My Dinner with André MFSL’s Herb Belkin

Herb Belkin (second from left), with members of the band Genesis circa 1974. Atlantic Records/ATCO

Author's Note: The following autobiographical sketch is for the purpose of setting the stage (or giving the backstory) about how a total "Mr. Nobody from Nowhere" (i.e., John Marks) managed to get his first-ever commercial recording project released by Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs, at a time when MFSL was otherwise very much occupied with Steely Dan, Frank Sinatra, Cat Stevens, Supertramp, Procol Harum, Pink Floyd, and the like.

As a child, I attended the public schools in Providence, Rhode Island. One good thing that could be said for that was that way back then, students who were achieving at their proper grade level had the option of scooting out of the classroom (during the regular school day) for free instrumental music instruction. That program started at third grade; as soon as I could, I put in for violin lessons.

Nobody in my extended family played or had played the violin. My mother had studied piano as a child. Her brother put his trombone lessons to good use as the trombone-playing vocal soloist in a World War II-era US Army "Big Band." Uncle Bill actually cut "V-Disc" 78rpm records of weepies such as "Same Old Dream." My oldest brother was a folkie with both six and 12-string guitars. But, no bowed-string instruments were to be heard.

I think my complete infatuation with the violin came about because I once glimpsed on black-and-white television a violinist playing the violin transcription of Brahms' Hungarian Dance No. 5 in f#. For all I know, it might have been Yehudi Menuhin. Regardless who it was, the striding or strutting "B-Section" double-stopped tune (daa-daa-DAAH-daa) stayed stuck in my mind.

In lessons, I paid careful attention and tried to do as I was told. I made progress, but I was truly and essentially clueless. I was more of a wind-up toy than a young musician.

Regardless of my retrospective self-criticism, I ended up as Principal Second Violin of the public school system's All-City Youth Orchestra, an orchestra consisting mostly of high school and junior-high-school students.

I believe I was the only elementary-school student. They had to find a special chair for me, because my feet did not touch the floor when I sat in one of the chairs that were in place (for the Rhode Island Philharmonic).

The first time I sat beside a conductor's podium and heard an orchestra of sixty or so members play, it imprinted me for life. Among other things, we played a student-orchestra-arrangement of a movement from Scheherazade, "The Young Prince and the Young Princess."

In parallel with all that, my Godmother's husband (Uncle Bob) gave me a reel-to-reel tape recorder he was no longer using, with which I recorded my junior-high-school chorus in lamentable drivel such as, "If We Could Talk to the Animals" from Doctor Doolittle. (That was a 1967 film musical that Rex Harrison most likely did not have to live very long after, in order to regret muchly. Sigh.) That tape recorder had a green "Magic Eye" vacuum-tube-end display for Recording Level, which I found hypnotic.

In my high-school years, I devoured both Popular Electronics and Stereo Review. To a certain extent, both were "Greek to me," but the technology for reproducing the sound of music became an enduring passion.

Despite the fact that in college, I lucked into lessons with a violin teacher who himself had been taught by a fellow student of Jascha Heifetz' in the legendary pre-Russian-Revolution St. Petersburg Conservatory Leopold Auer master class, I believed that I lacked the level of talent (and self-confidence) necessary for a professional career in music. So, I went to law school. But I never stopped loving the violin.

In the early 1980s, Arturo Delmoni came to my attention because his then girlfriend and my then girlfriend were friends, and Arturo was in residency at the summer music festival at Rhode Island College. I heard him playing chamber music, and I was so bold to ask permission for me to prospect for a record deal for him. Despite my total lack of real-world experience in that realm.

In that same time frame, my parents owned the kind of delicatessen-café that you would expect to find a couple of doors down from the Rhode Island School of Design Architecture Department building. Their customers included the couple that ran the independent record label SQN (for Sine Qua Non). I chatted them up about their possibly releasing a recording to be funded and owned by Arturo Delmoni, and licensed to them.

In due course, Sine Qua Non repudiated our letter agreement while "suggesting" new terms more favorable to them, and that was the end of that. It took a couple of years to find a new record deal, but I eventually connected with the newly founded North Star Records.

