"A dozen of his favorite drummers were me."

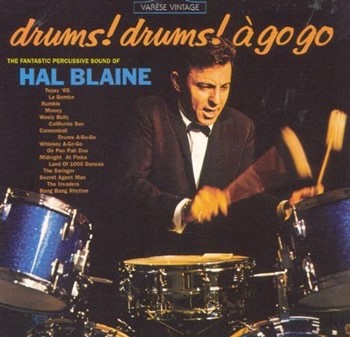

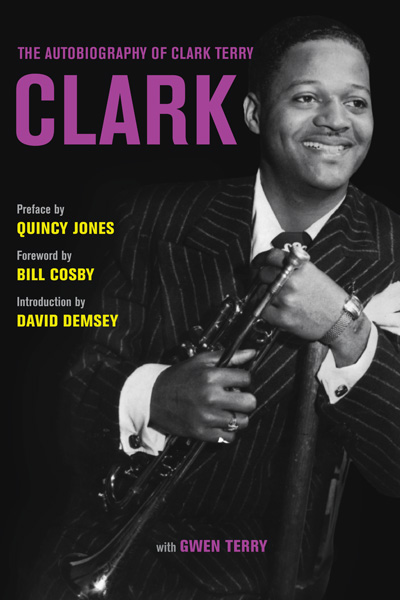

Hal Blaine

Listening and the Art of Drumming…

I remember, over the course of an extended sit down with Jim Hall back in the day, for a JazzTimes cover story, how off-putting this master guitarist found what he characterized to be a track meet mentality he sometimes encountered on the bandstand in coming of age as a jazz musician.

As dedicated musos and jazz aficionados, we often gravitate towards the most flamboyant players, the great virtuosos, particularly as regards drummers, and how we listen in a state of wonder as the likes of Jo Jones, Max Roach, Roy Haynes, Elvin Jones and Tony Williams push the envelope and inspire their bandmates to break on through to the other side…clearly all men are not created equal.

Still, when all is said and done, it isn't about who has the biggest Johnson, or who can eat the most hot dogs in ten minutes. The greatest drummers are not simply those with the most garish floor routines, nor those with the most commanding chops.

But which drummers are the best listeners.

It's about listening, sharing a collective vocabulary, remaining sensitive and open to developments in the collective conversation, responding intelligently to stimuli in the moment, telling a story…and checking your ego at the door.

When everyone is on the same page, it is a privilege and an inspiration to be part of this collective, democratic process.

As someone who has spent a goodly part of his adult life trying to attain enough technique and coordination, touch and sensitivity, to master the drum set and participate in this collective conversation, I am acutely aware of the Zen process involved in being part of an ensemble.

In the interests of full disclosure, I tend to be one of those drummers can't help himself when it comes to actively engaging the other musicians, based on how I hear the music, how I am feeling it—and how I learned to make my limitations work for me…well, more or less. It was often an awkward process as my instincts often take over, and I have to consciously restrain myself; sometimes it is best to simply sit in the pocket, and not to respond to every stimuli and provocation.

I mean, from experience, and from fucking up, I learned that while some responses might very well be mathematically correct, they are not always…appropriate.

And sometimes, if I was hearing a cymbal crash, or a fill, sometimes I came to recognize that discretion was the better part of valor. It might arbitrarily put a period on the end of the sentence, when a comma would better suit the overall aesthetic—by over-reacting, it might interrupt the flow, break the soloist's stream of thought. Then again, sometimes you want to shake them up. What's a mother to do? See what I mean?

Likewise, because I often played by myself, or one-on-one with another musician, if there was no bass player, well, I would be hearing bass lines, or chordal instruments, and since no one else was playing these missing parts, I would try and play them.

Sometimes it worked, sometimes not, but so inspired by the greatest drummers, I always endeavored to play for the benefit of the band.

It was, and remains, a process of trial and error, an exercise in existential perceptions. Learning what works, and what doesn't. What lifts our fellow musician, and what gets in the way.

Or as Dizzy Gillespie once told me (and others, surely), "It took me twenty years to figure out what notes not to play."

Or as Papa Jo Jones counseled me, "You can only play as well as the people you are playing with. I was never a player; I was always a listener—and look who I had to listen to."

