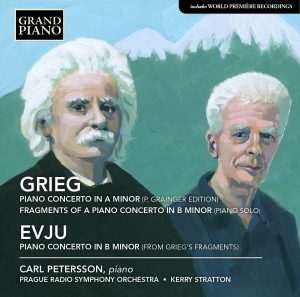

GRIEG: Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 (rev. Grieg and Grainger)*; Piano Concerto in B minor (fragments); EVJU: Piano Concerto in B minor (on fragments by Grieg)*; GRIEG: Two Songs (trans. Evju for solo piano).

Carl Petersson, piano; *Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra/Kerry Stratton

Grand Piano GP 689. TT: 56.35

Downloads: prestoclassical.co.uk (320-kbps mp3, FLAC); emusic.com (320-kbps mp3); amazon.com (mp3 or streaming); itunes.apple.com; songxpk.info (Evju Scherzo only)

The primary interest here for most listeners will be the Norwegian composer Helge Evju's B minor concerto, based on themes by Edvard Grieg, who'd apparently sketched out a few themes for a second piano concerto in 1883 before abandoning the project. The fragments were not discovered until the twentieth century; in 1997, the Oslo Grieg Society invited Evju "to create a new concert piece using the pre-existing fragments, or elements from them."

The result is not, nor can it be, "the Grieg second piano concerto," or even a performing edition thereof—indeed, Evju makes no such claims for it. Too much original, conjectural composition was required to flesh out less than three minutes' worth of music into a twenty-two minute score. It's more appropriately considered an hommage, or a concerto "after Grieg"—the sort of thing he might have written as a contemporary of, say, Rachmaninov.

Nor is it a bad piece, in its deliberately retrograde way. It's cast in five short movements, with a solo cadenza, two-minutes-and-change in duration, standing as the fourth. Evju's contributions have incorporated, consciously or otherwise, stylistic traits of other Romantic composers. A passage of dancing piano writing over quick woodwind squibs in the first movement suggests a similar passage in the Finale of Tchaikovsky's First Piano Concerto; the Adagio's string-based opening, and the setup and final tutti of the Finale, are straight out of Rachmaninov. (The supposed resemblance of one theme to Leoncavallo's Vesti la giubba, however, cited by Evju in the booklet, certainly eluded me.) Other passages—the lilting 6/8 Scherzo with its lyrical, ruminative cadenza, and the Finale in the same meter with its heartier, more vigorous swing—are striking and original. And, while the understated, bittersweet opening theme stands at the opposite pole from the A minor's rhetorical flourish, there are a number of modal themes with folk-music contours such as Grieg favored.

Carl Petersson's virtuosic playing makes a strong case for the score, especially as seconded by Kerry Stratton's firm, stylish leadership—the woodwind obbligatos in the Adagio's recap are sensitively shaped. I was less taken by the pianist's take on the familiar A minor concerto, however. This is certainly not due to any lack of either expertise or flair: the first movement's descending double thirds come off dazzlingly, while the runs in the cadenza offer both musical shaping and lapidary finesse.

The reservations arise, rather, over Petterson's handling of tempo. The artists use the version of the score prepared by Percy Grainger in collaboration with Grieg, which apparently incorporates a number of revised, tightened tempo indications. (The copious markings included in the track listings for both concerti suggest program scores on the scale of War and Peace.) And, in the booklet, annotator Anthony Short remarks on "the total absence of excessive rubato" in Grieg's own recordings.

The soloist apparently takes all this, especially in the first movement, to mean that there can't be any "give" in the musical line. Can we really not spare a little time for atmosphere at the start of the development, for example? His version of rubato, reversing the usual pattern, favors an immediate forward surge followed by relaxation, which is fine, except when he forgets about the relaxation. Time and again, conductor Stratton will project an orchestral passage expressively and with purpose, only for Petersson to barge in abruptly at a faster pace; the result simply sounds impatient, even boorish. In fairness, he does let up in a reposeful Adagio, and the score's final climactic tutti is blessedly free of unearned grandiloquence.

Once again, unfortunately, an interesting production has been spoiled for me by aggressive engineering. At a volume setting that allows you to savor all the music's vivid colors, the trumpets and high reeds turn harsh and blasty, not only at the climaxes, but in the crescendos leading up to them. The high violins suffer less, but they, too, harden unpleasantly. I've had this complaint about so many releases lately that I'd begun to think my hearing might have gone haywire, until I remembered that perception of high frequencies was supposed to deteriorate, not sharpen, with age. In any event, particularly in the B minor concerto, I found myself cringing at peak moments.

Evju's piano-solo transcriptions of two Grieg songs are impressively done, and the sound in these is fine. Petersson's surging rubatos in With a Water Lily seem extreme compared with what a singer might actually do, though that isn't necessarily illegal in a concert rendering. He's more authentically ruminative in A Dream, weaving full-bodied sonorities from the fluent passagework.

Stephen Francis Vasta is a New York-based conductor, coach, and journalist.