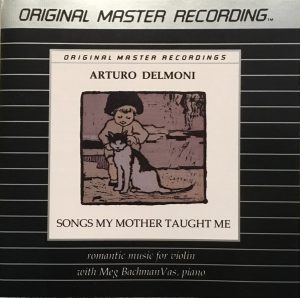

The North Star LP of Arturo's début album Songs My Mother Taught Me received wonderful reviews, and remains a hot commodity among LP collectors. However, once the Digital Audio Compact Disc achieved critical mass, North Star was not willing to make that investment, so I once again went knocking on doors. (That would have been in mid-1986.)

I started at the top! I phoned Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs (MFSL) and asked to speak to someone in Artists and Repertory. I was connected to Mike Grantham, who agreed to give Songs My Mother Taught Me a listen. I mailed out a box containing six LPs and two press kits. Grantham, upon opening the box, phoned to ask me why. I told him I wanted to avoid a slow process wherein multiple decision makers would have to pass one LP around, before there could be a consensus.

MFSL's President Herb Belkin later phoned me to congratulate me on my clever approach, and to tell me that he was willing to "take a chance on" Arturo's album. These days, the MFSL CD version of Songs My Mother Taught Me still fetches impressive money on eBay. That, despite their engineers' not quite getting David Hancock's unique EQ curve.

Herb Belkin was a fascinating guy. Herb saw an opportunity I would have been blind to. Herb took Mobile Fidelity, a record company that had first made its mark with location-live recordings (hence the name) of antique steam trains passing by, and nurtured it into the first and best-known "audiophile LP remastering" record label.

(Even though, as will be explained below, as far as I can tell, the first "audiophile LP remastering" project was actually Brad Miller's idea. But Herb Belkin picked up that ball and ran with it, in the process leveraging the Rolodex of industry contacts he had built up in his previous careers as a music-business lawyer and executive producer.)

Amateur recordist Brad Miller founded the "Mobile Fidelity" record label. Mobile Fidelity's first release (MF-1) was in March 1958, a monophonic recording of Southern Pacific railroad-train pass-bys. By September 1958, Miller had acquired an Ampex 2-channel tape recorder and two Electro-Voice microphones. Mobile Fidelity's first stereo release (MF-4) Highball received praise from High Fidelity magazine.

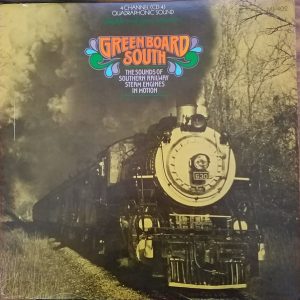

Miller continued to record steam trains into the early 1970s. Apparently, adequate sales volume was generated by ads in train-enthusiast magazines and by exhibiting at model-train events so that the game was worth the candle. Even within the steam-train genre, Brad Miller did not rest upon his technical laurels, going so far as to release steam-railroad titles such as Greenboard South (MF 402) in CD-4 Quadradisc surround sound.

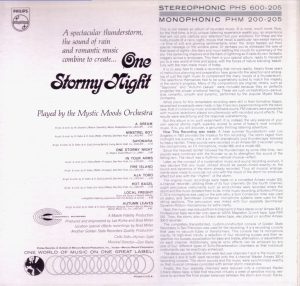

Lady Luck must have been smiling benevolently upon Brad Miller in 1965. Disc Jockey Ernie McDaniel of San Francisco radio station KFOG was inspired (by what, only the Good Lord knows) to play an easy-listening music LP on one turntable while spinning one of Miller's thunderstorm LPs (Steam Railroading Under Thundering Skies) on the other, sending both feeds to the transmitter. Listeners phoned in asking where to get that record, and a genre was born.

Working with arranger Don Ralke and a pick-up orchestra ("The Mystic Moods Orchestra"), Miller recorded a bunch of tunes, and then mixed them with environmental sounds (such as bubbling brooks) he had recorded. Miller somehow got the Philips record company to take on the title, to the eventual jubilation of all. NB, the jacket-back liner notes of the Philips LP include the credit line "A Mobile Fidelity Production" as well as an early version of the Mobile Fidelity logo.

One Stormy Night was Philips' best-selling LP title of 1966. (Can you believe that?) More than a dozen sequels followed, with distribution switching over to Warner Brothers in 1972. As the series went on, the cover art shifted from landscape or environmental photography to soft-focus images of naked couples. By the way, The Mystic Moods Orchestra's 1968 release Emotions credits Lincoln Mayorga on piano, organ, harpsichord, celesta, and clavinet.

