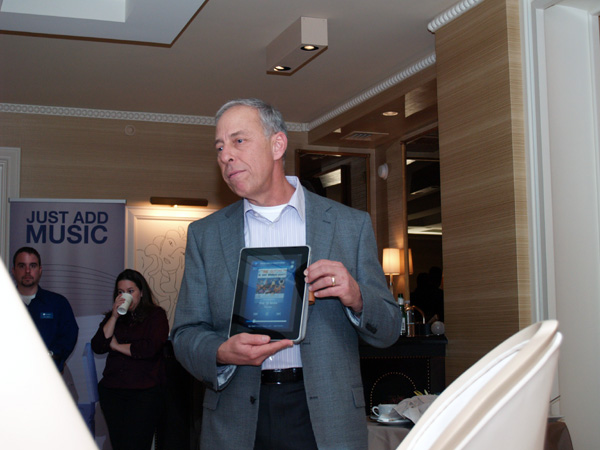

On Friday, after T.H.E. Show in Newport Beach—actually in Irvine—California, I went to dinner with PS Audio's Paul McGowan and company: Arnie Nudell, Bill Leebens, Scott Schroeder and Paul's son, Scott. Ostensibly, I was there to talk about something Paul wants to do that will probably involve me. But the talk took an interesting direction.

This was the show at which PS Audio introduced the first pair of BHK Signature monos, 300-watt hybrid amps, using a tubed initial-gain stage and MOSFETs in the amplification stage, and named for their designer, the legendary Bascom H. King; part of a new series from PS featuring non-in-house designers, including their DirectStream DAC. (The stereo 250-watt BHK Signature was introduced a few weeks earlier in Munich). On first hearing, with Legacy speakers, they are appropriately revealing of what you feed into them. Neither big nor little, wet nor dry; exactly what one would want. Arnie played a violin recording for me that I dragged Neil Gader in to hear because of the size of the violin.

I don't want to get into reporting exactly what was said at the dinner, but the thrust of it had to do with the choices that went into making the BHK. Now, I've used dead-simple amps for 23 years: the Brown Electronic Labs 200-watt 1001. Richard Brown, the man behind them, always said, "You want good sound? Or you want to pay for metal-work?" Obviously, I opted not to pay for metal-work. So this is a subject that interests me greatly, particularly as the BHK amps are a little bit fancier than the BELs.

But the particular way the conversation went was very informative. It had to do with the circuit-design choices made by King, who was recommended to Paul by Arnie, and the materials choices made by the whole design team. Bascom has designed amps for a number of companies over the last 40 years, including Infinity, GAS, Constellation Audio, Marantz, and Conrad Johnson. In particular, the design was compared to an amp he had done for one of these companies that used a similar circuit. I found it very interesting, to say the least, that a picture emerged of two very opposed design philosophies—one might call them bottom-up and top-down. The approach Paul and his team take is from the foundations up: it was described at the dinner as cost-plus. All of the components that make up the amplifier: parts, labor, and overhead, are added up and a multiplier is applied to come up with what they determine to be a fair price. I have to admit, having not really thought about it, that I assumed this was the way everyone did business. But the amp that was cited for comparison, of similar design, used a top-down approach. This is really very different: a price is set first. How much one might be willing to pay for the component is first determined, and regardless of what goes into the piece, this is the price. In other words choosing a category of price and stature first, figuring out a fitting metal sculpture, worthy of the genre, second. Then the work begins, choosing an enclosure commensurate with the category, and filling it with something that sounds as one would expect. That's very different than cost-plus pricing where the price reflects what goes in to what you're buying. You can see, counter-intuitively, why it would be very successful: particularly when there is a dealer network involved, potentially a LOT of money might change hands.

It's an old battle; shortly after I bought my last preamp, the EAR G88, which had a retail price of $11,000 in 1992, designer Tim deParavacini raised the price to $20,000 in an attempt to kill the market for something he found a royal pain to build. Instead, as I recall, he got six orders from Asia almost immediately. It's an established fact of our "hobby": some people like to pay a lot for it. To these folks, the price seems to denote the quality.

That's not to say that top-down components aren't as good, or wonderful. Sometimes they might be; often they are. And if one has "more money than god", to put it colloquially, why not spend it on sculpture—whether as pure art or as a piece of electronics? (A few summers ago on a retreat in the redwoods I saw a truly compelling piece of metal sculpture and I thought long and hard about selling my Neumann M-49s microphones to get it. Certainly my eyes would have gotten more use out of it in the years since then than my ears have out of the M-49s.)

McGowan's website says that the BHK Signature is "one of the best amplifiers in the world". It might well be; I haven't heard it compared to any other. And I've only briefly heard the amplifier that it was compared to in the discussion, in an entirely different system at a show. The whole set-up sounded very good. That's not what this is about—it's about value, and the perception of value. It's about what we choose to pay for. That other amp—it looks real good. I'd even go so far as saying it looks nicer than the PS does, like a piece of subtle sculpture. Would I want to pay three or four times as much for that sculptural quality? As opposed to saving my money and buying a piece of actual sculpture? Like I said, there are people who have "more money than god". They have to spend it on something.