Finishing graduate study at Stanford, 1970-72, I was Director of Admissions at the The Athenian School, a small and innovative prep school on Mt. Diablo in the Bay Area. It was funded by the Ford Foundation as a tribute to Dyke Brown, its longtime Vice President, a going away present supporting educational objectives he'd championed over many years to augment the intellectual rigor of secondary school education. The faculty was remarkable: Carmen DaVivi, a strong painter who kept things fun and loose; my Princeton classmate, Dave Oliver, was a sober advocate for high academic standards, as was Louis Knight who went on to teach at the Thatcher School the year before I went to Cornell. Robert Hughes, the Assistant Conductor of the Oakland Symphony, taught music. Munzer Afifi was a colorful math teacher from Lebanon's exotic crossroad. Gail Bakutis went off to become the Director of the only English-speaking theatre company in Paris before, alongside her tragic husband, she moved to the ocean's edge near Pokai Bay on Oahu. In my campus home's garage, which I converted to an open platform seminar room, I taught a year-long senior course in Greek and Renaissance Thought whose students graduated to Yale, Stanford, Reed and Harvard—like Phil Anglim, who played the first role on television as "the elephant man" for the BBC.

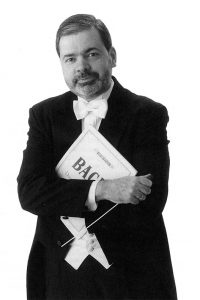

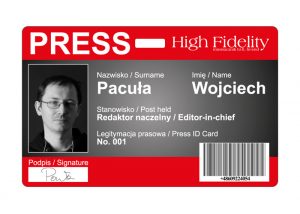

Jennifer Jones, actress (photograph courtesy of CNN)

It was a special place: at its core visionary but, in those years, under-siege by Vietnam era cultural turmoil. Two student applicants stood out. The first was the arrival on campus, in a bright yellow chauffeured Rolls Royce, of actress Jennifer Jones and daughter, Jennifer Selznick, whose father was the immortal Hollywood eminence, David O. Selznick.

Jennifer Jones and David Selznik (photograph courtesy of The Telegraph)

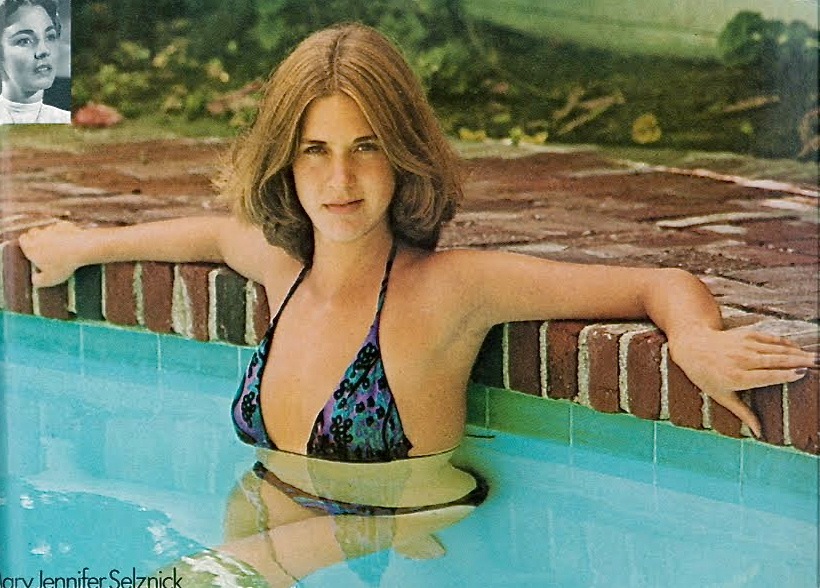

Several elements swirled through young Jennifer's time at Athenian. She was perpetually on the brink of suicide. I was her chosen amanuensis. In addition, she performed daily Tai Chi exercises directly in front of my house that literally opened onto the full height of Mt. Diablo. She was, one might say, always in sight each morning. One could not miss her. Ignoring her Chaplinesque pleas for continuous attention was impossible.

One of my final actions as admissions guru was to call her mother, an imperious aging actress who was married to billionaire art collector, Norton Simon. I had the unhappy duty of informing her that young Jennifer was a basket case who was on a direct path to suicide. I can say without equivocation that the blistering attack I received on the phone that day was an ultimate experience of a new hole bored in my derriere. Nothing before or since has lifted to the negative flamboyance and emotional darkness of that performance. I endured its full wrath galvanized by its soaring rage, astonished by its instantaneous eruption. I remember a brief moment's pause when she finished. My amazed goodbye intended a degree of frazzled irony. I'm sure I'd already lost whatever footprint that reciprocation claimed.

