise. Here's an example of a very noisy acetate record. The first 45 seconds or so are the original, the fixed version follows that.

Example of a very noisy acetate record of music with Nelson Riddle, before and after.

And then there is the challenge of correcting wrong notes in a recording of a live performance. Here are two examples, before and after. These are each very short.

Two examples of correcting wrong notes from a live performance recording.

If you'd like to download these samples, I've placed them in an album for you to download HERE.

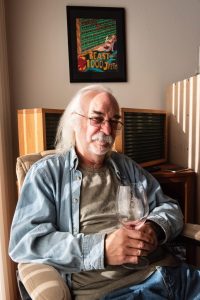

John Haley, a portrait.

John H. Haley, President

Harmony Restorations, LLC

732-533-5305

John H. Haley is an audio restoration engineer and retired attorney with a lifelong interest in both classical and popular music. He holds a Bachelors of Music degree from University of North Texas with concentration in voice and piano, and while in college he served as a professional chorister for the Dallas Civic Opera. Since 1987 he has served as a Board Member of the Bel Canto Institute (www.belcantoinst.org), an organization that teaches bel canto opera style to young singers. From 2012-2022, he served as Editor of the Sound Recording Reviews section of the ARSC Journal.

All images courtesy of HDTT or John Haley.<