Ketil Vestrum Einarsen - Photo by Dag Thrane (Used with permission)

Ketil Vestrum Einarsen was born on the north-western edge of Norway. Known primarily for playing flute with a long list of bands, including White Willow, The Opium Cartel, Jaga Jazzist, Wobbler, Pixie Ninja, and more recent collaborations in Kaukasus and Galasphere 347, he stepped into the role of leader with Weserbergland. The first album, Sehr Kosmich, Ganz Progisch, was a massive compositional undertaking that took many years to complete. The new album, Am Ende der Welt, is scheduled for an October release, and is in almost every way the antithesis to the first.

What was the original idea for Weserbergland, back before you started recording the first album?

I have played in many bands, but I felt the need to explore a different path than the bands I'd been in. I wanted to embrace ideas from the German krautrock movement, quite simply, and I needed somewhere to do it. Also, I have been working with (guitarist) Gaute Storsve for about 15 years and, for various reasons, we never finished an album. So that's also a part of the picture here.

I also wanted to embrace a tonality far away from the dark Gothic Norwegian prog and jazz. Weserbergland is very much based on classical music, when it comes to tonality, and most of the arrangements are based on choral harmonization from the 1600s.

Were all of the parts notated, then?

Not all, but a lot of it. I tried to make this into a sort of alchemical wedding between improvisation and written music. At times I edited improvisations, adapted and then harmonized them, for instance. Some solos are written note by note, like the very fast guitar lines on "Das Trinklied Vom Jammer Der Erde." But then there are parts that are completely improvised, like the guitar on "De Kunst der Fuge."

But, in general, I am a fan of the band as an organism. I wanted every part to fit in perfectly, no matter if it was written or improvised. To do so I usually work in a very dogmatic way, with clear limitations on myself or the other performers.

Can you offer some examples of the limitations you imposed?

Limitations on notes people can use in improvisations, for instance. On the flute solo-ish parts I created different scales to be used. Another dogma I used was to avoid parallel fifths / octaves / fourths as much as possible (in line with choral harmonization). This is quite hard on a a guitar, for instance, but I think it will color the music in an interesting way. A lot of prog rock uses poorly adapted techniques from classical music. I wanted to avoid this, and embraced the techniques used in classic music rather than just stealing a few chord sequences and adding a bit of harpsichord on a rock riff.

People seem to be very surprised about the theoretical approach to music I used on Sehr Kosmich, but I always remember the words of Shakira: "hips don't lie." Her point is that if the song is good, her hips will move. And if I am intrigued, on a very basic and emotional level, with a physical reaction, then I have achieved my goal.

What was the instrumentation for the first album?

That's a very long list, as every piece had 200 tracks or more. I went for a maximalist approach on it, but is still based on a seventies band I guess, with a bass of some sort on the bottom, drums, guitars, and a whole lot of synthesizers and wind instruments.

I also edited the album to the point where it is more or less impossible to play live. This choice was made because I am very fascinated by the studio as an instrument, and the computer is the new studio.

While you said that you wanted the band to be an organism, the band didn't exist as a "band" in the traditional sense, did it?

You are right. I did not even want them to meet. When seasoned musicians get together, they always seem to get into a groove based in their experiences, and that can get very boring. Many musicians do use experience to create new and incredible music, but I wanted to both make sure that people followed their own radical ideas, and I wanted them to work in a chaotic sound environment where they did not necessarily know what they were doing.

If you get a seasoned team of jazz musicians in a room, they would most likely end up making another seasoned jazz album. What if you take away their safety net? Ironically, I think that a lot of the classics in many genres were made without this safety net, and to create something new and exciting, don´t copy the music. Learn from the experience, instead, and embrace anything that will make things harder and more chaotic.

What was your strategy for the new album?

I should probably speak to a psychiatric neurologist about it. We recorded half a new album. Some of it was based on what we did live. We did two live gigs in Norway in 2017. I just did not get the "hips don't lie" feeling. I did not like it. It was good, but why would I release an album that sounded the same, but [felt] more safe? The same, and safe: Those are exactly the things I am avoiding, so I dived into the history of music and found some different things I wanted to explore.