Mary Jennifer Selznik, 1954-1976 (photograph courtesy of Find A Grave, sadly)

That summer, my duties on Mt. Diablo concluded, I taught two courses at UCLA: one a hundred-plus student lecture course on 20th Century American Poetry that held four nubile seductresses who starred on the national television show, THE GOLD DIGGERS. Each sat in the front row. Young instructors do not benefit by such visual harassment. The other course was a graduate seminar in Critical Theory. Young Jennifer knew I was at UCLA and found a way to invite me to her mother's Malibu mansion. When I arrived the grand tour of its palatial pulchritude was in order. Jennifer was a sadly broken girl of eighteen, profoundly miserable with ineradicable depression. With something that resembled defeated pride, she showed me her Athenian graduation present... a Picasso painting from his blue period, a canvas I recognized from my modern art course at Princeton with John Turner. Feckless, I mumbled my admiration for her windfall's bounty. A pall came over her spectacular private room. She confessed that the gift felt like a bribe from her parents so she'd remain peacefully out of reach. That black kite carried a long tail. The list of diminutions stretched on. She was always chauffeured everywhere. Flown on private jets to Europe. Given carte blanch on Rodeo Drive. Supported in any wish or whim. The one thing she did not receive was assurance of self-worth. She was extraordinarily calm and mordant in her litany of endless benefits and emoluments. She was also bitter with understated resignation to a life of unrelieved resentment for emotional neglect. In my fourth year at Cornell, as founding dean of Cornell's Freshman College and, also, Coordinator of the Ivy League Writing Consortium (which included MIT, Chicago and Stanford), Jennifer leapt from a west Hollywood hotel's 22nd floor.

The stunning deaths of Carrie Fisher and her mother, Debbie Reynolds, two days ago now plunges recall to somber revery. My earnest attempt to affirmatively mentor Jennifer Jones' daughter succeeded like rain off a duck's feathers. The month that young Jennifer graduated, Debbie Reynolds' flippant self-confidence appeared in my second floor view of Diablo's grandeur. Once again I was not adequately prepared. The old adage George W. Bush never got right—fool me once, shame on you; twice, shame on me—found its mark on me.

I was not so much fooled as defeated in advance by Jennifer Jones' imperial self-assertion. With the pugnacious Debbie, far and wide regaled as the adorably cute neighbor or girl friend everyone wished for, I was put off (immediately irritated) by her failure to live up to any sort of advance notice. We sat down for lunch. Debbie held forth as if her scolding Nurse Ratchet was instantly liberated. Not a moment revealed charm or mature relaxation. No hope's poised anticipation penetrated her monologue. For an hour or so, her daughter, sixteen year old Carrie Fisher, sat like a mummy swirling cold soup. I introduced Carrie to several students who took her for a campus tour. Debbie and I retreated to my upstairs crow's nest. Was she to understand, she demanded, that Carrie was admitted and they could now leave? Since Carrie's paper work as such had arrived in my hands well in advance of this mere formality, surely the decision to admit her daughter was a fait accompli. Tone deaf and heedless of her charmless demeanor, the perky witch assumed her demand was obviously accomplished before their arrival. I told her (a flat out lie) that the Headmaster was in New York, to return the following week. Decisions to admit students, without exception, were shared with him.

Carrie Fischer and Debbie Reynolds (photograph courtesy of People magazine)

That disappointment triggered a small earthquake of incredulity, outrage, and pique. In short, she threatened to deny us the good luck of her daughter's glory (somewhat flawed, she previously noted) and was, therefore, prepared to have her driver bring the Bentley around to squire them back to the Oakland airport. This bloated turn invoked my lecture from the ponderous Jennifer Jones the week before. It was not the same person, here reincarnated, again troubling my youthful dedication to impeccable professional courtesy. Debbie Reynolds' style of insult was more direct than Jennifer Jones'... whose divine satanic wrath left me listing leeward upon sitting down. Quicker, her weapon close, it cost Debbie no time or thought to open her purse and look within. This was a well-rehearsed routine perfected by decades of self-pity aroused by superior arrogance. She had the same motive as her starlit colleague. It was, however, carved from different emotional excess. I'd been the voluntary fool who knocked on a famous woman's burly gate and earned an idiot's reward for the effort. Who doesn't enjoy insults from those who wash laundry on Mount Parnassus? Odysseus handled his deprecation just right, faking out the Cyclops. Less than five feet from my unhappy witness, the Grand Dame of Public Loss (exhibit A in a pantheon of secular victims) briskly moved to indulge her wounded pride. Looking in her purse, knife or revolver, whatever she pretended to find there, the ensuing discourse implied that vigilant Hollywood compatriots stood nearby, perhaps a notorious lawyer on retainer, maybe a yet more sinister affiliation was ready to step in. Her allusion carried a kind of muffled delight that, despite disappointment, she enjoyed seeing how such "misunderstanding" or "unfortunate error" would work out if she decided to reach deep for her covert weapon. No matter what, if the school did not take her problematic daughter off her hands, its paws would soon feel sharp consequences. I was the nugatory dud who'd soon learn the results of inconsiderate treatment of this dysfunctional duo, Debbie and Carrie.

