I think it's fairly well-known in the high-end community that people tend to like what they like, and they tend to like different sounding systems. Many people like severely colored systems, but they like their kind of severely colored system and they don't like the kind of system their friend likes. Horn speaker people like horn speakers, electrostat people like electrostats, and so forth.

I still hear people debate about this, both about whether this effect actually exists, and about whether it's learned or innate. Perhaps some people are born being horn speaker people and other people are born being electrostat people.

It turns out there's an elaborate amount of research that has been done on this subject, but it mostly starts out with some work done by Rogers Edward Kirk at Ohio State, who got his doctorate for it in 1955.

Mr. Kirk took test populations of students (always plentiful subjects available on college campuses) and had them listen to records played back with wide and restricted bandwidth through a big Altec horn system. Some people liked the wideband sound, some liked the more narrow bandwidth, and it depended on the person and the material.

These students then listened to thirteen 45 minute sessions of recorded music playback over the course of six and a half weeks, with various groups listening to systems with more or less restricted bandwidth.

After all of this, students were tested again, and they turned out to be more happy with the degree of bandwidth restriction that they had been listening to for the past few weeks.

The more you listen, the more you get used to a sound and begin to accept that sound as being "correct." This is why it's so important for people to go out and listen to live acoustic music on a regular basis, music with no sound reinforcement and no playback, so they can get a sense of what the real standard is. If you lose contact with that standard, you can start going in all kinds of different directions that might be interesting but cannot be said to be realistic.

In the past 65 years a lot more work has been done to establish how people get used to sound presentations, but it all started here with a rather simple experiment to solve an important question.

Today we know a lot more, even about how reflections off the shoulders affect how we perceive sounds. We get used to that midrange notch caused by those shoulder reflections, and if we listen on headphones those headphones need to emulate that notch to sound realistic to us. This is a problem since some people are taller than others and the notches aren't in the same place for every person. Accurate reproduction of sound is a hard problem.

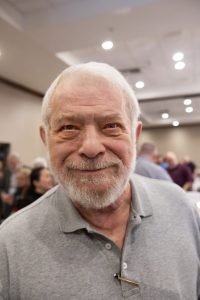

Dr. Kirk's thesis can be found at https://etd.ohiolink.edu/pg_10?0::NO:10:P10_ACCESSION_NUM:osu1485788768425055 for the curious. After graduating from Ohio State, Dr. Kirk spent three years at Baldwin Piano and Organ as a psychoacoustic engineer studying how to improve sound quality of pianos and organs as well as curious projects like improving speech intelligibility in high noise environments. In 1958 he joined the Psychology department of Baylor University where he is currently the longest serving faculty member.