From the moment I heard Cream and the Jimi Hendrix Experience, the classic Bill Evans Trio, the John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman Quartets and the classic Miles Davis Quintets of the 1950s and 1960s, that dynamic, that process; the conversational nature of their collective colloquy was captivating to me—I wanted in.

Please understand; this extended preamble is less a case of blowing my own horn, as it is of warming to my topic, to explicate key elements of the collective aesthetic, attributes which from a drummer's viewpoint might best be characterized as listening, directness, and simplicity.

As for drummers who want to dazzle you with their footwork, well, that's why on the eighth day, after He (or She) rested, God created clinics. I mean, I remember jousting with a friend, quite an exceptional drummer by the way, who took umbrage at a Bill Frisell recording where Elvin Jones often seemed quite content to sit in the pocket, playing straight time, as of someone had doped him up and forced him to dumb it down at gunpoint—as if Elvin Jones was ever unready, unwilling or unable to play 1-2-3-4, 2-2-3-4 when that is what the music fucking called for.

And yet, Elvin still managed to put a delicious, personal spin on the most simple of orchestrations…I mean, listen to the little vaudevillian, shaking his straw hat, SnagglePuss/Exit Stage Right, "So Long Everybody" flourishes Elvin puts on the outro at the end of each chorus cycle on this trio recording of a Stephen Foster tune with Bill Frisell.

Not just a virtuoso drummer, but a virtuoso listener.

I mean, Ellington's drummer of the mid-50s to the mid-60s, Sam Woodyard, could lay in the cut, like lockdown at Rikers Island, and play so simply and directly, with minimal flourishes or ornamentation, and yet when it was time to up the ante, well now, it would appear he had ample horsepower under the hood.

Finally, I recall seeing the Modern Jazz Quartet live, my one and only such experience, a set at The Blue Note in NYC, and Connie Kay was so elegant, so focused, so melodic, such an incredible team player and engaged listener, it simply blew my mind. After the set, I made a bee-line for the stage, introduced myself and exulted as to how "...if I ever tried to even play eight bars so heroically chill, purposefully to the point, and in the pocket, my liver would explode." Connie laughed and clearly he took it as it was meant—an acknowledgement of his mastery.

The point being, that there is more than one way to skin a cat.

And while as drummers and listeners, we surely love the most flamboyant virtuosos, often he who plays less, says more.

Which brings us to one of the preeminent listeners in the history of American music—a virtuoso of form and as such, one of the greatest drummers who ever lived.

Hal Blaine, Playing for the benefit of the band: Hal Blaine has left the building.

Well, not really.

Hal Blaine isn't gone…how could he be?

He ain't gone…he's only dead.

You dig, because whether you know it or not, ubiquity, thy name is Hal Blaine—a giant of American Music and an omnipresent spirit in the collective unconscious of our cultural heritage.

I mean, once you start ticking off the #1 records this Mandarin Of The Studios played on as a member in good standing of that cabal of legendary session giants the drummer dubbed the Wrecking Crew, well, it starts to get a tad ridiculous.

Born Harold Simon Belsky to Eastern European immigrants on February 5, 1929, Blaine grew up in Holyoke, Massachusetts, before relocating to the West Coast with his family in 1943.

Harold studied drums with Roy Knapp, who also mentored Gene Krupa, and while cutting his teeth on jazz, Belsky played in every imaginable working musician's setting, fine-tuning his skills as a sight reader by playing strip clubs and touring with singers and big bands, before transitioning into rock music and studio work in the 1950s and 1960s.

As such, Hal Blaine became part of the de facto rhythm section on countless recordings sessions for producer Phil Spector, contributing to a dizzying number of hit records, most famously on The Ronettes' iconic 1963 release "Be My Baby" and a gaggle of other recordings as the rhythmic ringleader of those studio mandarins who collectively became known as The Wrecking Crew—often ghosting for the likes of The Beach Boys, The Byrds and The Monkees, augmenting their vocals with a sense of groove and harmonic command that spelled…H-I-T-S.

Hits, hits and more hits.

Blaine was featured on something like 150 Top Ten Hits and 40 Number One hits. Ha's command of any and all genres was remarkable, allowing him to vector effortlessly from the likes of Elvis and Frank Sinatra, to Simon & Garfunkel and The Carpenters, the Fifth Dimension and The Tijuana Brass…

And what made Hal Blaine so great?