It was a brilliant business move for Brad Miller to hook up with Philips, in view of their worldwide distribution across multiple genres, as well as the fact that there would be some overlap in musical taste between The Mystic Moods Orchestra's offerings and strong-selling, established Philips Middle-of-the-Road (MOR) artists such as Nana Mouskouri. However, one might infer that the audiophile perfectionist in Brad Miller might have chafed or rebelled at Philips' so-so, everyday-quality vinyl pressings.

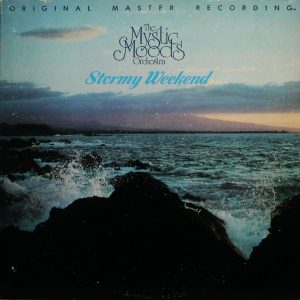

Some time around 1976, Miller retrieved The Mystic Moods Orchestra's Stormy Weekend master tapes (from 1970) and sent them off to Nippon Phonogram Co., Ltd. in Japan for "audiophile-quality" remastering and vinyl pressing. In that same general time frame, Miller changed his label's name, by adding "Sound Lab."

Stormy Weekend was Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab's catalog number MFSL 003. (Please note, projects were not necessarily released in the chronological order in which they had been remastered.)

In fact, Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab's first three LP releases were all by the The Mystic Moods Orchestra. Who knew? MFSL 001 was Emotions, and MFSL 002 was Cosmic Force; both are from 1968.

MFSL 004 was The Power and the Majesty, which was ambient thunder and train sounds. MoFi's own website's "Archive" page misidentifies this recording as a Mystic Moods Orchestra project; but it's quite obviously another steam-trains-and-bad-weather program.

If you are curious as to what came next in those earliest days, Supertramp's Crime of the Century was MFSL 005; John Klemmer's Touch was 006; Steely Dan's Katy Lied was 007; the Los Angeles Philharmonic/Zubin Mehta Star Wars & Close Encounters of the Third Kind was 008; Al Stewart's Year of the Cat was 009; and The Crusaders' Chain Reaction was 010.

Therefore, Brad Miller created both the record-business category of "make-out music with environmental sounds," and the record-business category of "audiophile-quality LP remasterings."

In a nearby (and asynchronous) Alternate Universe, that version of Brad Miller gets on the phone with that version of me… . I tell Brad not to bother re-doing the Stormy Weekend LP, because the reel-to-reel tape version sounds so wonderful that I can't imagine any LP's sounding better.

If you are a tape hobbyist, there are several Mystic Moods Orchestra reel-to-reel tapes available for not huge money on eBay. The only exception is the 7½ i.p.s. Discrete Quadraphonic tape of Love the One You're With, with asking prices from $84 to $133.

Guilty as charged, I did own a reel-to-reel tape of Stormy Weekend—not that it ever got its intended use. By the time I had a girlfriend, I wasn't bothering with tape any more, and anyway her musical tastes were along the Bob Dylan/James Taylor/Tom Rush axis, with a little Rolling Stones thrown in.

Back to reality.

In 1977, Mobile Fidelity and Herb Belkin got together. What Herb brought to the party was attitude, energy, and contacts.

Brad Miller and his partner Gary Giorgi needed new, non-Mystic Moods content, so they started cold-calling established record labels (in person, not over the telephone), seeking licenses. When they arrived, apparently unannounced, at ABC Records, Herb Belkin was willing to talk to them (he later claimed that he didn't really know why he let them into his office).

Belkin licensed to Miller and Giorgi music from the Crusaders, Joe Sample, Steely Dan, and John Klemmer, as noted above. When they came back months later with test pressings, Belkin was astounded. In due course Belkin left ABC Records to become a consultant; and by 1980, he was President of MFSL.

That came about because Belkin had been able to arrange for MFSL to get access to the original master tapes of Dark Side of the Moon. The MFSL remastering of DSOTM made its début at the 1979 CES. The response was so overwhelming that Miller and Giorgi asked Belkin to run the company for them.

Herb's previous work in various capacities at Capitol Records, Atlantic Records, ABC Records, and Westminster Gold made it possible for MFSL to remaster and reissue iconic titles from (starting at the top) the Beatles, and Frank Sinatra. All from the original master tapes. The Beatles master tapes flew First Class, beside a Mobile Fidelity executive, in lead-lined boxes.