I have always been a fan of Sonic Youth and any noisy rock, and Gaute loves it as well. I have also been a fan of renaissance polyphony for a long time. I looked at how a composer like Palestrina would create pieces of music with four parts, but the parts are equal. This is in sharp contrast to the melody-dominated homophony of the common era practice. I also wanted to use the computer in an even more radical way.

Radical in what way?

The previous album had a lot of editing, pitching, etc. And I avoided real amps and, to some extent, also real synth. I wanted to embrace an idea I have that modern music always has been in an interesting relationship with modern technology. Since I was working with music that was, in part, rooted in seventies music I wanted to make seventies music with modern equipment in the hope of coloring the sound and altering the results.

I wanted it to sound like something people could not play. And something a computer could not play. An alchemical wedding of man and machine, making it something that would not be a perfect balance between two opposites, but something else.

On Am Ende der Welt, I wanted to take this further and alter all the sound with the computer. Not just the sound, but also the form. Everything you hear on the album is based on acoustic or electro-acoustic elements, and I have sampled it. Sometimes it's long stretches that I use, or sometimes just a short sound. All sounds are messed around with, but with almost no conventional effects, like delays and other effects that can sound "vintage." I deliberately used bad pitching tools as well, to get overtones that are messed up, and interesting. I wanted the the sounds to be a result of a computer working at its very limits and, preferably, a bit beyond that. I pushed everything to the point where I met the limits of a modern DAW (Digital Audio Workstation) and I lost, slightly, control over the sounds.

You also found other ways to let go of control.

I am a huge fan of John Cage, and how he used the I Ching to create music. He made a work where he edited sound without being able to hear it. I wanted to apply chance to music, so I grabbed what I had: dice. Some elements on the album are a result of throwing dice. I assigned numbers to notes, but used notes from hexachords. They come from pre-1450 music theory, basically six note scales. I did end up tweaking it so much that it ended up as something different, but I do like to try out every possible way to find a good idea. I am also somewhat influenced by Discordianism, as well, which challenges the idea that there's a difference between order and chaos. I find that very interesting.

Lately, I have been very interested in removing the self from music. I know a lot of people's alarm would go off, as they want the opposite, but I think a lot of great art comes from this. It is just that we have very romantic (as in the era) ideals in art.

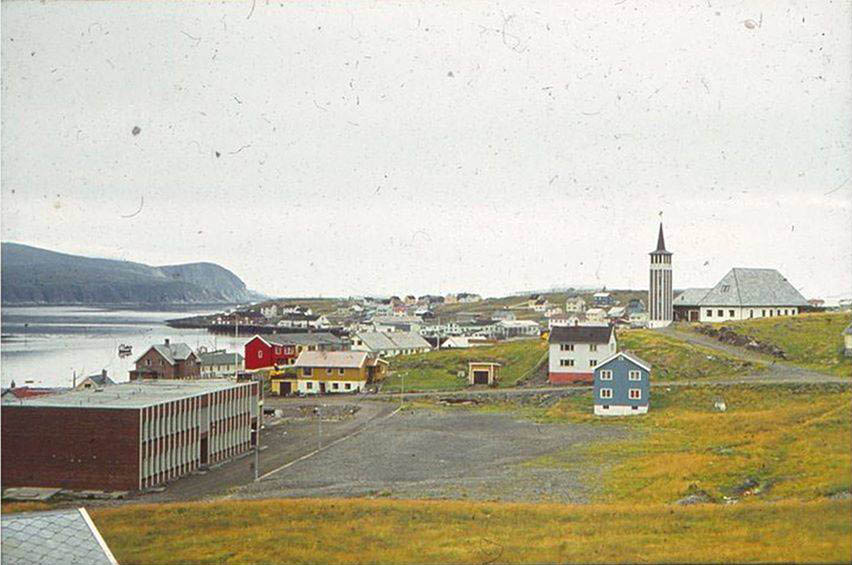

Mehamn: Am Ende der Welt - Photo by Per-Einar Einarsen (Used with permission)

I have to say that, listening to the new album, it feels completely different in every way from anything I've heard from you before. Can you speak to that?