Truly, there are occasions that, in retrospect, one takes pleasure re-plotting with dark Dostoyevskean contrivance. And yet, the circumstance as it happened and I now see it play out long ago, held a gentle resonance that no one (most of all me) could predict. With menace at the corners of her wry snarl tossed across my desk, Ms. Reynolds' demand repeated itself, more modest, more threatening. What conclusion, she wondered philosophically to herself, did I prefer? A quiet rational agreement that Carrie would join our ranks? Or the incomprehensible discord of things awry she had no control of, but promised would occur if this brief bivouac terminated on the noir vibe so redolently regnant? I believe it dawned on me right then that this woman was desperate. She hugely wanted her daughter out and off, as far distant as possible to give them both relief. I'm not sure if I felt a twinge of sympathy. Maybe so. I can't recall. But the landscape she brought with her was cratered with despair and toxic smiles.

Stylistic differences notwithstanding, Debbie's urgency—antithetical to her equally- lionized colleague's bland disappearance from the campus and her daughter's need (an absence that, in its wicked disburdenment, asserted unthwarted staccato abuse)—was, in truth, a barely contained hysterical plea to cooperate. Or else. If a plea ever masked itself in the guise of simultaneously overt and covert insistence, this was it. That sunny day in April 1972 I merely wanted to escort this joyless icon to the esplanade's stairs with a loving nudge of polite sayonara. However, I did not want to burden Dyke Brown. He trusted me. I preferred that trust to her defeated victory's imagined triumph.

What took place in the flick of a clipped toe nail surprised us both. I have no idea why I proclaimed that, in the absence of our head honcho, a decision to reward Carrie with admission could happen within two short hours of time well-invested. This intrigued wary skepticism. What on earth, she seethed, could that be? Well, I suggested with delighted malice, admission "on contingency of extraneous successful documentation" was a seldom employed option available. Which meant what, she snarled. It posed, I replied, the intervention of a quickly crafted 500 word statement from Carrie upon completion of her institutional tour.

If cell phone cameras had been available in 1972, I'd want mine to have snapped Debbie Reynolds' glowering effigy. Sitting before her simpering cartoon's unabated smoldering, I saw that she was smarter than many may have acknowledged. She was no dunce or dummy, unlike the other shoe that dropped, fooling my stupid youthful belief in honest discourse. I was learning on the fly after a previous crash that alerted self-preservation's profound conscience. All in an instant's startled instinct. She realized I offered a bargain that avoided an unwanted stand off. Reluctantly, surprisingly in retreat, she agreed. When Carrie returned from her rounds, she scrawled several pages of acute self-reflection. Whatever she said, it was marked by clarity and arch self-definition. In a phrase, Carrie was a compelling writer. She demonstrated not merely verbal presence, but narrative command. I was surprised absolutely, maybe stunned. While her mother fumed with barely muffled anger and anxiety in the rented Bentley, I interviewed Carrie.

She was armed with sharp observations and discursive swerves. Interviews were de rigeur. This one had the beguiling appeal of a budding storyteller. One graphic detail of her essay stalked our conversation. Carrie could not stand her mother. She found her controlling, vengeful, arrogant and cold.

My sympathy, goaded by her intelligently seductive writing off-the-cuff, was now complete. I doubt that I responded verbally in any memorable way to Carrie's deep desire to get as far from her mom as possible. I do recall that the decision to admit this truly interesting, highly-talented young woman (far from merely a "girl") was now an ineradicable conclusion. What began that afternoon as passive aggressions give and take—defined by my momentary discombobulation in the presence of Debbie Reynolds' overt aggression—morphed into a startling discovery of youthful talents ferocious raw motivation to gain room for its full force.

Jennifer Jones' ream-out diatribe was, for me, truly one from the ages never again repeated. I was fooled by my belief that, just maybe, I might help her sweet confused kid fend off inner demons. That set back still warm, Debbie Reynolds' smoldering complexity, boldly unfurled, led my perverse jacquerie in turn to fool her: a moment's detour to a back door entry for what, in fact, was a foregone conclusion. I, with adamant derangement, was also tricked... discovering an adolescent talent with genuine promise. Who could know then how promising such hidden inner depth could be? Carrie Fisher (Eddie Fisher's daughter) did not need to be as engagingly verbal and imaginatively endowed to be admitted. Her voracious candor added to her unalterable appeal.

When her chastened mother joined us to learn the news derived from this spontaneous verification's extraneous fragment, neither displayed joy, happiness or satisfaction. Pompous to the end, Debby portrayed righteous vindication. Carrie looked at me with what I took to be pleading relief, as if hoping to remain on campus without waiting for fall's matriculation to claim her victorious distance from Malibu's sequestration.