Also: The Band; Blondie; Emmylou Harris; Al Jarreau; Little Feat; Zubin Mehta and the Los Angeles Philharmonic; Pink Floyd; Steely Dan; Cat Stevens; Al Stewart; Styx; Supertramp; and so on.

Did I mention the Rolling Stones?

So perhaps you can imagine how "over the moon" I was, that an album that was my idea (and my hard production and marketing work) was going to be a stablemate to so many world-class artists. Not to be discounted was the endorsement factor: "Hmmm… I've never heard of this artist; but if MFSL saw fit to put him out on their label, he must be good!"

MFSL also released on CD Arturo Delmoni's recording of the Franck sonata and Fauré's first violin sonata. Sales were nowhere as good as for the crowd-pleasing encore-piece album Songs My Mother… . In any event, the later JMR CD re-remasterings by Bob Ludwig really nail David Hancock's self-devised asymmetrical Noise Reduction (and tonal compensation) EQ curve, so I'd advise not paying a premium for a MFSL Arturo Delmoni CD.

At some point years ago (1997?), Herb Belkin had a family obligation back in the eastern part of the country. Herb invited my wife; Arturo; and me to dinner in Newport, Rhode Island. Herb's wife was there, too.

We met at one of the oldest restaurants in America. Herb started out by quipping that the Colonial part of Newport was like "Williamsburg with water." He was that kind of funny guy. He also ordered a magnum of a big-and-brawny red wine, probably a Cabernet, to go with salmon. So, California life had really taken to him.

Herb got along famously with Arturo. Herb grew up in Hell's Kitchen or some other NYC-area slum. He told Arturo that he had been the only-ever Jewish member of the feared (Italo-American) street gang the Golden Guineas. (HERE) Arturo was incredulous. Supposedly, the Golden Guineas were in part the inspiration for West Side Story.

Herb got a football scholarship to (IIRC) Kansas, and did well enough academically to go to law school. He then went to work for the Justice Department's Civil Rights division during the Kennedy administration, so therefore his ultimate boss was Robert F. Kennedy.

Herb told us about driving from factory to factory in the Deep South and telling the managers that they had to clean up their racist hiring practices. When they demurred, Herb would offer to take them outside and beat the tar out of them in front of everyone. Herb told us that nobody ever took him up on it.

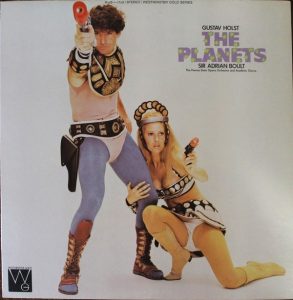

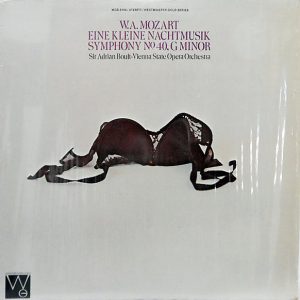

Herb then moved on to the music business, blurring the distinction between the lawyering function and the record-production function. At one time Herb worked for Westminster Gold, which was essentially a classical-reissue label, the business model of which was cheesecake-y new covers wrapping old recordings licensed on the cheap.

My choices for the Westminster Gold cheesecake LP covers that are the most egregious affronts to common decency and good taste are the "Panty Shot" cover for Also Sprach Zarathustra, and the "Bandeau Bra" cover for Eine Kleine Nachtmusik. (I assume that Sir Adrian Boult did not receive the customary LP courtesy copies.) Those LP covers show how desperate some people were, back then, to dumb down and sleaze out while trying to sell some records.

NB, I am not saying Herb Belkin himself made those art-direction choices; and perhaps it was precisely that kind of thing at Westminster Gold that made Herb want to look for greener pastures, and far away.

Someone at Westminster was well-tuned-in to the opera world. Not long after Kiri te Kanawa got to the US, Westminster Gold somehow obtained the master tapes of a crossover/Pop-and-Broadway LP that Kiri had recorded in New Zealand.

When asked about it by an interviewer for Stereo Review, her future Dame-ness was, as the Brits say, unsmiling. She said she would prefer not to talk about her early recordings. That LP (Westminster Gold WGS-8233) features "I Feel Pretty" followed by "Malagueña," with "Hava Nagila" thrown in, for some reason. You get the idea. LP copies are widely available, from 99 cents up. Impress your opera-loving friends!