Yes, I wanted to achieve that. Anthony Bourdain said something like, "A country's cuisine gets better by being invaded several times." Of course, imperialism is not good but it sure gave us a lot of wonderful food. Like the Vietnamese Pho, which is a French pot au feu adapted into something Vietnamese. And thus—something new is born. I purposely wanted this to happen, and chose several things, and tried to get them to work together in the hope of creating something new.

Also, "Sehr Kosmisch" is a rather positive album. I felt I needed to do the opposite this time. So it is an exploration of the concept of "end." Life has an end. Art has an end. The world has an end. I happen to be born in Mehamn, the "Alaska of Norway," a bleak landscape at the very Northwestern end of Norway. The title means "at the end of the world," and features a picture taken by my father in the seventies.

Did you start out planning to create one long track?

No, I just started with that track, a sort of philosophical and emotional approach and, before I knew it, that track was the entire album. I had planned to use the same musical strategies for more potential tracks but, after just "letting it happen," it became what it is. This is also in contrast with the first album, where almost every single detail was planned.

How did that feel, for you?

Exciting, and the music surprised me again and again. Gaute has been pushing me to do this as well, to let things breathe and not be afraid of having too little information. Also, lately, I have been thinking about ambiance or timbre. (I lack a good English word here. In Norwegian and German, the word "klang" describes this.) And how klang is the new melody. With modern music production tools, it is possible to create such intricate sounds that it becomes the melody, almost. Artists like Ben Frost or Tim Hecker are examples of that.

I come from two traditions. I studied classical music, but I have played mostly prog rock for the last 20 years. I am rather disillusioned with the genre. Being able to create something that's outside of my own craft gives me a lot of pleasure.

We've not discussed Jørgen Mathisen, who plays saxophone on the album. Can you tell me a bit about him, how he got involved in the project, and what you wanted from him?

For my 40th birthday, almost three years ago, a friend gave me concert tickets to Krokofant, an amazing band with Jørgen as the sax player. He's one of those few musicians that break out of genres. I have been lucky enough to get to know him, as we both teach at the same school. Gaute had already recruited Jan Terje from the same faculty to play keys in Weserbergland. I had heard Jørgen play solos for several minutes with circular breathing, and where he also went outside jazz scales and, instead, was embracing contemporary music. I wanted exactly that from him, and I think he delivered something very interesting.

Can you explain the process you used to create his contribution?

He played everything in one long improvised session. I was not there, so I am not 100% sure on this. I used a lot of it, but he did come in when the form on the song was done. I edited some of it. For instance, I copied a line he did (that was several minutes long), and then duplicated it four times, and then time-stretched it to different lengths.

Mattias Olsson, this time credited as Molesome, did the same. He came in and used turntables as his instrument. One of the dogmas on the album was that we could only play one instrument each. He chose turntable.

What were the technical specifications of the production?

Everything was recorded in 24-bit, with a 192kHz sampling rate. Everything was done on a laptop with a simple but very good sound card. I did not want to use a pro studio, even though microphones used in the process are good, like the Neumann u-87 and the AKG 414. But I do embrace lo-fi aesthetics. I deliberately used processes in Ableton Live that would degrade and color the sound. In ten years this will not be possible because the algorithms will improve.

You've also been releasing tracks under the moniker of WBL3. Are they part of the same project?

It's a side project of Weserbergland, and is quite simply something I do for fun. All this insane noise stuff that I am doing makes me do something quite the opposite. And I do a song or two a month in that vein. Gaute suggested that I should release the best ones. The world seems rather uninterested in it, but that's fine. We are having fun with it. Sometimes fun is just as good as the over-thinking methods I usually use.

To learn more about Weserberland's upcoming release, follow the group on Bandcamp. For vinyl addicts, their first album is available on bright orange vinyl.