He was a virtuoso listener, with a brilliant ear for the tuning and melodic possibilities of the drums and cymbals—like he was French kissing the microphones.

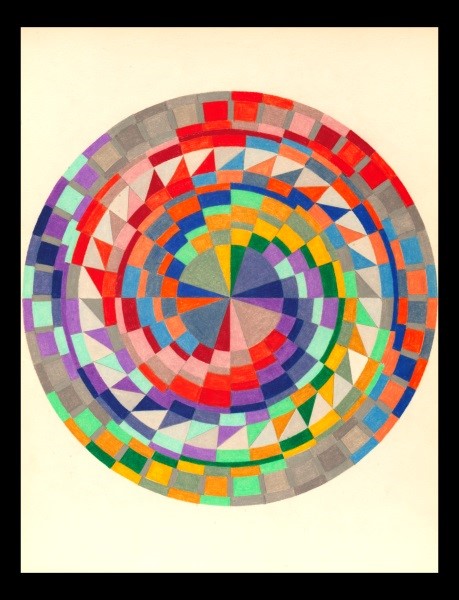

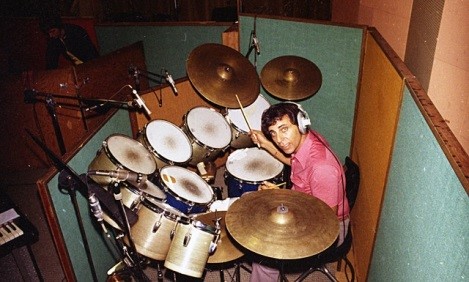

Blaine used to tune a standard drum kit to the melody of Gershwin's "I Got Rhythm" and over time, he famously developed a huge multi-TomTom kit that featured eight meticulously tuned toms, allowing him to play melodic/diatonic patterns, and thus, to speak…to sing on the drums, italicizing the predominant melodic strains while echoing and answering the vocals in a coherent manner, making his fills and transitions ever more musical and engaging.

Hal had an innate sense of form, and a lovely notion of how to tie everything into a neat, coherent package—to make everyone else in the band sound better, to shine the spotlight on the vocals, while maintaining a perfect balance of tension and release.

But ultimately, Blaine possessed an ineffable quality that is neither a matter of tuning nor of technique.

As a drummer, Blaine had exquisite…TASTE. He could generate tension and excitement, or slip on his cloak of invisibility and pare things down to the bare essentials that functioned totally in the service of the music.

This did not simply reflect musical talent, but a genuine sense of spiritual empathy—a gift for imparting collective joy, thus bringing people together in a tangible manner. Not unlike the function of the bass (let alone the bass player); that is to say, bass, not merely a reflection of the instrument itself, nor the lowest tones, but those notes without which none of the other notes would cohere or make any damn sense.

Again, playing the drums may be the most existential process in all of music. At the risk of repeating myself, as a drummer, early on, one learns that while something might be mathematically correct, that does not necessarily make it...appropriate.

Max Roach once told me about an early recording session with Charlie Parker, and how the saxophonist handed out charts to everyone, but nothing for Max.

"Hey Bird," Max queried, "Where's my part?"

Bird brushed him off thusly: "Aw, Max, you know what to do."

Dig that.

And that, my friends, encapsulates the enduring greatness of Hal Blaine because whether on the bandstand or in the studio, there's generally a part for everyone—save the drummer. Oh, perhaps there's a rough an outline—something indicating the odd accents or where there's a suggestion as to how the drummer might interpolate a break or a fill.

Because nobody knows how to tell the drummer what they want—but everyone knows when it is wrong.

Nobody ever had to tell Hal Blaine what his part was, and in scrutinizing the immense expanse of his recorded legacy, his signature writ large on the vast expanse of American popular music (though often written with invisible ink), it is no conceit to mention him in the same breath as a Mozart or, more appropriately, the great Motown bassist James Jamerson, where one cannot conceive of one note more or one note less—it was all there and it all worked.

Hal Blaine played it like he wrote it.

And it got to the point where if producers could not get Hal Blaine, they would literally book one of his drum sets—as if that would confer some aspect of Blaine's bankable magic mojo.

Few drummers have ever played for the benefit of the band with a sense of what best served the music, quite like Hal Blaine.

God bless and God's speed, Brother Belsky.