At our dinner, I mentioned to Herb that Kiri had been one of my first really big Opera Crushes, and that in college I had, erm, fantasized about sharing some intimate moments with her, so to speak. In an avuncular tone, Herb advised me that expressing the wish was as close as I would ever get to the act.

I then told Herb that my daughter, at age seven, was already not only quite the music critic, but also an audio critic. She commented that The Raspberries' "Capitol Records Collectors Series" compilation CD (for which Herb was credited as Executive Producer), sounded as though it had been recorded off-the-air from an AM radio.

Executive Producer Herb brushed that off. He then offered his opinion that The Raspberries "could have been as big as Grand Funk Railroad," except for Eric Carmen's manifest characterological failings.

Well, actually, what happened was that Herb called Eric Carmen the vulgar, one-word version of the phrase "a human excretory body part." That startled my wife. Herb noticed, and immediately addressed her, apologizing for having misspoken.

Herb then raised his voice and said that what he really should have said was "The Raspberries could have been as big as Grand Funk Railroad, except for the fact that Eric Carmen is a TOTAL INTERCOURSING one-word version of ‘a human excretory body part.' " So to speak.

You could have fried an egg on Herb's loathing for Eric Carmen.

And at that moment, Herb appeared to be trying to tie his coffee spoon into a knot.

Arturo Delmoni was very impressed!

That was the only time in my life when someone, without a shred of irony, told me that a band could have been as big as Grand Funk Railroad.

I never discussed his family background with Herb, but Herb was fascinated by Russia; he was trying to develop business opportunities there. He told us of recently having had a meeting in Moscow with the (I think, by then, former) General Secretary of the Union of Soviet Composers (who had been appointed in 1948 by… Stalin).

Frankly, I was astonished. Herb Belkin knew someone who had personally known and worked for Stalin. That means that there are only two other human beings shaking hands between me… and Stalin.

Herb told us that the General Secretary had proudly told Herb that, on his watch, nobody who (directly) worked for him had been actually killed. (There had however, been many degrading's, persecutions, and retributions.)

Ever the irreverent, I smiled and said "Gee, Herb; there are members of the Kennedy family who can't say that." (Referring, of course, to Chappaquiddick.) Arturo Delmoni's shocked guffaw was my reward. Herb gave me a look.

And that was my dinner with Herb.

Someone else later told me that, as soon as Laserdiscs had come out, Herb had used his industry reputation and contacts to approach CBS/Columbia and negotiate an exclusive license for whatever back-catalog titles he chose to reissue on Laserdiscs; or, on "any optical storage medium known today, or invented during the pendency of this Agreement."

That was brilliant. It gave Herb the arguable right to play Dog in the Manger and prevent CBS from later issuing CDs. Even though Laserdiscs used analog encoding... they were an "optical" medium. Herb was able to include that language in the contract because nobody "in the record business" could ever imagine that anyone would want to re-buy on clunky, heavy 12-inch Laserdiscs music they already owned.

Then, the dawn came and the cock crowed. So to speak. It probably was just a matter of Herb's requesting master tapes to make digital copies for CD release.

So, according to the second-hand story I was told by someone who heard it directly from Herb, some people from (or representing) CBS invited Herb to dinner. They told Herb that they needed to buy out his contract; it was all just a terrible misunderstanding.

Herb demurred, asking, "What if I don't want to be bought out?"

Their reply: "Then we might have to have you killed."

Now please understand, this was right around the time that a record promoter in Miami ended up dead because he supposedly was ready to turn State's Evidence in a "Coke-Ola" (cocaine for airplay) radio scandal—as in "Payola." (A real Miami Vice plotline, that one!)

I assume that Herb wisely took the money, token or otherwise, and ran.

Herb Belkin died altogether too young, at age 62, in 2001. He truly was a larger-than-life personality whose huge impact on the record business remains under-appreciated. I am firmly convinced that Herb's tenure at Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs made countless people in the record business want to up their games in terms of sound quality. And, I miss him.

Appendix

In 1998, Herb Belkin was interviewed by the Robert Silverman who then wrote for 20th Century Guitar magazine. Silverman asked Herb for his short list of Desert Island Discs, which I reproduce here:

- The Beatles: Revolver

- The Beatles: Rubber Soul

- Yes: Close To The Edge

- Led Zeppelin: Led Zeppelin II

- Free: Free